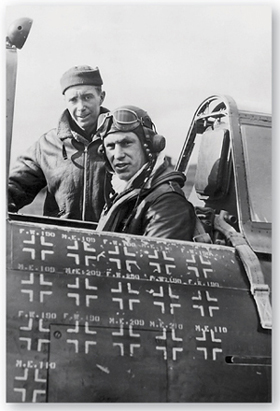

Robert S. Johnson, one of the leading 56th Fighter Group aces, is credited today with twenty-seven aerial victories. He shot down eight German fighters in one month during the intense air battles over Germany in the spring of 1944. For a time, he was the Eighth Air Force’s leading fighter ace.

“The strained manpower situation in units operating in defense of the Reich demands urgently the further bringing up of experienced flying personnel from other arms of the service . . . for the maintenance of the fighter arm.”—–Adolf Galland, General of the Fighters, March 1944

SINCE NOVEMBER 1943, the RAF had waged a singular campaign against the German capital. In what became known as the “The Battle of Berlin,” the British launched sixteen maximum effort raids on the city through the winter of 1943–1944. Bomber Harris declared, “It may cost us a thousand bombers, but it will cost Germany the war.”

The versatile DeHaviland Mosquito played a significant role in Bomber Command’s operations in 1943 and 1944. Some flew nocturnal hunting missions as night fighters, prowling the flanks of the bomber stream to pick off German Bf-110s and Me-410s. Other Mossies flew ahead of the Lancasters and Halifaxes to mark the target area in the pathfinder role.

By this point in the war, Bomber Command had come up the night attack learning curve. Using early electronic countermeasures techniques, such as “window” or chaff to spoof German radars, the British had on occasion been able to throw the Luftwaffe off its game and hit targets without significant interception. New navigation aids helped considerably, and the number of aircraft that actually bombed the primary target steadily increased through 1943 and 1944. Radar became a staple for both the heavy bombers and the night fighters sent out to protect them. And by mid-1943, a radio transponder system known as “Oboe” provided decent poor weather guidance to a target area. Oboe used two stations back in England that homed in on a radio beacon carried by a pathfinder DeHaviland Mosquito. The stations would pinpoint the pathfinder’s location and guide it to the target area. Once in the right place, the Mossies would release parachute flares to mark the area. Further pathfinders would then drop incendiary bombs on the flares, creating a conflagration in the target area that served as the aim point for the rest of the bomber stream. With Oboe, the heavies could sometimes strike their targets with nearly the same level of accuracy that the Norden bombsight possessed. It was used extensively in the Ruhr Valley, but it could not operate all the way to Berlin due to the curvature of the earth. For such missions, Bomber Command relied on the H2S radar system carried by its Lancasters and Halifaxes.

The Battle of Berlin began in November 1943 at a time when Bomber Command had finally made the jump from a twin-engine dominated force to one far more capable, thanks to the massive influx of Halifaxes and Lancasters. Nevertheless, Berlin was the most heavily defended target in the world at that time, and Bomber Command lost five hundred aircraft trying to break the German people’s morale with the destruction sown on their city.

By late 1943, the Wellington was being phased out of front line service as more Halifaxes and Lancasters rolled off the production line. The enormous amount of material, treasure, and humanity Great Britain poured into Bomber Command finally began to pay dividends. By the time the Battle of Berlin began, the vast majority of the squadrons committed to it flew Lancasters. Eventually, Lanc crews carried out just over seven thousand sorties over the Nazi capital out of about nine thousand total during the campaign.

The first night’s attacks resulted in only nine bombers lost. Encouraged, Bomber Command struck again a few nights later. Between missions to Berlin, the RAF continued hitting cities in the Ruhr and elsewhere throughout Germany. The low loss rate did not hold. As the campaign wore on, Luftwaffe night fighters—including now the deadly effective Heinkel 219 “Owl”—found their way into bomber stream and took a devastating toll. From November 18 until the end of March, the campaign cost the RAF over a thousand aircraft (five hundred alone on the Berlin raids).

The grinding loss rate appalled the crews, who felt as if they were being thrown away for little purpose. Morale plummeted. One squadron alone suffered over 100 percent losses in three months. On some missions, the RAF senior leadership questioned the resolve of the crews in pressing home their attacks on Berlin. After the campaign, one group commander, Air Vice Marshal Bennett, summed up the situation: “There can be no doubt that a very large number of crews failed to carry out their attacks during the Battle of Berlin in their customary determined manner.”

While losing over 1,000 bombers and another 1,600 damaged (plus 3,700 aircrew), Bomber Command inflicted extensive damage on Berlin. By the end of the campaign in March 1944, almost half a million Germans had been left homeless by the British raids. Another fourteen thousand had been killed or injured.

The Battle of Berlin profoundly affected the surviving Bomber Command aircrews. Morale plummeted, especially after it appeared all the sacrifices the men had made seemed all for nothing. Much of Berlin lay in ruins, but the German people seemed ever more resolved to fighting on. From the end of the Battle of Berlin to May 1945, the RAF crews tasked with carrying the offensive to the German people grew increasingly fatalistic. Having a 24 percent chance of surviving the campaign unscathed, safe at home in England were not odds anyone could endure with perpetual good cheer.

A formation of 44 Squadron Lancs high over England. The Germans learned to exploit the Lancaster’s lack of a belly turret by using their “Jazz Music”-equipped Bf-110s to creep under the Avros and fire up into them while safely inside the RAF aircraft’s blind spot.

Fires burn in the city streets below, silhouetting a Lancaster in its hellish glow. During some raids, the firestorms created turbulence and smoke clouds over ten thousand feet above the urban areas being consumed. RAF crews could navigate to the target by the flames, which could sometimes be seen from sixty miles away.

The Battle of Berlin and all its associated raids cost Bomber Command a thousand aircraft from November 1943 to March 1944. Here, a Halifax goes down after losing its right vertical stabilizer.

Bomber Command ground crews put the final touches on a Lancaster before the night’s mission. The dedication and work ethic the ground crews gave to their squadrons made the sustained air war against Germany possible. Without their devotion, the out-of-commission rates would have crippled the bombing effort. Yet, their thankless jobs received little recognition during the war or after.

The end of a very long day for an Eighth Air Force B-17 crew. The furious pace Spaatz and Anderson set for the crews in the spring of 1944 alarmed Doolittle, who fought whenever he could to give his men some time off.

Yet, German morale did not crumble. Instead the people Harris sought to kill or coerce into surrender only grew more resolute to continue the fight. Despite the damage to Berlin’s factories, war production quickly increased in 1944. Despite the hardships inflicted by the nocturnal bombers, the Germans would not quit. Four years after the London Blitz failed, the Battle of Berlin proved Douhet wrong again.

Bomber Command suffered a clear defeat over Berlin that winter. The crews started to wonder what the point of all this sacrifice was when nothing tangible ever seemed to be gained by it. Some historians have compared the crisis within Bomber Command in the spring of 1944 to the one the British Army experienced in France in 1917. Morale never collapsed, but it never fully recovered. A fatalistic resolve permeated Bomber Command until the end of the war.

Meanwhile, Doolittle’s Eighth Air Force crews finished out February with a 20 percent overall loss rate among the bombers. Five percent was considered sustainable in both the RAF and the USAAF. Doolittle continued to want to give his airmen time to recover, but his bosses, Fred Anderson and Spaatz, demanded that he maintain the pressure on the Luftwaffe.

To do so, the USAAF had to find another target that would force the Germans to come out and fight. Just as the British lost the Battle of Berlin, Spaatz stepped in and ordered the Mighty Eighth to hit the German capital in broad daylight. For the first time, the Americans would not target a specific factory complex. Instead, Berlin was to be carpet bombed under the winter sun. In retrospect, that shift away from precision targeting to area targeting marked a major step forward in the evolution of American aerial strategy, one that lead ultimately to the firebombing of Tokyo and the atomic attacks on Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

The RAF’s Mosquito ranked as the best all-purpose aircraft of World War II. It served as a night fighter, a strike aircraft, a fighter-bomber, as well as a pathfinder and reconnaissance platform. Here, a Mosquito lays waste to German ships caught at anchor in a Norwegian fjord in the summer of 1944.

Berlin lay 1,100 miles from the bomber bases in East Anglia. The distance involved had already cost the British dearly. During the night raids, the Luftwaffe took to intercepting the RAF over the North Sea, continuing the interceptions all the way to Berlin, then pursuing them almost to the British coast on their way out. With such a long exposure period, the RAF lost scores of bombers on these missions.

In the first week of March, the Eighth went to Berlin. Weather was an obstacle from the outset. The final days of winter left the Continent blanketed in thick cloud cover. It didn’t matter. Spaatz ordered the bombers into the air anyway.

For the survivors of the Big Week, the sight of red ribbon stretching all the way to Berlin on the briefing room’s wall map had a profound affect two weeks later. Groans, whistles, dead silence greeted the news of the target.

It didn’t help that the weather was awful. The first raid, set for March 3, misfired due to heavy clouds and storms the bombers encountered. Only the B-24s of the 3rd Bomb Division reached Berlin. The American campaign against the capital started more with a whimper than a bang.

The next day, snow fell in East Anglia. Doolittle wanted to scrub the mission. Anderson and Spaatz ordered him to get the bombers in the air. Five hundred Forts and Liberators headed for the target, only to run into even more appalling weather. Only sixty-nine tons of ordnance landed on Berlin.

Pilots of the Eighth Air Force’s legendary 4th Fighter Group pose for a snapshot prior to a mission in 1944.

In the furious air battles of Big Week and Berlin, the 4th Fighter Group’s tandem aces, Don Gentile and Johnny Godfrey, rose to fame as the Eighth Air Force’s most famous fighting pair. Gentile scored 19.83 aerial kills and 6 more on the ground during his combat career. Godfrey received credit for 28.99 air and ground kills before he himself was shot down and taken prisoner in the late summer of 1944.

A battle-damaged Fort burns on a farmer’s field back in East Anglia, having failed to reach its airfield after a mission over Germany.

That night, Doolittle wanted to give his airmen off-base passes. He saw their fatigue, saw their stress, and continued to worry that Spaatz and Anderson were pushing them beyond human endurance. They needed a break. Spaatz said no. The passes were cancelled.

The weather intervened and gave the crews the break they needed. Severe storms and fog grounded the Eighth Air Force on March 5. The next day, though, Spaatz wanted every bird in the air. Despite heavy cloud cover, Doolittle gave the “Go” order and 730 bombers found their way through the soup to wing their way east.

The Luftwaffe rose to challenge them with a vengeance. Vectored into elements of the 1st Bomb Division, an epic air battle erupted over the German frontier as waves of interceptors waded into the 91st, 92nd, and 381st Bomb Groups. Frantic gunners laid on their triggers as the 109s and 190s flashed past through their formations. The 91st took a beating, losing six Forts and sixty men. The other two groups in the wing lost seven more.

Moments later, a squadron of Messerschmitt Bf-109s slipped through the escort screen to make a head-on attack on the 457th Bomb Group. One German pilot misjudged his run and collided into 2nd Lt. Roy Graves’ B-17. Locked together, the wreckage from both planes spun into Graves’ wingman, 2nd Lt. Eugene Whalen’s Fort.

The formations soldiered forward. Fresh interceptors struck the unluckiest group in the Eighth Air Force. This was the Bloody Hundredth, and again they earned their reputation. Caught unprotected by Mustangs or Thunderbolts, the Hundredth encountered upwards of a hundred German fighters or more. In seconds, they dove down into the American combat box in another furious head on pass. The entire 350th Bomb Squadron—the high element in the box that day—went down in flames. Ten bombers in a blink of an eye. Still the buzz saw continued. Before their return to England, the 100th Bomb Group lost fifteen of its twenty planes.

The Eighth made no effort to hide their destination. The Luftwaffe controllers scrambled everything that could fly and fight. Even units that were serving on the Eastern Front received orders taking them over Berlin. The fighting raged across the length of the Reich until late afternoon when the final battle-damaged burning bombers crash-landed back in East Anglia.

Spaatz was right: The Germans would fight for Berlin. Sixty-nine bombers had gone down during the day. The Germans lost sixty-six fighters.

56th Fighter Group ace Francis Gabreski received national press for his exploits over Germany while scoring twenty-eight air and ground kills. But even as the veteran pilots of VIII Fighter Command took a heavy toll of the Luftwaffe’s aces defending the Third Reich, the merciless war of attrition claimed plenty of American ones as well. Gabreski crash-landed during a strafing run against a German airfield in July 1944 and was taken prisoner. By the end of the summer, the Luftstalags held many of the VIII’s top aces, including fellow Wolfpack ace and former commanding officer Hubert “Hub” Zemke.

Francis Gabreski and members of the 56th Fighter Group stage a celebratory shot in the group’s officer’s club at Halesworth.

Forts of the 384th Bomb Group over Berlin during the March 6, 1944, raid. The lead bomber, Shack Rabbit, survived the air war only another month. During an April 24, 1944, raid to Oberpfaffenhofen, Shack Rabbit was shot down over France. The Fort’s pilot, Lt. Walter L. Harvey, and four other members of the crew were able to escape back to England, thanks to the French underground. The 384th Bomb Group lost eight bombers that day, over a quarter of its strength.

The next day the weather closed in, but on March 8, Spaatz ordered the Eighth to hit Berlin again. Thirty-seven bombers went down. The Luftwaffe lost fifty-five interceptors.

Worn out, pushed to the edge of human endurance, the German pilots had reached a breaking point. Since the Americans commenced attacks on Berlin, some of the Luftwaffe’s best fighter leaders had been killed in the Reich’s cloud-strewn skies. Egon Mayer, Anton Hackl, Hugo Frey, Gerhard Loos, and Rudolf Ehrenberger—all bomber-killing experts and aces with a combined 471 aerial victories—had died in battle between March 2–8.

The Luftwaffe simply couldn’t sustain the loss of such veteran pilots. By this point in the war, their experience and leadership were the only things holding together the fighter geschwaders.

On the other side of the fence, the American crews had been pushed to the ragged edge of exhaustion as well. Doolittle fretted and worried about them, but Spaatz and Anderson were unrelenting. They laid on another strike against Berlin for March 9. There would be no respite for the crews, many of whom had already flown on every other mission to the capital.

As an engine mechanic goes about his business, an armorer pauses as a local farmer’s wife feeds her ducks right there in the parking area of the Eighth Air Force station. Civilians lived clustered around the edges of the American bases and frequently came and went as they saw fit.

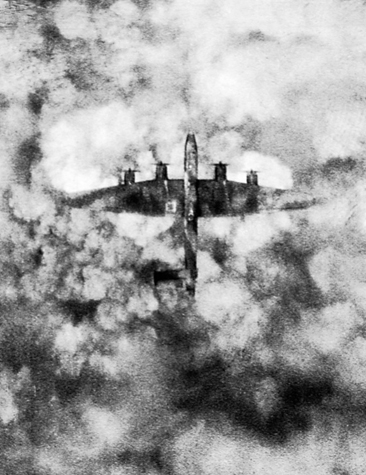

One of the 2nd Bomb Division’s B-24 groups makes its way toward Berlin during the March 6, 1944, raid.

The 306th Bomb Group, 1st Division, closing in on Berlin during the Mighty Eighth’s epic campaign against the German capital. The Americans succeeded in delivering a body blow to the Luftwaffe by making its fighter force come out and fight to defend Berlin.

A 56th Fighter Group Wolfpack P-47D Razorback Thunderbolt escorting a B-17 formation during one of the March Berlin raids. This particular P-47 survived the brutal attrition over Europe until August 3, 1944, when it was shot down over Europe.

That morning, the crews gathered in the briefing room and learned they would bomb Berlin again. Given the desperate battles and loss of so many friends over the past week, it would be difficult to underestimate the fear and despair that the news of the day’s target evoked in these young Americans. Some of those men were short-timers; this would be their twenty-fifth mission. Instead of an easy milk run and a flight back home, they faced another grueling ordeal over the heart of the Reich. One such veteran described how he became a “nervous wreck” as he and his comrades struggled to finish their last four missions in the midst of this blitz on Berlin.

The 94th Bomb Group over Berlin in early March. The pace of combat operations and the level of attrition during the spring of 1944 made chances of survival quite dicey for the crews of these B-17s. The Fort in the picture’s foreground was severely damaged a few weeks later during a raid on Brunswick on March 23, 1944. The crew managed to coax the crippled bird to the English Channel, but they finally had to set it down in the water. All aboard were killed.

Throughout the Berlin campaign, the weather played havoc with the Eighth’s operations. Several days’ raids had to be canceled, especially after an unseasonal snowstorm dusted the East Anglia bomber stations.

Chow Hound, a 91st Bomb Group B-17 over Berlin during the March 8, 1944, mission. Thirty-seven bombers went down during this raid on the Reich’s capital, but the previous week’s fighting had hammered the Luftwaffe’s interceptor force. The next day, the Germans could not defend Berlin against one more attack, and the Eighth suffered only light losses. Chow Hound and her crew survived the offensive against Berlin, only to be lost over France in August. Nine men went down with their B-17 and died.

A 93rd Bomb Group B-24 en route to Friedrichshafen. After the Berlin campaign, the Eighth Air Force did not relent. Near daily deep penetration raids sustained the pressure through March and April, forcing the Luftwaffe’s exhausted interceptor pilots to rise and do battle against ever-longer odds. This particular B-24 endured the spring offensive before D-Day, only to go down over Belgium on September 21, 1944.

A 34th Bomb Group B-24 on its bomb run. The Eighth Air Force expanded to include by the Berlin raids two bomb divisions of B-17s and one of B-24s.

Heavy cloud cover obscured most of Germany that day. The bombers hit Berlin and other cities using radar to guide them into the target areas. But instead of swarms of German fighters to greet them, the grey winter skies were devoid of interceptors. Weather, catastrophic losses, and fatigue conspired to keep the Luftwaffe on the ground. Flak shot down nine bombers. Berlin had been raided, and the Germans could no longer defend it. A turning point had been reached. By the end of the month, the Luftwaffe lost 56 percent of its available fighters and 22 percent of its interceptor pilots. Twenty-five more veteran aces would die attacking the bomber streams between March and May.

The commander of the fighter defenses in the north (Jagdgruppe I), later remarked, “The American forces captured air supremacy over almost the entire Reich . . . and this meant the complete collapse of Germay’s position as an air power.”

Major Jim Howard, a former Flying Tiger ace with six kills, joined the 354th Fighter Group as a squadron commander in time to reach England with the unit in December 1943. On January 11, 1944, he encountered about thirty Luftwaffe fighters attacking the B-17s of the 401st Bomb Group. Alone, Howard waded into the German interceptors and shot down six of them. He saved the 401st from suffering the fate of so many other bomber groups that had been singled out by the Luftwaffe’s fighters. For his actions that day, Howard received the Medal of Honor, the only fighter pilot in the Eighth Air Force to be so decorated.

Jim Howard, George Bickell, and Owen Seaman, the 354th Fighter Group’s squadron commanders in early 1944, pose on the flight line before a mission. Bickell and Seaman had both been at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and had endured the Japanese surprise attack. Without the 354th and the arrival of more P-51 Mustangs in theater, the Berlin strikes in March would never have been possible.

It would not be easy. Plenty of fight remained in the jagdgeschwaders, and at times they could inflict serious damage. On March 18, they punished the 2nd Bomb Division’s B-24s for a terrible mistake made over Friedrichshafen when the 44th Group executed a 360-degree circle over the target area. The trailing groups, confused by the unscheduled move, abandoned their bomb runs and switched to a secondary target. In the process, the Liberators became strung out. At that moment, the Luftwaffe hit them with seventy-five fighters. Attacking in waves of six, they sent fifteen 392nd Group B-24s down in flames.

Old Glory was one of them. Damaged by flak that had already wounded or killed two members of the crew, the Liberator struggled to maintain formation with one engine feathered and two fires raging. As the pilots fought to save the aircraft, German fighters pounced. Bullets flayed the fuselage. The nose gunner cried out for help. The next attack knocked out the oxygen system; the Lib started to buck and heave, growing increasingly out of control. The tail gunner had moved forward and was in the waist when an oxygen bottle overhead took a direct hit and exploded. The blast threw the tail gunner, Chester Strickler, straight through the waist window. As he parachuted to the ground, the Liberator was reduced to falling debris. He was its lone survivor.

Though the tipping point had been reached, plenty of desperate, hard fighting remained.

Starting a 381st Bomb Group B-17’s engines required coordination between pilots and ground crews. Here, a ground crewman checks out the right inboard engine as it sputters to life, keeping a fire extinguisher handy in case something went wrong.

The 452nd Bomb Group over Berlin during the March 9, 1944, raid. The surprised Americans, jaded and cautious from the bloodbaths over Berlin since March 2, expected heavy losses. Instead, they found the cloudy skies virtually free of Luftwaffe interceptors.

Hub Zemke ranks as one of the greatest fighter leaders of World War II. He shaped the 56th Fighter Group into one of the most effective in the history of the USAAF. He scored 17.75 confirmed kills during his tenure in the VIII Fighter Command before being lost over Germany in October 1944. He spent the rest of the war in a POW camp.

During the spring and summer of 1944, the skies over Germany filled with contrails almost every day.

Little Miss Mischief after a mission over Nazi-held Europe. Thanks to the tireless efforts of the ground crews, such crash-landings rarely kept a B-17 out of action long. They performed miracles with mechanical ingenuity.

A crippled Fort from the 381st Bomb Group belly-lands back in England. The weight of the aircraft usually crushed the ball turret during such desperate landings. If the turret had jammed or had been put out of action by battle damage, the gunner inside faced a grim reality: his life for the rest of the crew’s.

A German-eye view of a 452nd Bomb Group B-17G about to drop its bombs on Berlin during a raid in the spring of 1944.

The gut-check moment: on the bomb run, straight and level, sitting targets . . . the crews could only pray they would come through unscathed. It all came down to chance—and perhaps faith.

Hauptmann Anton Hackl, one of the Luftwaffe’s leading bomber-killers, was among the twenty-eight German aces to be killed during the furious fighting in the spring of 1944. The attrition rate on German pilots grew so severe that their life expectancy in combat averaged eight to thirty days.

Another Luftwaffe casualty during the spring was 275-kill ace Gunther Rall. He was wounded in action flying against the Americans and was knocked out of action for several weeks.

Another shot of the 452nd Bomb Group at its release point over Berlin, March 6, 1944.

The remains of a battle-damaged B-24 after crashing back in England. Six wounded, four miraculously escaped harm.