MUSIC FOR ORCHESTRA AND THE FIRST QUARTETS

![]()

The First Symphony and the Prometheus Ballet

In 1795 Beethoven sketched some ideas for the first movement of a C-major symphony, then let the project lie fallow. He picked it up again in 1799, revised and completed it, and had it performed as his First Symphony at a concert in April 1800, along with a Mozart symphony, an aria from Haydn’s Creation, and other new compositions of his own, including his Septet. The 1795 torso is of interest only as it foreshadows some material in the finished First Symphony. Realizing that the main C-major theme in the sketched first movement would not work in his more developed conception, Beethoven transferred it to the symphony’s finale, where in altered form it became the sprightly first theme. By presenting the initial tonic C major chord as a dominant seventh, Beethoven maintains and dramatizes the idea of opening with a short slow introduction, clearly in the manner of Haydn’s London symphonies. This way of beginning was celebrated as a coup, although it is in fact a harmonic condensation of a familiar opening gambit inherited from Mozart and Haydn.1

In all, the First Symphony contains attractive features within an essentially simple larger design. Its first movement displays some progressive touches, such as the elegant use of antiphonal solo wind instruments in the second thematic group of the exposition and the darkly colored pianissimo modulatory episode that follows. And the climax of the first movement is built on the same harmonic sequence we heard at the opening of the slow introduction, which returns to form the culmination of the coda.2 The slow movement is perfunctory when compared with those of the piano sonatas and piano trios of these years, let alone those of the Opus 18 quartets.

But the third movement stands out. This “Menuetto” is really the first Beethoven symphonic scherzo. Marked Allegro molto e vivace, it is a long, brilliant, ambitious movement with a far-reaching modulatory scheme in its second section and a fullness of realization that eludes the other movements. No other composer of the time could have written even a phrase of the Menuetto, which leaps out of the symphony as its most memorable movement. The finale, all lightness and wit, is a clever 2/4 sonata-rondo that pairs well with the finale of the First Piano Concerto even if it lacks the sharp contrasts by which the concerto’s solo and tutti exchanges enliven the action.

Alongside the more adventurous works of these years, the First Symphony fails to impress. As he prepared to give the public a first taste of his prowess as a symphonic composer, Beethoven played it safe rather than provoke his audience. He avoids the quirks and eccentricities (such as the abrupt contrasts of dynamics, accents, tempos, and musical ideas) that had come to be the order of the day in his sonatas and chamber music but that annoyed his critics. So the First remains a trial run, not a work that comes up to the standard of the “sublime” that Johann Georg Sulzer and other aestheticians had set for the symphony nor, in practical terms, the artistic standard set by Haydn and Mozart in their later symphonies. The same ambition to please is written all over his Septet, Opus 20, a divertimento companion to the First Symphony intended for salon performance. In his later symphonies Beethoven took the entire genre into his hands, remolded it, and flung it beyond all earlier boundaries, putting unheard-of demands on performers and listeners and transforming the parameters of the symphony. In later years the First remained a distant memory of an earlier, attractive and domesticated Beethoven that survived only in his lighter compositions intended for amateurs. As late as 1821 a critic could refer to the First with unwitting irony as “one of his earlier, more comprehensible instrumental works.” If the critic had sympathetically followed Beethoven through the immense development of the later years, he would have had to agree that, except for the third movement, it lacked anything truly new. Berlioz minced no words in a review included in his A Travers Chants:

[I]n this symphony the poetic idea is completely absent, even though it is so grand and rich in the greater part of the works that followed. Certainly it is music admirably framed: clear, vivacious, although only slightly accentuated; cold, and sometimes even mean, as in the final rondo, a true example of musical childishness. In a word, Beethoven is not here.3

The path from the First to the Second Symphony is not direct but runs through Prometheus, the ballet that Beethoven wrote in the winter of 1800–1801 for the Italian ballet master Salvatore Viganò, who premiered it on March 21, 1801, in the Hofburgtheater. Though the music is attractive enough, the work is more important for its dramatic qualities. It shows Beethoven’s acquiescence in the current view that ballet music was primarily intended for entertainment and must be easier and lighter than music for the concert hall. Only later, in writing incidental music for Coriolanus and Egmont, would he turn to the more serious modes of expression demanded by music for spoken drama, which meant vastly more to him than ballet. Still, Prometheus is of interest precisely for its special effects and limitations: it shows Beethoven exploiting instruments and coloristic orchestral effects that would never appear in his symphonies or serious dramatic overtures. Among them are No. 5 (from Act II), in which the muse Euterpe plays the flute, presumably with a simulated musical performance by the demigods Arion and Orpheus, famous musicians of antiquity. Here Beethoven opens with an Adagio introduction for solo harp with rolled chords, probably strummed by Orpheus; then strings provide a pizzicato accompaniment to concertante wind passages (Euterpe’s solo). At last the whole gathers to a climax. Here a solo cello cadenza takes over the ensemble and leads the orchestra through a handsomely melodic Andante quasi Allegretto that in another context could have been the slow movement of a popular and beautiful cello concerto in Beethoven’s most ingratiating first-period style.

Elsewhere the score abounds with scenic effects, from the opening storm (“La Tempesta”), in which Prometheus runs through the forest, to an Allegretto “Pastorale” (No. 10) that dimly foreshadows the finale of the Sixth Symphony. But the pièce de résistance is the Finale, in which the E-flat ballroom contredanse in 2/4 receives extended orchestral treatment; it even uses another of his contredanses, in G major, as its middle section. But the dance sticks tight to its simple binary form, receiving no development—for in ballet there could be none.

What Viganò’s Prometheus meant to contemporaries is worth considering, so far as we can piece it together from scant evidence. The full title is The Creatures of Prometheus, and it is labeled “a mythological allegorical ballet.” The protagonist is the Titan Prometheus, portrayed here not as suffering victim but in his benign role as the molder of human civilization. Prometheus literally shapes humankind by bringing to life two clay statues, a man and a woman. From an 1838 synopsis of Viganò’s plot we learn that “the two statues come to life . . . [then] Prometheus beholds them with joy . . . but cannot awaken any feeling in them that shows the use of reason.”4 Prometheus despairs of his mute creatures and plans to enlighten them by exposing them to the “higher arts and sciences.” In the second act, set on Parnassus, the stage is filled with a parade of mythological figures: Apollo, the nine Muses, the Graces, Bacchus, Pan, then Orpheus, Amphion, and Arion. At the end, Melpomene, the muse of tragedy, appears and abruptly shows the inevitability of death by killing Prometheus before their eyes. But the necessary happy ending of neoclassical drama occurs just as suddenly, if hardly more credibly, when Thalia, the muse of comedy, “holds her mask over the faces of the two mourning creatures . . . while Pan, leading his fauns, calls the dead Prometheus back to life, and so the tale ends with festive dancing.”5

Prometheus was called in the original playbill a “heroic, allegorical ballet.” The term “heroic,” as applied here, has been associated with Beethoven’s use of the ballet finale material in the Eroica finale, and thus the identity of the ballet’s theme with the symphony’s finale might seem to extend the allegory to both. But the Prometheus of the ballet is not the rebellious Titan who brought fire to humanity and then suffered Zeus’s punishment by being bound to a rock while his liver was gnawed by a vulture. He is not the monumental Prometheus of Aeschylus, nor that of Goethe or Shelley, who stands up to the gods. This Prometheus is presented rather as an Enlightenment philosopher and teacher who brings reason and knowledge to the unlettered and ignorant “creatures”—Rousseau’s noble savages on the ballet stage—men and women in a pre-civilized, preliterate state.

Behind Viganò’s work lay a more current subtext. By 1800 Napoleon Bonaparte was the talk of Europe. As a military hero he had risen to fame with his lightning victories at Toulon and in Italy, where, at twenty-five, he had become commander of the French armies. Italian patriots glorified Bonaparte as the champion of their long struggle against Austrian despotism, and in 1797 the poet Vincenzo Monti hailed him as the liberator of Italy in an epic poem called, significantly, Prometeo. It is possible that Beethoven’s decision to use the Prometheus finale in the fourth movement of his Third Symphony, which was not only dedicated originally to Bonaparte but was even intended to carry his name, reflected his awareness of a connection between Prometheus as mankind’s mythic liberator and Napoleon as a modern hero.6 This possibility is not undermined by the indirect path from Prometheus to the Eroica through the Opus 35 Piano Variations, which in turn laid the basis for his first concrete ideas for the symphony.

The French Dimension and Military Music

Stirred like all his contemporaries by the upheavals in France, Beethoven was receptive to the vigor and power of French Revolutionary and post-Revolutionary music, above all in two domains. One was French opera. He admired the operas of Cherubini, which with others from France were becoming increasingly popular in Vienna between 1802 and ’04, so much so that Beethoven could tell Rochlitz in January 1804 that “Schikaneder’s empire has really been eclipsed by the light of the brilliant and attractive French operas.”7 He knew Cherubini’s Médée (1797) and Les deux journèes (1800), serious and effective works that brought a new and powerful voice to French opera.

The other domain was the new school of virtuoso French string playing. Beethoven’s acquaintance with the new generation of violinists had begun in Bonn but continued in Vienna, where he met Franz Clement and even studied violin with Schuppanzigh. But he soon became fully aware of the new traditions that had been established in France by Viotti and his followers, especially Pierre Baillot, Pierre Rode, and Rodolphe Kreutzer, with whom he played a violin sonata at a private concert at Lobkowitz’s in April 1798.8 When Baillot came to Vienna in 1805 he met Beethoven at a tavern and later expressed surprise when he found the celebrated composer to be quite friendly, “although his portraits always show him to be so unattractive and almost fierce.”9 Similarly, Beethoven’s exposure to Jean Louis Duport in Berlin in 1796 had stimulated his awareness that the new French virtuosity now extended to the cello.

The music of postrevolutionary France aroused and inspired the whole European world. Traditional French music, certainly French opera, had been available in Bonn in the 1780s, and continued to be heard in Vienna in the 1790s as musicians rapidly adjusted to the cultural and political currents of these years. Responding to the new national fervor and mindful of the volatile swings of domestic politics, French composers quickly developed popular idioms that caught the spirit of the times—whether in works that directly reflected the new ideology of political liberation plus French military exuberance, or in grandiose works designed to symbolize the national pride and mass solidarity on which the leaders of the new regime depended for support. Thus propaganda songs, choral hymns dedicated to liberty, equality, and fraternity, and, most important, stirring military marches and marching songs were the order of the day. A government decree directed that La Marseillaise and other songs were to be sung before every performance in theaters all over France, thereby sparking the singing of a popular song or anthem before sports events and, in some countries, theatrical performances, that has lasted down to our time. Stage works and festivals commemorating Revolutionary milestones, such as the taking of the Bastille on July 14 or the founding of the Republic on September 22, served as pretexts for large-scale public assemblies marked by patriotic pageants, of which there were seven or eight every year in France between 1790 and 1800.10

By far the most famous single piece, the one that the world could never forget, was La Marseillaise, written on the night of April 25, 1792, by the soldier, poet, and composer Claude-Joseph Rouget de Lisle, and first called Chant de guerre pour l’armée du Rhin. Rouget de Lisle was a young lieutenant in the French army and also a violinist and singer, assigned to duty at Strasbourg, when he wrote both the words and music of this amazing piece. When it was immediately adopted by a battalion from Marseilles, it became wildly popular under the name The Marseillaise’s Hymn. It swept the field in all of France just five months later, when François-Joseph Gossec orchestrated it and inserted it into a lyric scene called Offrande a la Liberté that was put on at the Paris Opéra. No music or text more completely captures the military spirit of its time, or any time; it is a “tune to set the pulse racing and the blood coursing.”11 Embodying in one stroke the surge of national and military pride then felt across France, and sung by French soldiers marching to battle in their first major campaigns against the enemy states of Europe, La Marseillaise remained a perfect symbol. It has stood ever since as the epitome of a militaristic national anthem, as we see from countless arrangements; quotations of the melody in songs or concert works by Schumann, Wagner, Liszt, Tchaikovsky, and others; and its emotional pull when sung by French citizens in film scenes reflecting French national pride, as in Grand Illusion and Casablanca.

In Beethoven’s time everyone knew it and writers as far removed from France as were Klopstock and Goethe admired it. After a battle in which it was sung, August von Kotzebue, a German dramatist, praised Rouget de Lisle by asking, “Brute, barbarian, how many of my brothers have you not killed?”12 Although the Marseillaise faded in France during the Napoleonic and Restoration eras, it came back in the 1830s, by which time it had been translated and taken up abroad, had even been given German words, and had become a German popular favorite.

Beethoven knew a great deal about popular songs, especially national ones, and wrote variations sets on several, including “Rule Britannia” and “God Save the King.” He also composed military marches throughout these years. When it came to the battle scene in his Wellingtons Sieg (“Wellington’s Victory”) of 1813, he had the British march to “Rule Britannia” and celebrate at the end with, appropriately, “God Save the King.” The French army in this work marched not to the strains of La Marseillaise but to the old-fashioned though equally durable “Malbrouck s’en va-t’-en guerre” (“Marlborough Goes Off to War”).13 In the heady atmosphere of the Austrian victory celebrations of 1813 La Marseillaise would have been subversive and probably illegal, and the older tune fitted the losing side.

Composing marches for military band, or with words as marching songs, or for civilian bands to play in order to arouse patriotic fervor, was then a widespread popular pastime. As armies all over Western Europe marched into battle year after year, French soldiers sang the Marseillaise and other tunes by François-Joseph Gossec, André Gretry, Jean-François Le Sueur, Etienne Méhul, and Luigi Cherubini. British battalions marched to music by Thomas Busby, John Callcott, William Crotch, James Hook, at times even Handel and Haydn. Both Handel and Haydn, if anyone asked, could be considered adopted Britons in the wake of their personal successes in England, but it was ironic that the Britons could sing Haydn, considering that he had composed the great “Kaiser-Hymne” (“Emperor Hymn”) in 1797 at the request of Austrian ministers who were anxious to revive the flagging national will to continue the country’s war against France. Austrian infantrymen in the Napoleonic years could counter with marches by Süssmayr, Paer, Hummel, and Beethoven.14

Included in Beethoven’s large catalogue of minor works are four quick-step marches for military band, plus a polonaise and two ecossaises, all written between 1809 and 1816. As a genre, the rapid march plays a telling role in some of the works on a higher level: witness the pithy, brilliant military march for Pizarro’s soldiers in Fidelio; the march in the wonderful cadenza for the piano version of the Violin Concerto; and the up-tempo, stylized marches sprinkled among his instrumental works, even late works such as the Piano Sonata Opus 101, the Ninth Symphony finale, and the A minor Quartet, Opus 132. Military elements, especially marchlike rhythms, found their way into concertos of the period, to some extent in Mozart and certainly in Beethoven, right down to the “Emperor” Concerto.15 It almost seems as if the dramatic confrontation of solo instrument with orchestra in the classical concerto may have spurred a sense of contentious striving and of force of oppositions that suggested an affinity with the rhythms of military music.

In this bloody era cursed with incessant war and with chauvinism rampant on all sides, national anthems sprang into being, literally for the first time in history. The earliest anywhere had been “God Save the King,” first heard in 1745 after a British military defeat. For a long time this sturdy English melody grew so popular that other countries, faute de mieux, made use of it with appropriate words as their own version of a national anthem—the list included Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland, Russia, and even the United States. In Germany it was sung as a patriotic anthem in various German states from the 1790s through 1871, the year of German unification, and it was still being used as late as the First World War with the words “Heil Dir im Siegenkranz” (“Hail to Thee in the Wreath of Victory”).16 Only in 1922 was it superseded in Weimar Germany by the proleptic adaptation of Haydn’s hymn for the kaiser as “Deutschland, Deutschland, über alles,” which, with words purged of seeming German claims to international domination, is still in use today. But “God Save the King” was still preeminently British in Beethoven’s time, as he knew when he used it to celebrate Wellington’s victory over the French at Vittoria. Precisely at this time musicians were creating new anthems for their own countries, and all through the nationalistic nineteenth century new European anthems sprang up on demand; in some cases—“The Star-Spangled Banner,” for example—these anthems were not formally and officially adopted until the twentieth.17

The spirit of national urgency in the Marseillaise colored much French music of the time, and the widespread adoption of march rhythms, overtly in some “heroic” works and more subtly in others, arose from the growing awareness of music as a public art that could powerfully express contemporary political and spiritual energies. This feeling was sparked by French revolutionary fervor in 1789 and continued to blaze as France embarked on its European campaigns that seemed never to end. Even during peacetime the new France, first under the Directories and then under Napoleon, continued to spawn new modes of musical expression, most grandly in choral compositions designed for public performance but also in opera, orchestral works, and piano music. During Beethoven’s most impressionable years, from the late 1780s to about 1800, French works for public political celebrations were often performed outdoors with extravagant numbers of performers that could rise into the hundreds, sometimes the thousands. Such music had to be “simple, direct, striking, memorable, and—most of all—flexible. . . . [I]t breathes the spirit of a new age . . . frankly directed to large audiences, to simple, communal sentiments.”18

Whatever the absolute musical quality of the works stemming from France, they showed composers seeking higher and more arcane forms of expression in the hope that they too could address audiences beyond the chamber music rooms of patrons, and even beyond the theaters and concert halls in which crowds of several hundred could hear symphonies. It became clear that a composer seeking to represent the spirit of this new age and be a major voice in that representation had to produce music that reached large audiences, and do so in bold strokes that would ring out far beyond the immediate confines of music-making spaces. The music, of course, would need to have enough force and cogency to address not just immediate listeners but the world beyond. And of all composers active around 1800, Beethoven was the one most capable of expressing this élan, with its new aesthetic of power and complexity. The latent connection to French music and to national and military music in his style—later called the “heroic” style—was subtly apparent to knowledgeable musicians and commentators of the time. At the same time, works such as the Eroica and Fifth Symphony, which manifest this style in its strongest form, carried the heroic aesthetic to heights of which no French or other contemporary could dream.

Beethoven began work on the Second Symphony as early as 1800 and continued sketching it through 1801 and into 1802, although it was probably not ready when his brother Carl offered it to Breitkopf & Härtel at the end of March. Beethoven came back to it later that year in time to get it ready for its premiere in April 1803. Then it took another year for its publication, in March 1804. These dates are important because it appears that Beethoven often took the publication of his previous symphony as a springboard for intensive work on the next one. Thus he was certainly working on the Second when the First Symphony was published in December 1801, that is, published in parts, not score, following the custom of this time. Similarly, when the Second appeared, he was deep in the toils of composing the Third. The publication dates also carry weight because Beethoven often revised his works after their first performances, especially orchestral works, which took time to publish, and he often kept on revising as long as he possibly could, that is, until the work was actually in print. Thus the final touching-up of the Second Symphony, which was extensive, must have taken place while he was in the midst of working on the Third.

From the sketches we can see that the idea of a slow introduction was integral from the start, though originally in duple not triple meter. The early ideas for the introduction include a slow-tempo version of the march theme that he later transferred to the Allegro exposition as the main second-group theme. Accordingly, the spirit of the military march was firmly established from very early on, and however expanded the first movement became, it never lost this spirit. The first Allegro theme was originally a simple triadic figure (1–3–1–5–1–3–1) but there is more to it than first appears: its interval sequence is nearly identical to the one that Beethoven later used for the opening of the first theme of the Eroica. In the sketches for the Second this theme is rhythmically too static to serve his purposes. In these sketches it evolves into what became the final version, which maintains the linearized tonic triad as its basic frame but cuts the material neatly into well-defined segments that can function both together and apart. The final version has a rhythmic form typical of the early middle period, with a long-held first note and four brisk sixteenths at the end of the measure.

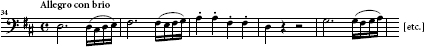

(a) Sketch for Symphony No. 2, first movement, main theme, from sketchbook Landsberg 7, p. 38 (Source: Ein Notierungsbuch von Beethoven, ed. Karl Lothar Mikulicz [Leipzig, 1927]):

(b) Symphony No. 2, first movement, main theme:

The first movement leaps far beyond anything in the First Symphony, even the earlier work’s excellent Menuetto, in dynamic action and dramatization of ideas. The slow introduction is the widest ranging in harmonic span that Beethoven had written up to this time, and it glows with touches of orchestral color he had never tried before. By marking it Adagio molto (the same as for the short introduction to the First Symphony) he brings a strong tempo contrast between introduction and the main section, marked Allegro con brio.19 The main Allegro exposition then surprises us by presenting the first theme not as a complete melody in an upper register but as a partial theme in the lower strings, a theme that then invites development of its strongly profiled motivic units and energetically pursues a wealth of contrasts.

The slow movement, one of the most sensuous of all Beethoven’s Larghettos (a tempo that Mozart had reserved for his most beautiful slow movements), sank deeply into the musical consciousness of contemporaries and subsequent generations, becoming, as Tovey said, the touchstone of what is beautiful and childlike in music. For Beethoven the tempo Larghetto is new in his instrumental music (if we exclude the little “Electoral” Sonatas of 1783), and he used it elsewhere for delicate works and movements such as the song “Adelaide,” the slow movement of the Violin Concerto, and the introduction to the finale of the Quartet Opus 95. The opening theme, in its pure sonorities of strings all in middle and high register, and its repetition with clarinets, bassoons, and horns, all piano, anticipates the Romantic orchestral effects of Schubert and Mendelssohn. For Berlioz this movement was “a delineation of innocent happiness hardly clouded by a few melancholy accents.”20 A vast step beyond its counterpart in the First, this slow movement is a large-scale sonata form that finds room within its lyrical expansions and contrasting thematic elements for a full development section, plus a retransition to the home tonic and the main theme that is as beautiful and nostalgic as anything Beethoven ever wrote.

That Beethoven labored to achieve this quality we could easily infer, but Ries tells us so explicitly. He says that this slow movement was “so beautiful, so purely and happily conceived, and the voice-leading so natural, that one can hardly imagine anything in it was ever changed”—but Ries also says that in the autograph score the second violin and viola parts at the beginning were so heavily covered with corrections that he could hardly make out the original notes.21 To which Beethoven replied, when Ries queried him, “it’s better that way.”

The manic finale of the Second outdoes the first movement in energy and originality. It opens with a wild and powerful figure on the dominant that stops with an abrupt accented two-note motif on the downbeat, then touches off a rapid continuation that ends again with the same two-note whiplash figure (*W 14). Essential to the conception is that the finale should open in high tension and then extend and hold the hot current in motion right to the end, culminating in a final peroration that amazed contemporaries and evoked such criticisms as “colossal” (in a negative sense), “tumultuous,” and “untamed.”22 The symphony crosses new boundaries, moving into a range of dramatic expression in which the strongest possible contrasts occur in unexpected immediacy—movement to movement, section to section, idea to idea. Breaks in texture, breaks in continuity, powerful motoric rhythms that suddenly stop—these erupt before the listener’s ear with a violence that had never been heard in symphonic writing up to this time. No wonder the critics found it bizarre—it was too much for traditional ears accustomed to gentler, more gradual contrasts. This symphony signaled that from now on in Beethoven’s orchestral works power and lyricism in extreme forms were to be unleashed as never before, that the stark dramatization of musical ideas was to be fundamental to the discourse, and that contemporaries, ready or not, would have to reshape their expectations to keep up with him.

Opus 18: “I have now learned how to write string quartets”

Since its emergence as a genre, essentially created singlehandedly by Haydn in the 1760s and later brought to its first maturity by him and by Mozart, the string quartet had grown in stature to be the highest and most demanding of musical categories, a “noble genre,” as Seyfried called it.23 That it stood apart was not just a matter of idle preference or snobbish taste. The new schools of violin playing that had risen to virtuoso heights in the last forty years of the century, led by Leclair and Viotti, were followed ambitiously by cellists and even a few violists. All of this was reflected in expanded writing for strings in all genres but nowhere more strikingly than in the string quartet. This new type of ensemble, divorced from the vestigial Baroque keyboard continuo, made up exclusively of homogeneously blended string instruments that had the widest range and quality of tone, warmth, expressivity, and flexibility, aroused a strong response from performers and patrons that composers soon rushed to fulfill. The quartet became a test of compositional ability for young composers, a way of showing their skill in writing idiomatically for four equally important parts with no fillers or patchwork to hide deficiencies in imagination or dull material. And by the time Beethoven came around to quartet writing in the later 1790s, Mozart’s mature quartets were all very recent classics, prominent on the horizon. Haydn, the law-giving master of the genre from its inception, was still turning out new quartets on the same high level to which he had accustomed the musical world since the early 1770s, when his Opus 20 had set a very difficult standard for all his contemporaries and successors to meet.24

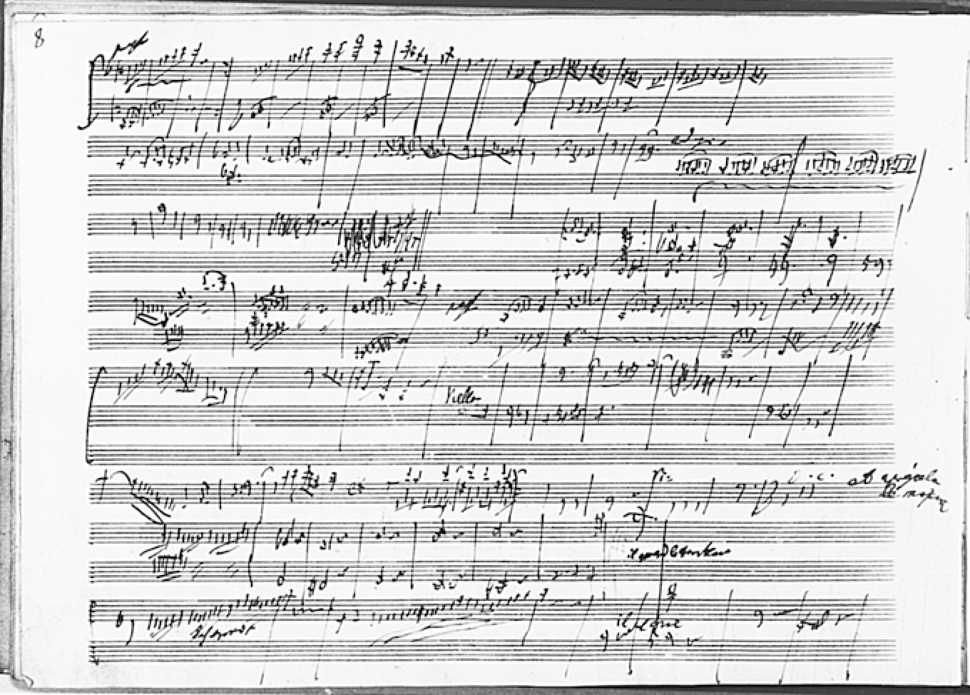

Sketches for the slow movement of the String Quartet Opus 18 No. 1, containing references in French to scenes from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. (Staatsbibliothek, Berlin)

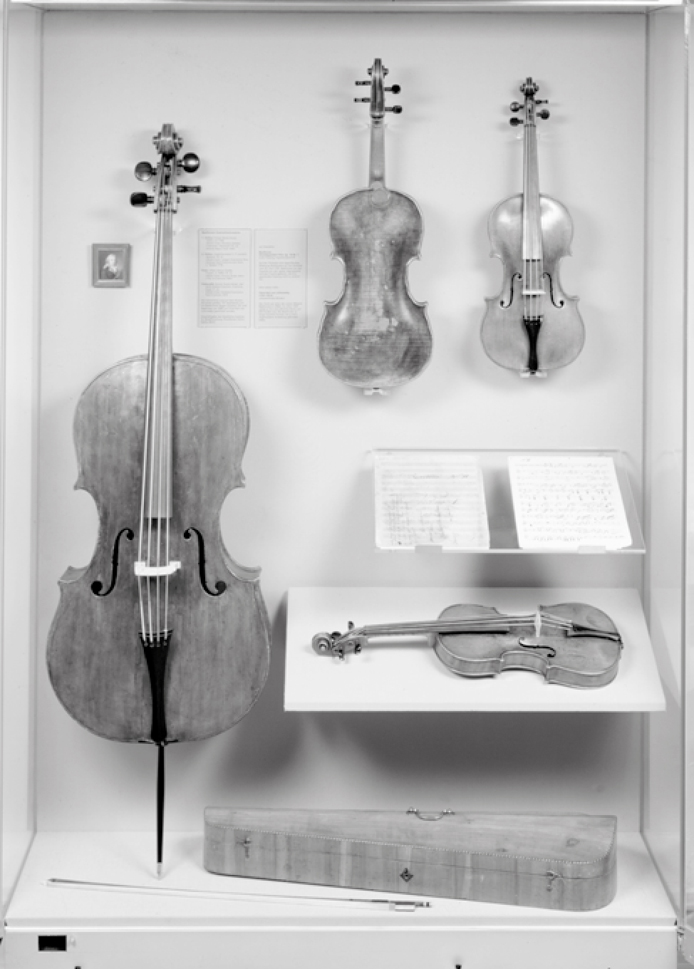

A set of Italian stringed instruments given to Beethoven by Prince Karl Lichnowsky around 1800. (Beethoven-Haus, Bonn, on permanent loan from the State Institute of Musical Research, Preussischer Kulturbesitz)

Beethoven was probably wary of the high expectations that musicians held for him in this genre above all, and no doubt also saw Haydn’s masterly Opp. 71 and 74 Quartets directly before him. Those works had been commissioned by Apponyi in 1793 and published in London in 1795 and 1796, just when Beethoven was publishing his first trios and piano sonatas. Writing a string quartet, he would have felt even more keenly, as John Keats put it, the high cliff of tradition towering above him. To heighten the inevitable competition with Haydn, the commission for Beethoven’s first six quartets actually came in the fall of 1798 from Prince Lobkowitz, who also asked Haydn at the same time for another new set of six. But Haydn, now aging, was able to produce only two, the pair of Opus 77, followed by the unfinished Opus 103 a few years later.

Beethoven began work on his own quartets in 1798. After massive preparatory work and extensive revisions, they were ready for publication in two sets of three in June and October 1801. Aside from No. 4 in C minor, the order of composition, to judge from the sketchbooks, was: No. 3 in D major, No. 1 in F major, No. 2 in G major, No. 5 in A major, and No. 6 in B-flat. The C Minor, No. 4, remains the orphan of this group, and because we have no sketches for it in the surviving sketchbooks, some believe that it might go back to Bonn antecedents and might have been written much earlier than the others.25 But there is no positive basis for this assumption, and all the anecdotal remarks denigrating the quartet come from later and not trustworthy observers. The only story that rings true comes from Ries, who reports that he asked Beethoven about a contrapuntal passage in No. 4 that he thought violated traditional procedures, to which Beethoven replied, “I allow them.”26

The odds are good that the C Minor Quartet was written at about the same time as the others of Opus 18, but for some reason simply not worked out within the sketchbooks he was then using. He may have worked on it in a hypothetical lost sketchbook of 1799–1800, or on separate sketch leaves that are now lost.27 It has, after all, substantial affinities with other C-minor works of this time; the first and last movements, especially, evoke the comparable movements in the “Pathétique,” written just before work on the quartets began. The clever and intricate Andante scherzoso bears some resemblance to the slow movement of the First Symphony, though the quartet Andante is of finer workmanship.

The most imposing quartet of Opus 18 is No. 1, one of Beethoven’s longest four-movement cycles before the Eroica. The material in the first movement is characterized by a short, memorable motif, recognizable from its rhythmic form alone. Except where the second group in the dominant provides relief through smoothly flowing eighth notes, the motif serves as the leading factor throughout. But this primary motif, though always well defined, appears in many guises. Sometimes its pitches are entirely different; sometimes it acts as accompaniment to other thematic figures; sometimes it lacks its first note but, like a puzzle in a Gestalt formation, is still recognizable.

String Quartet Opus 18 No. 1, first movement, beginning, violin I only:

The first Allegro is thus an early instance of an amply developed movement that is permeated by a single motif, anticipating the Fifth Symphony, by far the most famous Beethovenian example (*W 15a). The main motif can either be heard as if it were a picaresque figure in a narrative, which enters into varied situations and encounters, yet maintains its own form; or else as if it were a recurrent emblematic figure that runs like a red thread through an entire complex tapestry. The sketches show that it began life in 4/4 time and was then transformed into its characteristic triple meter (*W 15b).

A window onto the genesis of this quartet is provided not only by its extensive sketches but also by the chance survival of a complete early version of the entire work.28 Beethoven gave this version to his old friend Karl Amenda, who preserved it among his papers after receiving a letter from Beethoven telling him not to circulate it because he had now revised the entire composition, “having now learned how to write quartets.”29 The two versions are instructive, both for their contrasts and as an example of Bee-thoven’s not only sketching but working through to complete drafts of works in early versions, few of which survive. In the second version we see Beethoven, especially in the first and last movements, tightening the content, improving the voice leading, and making the string writing more idiomatic—in all, he gave the work the mature profile and idiomaticity that he now saw was essential to a higher level of quartet writing. That sketching and revising the Opus 18 quartets cost Beethoven intense effort does not in principle distinguish them from many of his other works, but it confirms the exceptionally high standards he associated with this genre.

Striking in Opus 18 No. 1 are the fugal passages in the first and last movements. Fugue is more characteristic of the quartet than of the piano sonata. It remained a mark of the more developed, intellectual character of quartet composition, in which composers were expected to show off their contrapuntal accomplishments both in creating interesting inner and lower parts and in the learned disciplines of fugue and fugato, even when used as episodes within sonata-form or sonata-rondo structures.30 The same prominent use of fugal textures appears in other works that Beethoven regarded as truly serious, lofty accomplishments, such as the Third, Fifth, Seventh, and Ninth symphonies. In each of these major orchestral works, all of epic character, fugue or fugato occurs in at least one movement, sometimes more, typically as a way of extending the developmental range by treating one or more themes contrapuntally. And although we find no fugal episodes in the even-numbered symphonies and in most of the piano sonatas before the late period, this lack in no way lessens the quality of those works but simply signals that their aesthetic models make no room for fugal development and proceed in other ways; the Fourth Symphony is a prime example.

Celebrated for expressivity is the slow movement of Opus 18 No. 1, known also for its associations with the tomb scene from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. These connections arise from remarks that appear in French at particular places in the sketches near the end of the movement: for example, “il prend le tombeau” (“he comes to the tomb”) followed by “désespoir”(“despair”) —the word is hard to decipher; “il se tue” (“he kills himself”); and “les derniers soupirs” (“the last sighs”) (*W 16). The final remark is attached to a closing segment for the movement and uses a traditional “sigh” motif. Beethoven often wrote in Italian or French in his sketchbooks when he was thinking out passages and, at times, larger plans for movements or works.31 The association with Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is also supported by other evidence: Amenda recalled telling Beethoven that this movement induced thoughts about the separation of two lovers, to which Beethoven is said to have replied, “[For this movement] I was thinking of the burial vault scene in Romeo and Juliet.”32

The large-scale sonata form of this Adagio gives it a weight and gravity beyond all but a few of Beethoven’s earlier slow movements. If Beethoven was thinking of Romeo and Juliet, then the main theme, in D minor, and the principal second theme, in F major, may represent the two conflicting principles of Romeo’s despair and Juliet’s beauty. If the burial vault scene from the play was a generating idea for the movement, as it may have been, the important point is that Beethoven, not wanting to be literal, destroyed all traces of any such program in the finished work. What evidence he left exists only by chance in the sketches, which he never expected the world to know. Essential in the movement is the expressive conflict of these two basic musical ideas. Oppositions between paired and contrasted themes, gestures, motifs, and segments always with clear-cut rhythmic profiles—become a vital means by which Beethoven generates drama, action, and larger shape in his sonata-form movements, increasingly so as he moves from early to middle-period works.

The other quartets of Opus 18 offer varied perspectives on Beethoven’s hard-won virtuosity as a quartet composer. Thanks to Amenda, we know about his revision of No. 1, which has in fact been published and recorded. He also revised No. 2 and possibly No. 3.33 Quartet No. 2 is built along different lines from No. 1. It is light and graceful, and has an elaborated slow movement that alternates Adagio and Allegro segments, perhaps following a Haydn model, and anticipating the tempo alternations in La Malinconia, the finale of No. 6. No. 2 is the epitome of the charming, not the forceful, as different from No. 1 as it can be. In Beethoven’s first sketchbook, in which he worked out Opus 18 No. 3, the first of the set to be composed, he entered the annotation “le seconde quatuor dans une style bien legère excepté le dernier” (“the second quartet in a light style, except its finale”).34

No. 3, striking out in other directions, prizes legato linear motion in its first movement beyond all else. In the opening phrase, after a solo upward seventh leap, the first violin moves down in graduated phases, alternating smooth eighth-note figuration with long points of arrival, falling a ninth from high G to lower F![]() . The undulating motion of the material in the third measure and its many ramifications recall Mozart more than Haydn; sure enough, in the course of the movement, we find possibly unconscious reminiscences from the finale of Mozart’s A Major Quartet, K. 464, which we know Beethoven copied. The pace and flow of this movement is also akin to that of the “Spring” Sonata, Opus 24, in which a similar ebb and flow of melodic lines is the primary feature of the first movement.

. The undulating motion of the material in the third measure and its many ramifications recall Mozart more than Haydn; sure enough, in the course of the movement, we find possibly unconscious reminiscences from the finale of Mozart’s A Major Quartet, K. 464, which we know Beethoven copied. The pace and flow of this movement is also akin to that of the “Spring” Sonata, Opus 24, in which a similar ebb and flow of melodic lines is the primary feature of the first movement.

No. 5 is often taken as the main inheritor of Mozart’s K. 464, because it shares with Mozart’s quartet its key, its movement plan (with the Menuetto second), its position in the cycle of six quartets, and certain other features. Actually, though, it is quite independent of the Mozart work if we look below the surface, as it omits all the characteristic structural underpinning of the Mozart quartet, namely its use of descending-third chains in both first and last movements.35

The cycle closes with the Quartet No. 6, a small-scale, compact, intimate work of high craftsmanship. With its opening in a Haydnesque texture, the first movement unfurls a main theme that contains a “folded arpeggio,” that is, a theme in which the notes of the tonic chord are presented in this order: 1–5–3–1–5–3–1. But instead of moving downward, as this sequence of figures implies, the notes zigzag upward, alternating small-scale up-and-down motions to form a theme (*W 17). Beethoven employs this means of thematic formation in later works as well. The whole first movement of No. 6 makes witty use of the turn figure on the fourth beat, as we could expect. It also finds room for rolling, questioning phrases, as in the preparation for the recapitulation, where a dying away leads to a measure of silence and then a pianissimo pause on the dominant.

The Adagio ranks with the most expressive of the early slow movements, yet harbors surprises, as when a sudden fortissimo erupts in the reprise, disclosing powerful feelings that had been hidden below the lyrical surface. The Scherzo is a tour de force of syncopation, like no other early Beethoven movement, an explosion of rhythmic eccentricity after the more nearly straightforward rhythmic patterns of the first two movements. But the crux of the whole work is its finale, labeled La Malinconia. The movement comprises four sections: (1) Adagio; (2) Allegretto quasi Allegro; (3) a return of (2), preceded by brief returns of Sections 1, 2, and 1; and (4) Prestissimo (preceded by a brief Poco adagio). In Section 3 Beethoven plays out returns of previously heard contrasting material, each return shorter than the one before. The sense is that of indecision as to what will happen to these opposed emotional states—the melancholic and the sanguine—and how their opposition can be resolved. The question is then settled and the movement stabilized by the Allegretto, which now returns in Section 4 and finds its way back to the tonic. The movement ends in a manic close taken at the fastest tempo marking found in Beethoven’s works.

What does the title La Malinconia mean? A partial clue is found in the special performance direction, which recalls the “Moonlight” sonata: “Questo pezzo si deve trattare colla più gran delicatezza” (“This piece is to be played with the greatest possible delicacy”), which means that Beethoven wants the strongest shades of light and darkness in the phrasing and dynamics. The words La Malinconia have traditionally been taken to refer only to the Adagio, as a representation of melancholia, reflecting Beethoven’s personal depression as his deafness increased.36 The long Adagio gropes through darkness, beginning with the bare outlines of periodic structure in its rhythm and phrase organization which is then undercut by sudden contrasts of high and low chords, pianissimo and fortissimo (*W 18). The Adagio then gradually loses its original rhythmic profile as it wanders through distant harmonic regions. Finally it clings to the figure of a strong quarter note preceded by a sixteenth-note-triplet turning-motion upbeat in its last measures, again alternating forte and piano. In its last phrase the slow crescendo from pianissimo to fortissimo is held together by the cello while the other strings rise through a succession of chromatic harmonies, searching for a harmonic foothold but not finding it until they reach the final dominant.

But another way of looking at La Malinconia, which might have roots in both the deafness crisis and in the idea of representing two temperaments, two states of the soul in melancholia and sanguinity, is to see it as a bold extension of the programmatic into the string quartet, a genre it had not penetrated before. Beethoven’s use of this title, with all its implications, is a departure from Haydn and Mozart, and it goes beyond his reticence regarding the Romeo and Juliet allusion in the first quartet. Haydn and Mozart never used representational titles in their quartets even when they might conceivably have been appropriate. Certainly in some of Haydn’s and Mozart’s quartets, strongly profiled and virtually nameable emotional states stand right at the border of consciousness—of the performer, of the listener, and probably of the composer. We need only think of Haydn’s profound slow movement of Opus 76 No. 5 or the introduction to Mozart’s “Dissonant” Quartet, K. 465, the strangest harmonic experiment in all of Mozart’s chamber music. That Beethoven could have had the “Dissonant” Quartet in mind, directly or as distant recollection, as a potential background to La Malinconia may seem at first far fetched. But in fact the affinities between this slow introduction and the modulatory scheme of the finale of K. 465 are real, though generally unrecognized.37 At all events, this movement rises like a great peak out of the postclassical landscape of the Opus 18. It foreshadows the wider emotional world that Beethoven would explore several years later in the Opus 59 trilogy, by which time composing string quartets had taken on for him a greatly enlarged range of meanings.