![]()

Except for the deafness crisis, no period in Beethoven’s life has aroused more speculation than the years from 1813 to 1817, the lengthy twilight zone between his second and third maturities. The basic facts compel us to see this period as a major break in the larger continuity of his career, a time of psychological distress and of diminished creative energy after the extraordinary ten years that had culminated in 1812 with the Seventh and Eighth Symphonies. But it is far more fruitful to focus less on what was ending, and more on what was beginning; less on his loss of productivity and more on the progressive features of the few significant works that he completed. Once again we face the underlying question of how we can relate Beethoven’s personal life to his artistic evolution and how we should construe this phase of his development—whether primarily as a lapse or as a period of quiet gestation in which the late style slowly emerges. Without denying that much depends on one’s angle of vision, I will argue for the positive side of the question.

First, a few words on the main biographical developments. Beethoven’s chronic physical ailments became aggravated in 1812, and his physician ordered him to seek cures at Teplitz, Karlsbad, and Franzensbrunn.1 His deafness was growing progressively worse, intensifying his isolation and hardening the barriers that hindered social communication. July 1812 at Teplitz was the time of his passionate letter to his “Immortal Beloved,” with all its implications for his acceptance of loneliness, abandonment of any lasting relationship with a woman, and withdrawal further into the self. His family obsessions broke out again, now in the form of a quixotic journey to Linz in October 1812 for the express purpose of interfering with his brother Johann’s current affair with his housekeeper, Therese Obermayer. Beethoven’s zealous involvement with family members was soon to take on an even more extreme form over the guardianship of his nephew, which began in a legal sense in November 1815 when his brother Carl, one day before his death, made his will appointing Beethoven and Carl’s wife Johanna as coguardians of their son Karl.

Then there is Beethoven’s private Tagebuch (diary) covering 1812–18, the most vivid testimony of his deepening isolation in these years. As Maynard Solomon wisely observed, Beethoven began keeping the Tagebuch just at the time when he was becoming estranged from many of his former close friends, such as Gleichenstein, Breuning, Erdödy, and others, and was now confiding his innermost feelings to the pages of his diary.2 Finally, there was the crushing truth that his personal financial situation had taken a serious blow from the Austrian Finanz-patent, that is, the national currency devaluation of March 1811, which drastically reduced the value of his annuity. Compounding the bad economic news were the sudden death of his patron Prince Kinsky in November 1812 and the bankruptcy of Prince Lobkowitz, causing drastic losses in support that were only partly remedied by Archduke Rudolph’s generosity.3 It seems very clear that Beethoven was moved by genuine financial concerns as well as career ambitions in his quest for popular success in these years.4

In the outer world dramatic changes were unfolding. Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in June of 1812, with “the largest army ever assembled by any one force in European history,”5 ended in disaster three months later at Borodino. The miserable retreat of the beaten French armies from Moscow over the four months from October 1812 to January 1813, followed by Napoleon’s desperate campaign in Saxony that spring and his defeat by Wellington in Spain at Vittoria in June, ended his dreams of sustaining his empire and aroused the hopes of his ill-assorted enemies that they might finish him off at last. In April 1814 he was forced to abdicate and was exiled to Elba, off the Tuscan coast, precipitating the first massive turn of the great diplomatic wheel by which the Great Powers—England, Russia, Austria, and Prussia—now readied themselves to reconstruct the old European system and set up a new balance of power that could prevent any threats to the restored or strengthened monarchies.

The result was the Congress of Vienna. Planned to begin in August 1814, it actually opened in September and met until June 1815, its last phase coinciding with Napoleon’s electrifying escape from Elba, the “Hundred Days,” and his final defeat at Waterloo, June 16–18, 1815. The Congress brought a swarm of high diplomats and royalty to Vienna, including Czar Alexander I, King Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia, and an array of titled aristocrats and their entourages. Amid glittering receptions, balls, and entertainments, Beethoven, as the most famous of Viennese composers, could draw on the backing of some of his aristocratic patrons, particularly the archduke, and play a visible role. In effect the Viennese cultural managers could show him off to visiting ambassadors and aristocrats as one of the brightest stars of Austrian artistic life, perhaps its brightest one. In 1814 Count Razumovsky and the archduke presented him to visiting royalty and others, and although Beethoven showed his customary intolerance for the pompous social life of the nobility, he let himself be persuaded to play at a concert in January 1815 in the Rittersaal. There he accompanied Franz Wild in one of his songs and presented the spellbinding first-act quartet from Fidelio.6 Even though most of the gathered nobility preferred ballroom music to Beethoven, his reputation was by now so great that he could easily become the musical hero of the Congress. Despite his habitual protests, he shamelessly cultivated this role by hurriedly composing the bombastic cantata Der Glorreiche Augenblick (“The Glorious Moment”) for the assembled heads of state, along with a flashy polonaise for piano for the czarina Elisabetha Alexievna, “Empress of all the Russias,” as the title page proclaimed when it came out very soon thereafter as his Opus 89.

Taking a longer view of these years, we have to reckon with a loss of his earlier productive momentum beginning in the winter of 1812–13. Although his decline in productivity had strong inner motivations, it is curious that it coincided with the collapse of Napoleon’s dreams of empire, almost as if Beethoven’s conquering and heroic works of the second period might in some way have been unconsciously and symbiotically linked to the military conquests that marked Napoleon’s career during these same years. We remember that Beethoven, in 1806, had remarked after Napoleon’s victory at Jena that if only he understood war as well as he understood music, he could conquer the great general.

After all, in nine years he had written, along with other major works, eight symphonies that had completely revolutionized the genre, and he had enlarged the expressive capacities of instrumental music in ways that even his most admiring contemporaries had not predicted. It has been argued that Beethoven was suffering from creative exhaustion and stasis during this period, 1813–17, as if the energy of the previous years had badly faded and was not yet ready to be refired. If we measure by sheer productivity this is a reasonable hypothesis, but if we look more sharply at the works of the later second period, between 1809 and 1812, we find unmistakable features that foreshadow some aspects of the late style. Among them are the harmonic anomalies of the Lebewohl Sonata, Opus 81a; the motivic concentration, compression, and angularity of the first movement of Opus 95; and even the surface lyricism hiding complexity that we find in Opus 96.

When we think of the popular and trivial compositions that Beethoven wrote in this fallow period we should recall that even in earlier years he had always saved some energy for accessible works that he could publish for profit, enabling him not only to dominate the musical scene with higher achievements but also to woo the public with compositions that would sell and keep him popular—simpler works that were ingratiating and easy to perform. Sometimes, paradoxically, these were modest essays in the same genres in which he was working out compositions on the grand scale. An example is the set of three Marches for Piano Four Hands, Opus 45, which Beethoven completed sketching in the Eroica Sketchbook, actually taking time off to compose them while he was in the thick of work on the Funeral March in the Eroica. For years he kept up the habit of spinning off minor works while in the heat of producing major ones. Thus in 1805 he published the two “easy” Piano Sonatinas Opus 49, works he had sketched ten years earlier; in 1806, the trio for two oboes and English horn, Opus 87, of the same vintage as the sonatinas; in 1810 the wind sextets Opus 71 and Opus 81b, dating from the mid-1790s. Apologizing to Breitkopf for offering him the sextet to publish, he had written that it was “one of my earlier works, written in one night, and one can only say that it is written by an author who has brought out at least some better works.”7 Even in the last years he would rummage among his papers for salable earlier works, as we see from his refurbishing the “Kakadu” Variations in 1824 and his exhumation of the song “Der Kuss,” of 1798, which he published as Opus 128 in 1825.8

If we look more closely at Beethoven’s actual productivity in the “fallow” period, we can distinguish several types of projects. First we find artistically insignificant works written to make money or to restore and build his broad public reputation; the two most prominent are Wellingtons Sieg and the cantata Der Glorreiche Augenblick. Then there were stylistically retrospective works that look back at second-period achievements. The biggest such project was the difficult job of reconstructing Leonore as Fidelio, but there were unfinished works that show the same style features, including the torso of what would have been a sixth piano concerto and his futile attempt at an F-minor piano trio, both in 1815. Waiting for publication in these years were a series of important compositions that had been written by 1812 but were not to be published until 1816, among them the second setting of “An die Hoffnung,” the Quartet Opus 95, the “Archduke” Trio, the Violin Sonata Opus 96, and the Seventh Symphony. Finally, and most important, were the few prophetic, fully realized, and highly expressive compositions, all written between 1814 and 1816, that embodied his full creative powers: the Piano Sonata Opus 90 in E minor, the two Cello Sonatas of Opus 102, the song cycle An die ferne Geliebte, and the Piano Sonata Opus 101 in A major.

Celebrating Wellington’s Victory

We need hardly be reminded that the battle piece Wellingtons Sieg, (“Wellington’s Victory”) is far below Beethoven’s normal standards, a shameless concession to the political wave of the moment, written to win him acclaim as a patriotic Austrian artist. He wrote it at the request of Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, “Court Mechanician” for the Austrian royalty, an ingenious inventor of mechanical devices of all sorts, including the metronome, with which his name became permanently associated. Besides devising a mechanical trumpeter that played a French cavalry march with a piano accompaniment, Mälzel rigged up a new device, called the Panharmonicon, that combined military band instruments and a bellows in a case, with keys linked to pins on a revolving cylinder, as in a barrel organ or music box. Mälzel started out by producing cylinders for Cherubini’s Lodoïska Overture, Haydn’s “Military” Symphony, and a Handel chorus, but he thought he would really make a hit with the public if he persuaded Beethoven to write a patriotic battle piece for his new machine. There were already battle pieces galore in the orchestral, military band, and piano repertoires of the time, such as Georg-Friedrich Fuchs’s band piece Bataille de Gemappes or Louis Emmanuel Jadin’s piano piece La grande bataille d’Austerlitz of 1806, composed to celebrate Napoleon’s victory. Daniel Steibelt, a composer of some reputation and sometime rival of Beethoven’s as pianist, had composed a piano fantasy called The Burning of Moscow for Napoleon’s entry into Moscow in 1812, and many more such works were being produced for an avid public.9

Beethoven gave in to Mälzel’s blandishments and concocted his piece in two parts. Part 1 depicts the battle itself, beginning with “Rule Britannia” to represent the British forces and continuing with “Malbrouck,” or “Marlborough,” as the French army’s march, both preceded by trumpets and drums. The battle itself is a colossal noisemaker with cannon shots for both sides marked in the score and a weakened “Marlborough” signaling the French in defeat. Part 2 consists of a “Victory Symphony” in several parts, including a new march and the melody of “God Save the King” as theme with two variations, one a tempo di menuetto, the other a fugato that leads to a smashing final coda. Ignaz Moscheles, an eyewitness, later reported apologetically that Beethoven had taken this whole plan from Mälzel, and “even the unhappy idea of converting the melody of ‘God save the King’ into a subject of a fugue in quick movement, emanates from Mälzel.”10

The piece never materialized on the Panharmonicon, however, since Beethoven decided to orchestrate the work and agreed to produce it at a public concert in 1813, at which he and Mälzel would share the limelight. The program turned out to comprise the premiere of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, two marches (by Dussek and Pleyel) played by Mälzel’s mechanical trumpeter, and Wellingtons Sieg as the final number. The orchestra members included the best performers in Vienna, including Schuppanzigh as concertmaster, Salieri conducting the drummers and cannoneers, Ludwig Spohr, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Joseph Mayseder, the famous double-bass virtuoso Domenico Dragonetti, and even the young Giacomo Meyerbeer. Everyone understood that the piece was nothing more than a patriotic extravaganza, not a serious composition, but Beethoven’s involvement clearly embarrassed his more sophisticated admirers. For example, Wenzel Tomaschek declared that, as he understood it, Beethoven himself “declared the work to be folly and that he liked it only because with it he had thoroughly thrashed the Viennese.” Thayer evaded any real evaluation of the work by calling it “a gigantic professional frolic.”11

Although it is possible to see Wellingtons Sieg as a “monument of trivialities” or as representing Beethoven as a “pioneer of kitsch,” that is only part of the story.12 By agreeing to devise the piece and then perform it at a major concert, Beethoven was obviously riding the euphoric wave that swept over Vienna after Napoleon’s recent defeats and that seemed to promise a new era of political recovery after years of oppression and defeat. To write and produce the work at one or two major public concerts was to indulge in sincere patriotic celebration. But to then go further and publish the work, moreover to give it an opus number and place it in the series of his important compositions, showed that his deep yearning for public recognition and financial security had gone beyond any earlier limits and that his need for public acclaim, not just in the world at large or in the future but then and there, in Vienna and in his lifetime, for once overrode his normal standards of self-criticism. About Wellingtons Sieg he could have said the opposite of what he had told Radicati about the Opus 59 Quartets, namely that they were not for a later age but only to be patriotic, to capitalize on current national feeling, and to make money.

The cantata for the Congress, Der Glorreiche Augenblick (“The Glorious Moment”), published posthumously in 1836 as Opus 136, is, like Wellingtons Sieg, a grotesque parody of his serious style, a plodding fabrication that falls far short of what he had achieved long ago with his youthful cantatas for Joseph II and Leopold II. The text was written by Alois Weissenbach, a Tyrolean physician and poet who came to Vienna in September 1814, met Beethoven, and persuaded him to collaborate on what has been accurately described as this “rather bombastic” piece.13 Beethoven may have felt a special sympathy for this project since Weissenbach was also deaf and, if we can believe the poet’s memoirs, spent considerable stretches of time with Beethoven discussing their mutual affliction.14 The cantata, for four solo voices, chorus, and orchestra, shows a few faint sparks in its solo numbers that are immediately extinguished by its utterly banal choruses.15 A couple of passages for solo violin and solo cello were no doubt written to arouse the interest of the first-desk players (probably Schuppanzigh and Joseph Linke), but they fail to sustain the work. To compare this patriotic sycophantry with the true beauty of another cantata Beethoven was writing in 1814–15—his setting of Goethe’s Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage for four voices and orchestra—is to see the difference between his tossing off a casual simulation and his thinking through and carefully shaping a setting of poetry that meant something to him.

The current view in modern criticism is that the success of Fidelio in 1814 prompted Beethoven’s acceptance of a sudden new role as a famous composer in the heightened political atmosphere that was rising out of Napoleon’s downfall. But there was more to it. Well aware that he was producing works such as the cantata and Battle Symphony that were designed for nothing but public success, Beethoven took considerable trouble to assuage his conscience and obliquely explain to his admirers what he was up to, even to do so publicly. He defended his writing such works by inserting a public statement about Fidelio in the Friedensblätter in July 1814. He may, of course, have done so to drum up business for the revival of the opera during the summer lull, but the defensive tone of the message, and its other implications, above all of his self-conscious public status, are clear enough:

A Word to His Admirers

How often, in your anger that his depth was not sufficiently appreciated, have you said that van Beethoven composes only for posterity! You have, no doubt, now retracted your error, even if only since the general enthusiasm aroused by his immortal opera Fidelio, in the conviction that what is truly great and beautiful finds kindred souls and sympathetic hearts in the present without withholding in the slightest the just privileges of posterity.16

That he bothered to publish such a statement at all tells the story.

To find a better way of understanding how Beethoven came through this period, we can focus on his more important projects, beginning with the Fidelio revision in the early months of 1814, then the line of works that run from Opus 90 to Opus 101. Recent discussions of the 1814 Fidelio have stressed its glorification of Don Fernando as a benevolent ruler whose noble and enlightened gestures at the end reflect the supposedly benign qualities of the European heads of state who were triumphing at last over Napoleon.17 In more strictly musical terms the alterations reveal Beethoven thinking very differently about operatic material than he had eight years earlier. This new version shows a tightening of the discourse, much removal of repetitions, splicing of adjacent phrase units to move the action forward, and sharpening of contrasts. Quite apart from the new dramatic focus, the compositional changes point in the direction of his later style. Thus the new overture in E major solves the earlier problem he had faced in the three C-major overtures of how to anticipate Florestan’s aria of hope for salvation. Here the answer is drastic: he leaves it out, writing an overture in which the spirit but not the material of the opera comes through in a vigorous and strongly dramatic piece of orchestral writing.

The result is that the 1814 Fidelio is a hybrid that combines musical material of two distinct periods, which is why he said that revising this work was so much more difficult than composing a new one.18 While the later version strengthens the role of Leonore, it also strengthens the figure of Florestan in his representation of heroism as endurance. As we saw earlier, the great scene in the dungeon, instead of ending with Florestan’s sinking back in exhaustion after dreaming of release, has a new coda in which he sees a vision of his “angel Leonore” as agent of salvation. The revision thus provides a link to Beethoven’s physical and psychic struggles at the time, during which he repeatedly exhorted himself to stoic acceptance of his own limitations and the hard fate that his artistic commitment was forcing on him.19 As he wrote in his Tagebuch in 1813, copying from Herder: “Lerne schweigen, O Freund” (“Learn to keep silent, O friend”).20

The 1814 Fidelio constitutes a laboratory for transforming his style at the level of phrase organization and operatic formal structure. At the same time its emphasis on the lyrical—in solo and ensemble numbers above all—furnishes another basis on which Beethoven could work toward reformulating his instrumental style. To do so he turned as soon as possible to the piano sonata.

The first result is the E-minor/major Sonata Opus 90, whose autograph is dated August 16, 1814. This is the first instrumental work that Beethoven wrote after the Fidelio revision—as if he gave himself a welcome gift, after his operatic labors, of returning to the most familiar and comfortable of his musical domains. The movement headings, which for the first time are in German, do not use the traditional tempo designations, even in translation, but instead convey character.21 Thus the first movement, in E minor, is headed, “Mit Lebhaftigkeit und durchaus mit Empfindung und Ausdruck” (“With liveliness and throughout with feeling and expression”); the second is headed, “Nicht zu geschwind und sehr singbar vorgetragen” (“Not too quickly and to be performed in a very singing manner”). The pianist and scholar Charles Rosen describes the first movement as “despairing and impassioned, laconic almost to the point of reticence.”22 A special feature is its weak initial tonic, E minor, moving at once to its relative major, G major, and on through a lyrical counterstatement to its first cadence. We then encounter a sudden, striking use of high and low registers within a single phrase, a definite sign of Beethoven’s late style, which is marked by discontinuities of register in unexpected ways that do not correspond with phrase endings or beginnings. Remarkably, this figure maintains its extremely strong registral contrasts not only at the recapitulation but also at the very end of the movement (*W 44).23

The second movement, perhaps Beethoven’s longest singing rondo, reveals his renewed capacity for sustained emotional intimacy; as Tovey said, it is “devoted to the utmost luxuriance of lyric melodies.”24 Among other movements in Beethoven’s middle- and later-period works committed to “absolute melody,” this is the one most fully given over to a long-phrased, symmetrically structured line that is seductively “cantabile” (singbar) from beginning to end, in which the contrasting episodes match the spirit of the main melody and in no way ruffle the surface or mar the effect of its many repetitions. This movement might reflect a carryover into the keyboard sonata of the major-mode lyric intensity of some parts of Fidelio—above all Leonore’s aria “Komm, Hoffnung,” which is also in E major. In the same vein we might hear the opening of the C Major Cello Sonata, Opus 102 No. 1, with its cello solo marked by the terms “teneramente” (sensitively) and “cantabile,” as a reflection of the voice quality, as well as the range and style of Florestan’s “In des Lebens Frühlingstagen” (“In the spring days of life”).25 The same terms are used here in the second movement of this piano sonata, “teneramente” being the marking for each return of the main theme after the contrasting episodes. Another sign of Beethoven’s intense exploration of melody in these years, the song cycle An die ferne Geliebte, was written in very close proximity to Opus 102.26

The two cello sonatas of Opus 102 reflect other dimensions of the emerging late style, set up as they are as correlative opposites. In No. 2 we find the concise, abrupt, brilliant discontinuities of its first movement balanced by the dark hymnlike slow movement and the bristling fugato finale. In the C-major Sonata, No. 1, Beethoven returns to his familiar formal plan of a sonata “quasi una fantasia” that brings a modified restatement of the opening Andante just before the finale, as in Piano Sonata Opus 27 No. 1. Everywhere in the C Major Cello Sonata he focuses on the linear flow and contrapuntal integrity of the material, whether the character is romantic (as in the slower movements), vigorous and boisterous (as in the A-minor Allegro), or humorous and ironic (as in the Finale). Contemporaries were baffled; the Mannheim Hofkapellmeister Michael Frey, who heard Czerny and Linke play the premiere of one of these sonatas, wrote in his diary, “It is so original that no one can understand it on first hearing.”27

An die ferne Geliebte (“To the Distant Beloved”), which stands alone as Beethoven’s only song cycle and his only song composition on the scale of his instrumental works, is a basic step in the direction of his oncoming new style. The text is by a Viennese Jewish medical student named Alois Jeitteles. It was probably written for Beethoven and does not seem to have an existence apart from this setting.

The full text consists of six poems of differing meters in which the poet, far from his beloved, sings of desolation and loneliness. In the first song he sits on a hill “in the blue land of clouds” and mourns that his beloved cannot hear his sighs and yearnings, while the later stanzas offer images of nature that surround the poet in his misery—“the blue mountain,” sun and clouds, the valley below, the wind softly blowing, the running brooks. And in the final poem, which seized the imagination of the Romantics, above all Schumann, comes the climactic strophe:

| Nimm sie hin denn diese Lieder, | Take, then, these songs |

| Die ich dir, Geliebte, sang. | that I, beloved, sang to you. |

| Singe sie dann Abends wieder | Sing them of evenings |

| Zu der Laute stiller Klang. | to the quiet sound of the lute. |

This verse is followed by three more strophes of the same type. The joining of these songs in a single narrative inaugurates the song cycle, which Schubert was within a few years of perfecting in Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise. Beethoven’s careful modeling of phrase and word to music and his concern to give the whole a sense of unity as a complex sequence of feelings in a progressive emotional and structural totality makes this work a turning point in the development of the German art song. That it coincides with a new phase in Beethoven’s life situation—one of personal crisis that was giving way to resignation and to a new productive stage—is suggested more by its expressive directness than by any highly elaborated musical complexity, for which there would not have been room in the genre of the German lied.

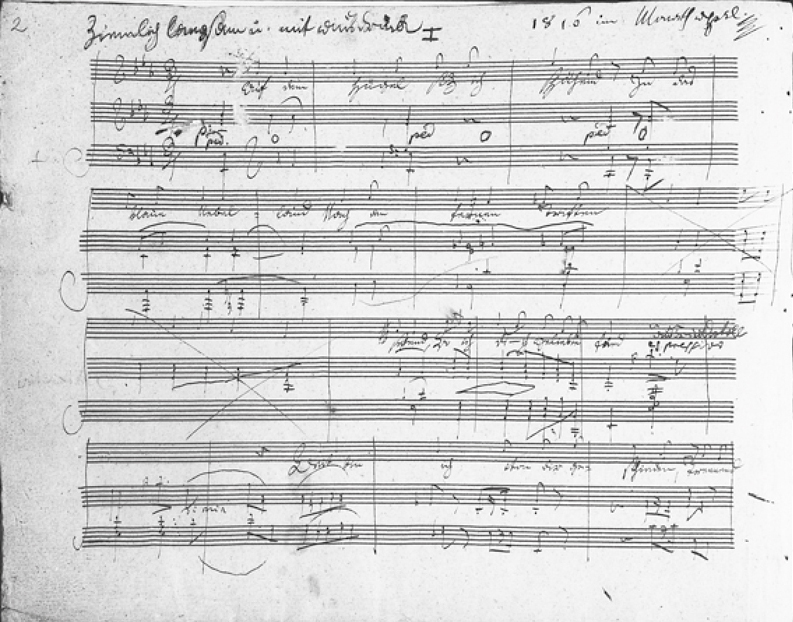

The first page of Beethoven’s autograph of his only song cycle, An die ferne Geliebte (“To the Distant Beloved”). (Beethoven-Haus, Bonn)

At one point Jeitteles’s poem sounds a strange note:

| Denn vor Liebesklang entweichet | For at the sound of love’s singing |

| Jeder Raum und jede Zeit. | all space and time vanishes. |

The new sense of space and time that will be embodied in the late style is distantly announced in these verses, as if the poet had somehow provided Beethoven with a poetic image of the timeless forms of expression, the otherworldliness, for which his new music had already begun to strive. It is notable as well that in his Tagebuch of these years Beethoven occasionally copied passages from Eastern religious tracts that referred to the timelessness of mystical experience.28

The late style in all its fullness comes forth in the Piano Sonata Opus 101, one of Beethoven’s greatest compositions in any genre. Using the cyclic return form of Opus 102 No. 1, written a year earlier, Beethoven crosses the border into a new aesthetic territory, entering a sound world whose philosophical depth is new in his work and rare in music of any age. Here the contrasts between movements are substantial but less jagged than in the cello sonatas, and the whole work belongs to a sphere of intimacy beyond even his most expressive earlier piano sonatas. This sonata strikes us as being far bigger than its medium and encompassing a world in itself, thus conveying a quality that pervades the late works.

The form of the first movement, in A major, is enigmatic. It falls into a large-scale two-part framework in which the first part contains the equivalent of the exposition and development, and the second part presents the recapitulation and a short coda. But many of the traditional form-building features associated with sonata form in more traditional terms are left deliberately indistinct. These features, such as the traditionally clear division between first and second theme in an exposition, or between exposition and development—even between development and recapitulation—are disguised and elided, and are given no special emphasis. Instead they glide by without being noticed by the casual listener. A pensive, Romantic, quasi-improvisatory feeling pervades the whole of the first movement, which flows from beginning to end and, as Beethoven wrote in his tempo heading, is to be played with “the innermost expressiveness.” The beginning of the movement, with its first phrase on the dominant chord, poses a question, and it implies an eventual answer. That answer might be a firm arrival on the tonic chord, but no such arrival with tonic A in the bass takes place until three-quarters of the movement has been traversed.

The remaining movements offer transcendent representations of familiar movement types. Thus the Scherzo is a fantastic march in F major with persistent imitative dialogue between high and low voices. The Trio intensifies this dialogue, the voices following each other in close canonic imitation. Then the pensive slow movement, followed by the recall of the opening of the first movement, gives way to a vigorous and energetic finale that displays further imitative dialogue and a fugal middle section. A particularly sensitive appraisal of this remarkable sonata points out that “the sheer joy of exercising a faculty that is art and craft, an intellectual activity, an emotional release, and a unique means of communicating . . . is all to be found in this sonata . . . the most physically euphoric of the last five.”29

To judge Beethoven’s productivity in this period simply by counting works and comparing totals with those achieved in the great years of his second maturity is to miss the point. It is perfectly true that between 1813 and late 1817, when he began work on the Hammerklavier Sonata, he had no symphonic project in hand and was far less prolific than he had been in the middle and late-middle years up to 1812. But along with the personal factors, what accounts for this change is his evolution toward the transcendental that is revealed by these works—the Piano Sonata Opus 90; the cello sonatas of Opus 102, An die ferne Geliebte; and the Piano Sonata Opus 101. Accordingly, what has been seen as a “fallow” period might be reconceived as a period of self-reconstruction, a necessary questioning of previous approaches and the gestation of new ones, in which a new composing personality within him was in process of emerging.

Meanwhile, the weaker works of this time—Wellingtons Sieg and the Congress cantata—were products of Beethoven’s own ambivalence, born out of financial necessity, desire for fame, and a debilitated defense of conscience. They should be set aside as negligible byproducts, not as works in the main line.

The higher artist in Beethoven in these supposedly arid years was not dormant but, as he aged and gained deeper experience, was quietly reshaping his ways. As part of this process he reduced his reliance on the powerful, the dynamic, the developmental, and the rhetorical. Listening to the voices within himself, he yielded primarily to what was deeply personal and inward. At the same time, he began to move toward combining the melodic and contrapuntal dimensions of his thinking in a new synthesis that would enable him to come to terms with Bach. He was working toward a higher level of musical integration that would nevertheless remain organically connected to his earlier methods of composition.