![]()

The Hammerklavier Sonata, Opus 106

Nicknames stick. By now it is too late to call this work anything but the “Hammerklavier Sonata” although the term could just as well have been attached to its immediate predecessor, Opus 101, which had the same words on its autograph and on the title page of its first edition. Beethoven also used the word Hammerklavier—the German term for the Italian pianoforte—on the autograph of the next sonata, Opus 109. And all this arose from Beethoven’s decision in 1817, in a burst of patriotic enthusiasm, to insist that “henceforth all our works on which the title is in German shall, instead of ‘pianoforte,’ carry the name ‘Hammerklavier. ’ ”1

Perversely it is right that this sonata should have its own special name. In its technical demands, its scale, and its breadth of expressive content, it is a turning point in Beethoven’s third maturity and in the history of the piano sonata. It was indicative of Beethoven’s change of direction after 1812 that he did not have a new symphonic project in hand after finishing the Eighth Symphony in 1812 and would not begin full-time work on what became the Ninth before 1821. Accordingly, composing the Hammerklavier in 1817–18 became the virtual equivalent of working on a symphony.

A notice in the Wiener Zeitung in 1819, surely written with Beethoven’s knowledge, claims that “the work is distinguished among all other creations of the master, not only by virtue of its richness and greatness of imagination [phantasie] but because, in its artistic completeness and use of strict style, it signals a new period in Beethoven’s keyboard works.”2 For once journalism was justified.3

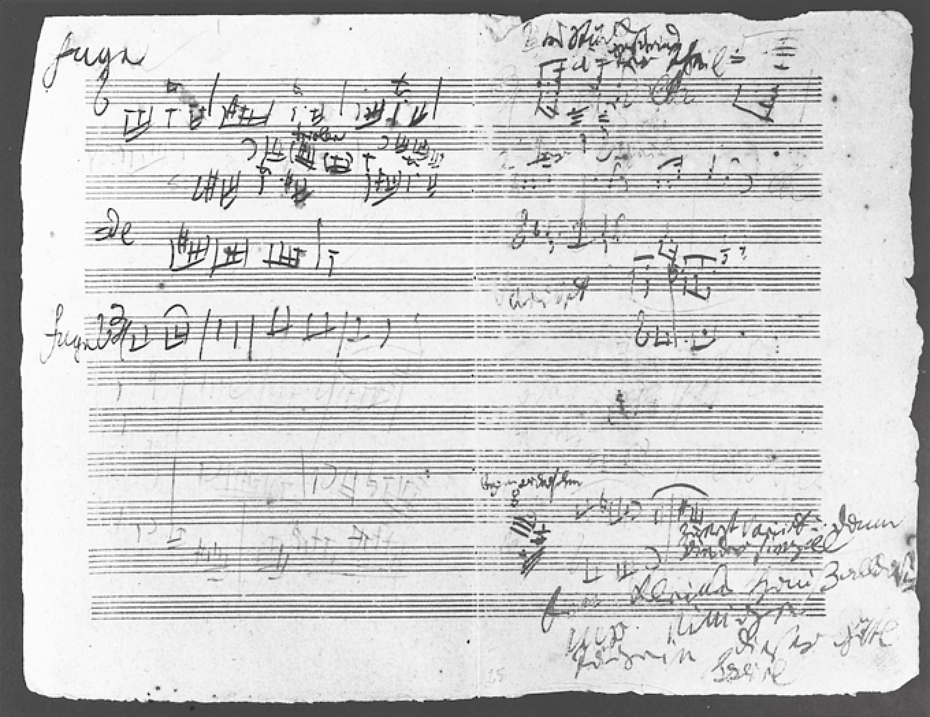

Sketches for Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Opus 106 (Hammerklavier), from a pocket sketchbook of 1818. (Bibliothek der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, Vienna)

Its most obvious features are its length and complexity. It is immense in the way that the Eroica is among the symphonies or Opus 59 No. 1 is among the quartets. These are not just sizable and big-boned works; they are incomparably the longest that anyone had written in their genres. They are monuments to the part of Beethoven’s vision that needed expanded scope for the expression of powerful ideas—intellectual as well as emotional—and long time-spans to provide room for a wealth of thematic ideas and harmonic procedures within a fully organized formal framework. Not that he could not achieve comparable results in shorter spans, as he often did. Rather, in these big four-movement cycles he takes pains to spread his ideas and their consequences across huge canvases. Something similar was surely in Michelangelo’s mind when he decided on the great physical size of his seated Moses for the tomb of Julius II.

We remember that the sheer length of the Eroica had been publicly noted on the first violin part of the first edition—“this symphony having been written at greater length than is usual.” Also, at the last stages of composing Opus 59 No. 1, Beethoven had reined himself in and decided not to make each of the first two movements half again as long as they already were, and not to add a long repeat that he had penciled in for the end of the last movement. Attending to proportion and balance among the segments of large-scale formal structures, whether sonata-form movements or others, was a lifetime preoccupation, and the study of Beethoven’s proportions within movements is one of the many tasks for which his sketchbooks, still only partially transcribed and available, may yield valuable new knowledge.4

When we consider that Beethoven had produced twenty-eight highly varied piano sonatas beginning in the 1790s, the grand aesthetic model that he chooses for the Hammerklavier is a breakthrough. In his early published piano sonatas he had increased the genre’s aesthetic weight by writing full four-movement cycles; soon thereafter, in 1800–1802, he had begun to alternate this template with three-movement sonatas or still other models, as in Opus 27 Nos. 1 and 2, or in Opus 31, where two sonatas have three movements. It is true that the “Waldstein” had greatly increased the gravity of the piano sonata, but it did so by having two quite long movements separated by a short Adagio introduction to the finale. By 1819, in fact, he had not written a four-movement piano sonata since Opus 31 No. 3, composed in 1802. Similar alternatives govern his middle period violin and cello sonatas, as we see from the three-movement “Kreutzer” Sonata and the pseudo-four-movement Cello Sonata Opus 69, in which the decision to abbreviate the beautiful slow movement seems to take place as the sonata unfolds. Thereafter he produced two large, four-movement cycles in his keyboard chamber music, the “Archduke” Trio in 1811 and the G Major Violin Sonata in 1812, each of them his last word in its genre.

Of the two, the “Archduke” Trio, in the same key of B-flat and dedicated to the same patron, comes closest to being a model for the Hammerklavier, the largest of all Beethoven piano sonatas.5 The analogy in length is clear. Less clear is that in their first movements the two works share important features of their harmonic plans, in both cases using chains of descending thirds from the tonic, B-flat major, across the scope of the exposition and development sections. In this sonata, as Charles Rosen has vividly shown, descending thirds play an important role in integrating the whole work; their employment here is a later realization of Beethoven’s earlier uses of descending-third chains, a process he had derived from Mozart and Haydn, and which he may also have found in Bach as well, especially at this Bachian stage of his development, when he would have been looking for it.6 In the “Archduke,” the subdominant is the first harmonic contrast to the tonic, and a descending-third chain governs the big second theme in the cello, thus anticipating the thirds of the Hammerklavier. Further in the “Archduke,” as we saw, the tonal plan of the exposition moves not from the B-flat tonic to its dominant, F, as we would normally expect, but rather to G major.7 From there an abrupt shift is needed at the end of the exposition either to restore the tonic for the repeat of the whole section or to go on into the development. In the development the next goal is indeed E-flat major, in which the cello arrives with an expressive variant of the first theme to seal the moment. The final steps bring a rare touch of the minor mode—C minor—then finally settle back into the orbit of the tonic B-flat major well before the dolce recapitulation.8 This comparative absence of harmonic tensions before the recapitulation differs altogether from the situation in the Hammerklavier, signaling the more relaxed and leisurely character of the “Archduke”’s first movement. But the harmonic planning is essentially the same in the exposition and early parts of the development.

Certainly the two works differ sharply in other ways. The piano trio impresses for its nobility and optimism—like the Pastoral Symphony before the storm, it makes hardly any use of minor mode. As we saw earlier, the first movement of the trio is followed by an enormous Scherzo with fugato Trio, the slow movement is a well-crafted set of variations, and the finale is in a relaxed 2/4 meter animated by rhythmic shifts that come in fits and starts between the stringed instruments and the piano. The Hammerklavier, on the other hand, builds through three enormous movements to its fugal finale, giving the work an end-orientation quite different from that of the “Archduke” Trio.

The Hammerklavier starts with a classic Beethovenian physical opening gesture, an eight-note marcato figure, memorable for its rhythm alone, that rises in thirds as it is repeated and comes to a stop; then the legato main theme emerges and comes to another stop. A sketch for this opening idea has the words “Vivat Rudolphus,” showing that the eventual dedication was anything but perfunctory. The two elements—opening motif and main theme, both demanding continuation—establish a high state of tension, somewhat like the opening of the Fifth Symphony, with its two pauses, or the Fidelio Overture, with its incisive rhythm and repetitions rising through the tonic triad. In the Hammerklavier opening this tension increases as the movement progresses, partly owing to the large number of rhythmically profiled thematic ideas and to the long fugal episode that marks the development section. It also arises from the movement’s further harmonic advances into distant regions (G-flat major, B minor) as well as to its stark contrasts of dynamics. Forte accents on weak beats appear like explosions at the end of the first movement, and nothing could be more characteristic of this sonata than the dynamics in the last seven measures, in which a diminuendo moves down from an already established piano to piano sempre and then to the very rare pianississimo; then the registrally extreme fortissimo tonic chord breaks out suddenly, just preceding the final unison ![]() .

.

This sonata was written just after Beethoven had received Broadwood’s handsome gift of a six-octave grand piano from London, in 1817. If the Broadwood tone was perhaps less brilliant than that of Viennese pianos, its capacities for a wide range of dynamics and tonal shading compensated well. And modern performances of Beethoven’s later sonatas on a restored Broadwood should convince anyone that tonal shading, subtlety of dynamics, and beauty of sonority, were now more vital than ever in Beethoven’s conception of keyboard writing.9

The spaciousness of the Hammerklavier is further apparent in its Scherzo and Trio, and even more in the heavily freighted F-sharp-minor Adagio sostenuto, one of Beethoven’s longest brooding slow movements, of which Adorno curiously remarked that its opening melody “lacks plasticity,” shows “the disappearance of surface articulations,” and is “stretched over long arches.”10 Had this been a second-period work, even a late one like the “Archduke” Trio, its finale might have been light, to balance the whole work, rather than even more monumental. But Beethoven made the latter choice and added greater weight at the end. After an improvisational Largo and Allegro introduction in the manner of a fantasia, itself a succession of strange and seemingly unrelated figures that mysteriously point the way to a new aesthetic state, that new state indeed emerges as a vast fugue for three voices, “con alcune licenze” (“with some deviations from strict writing”). It is the biggest and most complicated fugue that Beethoven had yet written.

This fugue was conceived on a grand scale, compared with the fugal finale of the D Major Cello Sonata Opus 102 No. 2 written a couple of years earlier, which is an amply dissonant fugato movement, not a strict fugue, with three large segments welded together into a whole. The Hammerklavier fugue subject is unusually long. After some intervallic anticipations it begins with a great leap of a tenth, which clearly recalls the emphatic leap that opened the first movement, while a trill intensifies the leading-tone-to-tonic motion in a startling way (*W 45). (Beethoven would later use a similar figure in his other late B-flat-major fugue, the Grand Fugue, Opus 133—in many ways the great descendant of this one—where insistent trills on isolated note pairs play a powerful role.) In the fugue of Opus 106, after the opening upward gesture, the descending-third chain of the ensuing figures closes into a series of running sixteenth patterns that form a larger melodic shape through which the descending thirds in fact continue to be heard.

The fugue unfolds in two ways. One is in its contrapuntal transformations of its subject in a time-honored manner. We find passages devoted to the subject in augmentation, the subject in retrograde with a new countersubject, and the subject in inversion.11 Far from supposing that Beethoven is “merely displaying erudition” or “submitting” to so-called constructivist principles of fugue writing in using augmentation, retrograde, and inversion to manipulate thematic material, we see that their characteristic functions as developmental features of fugue are essential to the aesthetic he is embracing in this finale. His aim in this movement is to rival Bach’s capacity to expand and rejoice in displays of rigorous formal logic and contrapuntal skill while infusing them with that “poetic” element (as Beethoven himself called it) that is fully his own.

After the first section, we encounter a new and contrasting second subject, made of steadily flowing quarter notes in 3/4 meter, as even and regular as the first subject had been abrupt and barely predictable. The new subject receives a full exposition,12 and once this thematic antithesis is established, even the least sophisticated Hegelian can predict the outcome: the two themes will eventually be combined and then give rise to new and more intensified contrapuntal combinations that will form the peroration of the movement. It is exactly the principle that Beethoven later used in the finale of the Ninth Symphony, where the “Ode to Joy,” the theme of brotherhood, and the great second theme, speaking to the millions under God, combine in a climactic double fugue. In the Hammerklavier, the combinational features include not only the two themes in a consonant contrapuntal relationship to one another, but the renewed appearance of Theme 1 in both its original form and its inversion. All this, and the sonata as a whole, is then crowned by a lengthy coda that caps all previous climaxes: low roaring trills in the bass register, a short Poco adagio to set up the dynamic finish, rushing unison scales on the original Theme 1, and trilled fortissimo octave pairs, all of this working out to the last possible degree the implications of the upward leap that started the fugue off in the first place—and had also started off the whole sonata. As in many a mature work, Beethoven seeks to draw the last ounce of meaning from even the simplest figures and develops the material of a vast movement through to an ending that feels and sounds as absolute as it is inevitable.

As indicated earlier, a remarkable feature of this sonata is that Beethoven, in sending it to Ries in 1819 for publication in London, authorized him to publish it in one of three ways: (1) “you could . . . omit the Largo and begin straight away with the Fugue”; (2) “you could use the first movement and then the Adagio, and then for the third movement the Scherzo”; or (3) “you could take just the first movement and the Scherzo and let them form the whole sonata.”13 What are we to make of this? Has Beethoven “momentarily lost confidence in the value of his effort[?]”14 Perhaps, though it seems unlikely. We are aware of the perpetual economic factor in Beethoven’s shrewd and calculating ways with publishers. To gain a quick British edition of so difficult a work was so important that he would accept virtually any partial or variant published version. Not only did he urgently need money to finance Karl’s education, but his principal supporter, the archduke, was in some financial straits at this time. As Beethoven tells Ries in this same letter, “my income has vanished.” He also makes clear that he wants the fee for any British version as soon as possible so that he can release the work to the Viennese publisher, “who has really been kept waiting too long.” As usual he could expect only a one-time payment, and he urgently wanted to get one from each publisher before piracy set in.

In any event, the sonata came out in Britain in a two-part version: the first part contained the first three movements (with the second and third in reversed order!) and the second part consisted of the Introduction and Fugue. This concession for an unusually long and difficult work could have been in his mind seven years later, when he was urged to detach the even longer, even more arcane, fugal finale from his B Flat Quartet, Opus 130, and he agreed, creating the Grand Fugue, Opus 133, as a separate work.

With the publication of Opus 106, seemingly unfathomable and to most musicians unplayable, the piano sonata could never be the same again. It is against the background of this monumental achievement that we must see the last three piano sonatas. Resolutely original, independent, fully realized masterpieces that they are, we can nevertheless dimly perceive that they form a trilogy, the more so as they originated as a group from a commission by Adolph Martin Schlesinger in Berlin in a letter to Beethoven of April 11, 1820. Although Schlesinger’s letter is lost we know what it must have said, since Beethoven told him on April 30 that, in addition to their discussions about other, lesser works, for forty ducats each he could supply “an opus of three sonatas.”15 As usual he was rushing ahead of himself, for he had only just begun to jot down some ideas for what turned out to be the first movement of Opus 109 while the others were at best dimly imagined visions waiting to be fleshed out. Beethoven was then in the midst of work on the Missa solemnis, and when the deadline for its presentation passed on March 9, 1820, with Archduke Rudolph’s inauguration as archbishop of Olmütz, it was clear that he would need much more time for the completion of the Mass but also that he could turn his attention to some smaller-scale projects—like the three piano sonatas. The first to be finished was the E Major Sonata, Opus 109, which became his main project during the summer of 1820 and was ready by the fall. He then began the next sonata, Opus 110, in the spring of 1821, finishing it by December. Then came his first work on the C Minor Sonata, Opus 111, which he finished much more quickly than the previous two, and he was able to send both Opus 110 and Opus 111 to Schlesinger around February 1822. Still, there was work to do, as Beethoven then revised the second movement of Opus 111 and dispatched the revision in early April 1822. Besides his continuing preoccupation with the Mass, the magnum opus of these years, he managed to finish a set of Eleven Bagatelles for Piano, Opus 119, early in 1821 and also, in the fall of 1822, his overture for the reopening of the Josephstadt Theater, The Consecration of the House.

Beethoven’s pianistic imagination is stamped on every page of these three sonatas. Deaf as he was, his sustained ability to compose at the keyboard—to use his fingers to unleash his imagination—must have released a wealth of new ideas. Undreamed-of sonorities and multivariate figuration patterns appear in each of these works, exploiting both keyboard and pedals in ways that went beyond even his most innovative earlier keyboard works. We find arpeggiated cadenzalike passages through several octaves; rapid parallel thirds and sixths; delicate figurations; use of una corda pedal effects; and sustained trills in extreme registers against continuing melodic and contrapuntal lines in other parts. In each case these pianistic effects were grounded in the structural marrow of the individual movement and of the work as a whole. Moreover, each sonata has an idiosyncratic design in which the form arises even more dramatically from the material than it had in even the most original middle-period works. Here the macroscopic formal shaping is even more fully detached from the expected norms because Beethoven had moved away from the processive developmental methods that tended to govern his major works before 1815 (except those experimental, fantasialike works such as the “Moonlight” and “Tempest” Sonatas). In the late sonatas we feel that the form is in process of emerging as the material of a given movement realizes its potential from beginning to end. Though such a feeling can always be inferred from true masterworks, here it is more palpable than almost anywhere else in Beethoven. The psychological aspect of what I call the “process of emergence” is given primacy, and the traditional means by which formal expectations were created and satisfied in classical sonatas, even in his most path-breaking earlier ones, are often suspended, elided, or concealed. This concealment of formal junctures is a basic aspect of the late style, and it is in its glory in these three works.

Sonata Opus 109

If we consider the three sonatas as totalities we see that Opus 109 is somewhat ambiguous in the weight and balance of its movements. It has a curious three-movement plan: Vivace, a short and intense rapid-tempo first movement in the tonic, E major; Prestissimo, a still more rapid Scherzo in the tonic minor; and Andante molto cantabile ed espressivo in E major (theme and six variations plus coda), a calm, deeply expressive movement, the longest of the three, to conclude. The sequence of tempos is unprecedented: Beethoven had previously used a first-movement Vivace only in the Seventh Symphony, reserving it mainly for finales, as in the Fourth Piano Concerto and the Lebewohl Sonata. Even for this purpose he had only begun to use Vivace to replace Allegro or Presto as a finale tempo in a few middle-period works; it was becoming more frequent in his last works, above all in the Scherzos of the last quartets. As for Prestissimo as a faster variant for Presto, he had used it as a main tempo in three early piano works but not since.16 And as for ending with a variation set, this in itself is not a radical step, but the intensity of this movement and its many tempo changes breaks with its precedents (such as the finale of the “Harp” Quartet, Opus 74). The theme itself, which Beethoven labeled in German “Gesangvoll, mit innigster Empfindung” (“Songlike, with the greatest inwardness of feeling”), is a magnificent specimen of “hymnlike” melodies in Beethoven slow movements. Each variation then carries its own tempo or character designation and in some cases a new meter: (1) Molto espressivo; (2) Leggiermente; (3) Allegro vivace, 2/4; (4) “Etwas langsamer als das Thema” (“A little slower than the theme”), 6/8; (5) Allegro, ma non troppo, 4/4; and (6) “Tempo I del thema” (“Original tempo of the theme”) for the final peroration. There is evidence in Beethoven’s autograph that the first movement goes right on to the second without pause, despite his having written “attacca” and then canceled it. And Nicholas Marston has shown that the same immediacy of connection is wanted between the Prestissimo and the variations finale.17

Even more surprising is Marston’s discovery that the order of composition of the movements, as disclosed in the sketches, is quite unusual. To begin with, the first movement was apparently planned as a separate composition, intended for a piano method by Friedrich Starke, and Beethoven’s friend Franz Oliva spurred him to use the “little new piece” as the first movement of the new sonata he needed for Schlesinger.18 It seems clear that, once he decided on the change, Beethoven went ahead and composed, first, the third-movement theme; then the second movement; then the third-movement variations. Afterward he undoubtedly revised the whole to bring it all into its fully mastered coherence, in which, as Marston remarks, the third-movement theme “effectively recomposes the first movement and concludes its [structural] ‘unfinished business’ while also foreshadowing the structure of the third movement.”19

Sonata Opus 110

The compactness and brevity of the first movement of Opus 109 is mirrored in that of Opus 110 (a fairly short Moderato cantabile movement), but the continuation of this second sonata brings an entirely different pattern. The F-minor Scherzo is a fierce counterpart to the Prestissimo of Opus 109, but then the sonata turns in a wholly new direction. A short Adagio introductory phrase gives way to a dramatic and atmospheric Recitativo that closes into a “Klagender Gesang” (“Song of Lament”) in ![]() minor. This “arioso,” of transcendent beauty and depth, turns out to be a lyrical preparation for the main body of the finale, which emerges as a fully developed fugue in the home tonic of A-flat major on a subject that clearly derives from the opening theme of the first movement.

minor. This “arioso,” of transcendent beauty and depth, turns out to be a lyrical preparation for the main body of the finale, which emerges as a fully developed fugue in the home tonic of A-flat major on a subject that clearly derives from the opening theme of the first movement.

This poetic fugue is another example of Beethoven’s late-period blending of cunning contrapuntal artifice with his most expressive modes of utterance. It finds room halfway through for a return of the “Klagender Gesang” in G minor, a key remote from the home tonic, even in Beethoven’s uses of extended tonality. The fugue subject then returns in inverted form in G major. After further modulatory and contrapuntal adventures, including augmentation and diminution, the subject finds its way back to A-flat major and launches into a coda that synthesizes all earlier complexities, while it also confirms the sense of homecoming by bringing the subject triumphantly in high register and in full chordal style while the left hand rolls sixteenth-patterns below. Finally the whole suggests a circular time-space by its closing reference back to the cascading tonic arpeggios of the first movement.

Sonata Opus 111

The last sonata gives every sign of being a self-consciously final statement. There is no evidence that after Opus 111, Beethoven ever thought of writing another piano sonata, as he moved on to complete his other grand projects. Nothing in the general literature is more familiar than speculation as to why this C-minor sonata has “only” two movements, and no controversy is more useless. In July 1822 Maurice Schlesinger, by now established in Paris, wrote to Beethoven to thank him for entrusting “your masterworks” to him and his father for publication, but also asked “most submissively, if you wrote for the work only one Maestoso and one Andante; or if perhaps the [final] Allegro was accidentally forgotten by the copyist.”20 Ten days later his father wrote from Berlin with the same question.21 If Beethoven bothered to reply we don’t know; the chances are that he simply passed it over in grim silence. Schindler also claimed to have been worried about the absence of a third movement, and writes that he asked Beethoven for an explanation. This time Beethoven replied that he hadn’t had time to write one, an answer whose irony was probably lost on Schindler.22 The lack of any sketches or even jottings for a potential third movement makes it apparent that Beethoven never intended the Arietta to be anything other than the final movement.23 Even so, the question continued to be asked, as when Wendell Kretzschmar, Thomas Mann’s Pennsylvania-born music teacher in Doctor Faustus, found himself lecturing to a bored general audience on just this issue, stuttering violently as he tried to convey to his lay audience what premonitions of greatness and death lay in this movement, which could not possibly be followed by anything else.24

The opening of the Maestoso, with its forte jagged downward leap of a diminished seventh followed by a full diminished seventh chord on F![]() , creates an immediate instability, a harmonic crisis that defines no tonic, until it finds its way in a softer dynamic to an apparent clarifying cadence in C minor (*W 46). But then in succession we encounter the other two diminished sevenths of the tonal system, those on

, creates an immediate instability, a harmonic crisis that defines no tonic, until it finds its way in a softer dynamic to an apparent clarifying cadence in C minor (*W 46). But then in succession we encounter the other two diminished sevenths of the tonal system, those on ![]() and on

and on ![]() , expanding the last of these through winding ways until, finally, the dominant of C minor breaks the suspense, preparing the way to the Allegro first movement. The diminished-seventh leaps of this extraordinary opening have a strong impact on the later course of the first movement.25 So striking and pre-Romantic, this opening has a precedent in another genre: it is, again, the introduction to Florestan’s dungeon scene that opens Act 2 of Fidelio, which uses all three diminished-seventh chords of the tonal system and a two-note, heartbeat figure in the tympani tuned to a diminished fifth.26 The larger shape of the sonata grows organically from this opening Maestoso. The C-minor Allegro movement not only has strong affinities with other representatives of Beethoven’s “C-minor mood” but its opening theme was consciously associated by Beethoven with two great precedents—one is the fugue subject of the Kyrie in the Mozart Requiem, the other is the subject of the fugal finale of Haydn’s F Minor String Quartet, Opus 20 No. 5; Beethoven wrote both of these out on a sketch leaf that contains a draft of the beginning of the Maestoso.27 There are indications that at a preliminary stage of composition Beethoven considered writing the first movement of the sonata as a fugue, based on a subject he had originally sketched as early as 1801 while working on the Opus 30 violin sonatas.28 He even wrote out a full fugal exposition, which was suppressed in favor of the sonata-form movement as we have it. What these drafts show is the decisive importance of contrapuntal thinking in his last piano sonatas and in his last maturity altogether.29 It also appears that the Maestoso introduction only emerged in the plan of the work when Beethoven had given up the idea of a fugal first movement and reshaped it into sonata form, thus providing an introduction that would be integral to the whole work. “[H]e considered using it at the end of the development section, to prepare the recapitulation of the main theme, [and] he contemplated bringing it back towards the end of the second movement.”30 We see here the malleability of Beethoven’s formal thinking in mapping out the larger plans of his late works, something we also find in the late quartets, in which at least two movements were transferred from one work to another.

, expanding the last of these through winding ways until, finally, the dominant of C minor breaks the suspense, preparing the way to the Allegro first movement. The diminished-seventh leaps of this extraordinary opening have a strong impact on the later course of the first movement.25 So striking and pre-Romantic, this opening has a precedent in another genre: it is, again, the introduction to Florestan’s dungeon scene that opens Act 2 of Fidelio, which uses all three diminished-seventh chords of the tonal system and a two-note, heartbeat figure in the tympani tuned to a diminished fifth.26 The larger shape of the sonata grows organically from this opening Maestoso. The C-minor Allegro movement not only has strong affinities with other representatives of Beethoven’s “C-minor mood” but its opening theme was consciously associated by Beethoven with two great precedents—one is the fugue subject of the Kyrie in the Mozart Requiem, the other is the subject of the fugal finale of Haydn’s F Minor String Quartet, Opus 20 No. 5; Beethoven wrote both of these out on a sketch leaf that contains a draft of the beginning of the Maestoso.27 There are indications that at a preliminary stage of composition Beethoven considered writing the first movement of the sonata as a fugue, based on a subject he had originally sketched as early as 1801 while working on the Opus 30 violin sonatas.28 He even wrote out a full fugal exposition, which was suppressed in favor of the sonata-form movement as we have it. What these drafts show is the decisive importance of contrapuntal thinking in his last piano sonatas and in his last maturity altogether.29 It also appears that the Maestoso introduction only emerged in the plan of the work when Beethoven had given up the idea of a fugal first movement and reshaped it into sonata form, thus providing an introduction that would be integral to the whole work. “[H]e considered using it at the end of the development section, to prepare the recapitulation of the main theme, [and] he contemplated bringing it back towards the end of the second movement.”30 We see here the malleability of Beethoven’s formal thinking in mapping out the larger plans of his late works, something we also find in the late quartets, in which at least two movements were transferred from one work to another.

The Arietta with its variations is in every sense a slow finale, not a slow movement that lacks a further movement as confirmation. Labeled “Adagio molto semplice e cantabile” (“Adagio, to be played very simply and in a singing manner”), it presents a theme of absolute directness and clarity. It is followed by four intricate variations that, as always, closely follow the contour and harmonic pattern of the theme, then a modulatory episode that breaks out of the C-major framework for an excursion to E-flat major and C minor, then a vast reprise of the theme with new figuration patterns streaming forth in the lower voices, and at the end a soaring conclusion with high trills in the upper register over a final statement of the first part of the theme, plus a poignant chromatic inflection (*W 47).31 Mann’s fictional music teacher, Wendell Kretzschmar, is speaking of this moment when he says that it represents

something entirely unexpected and touching in its mildness and goodness . . . [T]his added ![]() is the most moving, consolatory, pathetically reconciling thing in the world. It is like having one’s hair or cheek stroked, lovingly, understandingly, like a deep and silent farewell look. It blesses the object, the frightfully harried formulation, with overpowering humanity, lies in parting so gently on the hearer’s heart in eternal farewell that the eyes run over.32

is the most moving, consolatory, pathetically reconciling thing in the world. It is like having one’s hair or cheek stroked, lovingly, understandingly, like a deep and silent farewell look. It blesses the object, the frightfully harried formulation, with overpowering humanity, lies in parting so gently on the hearer’s heart in eternal farewell that the eyes run over.32

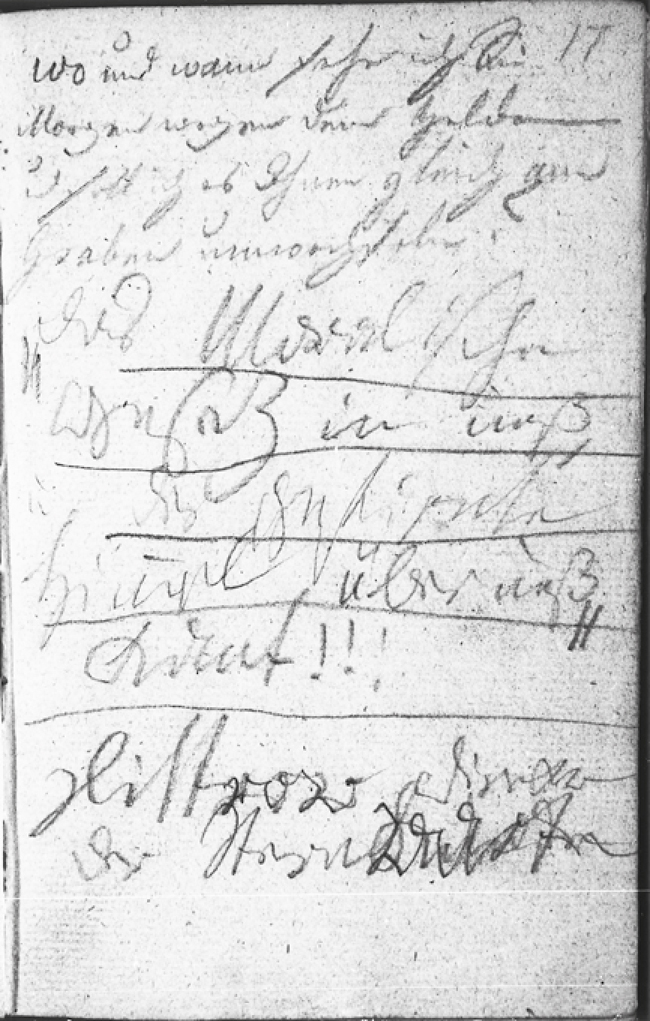

The Arietta’s ending, in which the basic melody, now wreathed in accompanying figures, soars to higher regions, raises the conclusion of this work to the level reached at the end of Opus 109 by the quiet return of its Andante theme, and to the end of Opus 110 by its arpeggiated harmonies flying downward and then upward in a vast registral arch. In each instance we have the feeling that an incomparable musical experience has come to its end, has reached a wisdom that is granted only to the greatest artists. In early February 1820, Beethoven wrote the Conversation Book entry quoting Kant: “The moral law within us, and the starry heavens above us. Kant!!!”33 It is just this spirit, of the mortal, vulnerable human being striving against the odds to hold his moral being steady in order to gather strength as an artist to strive toward the heavens—it is this conjoining that we feel at the end of Opus 111 and in a few other moments in Beethoven’s last works. They are moments that few composers before or after him ever quite achieved.

The strength of purpose behind Beethoven’s large-scale late works makes it biographically useful to know that some of them came about through special circumstances, such as the archduke’s elevation to a high church position and the reopening of the Josephstadt theater; or through commissions from patrons such as the Philharmonic Society of London and Prince Galitzin. Some came from publishers, including Schlesinger, Schott, and Diabelli. Of these only Diabelli stumbled into immortality by having his name affixed to Beethoven’s last, and by far greatest, set of variations for piano, to which Beethoven once referred as “grand variations on a German waltz,” begun in 1819 and not completed until 1823. In 1817 Anton Diabelli, a journeyman composer and sometime proofreader for Steiner’s publishing house, set up shop, with Pietro Cappi as his partner, in a new music-publishing venture located in the Kohlmarkt, a square in Vienna. By early 1819 he was doing a brisk business in arrangements of operatic and dance tunes for piano and for guitar. A little later he established a connection with a promising younger Viennese composer, Franz Schubert, and in 1821 published his lieder “Erlkönig” as Schubert’s Opus 1 and “Gretchen am Spinnrade” as Opus 2. Early in 1819 Diabelli conceived the sure-fire idea of combining popular appeal with patriotism, though less flamboyantly than Mälzel had done with his Panharmonicon and Wellington’s Sieg. Diabelli, who had a background as a piano teacher and composer, wrote a thirty-two-bar waltz tune in C major and sent it off to every important or would-be important composer in Austria, asking each of them to contribute a variation on the tune for a collection to be entitled “Vaterländischer Künstlerverein” (“Patriotic Association of Artists”). Not all replied, and Beethoven went his separate way, but by 1824 fifty composers had sent in one variation each, and Diabelli proudly published them in 1824 with a handsome title page. The roster, ranging alphabetically from Assmayer to Worzischek, included Czerny, Gelinek, Hummel, Friedrich August Kanne, Conradin Kreutzer, Ignaz Moscheles, W. A. Mozart the younger, Schubert, Tomaschek, and the child prodigy Franz Liszt. One variation is ascribed to “S.R.D.” (“Serenissimus Rudolphus Dux”) on the title page; in fact the archduke contributed a very professional fugal variation.34 Czerny was not only the first to come on board (his variation is dated May 7, 1819, on the autograph), he also rounded out the collection with a coda.35

A page from a Conversation Book of 1820 showing Beethoven’s inscription, “The moral law within us and the starry heavens above us. Kant!!!” (Staatsbibliothek, Berlin)

Obviously struck by Diabelli’s waltz, a simple springboard for his imagination, Beethoven decided in the spring of 1819 to work up a full-scale set of variations, and we now know that he sketched as many as nineteen of the eventual thirty-three variations before he put the project aside. He had to in order to continue his work on the Missa solemnis and then the last three piano sonatas, and he did not return to the variation cycle until 1823.36 In other words, when Beethoven began the “Diabelli” Variations he had just finished the Hammerklavier Sonata and had begun work on the Mass; by the time he finished it the Mass was complete, as were the last piano sonatas, and he was moving into work on the Ninth Symphony and contemplating a quartet in E-flat major that would become Opus 127.

Why thirty-three? Many reasons have been advanced, mainly drawn from analytical studies of the growing complexity of structure and expression in the course of the work, but it should also be noted that in the year before the “Diabelli” Variations Archduke Rudolph, as part of his training, had composed a set of forty variations on a theme by Beethoven. It is possible that Beethoven’s own plan for a large variation set could be related to a letter of 1819, in which Beethoven tells Rudolph that he is at work on the great Mass for the archduke’s installation, but also that “in my writing-desk there are several compositions that bear witness to my remembering Your Imperial Highness and I hope to work on them under more favorable conditions.”37 This suggests that in writing his longest variation set, one variation longer than Bach’s “Goldberg” Variations (counting Bach’s two presentations of the theme plus thirty variations) and his own Thirty-two Variations of 1806, Beethoven could also have had it in mind to create a panoramic set of elaborations upon a simple tune, demonstrating a wide range of approaches to variation in his ripest manner and showing his contemporaries and future audiences what immense possibilities lay within Diabelli’s sequential “cobbler’s patch.” The whole would show how a monumental musical experience could be carved out from this seemingly trivial little dance number. It is highly probable that Beethoven knew the “Goldberg” Variations, as they had been published in 1817 in Zurich, and a manuscript copy could have reached him even before that.38

Diabelli’s waltz is actually a well-crafted, symmetrical little piece, not just a simple tune (*W 48). From this slender stalk Beethoven builds a variation set that grows aesthetically in stature from beginning to end, putting the most traditional of genres on a completely new footing. As much as he had made innovations in some of his earlier independent sets of piano variations—the Six Variations of Opus 34 and the Fifteen Variations and Fugue of Opus 35—here he goes beyond precedents, his own or anyone else’s. There are changes of tempo and character not just for some variations but for almost every one. The range extends across the Alla Marcia of No. 1, the swirling, pre-Romantic waltz of No. 8, the Grave e maestoso of No. 14, and the Presto scherzando of No. 15. Number 20 brings a strange and dissonant chorale, to which No. 22 opposes a naked parody of Leporello’s “Notte e giorno faticar” from the opening of Don Giovanni, chosen for its obvious affinity to the opening intervals of Diabelli’s tune. The final three variations expand in feeling and depth, reaching out in new directions. No. 31 is a Bachian arioso that is followed by a rigorous fugue (thus paralleling the Arioso and fugue of the Opus 110 finale). The whole is crowned by simplicity: the final word in No. 33 is reserved for a freely developed “Tempo di Menuetto,” a graceful and gentle conclusion that steps back historically from the waltz era to that of the minuet, then builds up at the end to a sublime ending in C major with familiar late-Beethoven keyboard figurations interwoven with fragments from Diabelli’s tune. The path to the transcendental has once again been traversed, now all the way from the Viennese ballroom through human tragedy and comedy, finally arriving once more, and by a different route, at the starry heavens.

Opus 33

The term “bagatelle” from the French means “trifle” but also refers to a game something like billiards, played with four to nine balls on a flat table with cups at the corners. The word was rare in music before Beethoven. It first appeared in a few French titles in the eighteenth century, for example, a 1717 rondeau by Couperin and a set of dances issued by the publisher Boivin around 1753. Later, and more relevantly for Beethoven, a certain Carl Wilhelm Maizier issued a set of Musikalische Bagatellen in 1797 that combine dance pieces with songs. But Beethoven was the first to use the term for detached, short piano pieces, at first for his collection of seven Bagatelles pour le Pianoforte (using the French form of the term), Opus 33, published in 1803 by the Viennese Bureau d’Arts et d’Industrie. In it he brings together a selection of the many short piano pieces he had been writing since the Bonn years, and one of the seven (No. 1, a simple rondo in E-flat major) actually bears the date 1782 (originally written 1788). Beethoven put these dates on his autograph manuscript in 1802 when he was assembling this set, no doubt trying to remember just when he had originally written the piece. The main point about Opus 33 is that it was an assemblage of disparate little pieces that Beethoven brought together, not a set that he planned as a collection having any special unity. He always had a raft of little piano pieces somewhere at hand, some of them rejects from piano sonatas, some just advanced exercises. The “Kafka” miscellany contains many of them.

Opus 33 displays a small wealth of pianistic figurations used as bases for little pieces, but only two numbers have real expressive merit: No. 6, a D-major Allegretto quasi Andante, which Beethoven marks “Con una certa espressione parlante” (“With a certain speaking quality of expression”), is the only one of the set that has a pensive, touching quality; the other is No. 7, a Presto quasi-scherzo piece in A-flat major in Beethoven’s most brilliant and rhythmically exciting manner, some of it a counterpart to the angular Scherzo of the “Pastorale” Piano Sonata, Opus 28, and in its quiet, arpeggiated octaves a parallel to the Scherzo of Opus 10 No. 2 and the first Allegro of the Sonata Opus 27 No. 1.

Opus 119

Beethoven came back to the idea of the bagatelle in 1820 to 1822, the period of his main work on Opp. 110 and 111, just after the Missa solemnis and probably just before his return to the “Diabelli” Variations in 1823. The result was the collection of eleven Bagatelles, Opus 119, issued in 1823 by Maurice Schlesinger in Paris, curiously bearing the Opus number 112 (it took until the middle of the nineteenth century before the final opus number 119 was established).39 Beethoven had actually published five of the pieces, Nos. 7–11, in 1821 in a piano pedagogy book by Friedrich Starke, with a note using the German word Kleinigkeiten (“trifles”) rather than the French bagatelles, no doubt in keeping with his patriotic preference for German terms and titles in these years (e.g., Hammerklavier). The note in Starke’s publication told the performer to see in these pieces that “the unique genius of the famous master shines through in every piece, and that these pieces, modestly labeled ‘Trifles’ by Beethoven, will be as instructive for the player as they will provide the most perfect insight into the spirit of composition.”40 Actually Beethoven culled the first five from a portfolio of such pieces he had been keeping over the years, marked “Bagatellen,” of which the cover still survives in Bonn.41 He looked at pieces he had first sketched as long before as 1791–1802, then selected what he wanted for his new collection as Nos. 1–6, adding Nos. 7–11 from the Starke collection already published.

Some aspects of the Opus 119 Bagatelles show Beethoven thinking about how to order them effectively and establish a modest degree of unity in the set, but what appeals most about the collection is found not in the set as a whole but in the single pieces. Like decorative ornaments to the great jewels of Opp. 110 and 111, these bagatelles show Beethoven’s ability to convey a sense of completeness within the smallest boundaries. The longest piece in the set totals seventy-four measures (No. 1 in G minor), the shortest, No. 10 (marked “Allegramente”) in D major, is a mere thirteen, and six more pieces are less than thirty measures long. That he would take pains with them when he was working out the Missa solemnis, the “Diabelli” Variations, and the Ninth Symphony shows that these are serious little compositions, representing his miniaturist side as explorer of aesthetic extremes. The same tendency crops up here and there in the late quartets: witness the tightly compressed Scherzo of Opus 130.

Opus 126

When we come to Opus 126 we see Beethoven deepening the expressive qualities of his short piano pieces once more, and now thinking of them as a cycle, not merely an assemblage. These six Bagatelles were not dredged up from earlier times but were written in February and March of 1824, directly after his completion of the Ninth Symphony. Once again composing elegantly for the piano was a welcome break from his fierce concentration on the Ninth, just as in 1814 he had turned to the songlike Opus 90 directly after the revision of Fidelio. These pieces were planned as a unit; they appear in a group on successive leaves of a sketchbook and are labeled “Ciclus von Kleinigkeiten” (“cycle of trifles”). The term “cycle” indicates that they are intended to be movements of a single work, but it may also refer to the major-third cycle that connects their keys.42 Performing them as an integral whole has become an appropriate modern practice, and thus their convincing sequence of expressive and psychological moods comes forth with something of the same artistic conviction we find in a larger complex work—the closest we come to this set is, indeed, the short middle movements of the quartet Opus 130, not only with its diminutive Scherzo but its other little movements that culminate in the aria-like cavatina, just prior to the finale.

In Opus 126 we find the following key scheme:

| No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Key | G major | G minor | E-flat major | B minor | G minor | E-flat major |

The descending cycle of major thirds is obvious. What seems not to have been noticed is that this type of falling-third sequence, with major thirds descending in order, also governs the main key scheme of the development section of the Eroica first movement, whose key-scheme is C major–A-flat major–E minor–C major. That this same sequence remained in memory is shown by its use in another E-flat-major work, the Quartet Opus 127, which Beethoven was planning just at the time he was writing the Bagatelles of Opus 126. In the coda of the finale, a surprising “Allegro con moto,”43 he turns from the tonic E-flat major that had already been established, to the following scheme: E-flat major–C major–A-flat major–E major–![]() major. This sequence convincingly unfolds in modulatory moves that occupy just a few measures each—another mark of the compactness that is part of Beethoven’s late style.44

major. This sequence convincingly unfolds in modulatory moves that occupy just a few measures each—another mark of the compactness that is part of Beethoven’s late style.44

Such weighty predecessors help justify placing Opus 126 in the main line of Beethoven’s late achievements. These bagatelles are individually longer than most of those in Opus 119, and they are stronger espressively as well: thus No. 3, an Andante cantabile in E-flat major, ranks with the Adagio of Opus 127 and the Lento of Opus 135 in its slowly flowing thematic quality.

Of the late bagatelles it has become a commonplace to say that they anticipate the later Romantic interest in the single song or piano piece, as in Schumann and Chopin, the “fragment,” about which Charles Rosen has written with great insight. Rosen notes, however, that Opus 126 is a genuine cycle, and that when compared with Beethoven’s earlier bagatelles, its pieces have such weight that they “are no longer miniatures.45 What the bagatelles offered Beethoven was a museum of small forms. Also, writing them offered him a chance to look back imaginatively at his compositional methods from much earlier periods of his life, to put himself back even into his earlier child’s world of playing and writing easy piano pieces in his apprentice years. Having long since left that world behind, he could now heighten the features of these playthings that would ensure their place in his later world.