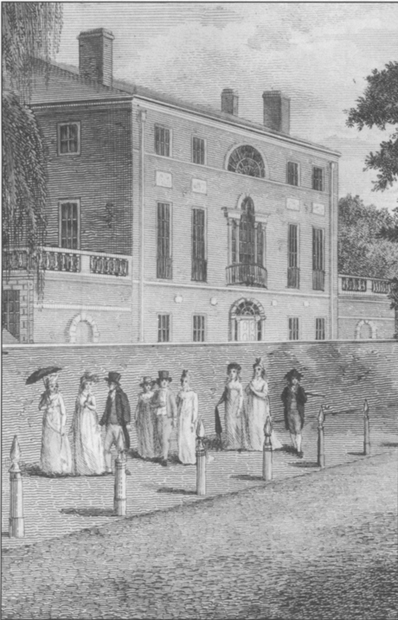

Promenading on Third-street, in Philadelphia, 1798.3

Political passions fade with time, leaving their pale shadows to be recovered by historians who usually affect an objective, if not an amused, detachment from them. American politics have seldom generated the fierceness of passion that they did in their first decade. The extravagant exchanges in the contests between Federalists and Republicans in the late 1790s seem today so to exceed the issues as to merit the patronizing dismissal that scholars have generally given them. After all, the nation survived, President John Adams did not secure the crown to which he allegedly aspired, and President Thomas Jefferson succeeded him without bloodshed. Accordingly the dire predictions of tyranny by journalists like Benjamin Franklin Bache and William Duane in their notorious newspaper, the Aurora, have become mere curiosities, extreme examples of the bad manners that political contests so often provoke.

Not so fast, Richard Rosenfeld warns us. He has studied the newspapers and politics of the 1790s afresh and found the issues to justify all the passion they generated. Scorning the usual detachment, he has embraced as his own the outrage of the men who saw the republic threatened by the thrust for power of those entrusted with running it. He stands up for Benjamin Bache, the beloved grandson of Benjamin Franklin, and he literally and literarily becomes William Duane, Bache’s successor as publisher of the Aurora. He invites us to join him in living through the events that so alarmed these men and to share their alarm in their own words. If we see what was happening as these men saw it, we may emerge with a less complacent view of what it was that the country survived in the 1790s, with a different perspective of what the founding fathers accomplished, even with a new view of who the true founding fathers were.

This is not a typical history, nor does it pretend to be. It is an indictment of some of our customary heroes and a salute to some of our customary villains. It is a piece of historical heresy, written by heretics of the time with the assistance of a kindred spirit who now appeals the sentence of irrelevance that orthodox history has imposed on them. If eternal vigilance is the price of liberty, its vigilant defenders of an earlier time may still have a message for the republic they cherished. That message resounds through these pages.

EDMUND S. MORGAN