Anorexic behavior exists on a continuum between the two extremes of absolute abstinence and bulimia. (For more information on BN and binge-eating disorder, see Peter Cooper’s book in this series, Bulimia Nervosa and Binge Eating.) The eating patterns of the person with abstinent AN involve severely restricting food intake, and closely monitoring and pursuing thinness. Typically, all foods considered fattening, such as carbohydrates and fats, are banned and bulky, low-calorie foods, such as vegetables and fruit, are allowed.

If the individual exists in a state of starvation for a sufficient length of time, the rigid diet may be broken by a desperate eating binge in which everything and anything available is eaten rapidly. In such an episode food may be eaten straight from tins, insufficiently defrosted from the freezer – whatever is to hand, without thought as to its calorie content or appetizing nature. The food is usually eaten extremely quickly, without being enjoyed and frequently without being properly chewed and digested. This kind of episode is called a bulimic episode, as it is followed by feelings of self-loathing and disgust, which prompt the person to rid herself of the food as quickly as possible. She may do this by self-induced vomiting or by taking a large quantity of laxatives, in order to get rid of the food before the calories have been absorbed. Between 40 and 50 per cent of people with AN experience bulimic episodes.

Bulimic AN is a different story from ‘pure’, abstinent anorexia, and is characterized by feelings of guilt, self-disgust and failure. It is also self-abusive, in that the person often regards the post-binge purging as a form of self-punishment. In contrast to the control and perfectionism of AN, BN tends to be associated with impulsivity, and can include or lead to such behaviors as alcohol or drug abuse, sexual promiscuity or stealing. The feelings of self-disgust experienced by the person with BN may reach the extremes of self-harm, such as body-cutting or burning, and may prompt suicide attempts. The behavior of the person with BN, characterized by high impulsivity, emotional instability, explosive relationships and self-destructive tendencies, is similar to the condition of borderline personality disorder.

The concept of addiction is also closely related to the behavior of the person with BN, as the binges are compulsive and secretive, and the individual comes to rely on them as a comfort, or escape hatch, when they find themselves unable to deal with life’s problems.

I had to have a ‘perfect’ day, in terms of eating, or it would end with a binge. Some days I knew in the morning that I would go home and do it, and I would stop in at the supermarket on the way home to stock up. Everything would be ready-to-eat, and I would buy things that normally I would never allow myself, things like pies, chocolate and always ice-cream. I always made sure I had a 2 litre bottle of lemonade as well, as it made the process of vomiting much easier afterwards. While I was eating I felt kind of high, but as I began to feel full to bursting point, the panic would set in. As soon as the binge was finished, I would go to the bathroom and begin to make myself sick. This involved putting my fingers down my throat, and sometimes taking gulps of water from the tap to help the food come up. When I was done, I felt quite light-headed and sort of cleansed.

Lucy

The two forms of AN, abstinent and bulimic, are not mutually exclusive. As mentioned, the abstainer will occasionally have bouts of bingeing and the person with BN will have episodes of self-starvation. However, if the patient is more bulimic than abstinent, her body weight will be nearer to normal than that of the abstainer, and she will therefore find it easy to keep the behavior secret. In pursuit of this secrecy, people with BN often purchase the food they intend to binge on separately, and hide the evidence from others. Those with abstinent AN are far easier to detect as their bodies show the symptoms of the illness.

Whatever the primary behavior type, at the core of AN is the individual’s fear of gaining weight, and her efforts to avoid this.

Although the ‘classical’ picture of AN is now widely recognized, the disorder often merges into and overlaps with many other psychological conditions. For more information on these, including those mentioned in the following paragraphs, see other books in this series listed in the Useful Books section on p. 241.

When using the term ‘depression’ here, we are not just referring to everyday sadness and unhappiness. The qualities which go to make up what psychiatrists would call a depressive illness or major depressive disorder include persistent low mood or lack of feelings; sleep disturbance; lack of energy; poor memory; poor concentration; feelings of guilt and worthlessness; and a very negative or pessimistic view of yourself, your past and the world around you. Sufferers say they feel empty or dead inside; it is as though their feelings were paralyzed. Many cultures have a quite different set of words to describe this feeling – in the nineteenth century we used the word ‘melancholia’ – but unfortunately in contemporary Western society we use the word ‘depression’ to cover a wide range of feelings from mild, brief unhappiness to persistent and all-embracing despair.

Low mood, persistent depression and depressive illness often coexist with AN. The relationship is a complex one. Some people quite rapidly get ‘dieting depression’ when they go on a strict diet – indeed, their mood may drop even before any significant weight loss has occurred. Others get the opposite reaction and may experience a marked sense of elation, increased energy and well-being when they first embark on a diet. At some stage almost all people who are in a state of severe starvation will get depressed. Sometimes this is a gradual process, the depression getting deeper and deeper the more marked the weight loss; sometimes it can be quite sudden. I have one patient who seems to be fine until her weight drops below 40kg (88lb). At 42kg (93lb) she can be cheerful, bubbly and full of energy, but at 39 kg (86lb) she is physically and mentally slowed up, has a very pessimistic view of herself and the world around her, and experiences major symptoms of depression. This depression does not respond to anti-depressant drugs or to psychotherapy but is dispelled by a small amount of weight gain.

In other individuals the weight loss can be extremely severe before depression sets in. Very occasionally, individuals who have starved themselves close to the point of death (23–4kg or 50–3lb) still appear quite cheerful. However, in these individuals the apparently happy mood is often very brittle and may hide a great deal of personal pain and distress. In these cases there seems a clear relationship between low mood and the starvation state.

In some individuals it appears that the depression may have come first. Many women whose AN began in adolescence can in retrospect identify a clear period of depression over a few weeks or months before they started dieting. It was almost as though their dieting was a response to their low mood, and sometimes a partial solution to it. When they came for treatment there was no sign of the depression at all; but when they recovered from their AN either they were able to remember and recognize the depressive period they’d had, or, more distressingly, their depression came back when they gave up their anorexic coping mechanisms.

A third pattern is when depression occurs after many years of AN symptoms. Depression is a common occurrence in many chronic and disabling disorders, and it is difficult to establish whether there is anything special or different about the depression that occurs in chronic AN compared with that which may occur in someone with a chronic physical condition such as rheumatoid arthritis, epilepsy or diabetes. The depression may be a result of having to cope with a serious disabling disorder which affects all aspects of your life.

In a fourth situation AN and depression occur simultaneously. This is particularly distressing because the individual is beset at the same time by two equally disabling and painful conditions. One positive aspect, however, is that people in this group do tend to seek help early.

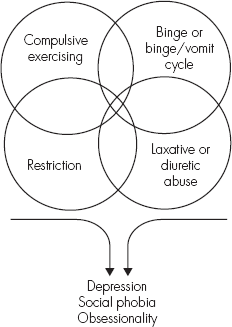

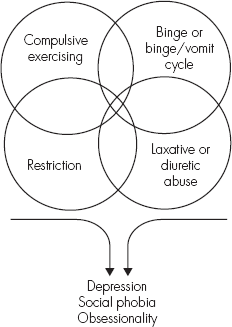

Figure 3.1 Elements of AN and other psychological symptoms

An obsession is a repeated, intrusive thought that comes into your mind against your will, and that is difficult or impossible to resist. Usually there is a need to do or think something to neutralize or counteract the thought. Compulsions are the rituals that people carry out in response to their obsessional thoughts. Examples are counting, touching, washing and checking rituals. Obsessional thoughts may revolve around themes such as fear of contamination, fear of being harmed or harming others, the need for order or symmetry, or the need to feel clean or to feel things are ‘just right’. These thoughts are not hallucinations. Obsessional individuals do not hear voices; they know the thoughts they have are their own, even though they feel alienated from them and do their best to resist them.

AN and obsessive–compulsive disorder overlap in two areas. First, many of the core symptoms of AN have a definite obsessional quality to them. The repeated thoughts about food, fatness, body shape and size fit all the criteria for obsessional symptoms. The case of Richard is an example.

Richard was a 19-year-old student with a three-year history of AN. His diet had become extremely restricted so that he could only eat white food off large white plates. The plates had to be scrupulously clean and he had to wash them several times before they could be used; no one else could touch the plate. His main diet consisted of boiled white fish. He would boil the fish in plain unsalted water and stand over the pan with a paper towel, dabbing the globules of oil and fat which rose to the surface. The fish would be boiled until it was mush; then it would be ‘safe’ to eat. Although much of his behavior was about avoiding calories, eating mainly protein and particularly avoiding fat, there was a definite ‘magical’, ritualistic quality to it. The whiteness clearly symbolized purity and cleanliness, and was seen as good. He was not particularly afraid of germs; it was just that the food had to feel and look right before he could eat it. Richard’s obsessionality got worse the thinner he got, and largely disappeared when he recovered from his AN.

Second, about half of all individuals with AN develop obsessional thoughts in areas not directly related to food. They have quite separate checking, counting or touching rituals or a repeated need for order, symmetry or having things feel ‘just right’. The case of Jane is an example.

Jane is a 32-year-old woman who has clear symptoms of both AN and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Many of her obsessions, but not all of them, revolve around food. She takes three hours to prepare her evening meal, even though she ends up eating virtually the same every night. She has to weigh and check things repeatedly, and the meal has to feel and look just right before she can eat it. She is constantly on the move; while she is preparing food she goes backwards and forwards between the kitchen and the living room, deliberately only taking one thing at a time. When she moves round the kitchen she always takes the longest distance between two points. These are ways of keeping moving and burning off calories. She lives in a second-floor flat and has to climb up and down the stairs at least 10 times each evening before she can feel satisfied. She will always find a rational reason for this but knows that she is quite driven. She eventually sits down exhausted about 9 p.m. in front of the TV to eat her meal and allows herself an hour of relaxation.

Jane’s other obsessions include cleanliness and tidiness. She cleans the house every day when she gets home from work and tidies it up, even though she lives alone and the room has remained untouched since she left it that morning. Some of these activities obviously also involve exercise, but others are to do with order and symmetry: these include having all the book spines on the book shelf even, the magazines neatly arranged, the ornaments on the mantelpiece positioned in an exactly symmetrical way and the pictures all checked to see that they are straight.

Jane’s hands are red, raw and scaly from repeated washing, and the cuticles around her fingernails are all inflamed.

Jane has no time for any social or recreational activities; work, food preparation, exercising and cleaning take up 19 hours a day. She gets approximately five hours sleep.

For a person to be diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder requires more than simply being obsessed or preoccupied. People may be obsessed with books or model railways or animal welfare and spend a great deal of time thinking about their subject; however, in most cases there is no sense of resistance, the activities are often pleasurable or give a sense of satisfaction, and there is no sense that by carrying out some sort of ritual you will magically alter what has been done.

Anxiety is a very common symptom in individuals with AN and has multiple triggers. There is anxiety about food, eating, body shape, the need to exercise and feelings of being out of control.

More specific anxiety symptoms can be seen in a number of areas:

For more information on anxiety disorders and how to cope with them, see the books in this series by Helen Kennerley, Overcoming Anxiety, and Gillian Butler, Overcoming Social Anxiety and Shyness.