Chapter 2 described a long list of difficulties associated with perfectionism, including problems with work, studying, socializing and feelings of low mood, anxiety and fatigue. If perfectionism were all negative, it would be relatively easy to change. We know, on the contrary, that perfectionism can be difficult to change – and an important reason for this is that it can serve many positive functions at the same time as causing so many problems.

Aamina: Why be average if you can be the best?

Aamina, aged 45, is a highly attractive successful businesswoman. She runs her own company and is widely admired. She has won numerous awards for her innovative approach to business and for encouraging women in the workplace. Her personal motto is ‘Nothing’s impossible, if you try.’ Although she has been in a number of relationships, she generally found these unsatisfactory as her partners typically wanted to spend more time with her than she felt able to give without it affecting her work negatively. She earns a six-figure salary, has a high-flying lifestyle and enjoys many aspects of her work. At night, however, she is plagued by thoughts about all that she has not done at work, and how her company could have been bigger and better if only she had acted differently. She feels a fraud for winning the awards, perceiving that she could have done more than she had and to a higher standard. She feels that her work has been superficial and lacks meaning as she is not helping the world’s poor. She acknowledges that nothing she achieves will ever be good enough for her, and is fearful of a life of hard work without any sense of personal satisfaction. She feels a ‘fraud’ and fears failure intensely.

It is clear that although Aamina’s perfectionism is causing her real problems, it would be extremely difficult for her to change. There are practical reasons for her to keep working – her lifestyle depends on a high income and jeopardizing that would pose great challenges. Also, she is likely to think that changing her perfectionism would have a negative impact on her success at work – and yet, although this sounds as if it would obviously be the case, in fact it isn’t obvious at all. This book is about testing such assumptions – in Aamina’s case, finding out exactly what would happen if she were less perfectionist and more flexible. Could she have her cake (her success) and eat it too (flexibility)? She has little else in her life apart from her work and so it would be very difficult to change anything that she might regard as potentially causing her difficulties in this area. Her hard work and objective success are socially reinforced by admiration from her colleagues and the public acknowledgment of awards. Although she may dismiss these in the privacy of her own mind at night, they are also very difficult for her to give up.

Many people with perfectionism fear mediocrity. They regard themselves as achieving what they do because they strive. Many will say, ‘I do OK not because I’m clever but because I work hard.’ Many believe that they are less able than others but that they can compensate and hide this by working hard. This may be true; but it may not and it is absolutely, fundamentally important to find out what the real situation is and what would happen if changes were made.

Despite the anguish that such striving can bring, the thought of not striving and potentially achieving less brings more anguish since the self-worth of perfectionists is so dependent on pushing themselves as hard as possible and doing well. People with perfectionism are caught between a rock and a hard place – the perfectionism is causing many problems but it is bringing with it the rewards that come with striving and pursuing high standards. These rewards are often social and include prizes and praise. Reports from school often rate the effort that children put into their projects in addition to performance. The mother who manages to look immaculate while also maintaining an immaculate home is frequently the object of admiration at the school gates, attracting comments such as ‘I don’t know how she does it.’ Working hard is socially condoned; the opposite end of the spectrum – laziness – is not. However, there is a middle ground.

In addition to the social rewards, there are financial rewards for working hard and success in the work arena; and there are positive internal rewards as well. On the one hand, perfectionism brings with it social isolation and takes up a huge amount of time. On the other, it can serve the function of avoidance for those who may not enjoy socializing and who recoil from company. Keeping a perfect home, practising a musical instrument, training hard – all mean that the person doesn’t have time to socialize with others or to engage in other tasks that they may not find valuable or enjoyable. Being focused on one task can give a sense of control and predictability and, particularly in the case of perfectionism and eating disorders, a sense of order in one’s life.

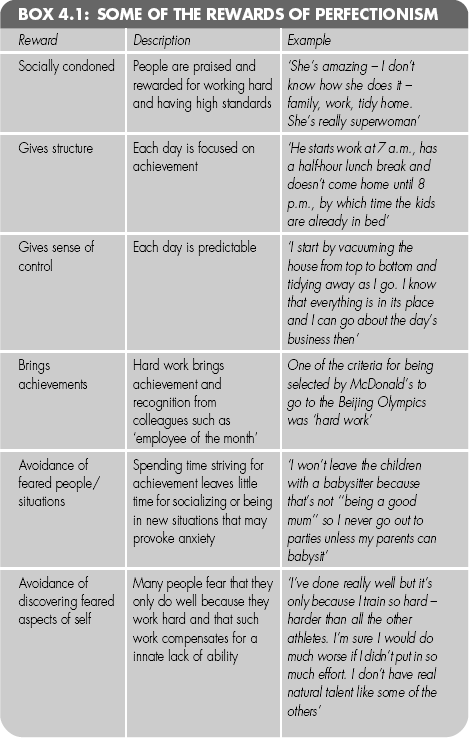

The positive aspects of perfectionism are shown in Box 4.1 overleaf. Not all people will experience every positive aspect, but the range of positive rewards illustrates why perfectionism can be so difficult to change.

In 2001 we spent a great deal of time trying to work out the nature of perfectionism and why it persists. Why couldn’t people just weigh up the advantages and disadvantages of being a perfectionist, decide that the disadvantages outweighed the advantages and change? The answer is: it isn’t as simple as that. It isn’t a straightforward evaluation of pros and cons, leading to the logical conclusion that change is necessary and the making of that change. Part of the reason why it is difficult to change is that the perfectionist person’s self-evaluation is overly dependent on striving and achievement. Another part of the reason is the strengths of the positive benefits described above. Yet another part of the reason is fear – fear of failure, fear of change and fear of discovery.

We do not underestimate how hard it can be to change; but we also know how hard it is not to change, to go on being a perfectionist. This book is about encouraging you to find out what happens if you make small changes – does the worst happen or do you get some pleasant surprises? Take the example of Leung, who discovered that if he ate regularly and slept regularly rather than working through mealtimes and sleeping only when he felt he had completed enough work in the evening, his grades actually improved. He found out that his previous belief that he wasn’t naturally clever so needed to work hard was an over-simplification of the real situation. He did better if he put some effort into the task, but he didn’t do even better if he went over the top with his work.

Figure 4.1 Why perfectionism persists

There are other important reasons why change is so difficult and why perfectionism persists. Various processes lock people into the cycle of perfectionism, and these are self-perpetuating and hard to break. We put them into a diagram to help people understand why perfectionism persists. The diagram is adapted according to the particular needs of each individual, but a general framework is shown in Figure 4.1. This focuses on the way of thinking, feeling and behaving that keep perfectionism going.

We suggest that people get locked into perfectionism for the following reasons:

The cognitive behavioral model of perfectionism is a starting point for understanding what is keeping perfectionism going. The rules, behaviors and thinking biases that characterize perfectionism and keep you locked into a cycle are all interrelated. This means that if you make a change in one area, you will automatically see changes in other areas too. The first step to changing your perfectionism is understanding what is keeping it going and personalizing the model to reflect your own situation. Chapter 5 and Section 7.1 will help you do this.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE