AN is rarely if ever caused by any one single factor – there are nearly always several factors involved – and each individual with AN is unique. This means that there are many possible contributing causes for the condition in any one person. This chapter sets out explanations generated by different schools of thought. You may find that one or more of these applies to you, or triggers thoughts of other factors which are unique to you.

It is useful to look at the causes of AN in three categories:

A single factor may act in all three ways, but it is often the case that quite separate factors are involved in the three stages.

It is important to understand AN can be caused by factors from within (biological or psychological), from experience or from the family environment. AN can not be accounted for by one over-arching theory, but only by an approach which considers life experiences in all areas.

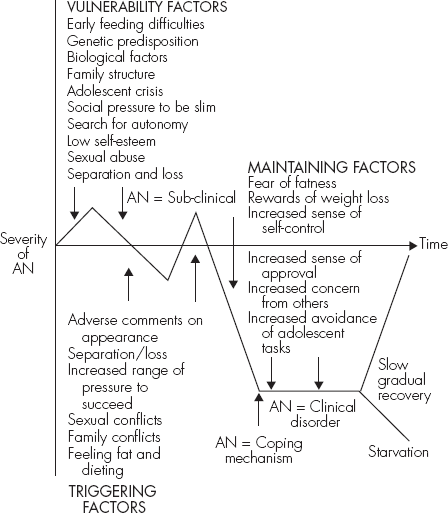

Figure 5.1 Factors that contribute to the onset and maintenance of AN

While AN is distinct from other eating disorders such as BN or obesity, the themes across the three are similar: the use of food, shape and weight as a means of expressing and or controlling distress.

Many children develop early feeding difficulties, for a wide variety of reasons. It could be that the child is a naturally picky eater; or that the parent who is responsible for feeding, usually the mother, has a strained relationship with food herself, or has a limited knowledge of how to feed a child appropriately.

There is now good evidence to indicate that psychiatric disorders in parents have the potential to interfere with their childrearing skills and the emotional development of their children. Eating disorders are an important type of psychiatric disorder prevalent in women of childbearing age. The effect of pregnancy on a woman’s body may have a lot to do with this. After all, there are few conditions which cause such rapid and radical change in body weight and shape, and this can trigger off a fear of fatness where it previously did not exist. Many young mothers experience a slump in self-esteem because of weight gain during pregnancy, and this can often be the beginning of years of dieting. Slimming magazines recount tale upon tale of women who struggled for years with their weight and date the beginning of their weight gain back to their first pregnancy. Of course, concerns about body weight may have existed long before a pregnancy.

If a mother has an eating disorder it can affect her child in a number of ways. If she is preoccupied with her own body weight to the extent that she rarely considers her own needs when it comes to eating – that is, if she eats what and when she feels she ‘should’, rather than eating when she is hungry – this may reduce her sensitivity to her infant’s needs. In short, she may have lost the ability to recognize natural feeding needs. Those who suffer from an eating disorder also frequently have difficulties in their interpersonal relationships, which can extend to the relationships that they have with their children.

In adolescence, the child can become very vulnerable to cultural ideals. Supermodels such as Kate Moss and Jodie Kidd, who are extremely thin yet considered extremely attractive, may make a teenage girl, struggling to come to terms with budding breasts and the remains of baby fat, feel overweight and ungainly by comparison. A parent who is equally unhappy with his or her own ‘non-ideal’ body shape may reinforce the teenager’s concerns. If the parent has very strong attitudes regarding shape, weight and diet, s/he may influence the child’s attitude tremendously. Comments suggesting that the child is too fat or too greedy may cause great distress. Problems can also arise if the child models his or her behavior on a parent who has an eating disorder.

One of the difficulties in examining childhood eating patterns and attitudes to body weight is that this is mostly done in retrospect, when the individual has matured and already developed an eating disorder. From this perspective it is often tempting to look back and exaggerate any feeding abnormalities in childhood. Such methods of enquiry tend to lack rigour and fail to generate scientifically reliable data.

There is a tendency for eating disorders, like other psychiatric disorders, to cluster in families. The children of parents with an eating disorder have been found to be much more at risk of developing a similar disorder than those whose parents had a healthy attitude toward food. While the findings are nowhere near specific enough to distinguish environmental causes (i.e. learned habits) from genetic (i.e. inherited) causes, there is more to suggest that the genetic explanation is the stronger one.

Studies have shown that there is a genetic predisposition to AN and other eating disorders. One study of twins showed that if one of a pair of monozygotic (identical) twins developed AN, then the other was four to five times more likely to develop the disorder than in the case of nonidentical twins. This finding, along with the evidence which shows that first-degree relatives (children/parents/siblings) of patients with AN are at an increased risk of developing the condition compared to the general population, is firm evidence that there is a strong genetic predisposition toward development of this disorder.

As a species, we are very well adapted to starvation. Consider a situation such as a famine. For the famine-struck society to survive, there has to be at least a small group, particularly of women, who can cope with starvation to the extent that they survive for many months, even years, to ensure that children can be born and cared for. There must also be a group of people whose energy levels are maintained, and who respond to starvation by becoming over-active. These are the individuals who can plan and perform essential tasks despite their weakened physical state: search for food, rebuild shelters, sow and harvest crops. It also makes sense, biologically speaking, to have a group of people who become inactive and die fairly quickly, thus reducing demand on dwindling food stocks.

Starvation has a radical effect on the chemical levels in the brain, particularly levels of serotonin, which stimulates hunger and craving for particular foodstuffs and is related to the development of obsessionality. Generally speaking, serotonin is released in the brain when we start eating. The surge of serotonin, which occurs particularly with a high-carbohydrate meal, is important in producing feelings of fullness and the desire to stop eating. On the other hand, very low levels of serotonin produce hunger and sometimes restlessness. It is interesting to note that serotonin levels drop before ovulation; this may go some way toward explaining why some women have increased food cravings at this time.

Other chemical messengers stimulated by starvation come from the stomach and intestines. An important one is cholecystokinin (CCK). Low levels of CCK produce feelings of hunger and craving.

The stereotype of the ‘anorexic’ family is a negative one, in which the parents are overly protective and interfering and have very high expectations of their offspring. This is a somewhat misleading model, and many differences claimed to exist between the so-called ‘normal’ and the ‘anorexic’ family have been shown not to apply consistently. However, there are some features of family life which do seem to relate to the development of anorexia. These are:

Adolescence is the peak time for the onset of AN. It is in the early teens that a person develops their sense of identity and their views on the world around them. This can be a period of great uncertainty in terms of academic ability, sexuality and social skills. Severe weight loss can halt or delay development in all three areas.

The period of transition between childhood and adulthood is a very tricky one. It is an age when the desire to be older and more mature becomes very powerful, as do the seductions of adulthood (as viewed from a young perspective) such as drinking, having sex and making money. This frantic desire to take on the mantle of adulthood can result in teenagers ‘growing up too quickly’, or behaving in ways for which they are, as yet, emotionally unsuited, such as embarking on sexual relationships at a point where they are still uncomfortable with the physical changes wrought by puberty. Alternatively, teenagers may find it enormously difficult to let childhood go, not just because they are apprehensive about the idea of being an adult, but also because those around them, particularly parents, may prefer them to remain childlike.

It is an important part of the growing-up process that young people can take ‘risks’, such as asking someone for a date and therefore risking rejection. It is also important that they are able to do this against the backdrop of a secure home environment, where there are no risks. This risk-taking is essential as it enables the individual to establish a degree of self-reliance, to develop confidence and engage with the world in a non-fearful way. If the individual is prevented from acting independently and self-sufficiently, most commonly by over-protective parenting, their progress may be even more difficult than it would be normally.

Of course, on the part of the vast majority of parents such over-protective behavior is not malicious interference. Usually they just want the best for their child, and feel that this can only be achieved by exerting external control over their lives, perhaps in the form of pushing them academically and/or athletically. Often this is accompanied by the opinion that time spent with friends and boyfriends is wasted time, and so these activities are dismissed as trivial or actively disapproved of. Initially, a child will toe the line in order to avoid censure from or conflict with parents. However, if the child continues to behave this way, accepting parental dictates wholesale and doing the utmost to avoid conflict, feelings of pressure and entrapment can develop. The child’s urge is to say ‘no’, to make her own demands, to rebel. If she feels that she cannot articulate these feelings then she may, subconsciously, seek other ways of saying ‘no’.

One of these ways is by refusing to eat. The put-upon adolescent comes to see her body weight as the only arena in her life over which she can exert any control. Losing weight can provide an enormous feeling of relief as it provides concrete proof of that control. It can also become a powerful statement of rejection directed at the family and home life. Losing weight can generate feelings of empowerment and superiority in an individual suffering from low self-esteem.

The Western ideal of feminine beauty has been a slender one since the 1920s. Back then, women smoked, took amphetamines and exercised in order to achieve the boyish figure that was currently in vogue. However, this mania for fashionability was pretty much restricted to the upper classes. Nowadays every level of society is aware of fashion. Magazines show us pictures of Liz Hurley in skin-tight dresses, while newspaper columns detail the extraordinarily strict dietary habits of Madonna and Claudia Schiffer. We are bombarded with images of a glamorous world that does not tolerate imperfection, particularly the avoidable imperfection of fatness. Hollywood film companies are so determined to provide images of female perfection that they often employ body doubles for nude scenes; actresses routinely have bits of their bodies airbrushed out of the final cut if they are deemed too plump. A recent American survey provided the shocking finding that, so phobic has society become about fatness, men would rather date a heroin addict than an overweight woman.

Little wonder, then, that young people growing up in this environment become obsessive about their weight and feel that, above all other aspects of themselves, this is the key to attractiveness. Magazines may very well advise on the need for adequate vitamin intake and healthy attitudes, but they will invariably accompany this sensible advice with pictures of stick-thin models in their fashion spreads. Though this may seem trivial from an adult perspective, it is necessary to remember that for an adolescent the issue of attractiveness is one of paramount importance. Therefore, the urge to be thin can outweigh all other aspirations.

For women there is an added complication. While film stars and celebrities have the legs of teenagers, they are also voluptuous. For most women, this combination is elusive. When they diet, their breasts reduce and they appear more boyish. Without recourse to surgery, they are caught between two ideals of beauty. This reflects many women’s experience of life as well. They still feel caught between the need to be a successful, independent career woman and an attractive partner and loving, nurturing mother. This can be very confusing and distressing, and thus the pursuit of thinness, above everything else, can be something of a relief. Some women can convince themselves, with a helping hand from media-generated ideals, that being slim will solve all their problems, and iron out all contradictions.

The trouble is that the only problem thinness solves is the ‘problem’ of fatness. Being slender will not make any other area of life easier. It will not make you good at your job, popular or more loved. However, lack of ‘results’ in these other areas can often propel the person to pursue thinness all the more obsessively, long after they have achieved their original goal, as they have become so entrenched in the notion that thinness can solve everything. Many non-anorexics suffer from this belief, and throughout their lives devote time, effort and money to dieting and exercise regimes that serve only to undermine their confidence by not delivering them from their perceived state of imperfection. However, for the person vulnerable to AN this can be the point at which they become divorced from reality and see weight loss as the ultimate objective, bar none.

When we are children we are generally content to be seen as part of a family unit and to be identified as such. When we reach adolescence, however, the great pursuit of autonomy begins. This is a natural and essential rite of passage, and for most people it goes relatively smoothly. Of course, there will be family showdowns about clothes and haircuts, suitable friends and career ambitions, but most families are able to adjust to change and give burgeoning personalities enough breathing space to grow. It is when the family is unable to adjust that problems can arise.

For instance, a family that prides itself on producing lawyers may react badly against a teenager who has determined that she will go to veterinary college. They may withdraw financial and emotional support in order to bully the child into following the family tradition. The outcome can go either of two ways. The child may react by leaving the family unit and doing her own thing, or buckle under family pressure, do as she’s told and develop a sense of resentment. In the latter case, where the young student feels that she has no control over the future and her identity, she may attempt to establish her autonomy in another way. Eating is one of the classic ways of doing this, as it is so central to family life. By refusing to eat, or developing peculiar or picky habits, the youngster is demonstrating autonomy in front of the family.

This desire for autonomy does not rear its head only in adolescence. It can arise if a sibling feels herself to be in the shadow of a more ‘successful’ brother or sister, indeed is perhaps often referred to as such. The desire to be thin may arise from a need to establish an identity that is other than that of ‘less successful sibling’. It can also arise if a woman finds herself submerged in the role of mother and wife, and seeks to be seen as an individual rather than just an appendage of her husband and children.

However it happens, the pursuit of thinness is often based on a need to be seen as an individual, and to feel that self-will can be exercised, if only in one area of life. Thus the beleaguered adolescent who refuses to finish her lunch may be someone who is screaming to be allowed her autonomy but can find no other outlet for it.

My father was determined that I went to his old university and studied the same subjects as he had, namely physics and maths. I didn’t know how to say no to him. In fact, no one in my family knew how to do that. I did as I was told, even though I had wanted to study English literature and it was actually my best subject. The summer before I left home to begin university, we went on a family holiday to Belgium, and it was then that I began not eating. It became like a game, to see how much I could get away with not eating each mealtime. I don’t remember feeling hungry or lethargic. I think the fact that I was the one in charge gave me a real buzz. When we got home and I found that I’d lost nearly three-quarters of a stone [9lbs], I felt great. It was the first time I really felt like I was doing something that I wanted to do.

Karen

Low self-esteem can run in families. Parents with a low opinion of themselves may pass it on to their children by comparing them unfavourably to other people’s offspring. This can result in children growing up with the belief that they are not as worthy as others and having little self-confidence. Low self-esteem can develop in adolescence, when young people invariably agonize over how they match up to others and become self-critical, or when crises, such as loss of occupation or desertion by a partner, occur. Low self-esteem can be dangerous: it makes people very vulnerable, prompting them to accept relationships that may be bullying and unhealthy, or poorly paid jobs where they are put upon by others who see their lack of confidence and exploit it. It can also lead to depression, to a recurrence of illnesses and to a severely reduced enjoyment of life.

When low self-esteem is recognized as the root of your problems, there are ways to deal with it. There are excellent self-help guides (for example, the book by Melanie Fennell in this series; for details see the ‘Useful Books’ section on p. 241), courses and therapy sessions which can go a great way to changing individuals’ perception of themselves. However, when low self-esteem is not identified as the problem, and the person continues to labour under the notion that they simply do not match up to others, the solutions sought can be unhealthy in the extreme. Alcoholism is one example. Many alcoholics turn to drink as a way of masking their negative feelings about themselves and, in a sense, escaping from themselves. AN is another. By unloading all those self-critical thoughts on to body image, a person can convince herself that, if only she lost a stone, two stones, three stones, she would become a better and happier person.

As she loses weight, she will feel a sense of achievement which will heighten her self-esteem. If the weight loss continues after the target weight has been achieved, it may be that self-esteem is now so strongly identified with weight loss that to gain weight – even if it did not rise above the original target minimum – would be severely detrimental to it. Many people with AN know that, by starving themselves, they are not tackling the real problems of their lives, but have become so dependent on extreme thinness as a way of bolstering their self-esteem that they cannot make the break from it. This is not to say that within their emaciated bodies they are bursting with confidence; quite the reverse, in fact. The problem is that, as they see it, to gain weight would make them feel even worse.

Studies of the histories of people with eating disorders have found a much higher rate of sexual abuse than among women with no psychological problem. However, the rate of such abuse was no higher than among women with other psychological disturbances, such as depression. Sexual abuse therefore seems to be associated with psychological disturbance in general, rather than with eating disorders in particular.

There has been much debate recently as to whether women who have experienced sexual abuse or been coerced into unwanted sexual experiences are more likely to develop difficulties associated with eating. So far the results have been inconclusive.

For some women, the link between sexual abuse and eating disorders is quite clear. Some sexual abuse victims feel that they have lost control of their lives, and that the eating disorder re-establishes some form of control, however negative. Some even choose to alter their body shape to the extent that they reduce their desirability and therefore stave off further sexual approaches. Others speak of guilt, disgust and self-hatred, and use the eating disorder as a form of self-punishment. An important feature common to the women studied is that their lives had many other major problems and upheavals occurring simultaneously. Hence it is likely that the eating disorders were the result of cumulative problems rather than the single factor of abuse.

It has also been discovered that the eating disorder may have a functional purpose, that is, it is used in an attempt to solve a problem. For example, by developing an eating disorder, a person may be trying to punish the abusive parent, or the parent who failed to protect them adequately. In this instance, the changes in eating patterns and consequent eating disorder are a means of causing disruption and of attaining control. In short, the eating disorder is a stick with which to beat those who are felt to be to blame.

Certainly, for those who have suffered sexual abuse and are now experiencing eating difficulties, examining and working with their feelings relating to abuse can be helpful. A useful resource for those in this situation may be the book in this series on Overcoming Childhood Trauma (for details see the ‘Useful Books’ section on p. 241).

Few things in life have the devastating impact of permanent loss or separation. Losing a parent, a close friend, even a beloved family pet, can turn an individual’s world upside down. Death is particularly hard as most of us are without a mechanism to deal with it, especially if we have no religious faith to provide us with some form of comfort, and as those around us are suffering too. For a child it can be even worse, as a death throws up new questions of their own mortality and that of the people around them. Many children who lose one parent become morbidly obsessed with the idea that they will lose the other.

When we lose someone close to us, we experience enormous sorrow which can permeate our general consciousness for a time and lead to depression. A common feature of depression is loss of appetite, and so weight loss is fairly common in this situation. For most people, even children, this is a temporary state, and body weight will return to normal during the process of coming to terms with the loss. Even so, the journey of grief and mourning can be a long and hard one, requiring us to acknowledge our emotional needs and dependencies, and to recognize our own vulnerability. For some, the process of grieving seems an impossible task, perhaps because they feel that the pain will be too great if they give into it or perhaps because they believe that no one fully understands their feelings. They may use food as a means of numbing themselves to emotional pain. Starvation can cause this state of numbness and protect the individual by delaying the active process of grief and mourning. Because eating will restore normal feelings, they may choose to continue with the starvation. Another way of deflecting pain is by bingeing food and then purging the body of it. Eating will provide a sense of comfort and the subsequent feelings of self-loathing and desire to purge the body will occupy the mind and stave off other feelings. In this sense, BN can be seen as a way of crowding out unwanted emotions.

In recent years increasing amounts of evidence have been gathered to support the clinical observation that children and adolescents exposed to undesirable events are at a significantly increased risk of developing depression and other forms of psychopathology, including eating disorders. The most difficult kind of events to deal with are those involving the loss of someone close. This degree of crisis can also trigger adults toward depression and, in some cases, AN.

There are many reasons why a person may be prompted to lose weight and subsequently develop AN. It may be that they are influenced by external pressure to be slim, or by a desire to assert their autonomy within a restrictive family structure. They may be reacting against sexual abuse or the loss of a loved one. Whatever the reasons, it is important to remember at this stage that not all diets result in AN and not all cases of AN derive from a desire to fit into size 8 jeans.

Evidence suggests that self-esteem is one of the most critical factors in the development of the disorder. The life circumstances in which AN occurs are very varied. They may be fraught and difficult, with the vulnerable individual feeling under pressure from parents, put upon by others, or restricted in her future choices. Alternatively, these circumstances may be excellent, with supportive family, unconditional love and great prospects for the future. The common element is that the individual who develops AN, for whatever reason, experiences chronically low self-esteem.

Personality type is also an important factor. Where one personality type reacts to adolescent conflict by indulging in drug-taking or sexual activity, another personality type may exercise self-control, in the form of abstaining from food.

Finally, an inability to cope with change, be it in family structure, body shape or approaching adulthood, can make an individual very vulnerable to the development of AN, as can a similar inability in those around her.

The most important thing to be aware of is that no two cases of AN, or any other eating disorder, are exactly alike, and no one factor is at the root of the condition. It is also important to be aware of the fact that AN creates a state of mind that actually maintains the disease. We shall explore this point further in the final section of this chapter.

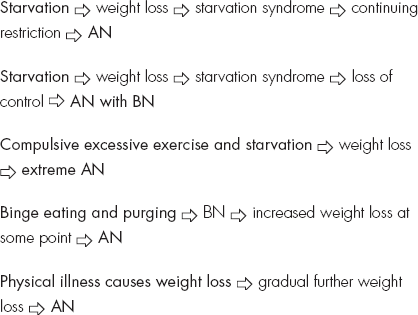

The second stage in the development of AN consists of the period between the establishment in a vulnerable individual of a behavioral precursor, such as dieting, through to the establishment of AN in its own right. Some of the factors described above appear to put the individual more at risk for an eating disorder by increasing the likelihood they may diet. While dieting is the common stage-setter for the disorder of AN, there are still many people who diet, successfully or unsuccessfully, without suffering from AN; the critical issue is what factors combine with a diet to result in AN. One particularly prominent element in this process, as discussed above, is low self-esteem. There is also evidence that particular kinds of adolescent conflict and difficulty, and particular personality types, tend to promote the disorder more than others.

Among the factors which have been considered to precipitate the development of the disorder are those normal to healthy adolescent development, including the onset of puberty, development of relationships (especially with the opposite sex) and leaving home, as well as more distressing events including loss of relatives, illness and others’ negative comments about their appearance. Circumstances which are identified as stressful and capable of making growing up difficult are, predictably, parental psychiatric illness, parental strife, parental loss, disturbance in older siblings and major family crises. Difficulties may arise when an individual is unable to adapt well to change, or when close family or friends are similarly unable to adapt themselves well to the individual’s development and maturity. These failures to adapt are usually inextricably linked, one factor enhancing the effect of another.

There are many factors which contribute to the maintenance of AN once it has become established. The behavior of the person will have changed, and so will the behavior of others close to them; therefore they will now be used to being treated differently by others. Whether or not this change in behavior of the person with AN involves adoption of the ‘sick’ role, the individual with AN will rarely seek help. Self-starvation and the physiological consequences of under-nutrition result in a vicious circle of emotional angst and behavioral disturbance. Both the concrete behavioral pattern and emotional upset must be interrupted and addressed if recovery is to be possible.

Adolescence, as noted above, is a period of transition; it is a time for trying new behavior and gaining new experiences. Withdrawal at this time is common, be it via drug abuse, running away or phobic reactions, and AN may be considered to be such a withdrawal behavior. Once energy and effort have been invested in establishing the disorder, the individual is not going to give it up without a fight. The AN will have become so much a part of their identity and their coping strategy for difficult aspects of their life that it will be difficult for them to envisage the benefits of not having it. Some of the following elements may contribute toward maintenance of the disorder and increase difficulties regarding breaking the pattern:

1 Core features of AN itself, including ‘fear of fatness’.

2 The rewards of weight loss, including feelings of self-control and often approval from others before any severe loss is apparent; also avoidance of the difficult changes which occur in adolescence.

3 Body image distortion, which increases with increasing weight loss.

4 Biological effects of weight loss, which due to the starvation syndrome help to maintain the disorder, including preoccupation with food; decrease of social interest; slowing of gastric emptying, giving feelings of fatness.