The earlier AN is recognized and treated, the quicker and less painful the route to recovery. Delay in recognition can lead to the condition becoming more severe and therefore requiring more intensive and long-term treatment. It is a feature of the condition that individuals with AN are initially vehemently opposed to acknowledging that there is a problem and are therefore reluctant to ask for help. Thus, the average delay between onset of the disorder and its treatment is five years. Effective treatment focuses on helping the individual to take responsibility for their own eating habits, and so depends on the willingness of the person with AN to accept help. This is why forcing the issue, and strong-arming a person with AN into treatment, is unlikely to be successful.

If treatment is never sought, some individuals will develop a very severe form of AN which is resistant to all forms of treatment currently available. Such cases require prolonged and intensive treatment and care. In the one long-term follow-up study published to date, some people recovered even after 12 years of continuous symptoms; but for those who suffered for longer than 12 years, no such recovery occurred. These latter remained either chronic sufferers or died as a result of the disorder. In the light of this finding, it is clear that speed is of the essence when it comes to tackling the disorder.

When seeking treatment for AN, the best place to begin is with your family doctor or GP. If this is not possible, contact your nearest hospital-based general psychiatry or clinical psychology department, or a local community mental health team.

Most people with AN may be successfully treated as outpatients, using some form of counselling approach. This may be undertaken by a psychiatrist, nurse therapist or clinical psychologist: the precise designation does not matter provided the practitioner is adequately trained and experienced. Usually there will be one principal therapist who will see the patient most frequently and liaise between the GP, psychiatrist or clinical psychologist, and other health professionals. Someone seeking help with AN is likely to come into contact with a range of professionals, all with their own particular areas of expertise, working in association with one another. The following are the practitioners most likely to be involved in treating a person with AN.

The GP or family doctor is usually the first professional with whom the person with AN will come into contact, either on her own initiative or through being referred by parents. In many cases, the individual will present her GP with a condition secondary to the disorder, such as depression, cessation of menstruation or constipation. The GP will take a detailed history of the condition with which she has been presented, which will lead her to diagnose the patient as suffering from AN. The stage to which the disorder has progressed will determine whether the doctor decides to refer the patient on to more specialist services or conduct the treatment herself.

In cases where the disorder is not greatly advanced, the doctor may choose to manage the patient within the practice. This may involve a nurse therapist, who can provide basic nutritional and health education, and referral of the individual to a local self-help group. This can be useful in providing information – such as resources and services that are available, including national eating disorder groups, books and dietary advice services – and assisting the acceptance and treatment of the disorder. Initial consultations will alert the person with AN to possibly unrecognized problems or conflicts in her life, encouraging her to redefine what has been troubling her. This may provide a certain degree of comfort, as some people with AN are unaware that they are suffering from a recognized condition and that their thinking is distorted. The individual will be encouraged to see her problem as a psychological one, involving a response, albeit a maladaptive one, to stress or low self-esteem, rather than as one of being in the grip of a slimming or exercise disorder. If marked improvement is not made or the condition continues to worsen, the GP will refer the patient to a specialist.

The physician may be involved in confirming the diagnosis of AN, through the administration of simple but thorough tests analyzing blood and bone density. She will also undertake checks aimed at excluding other physical origins for the marked weight loss, such as diabetes or endocrine disorders.

The primary role of the psychiatrist is in the assessment and diagnosis of the patient’s condition. Once this is done, she will make a decision on what form of treatment is best. The psychiatrist may choose to treat the patient herself, or refer her on to a therapist. If the psychiatrist decides it will be beneficial to prescribe drugs – as part of a comprehensive treatment approach – then she will continue to see the patient to monitor progress. Some people are strongly opposed to the idea of taking drugs as part of their treatment; they may be advised to request treatment by a therapist or clinical psychologist, who will not prescribe drugs. (For more on the use of drugs, see the section on p. 106.)

The clinical psychologist also assesses and diagnoses the patient, but their primary means of treatment is psychological rather than pharmacological. They may offer group or individual therapy, or a combination of both.

A psychotherapist uses long-term exploratory work, usually within a psychodynamic framework. This can involve exploring the patient’s past and uncovering the initial factors contributing to the development of AN. In this form of therapy, the therapist takes an interpretative rather than a directive role, thus allowing the patient to lead the session and explore issues with which she is concerned.

The counsellor is there to provide psychological treatment for the patient. If the counsellor is specialized in a particular area of therapy, such as psychodynamic or cognitive behavior therapy (on the latter, see the section on p. 110 below), they will be particularly effective in that area. An unspecialized counsellor will be experienced in more than one therapy type and will be able to use that which is most suitable for the individual, possibly even using two or more kinds of therapy simultaneously.

The dietician’s role is to assess dietary intake, and to educate the person with AN on the need for a balanced and healthy diet which will provide sufficient nutrients and calories for recovery. They will also encourage the consumption of an expanded range of foods. This is particularly important as people with AN tend to subsist on an ever smaller range of foods that they deem ‘safe’. This may come about because they have a ‘bad’ experience with a particular foodstuff, per haps because it makes them feel bloated and therefore ‘fat’, or because they rule out more and more foods on account of an unacceptably high-calorie content. Expanding the food range helps to dismantle some of the fear and distrust of food.

Dieticians also encourage the use of food diaries, which they will then assess, going through them with the person under treatment. They may see the individual for a one-off treatment, or for a series of time-limited sessions. They will also liaise closely with the primary therapist, whether psychiatrist or clinical psychologist.

Children as young as six have been found to be preoccupied with body shape, weight and dietary behaviors, and there have been reports of an increasing number of prepubescent cases of AN (see Chapter 4). Pediatricians are therefore becoming increasingly aware, when dealing with children who show signs of weight loss or poor physical development, that such symptoms may be indicative of juvenile AN.

Art therapy can be especially helpful where a patient is struggling to express feelings of frustration or pain. It may be used in conjunction with other forms of treatment, or as an independent therapy. It is a welcome alternative to more traditional therapies and can be useful in illuminating important issues.

The occupational therapist uses a variety of strategies, including projective art, relaxation, anxiety management, assertiveness training and psychodrama. A program will be devised to suit the individual patient. For instance, body-oriented exercises may be used to correct body image disturbances, which are particularly characteristic of AN.

Any soundly based program of treatment for AN will have three core objectives:

Where there is a state of malnutrition or starvation, this is treated as a priority. Starvation is known to have profound effects psychologically as well as physically, and can seriously hinder the efficacy of other types of treatment. Some form of psychological treatment is then seen as essential to confront underlying personal, interpersonal and social factors believed to foster and maintain the disorder. This may involve supportive psychotherapy, counselling about eating and dangerous purging habits and, where appropriate, other supports including relaxation, family therapy and marital therapy. The treatment programme is multidimensional, with emphasis on different forms of treatment at different stages of the disorder. One person (the primary therapist) will be the main coordinator to whom the patient can relate and through whom other health professionals liaise.

Of primary importance once weight is at a safe level is the teaching of normal eating patterns. It is important that the individual takes control of her diet as soon as possible and that, with support, she begins to manage a more normal dietary intake.

Drugs are seldom necessary but may be useful if there are complicating additional medical problems (see the section on ‘Drug Treatment’ below).

Treatment as a hospital inpatient is the most intensive form of intervention that may be offered to a person with AN. Cases where hospitalization may be necessary include the following.

Inpatient treatment is often a lengthy process, lasting for 6–12 months; it is intensive and aims to bring about both weight gain and changes in behavior and attitude.

In hospital the individual will first be given the opportunity to take responsibility for her own weight gain, supported by the dietician and nursing team. She may exercise mildly and attend discussion groups with other AN patients to gain insight into the condition; she will also be encouraged to pursue non-food-related interests, such as art, crafts or computer skills.

If this method is unsuccessful at initiating weight gain a more structured treatment plan will be implemented. At its extreme this could involve continual observation or isolation in a single-bedded room, with bed rest until weight has risen beyond the dangerous range. Such measures are necessary at times to counteract the extremes to which people with AN will go to avoid taking nourishment, by hiding or disposing of food, or by vomiting. The fundamental aim at this stage of treatment is to treat the person with AN until she has emerged from a critical state of health; only then is it possible to embark on less aggressive treatment types, such as the various kinds of therapy outlined above.

Admission to hospital has traditionally been the mainstay of treatment for severe AN, but is now the exception rather than the rule, since it carries a number of disadvantages. Removing the person from her everyday environment can be counterproductive and may confirm her identification with the ‘sick role’. It also drastically reduces a person’s sense of control; for someone with AN, who has fostered a sense of control for a long time through not eating, this is a severe blow, and may only strengthen the resolve to achieve further weight loss as soon as she is discharged. For these reasons, hospitalization is primarily of value to preserve life where an individual’s condition has become critical and emergency refeeding and rehydration are required, followed by weight stabilization and prevention of further weight loss.

There are several important features that characterize successful inpatient treatment:

There are a limited number of ways in which emaciated patients can be given the crucial nourishment they need. Intravenous feeding and tube feeding are two examples, but it is preferable if the patient can be encouraged to eat normal foods supplemented with nutritional high-calorie drinks.

Three types of inpatient refeeding programmes are discussed here: behavioral, percutaneous endoscopic gastroscopy and total parenteral hyperalimentation.

The issue of an individual with severe AN refusing treatment is rare, but on the occasions where it does happen the legal system in most countries makes it possible to admit a severely emaciated individual with AN into hospital against her will to protect against the risk of death. The individual with AN may play the system – eating to get out, resisting therapeutic measures and once away continuing in their AN as before. Therefore hospitalization is best avoided unless the patient is especially vulnerable or seeking help.

Hospital treatment as an outpatient is a more convenient and less disruptive form of help. It involves regular attendance as a day-patient for a combination of treatments that may include individual and group therapy, dietary advice, education and social activity. There is an expectation that eating is involved, at least in the form of one communal meal, and food shopping and food preparation are included. One or perhaps two meals are supervised, and participants usually attend on five days a week for as long as necessary.

The advantages of outpatient treatment are that the person with AN can gain weight at her own speed, and so can feel safe and in control. She can take responsibility for eating and, with the support and encouragement of a therapist and dietician, can relearn eating patterns and resume a normal eating regime. This maintenance of the individual’s sense of autonomy is very valuable, and though weight gain is usually slow in outpatients there are pronounced behavioral and attitudinal changes which are sustained for longer periods after discharge than with inpatient treatment.

Drugs play a relatively small part in the treatment of AN, and are seldom used as the primary form of treatment. No drugs will directly affect the course of the illness, though some may be used to relieve certain symptoms: for example, antidepressants may be given to a patient also suffering from depression, just as antibiotics would be given to someone who has an infection. If drugs are used, it is as just one component of a wider treatment program.

Drugs of the following types may be prescribed:

There are several different forms of group therapy for AN, of which the following are the main types.

This focuses on how thought processes are influenced by AN. It is a strongly education-based therapy; those who attend sessions will be taught the basic facts about what AN does to the body and what the physical and psychological symptoms are. This is not a shock therapy, and is not intended to frighten participants; rather, it presents the facts and encourages discussion and the comparing of notes.

Carried out in conjunction with a dietician, this form of therapy concentrates on food issues, such as nutritional needs, meal planning and how to change eating patterns.

Many individuals with AN suffer from a lack of assertiveness, and develop the disease almost as a means of expressing their needs. Learning to assert yourself and to interact socially can be valuable in overcoming the disorder by eliminating the need to express yourself in that way.

Peer group support helps individuals to develop a more realistic attitude in their self-appraisal, and group discussions enable them to investigate their attitudes to body weight and shape in a wider context than that to which they are accustomed, that is, within their own minds. The presence of others when undergoing therapy can be an important stage in the dismantling of the isolation that is such an insidious feature of AN.

For those under 16, involvement of the family in therapy is recommended. Beyond 16 it is up to the individual whether they wish to involve family members or not. In most cases a formal family therapy programme of 6–8 weeks is unnecessary, and more relaxed family counselling is just as effective.

Family counselling involves the parents being seen as a couple, but as a separate unit from their son or daughter with AN. The main aim of this kind of therapy is to help the parents manage the symptoms and behavior of their child, and to help them overcome the sense of helplessness that they feel. Such therapy also allows the individual with AN to ‘come out’ – to be open about their feelings and fears, with the practical support of the therapist and the emotional support of the family.

Research results are so far supportive of this type of treatment, particularly with adolescent AN. It is also proving effective with those just leaving hospital inpatient treatment programs, and those who have failed to respond to an outpatient program.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a form of short-term psychotherapy. Aaron Beck, the father figure of cognitive therapy, coined the term ‘collaborative empiricism’ to describe the nature of the therapeutic enterprise where an individual, closely assisted by a therapist, investigates the basis in reality for a personal hypothesis concerning the world. In other words, both the therapist and the person undergoing therapy examine the truths on which the latter’s worldview is based. It is a very rational form of therapy, in that it guides the individual toward a realistic view of their situation by examining facts rather than feelings.

CBT is not about the therapist arguing with or haranguing the individual, or confronting them with the absurdity of their beliefs. It is about encouraging the individual to collect evidence which may support or refute their beliefs, and then re-evaluating those beliefs in the light of the hard empirical evidence.

A central characteristic of standard cognitive behavioral therapy is its structured, time-limited framework, with each session directed by a previously planned agenda. This can suit the frame of mind typical of the person with AN, who tends to be most comfortable with order and a tight control of events. Cognitive behavioral therapy is non-historical in nature – that is, it deals purely with the present, not the past – and uses a scientific methodology. These two features often appeal to people with AN who are not prepared to delve deep into the past, perhaps because they are not yet ready to face certain deep-rooted issues, but are ready to deal with their disorder.

Individual and therapist work together to identify particular problem areas, for instance, the individual’s belief that she is fat. In her own time, the individual embarks on a fact-finding mission regarding this area. These facts are then used to challenge the negative thought patterns that have arisen, using the cognitive skills learnt in the therapeutic sessions. An important feature of CBT is its open nature, encouraging the individual to view treatment as a series of stages without a pass/fail definition.

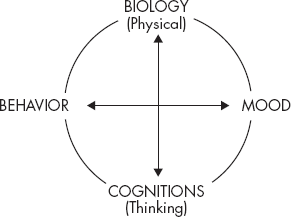

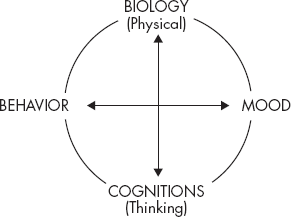

Mood, behavior and thoughts can all affect each other, and in the mind of the person with AN this can result in a vicious circle. A predominant belief in your own fatness can affect mood, making you feel low and panicky, which can affect behavior, making you withdraw from other people, which means that your belief in your own fatness is never challenged, thereby affecting mood and so on. The circular entanglement of mood, thought and behavior is illustrated in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1 Mood, thought and behavior: the vicious circle

During CBT, the person is introduced to this concept as she reveals her negative, self-defeating thoughts. These are often automatic, and may rarely be held up to the light for examination. Such thoughts might include: ‘People are staring at me because I am so fat!’ This thought would be described as a result of a preoccupation with body shape and weight. Discussion would also cover how the presence of this thought influences mood and behavior. Thinking errors would also be looked at. For instance, the belief that: ‘If I lose weight, all my problems will be solved’ is a common thinking error in people with AN – and a dangerous one, as it allows the disease to maintain its grip. CBT is used to challenge errors such as these, which have become rooted in the mind, by seeking rational alternatives.

The self-help manual in Part Two of this book is based on the CBT model, and contains more detailed explanation of the techniques and approaches involved.