In the first chapter of this book we said that unhelpful perfectionism is when your view of yourself is dependent on how well you think you have achieved in areas of life that are important to you, with self-criticism resulting if you think that you have failed to reach your required standards. We know that self-criticism is strongly associated with unhelpful perfectionism. In other words, where one occurs, the other is highly likely to be present. Self-criticism can cause problems in its own right, leading to more perceived daily hassles, more coping by avoidance (that is, rather than trying to deal with or solve the problem, you avoid it and hope it goes away), more negative social interactions and a perception of less social support, and increased levels of depression.

Self-criticism can be seen as the internal critic or bully, or the voice in your head that is always pointing out your faults. One of the hallmarks of the critical voice is that it will call you names, like bad, fake, hopeless, loser, useless or failure. Look at the statements set out in Box 8.1: if most of them apply to you, this indicates that the self-critical voice is a strong influence in your head and in your life.

The reasons why people can tend to be self-critical vary. It may have originated with the way your parents related to you, if they tended not to reward and reinforce good conduct when you were a child, but were quick to punish you for misbehavior. Alternatively, your discipline as a child may have been unpredictable and inconsistent; in such situations children can learn to blame themselves for anything that goes wrong, as this seems like the most consistent explanation. They then carry this habit with them into adulthood. Whatever the origin of the tendency, many people continue to be self-critical as adults because they believe that it is the only way to motivate themselves to do things and to do them better. In order to consider how useful self-criticism is to you, read the story in Box 8.2 and answer the associated questions.

It is highly likely that you have chosen Coach Jones for your child. Why is this? We know that when people are continually criticized, it can damage their self-esteem and decrease their motivation, leading them to stop trying in order to avoid the criticism. When we are praised, on the other hand, we tend to try harder and work better. Thus most people would agree that Coach Jones would be more likely to get a better performance out of a child.

It is likely that for most of your life the way you have talked to yourself sounds more like Coach Smith – that you have called yourself names and criticized yourself for making mistakes, ignoring the times when you have done well. Just like the child in the story in the box, learning how you can strive to achieve without criticizing yourself will ultimately lead to a better performance. It is not about lowering your standards, but about deciding which coach you want to have for yourself – Coach Smith, the critical voice who will berate you and ignore your achievements, thus leading to a self-defeating cycle where your motivation and performance are impaired; or Coach Jones, the compassionate voice, who will recognize when you are trying and encourage you to learn from your mistakes, thus improving your performance over time.

When trying to change your self-critical voice and decrease self-criticism in your life, the ultimate goal is not to stop yourself from ever being self-critical again. This is not realistic, given that you have probably had a lifetime of listening to the self-critical voice. Also, it is important to realize that all people have a critical voice; it’s just that most of the time many of them don’t choose to listen to it or don’t choose to take its messages to heart. Setting yourself the goal of not having a critical voice will just give you one more thing to criticize yourself about the first time you encounter the critical voice! Therefore the goal is to decrease the power of the self-critical voice. Imagine the volume control on a radio that can be turned down but not off – the aim is to turn down the volume of the self-critical voice. At the same time, we want to increase the power of the compassionate voice – in other words, turn up the volume of the compassionate voice. The next section leads you through a three-step procedure for working towards these goals.

Go back to Section 7.1 on ‘identifying problem areas’ and look through your completed Worksheet 7.1.2. In the column called ‘Perfectionism thoughts’, see if you can identify those thoughts that express criticism of you. One way to help you identify these is to look for the thoughts that you would hesitate to say to another person, because they sound judgmental and critical. When you have been used to being self-critical, it can sometimes be hard to recognize the self-critical voice because you accept it as ‘truth’ or how things really are. Therefore it can be helpful to note the terms or names you call yourself that appear most frequently, as this will alert you to the self-critical voice more quickly when it speaks up in the future.

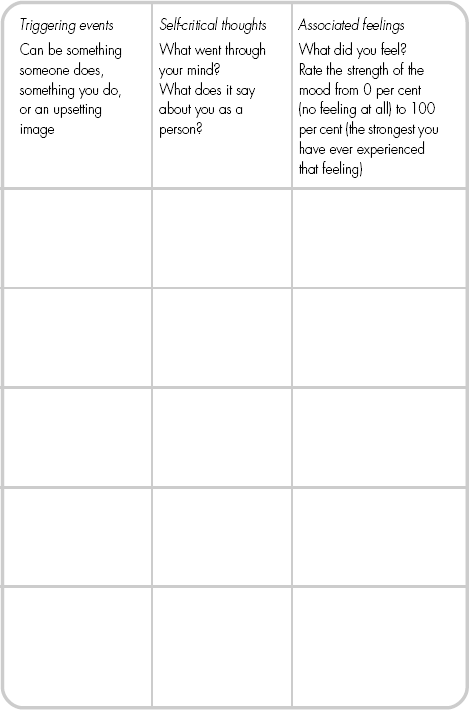

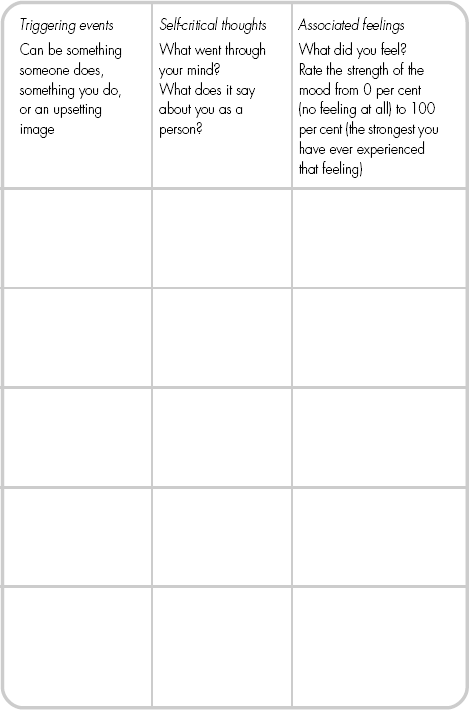

Now, for the next week, keep a diary or monitoring sheet that relates specifically to these self-critical thoughts, using Worksheet 8.1. The first column, headed ‘Triggering events’, is where you put whatever immediately preceded the self-critical thought. It may be a strong feeling that you experience that first alerts you to the fact that you are having a self-critical thought. Reflect on what may have been happening to trigger the feeling. The second column, headed ‘Self-critical thoughts’, is where you write the self-critical thought that you have in your mind. In particular, note when you over-generalize from your perceived lack of performance, or the times when you do not stick to the rules that you have imposed on yourself for achieving a certain goal, to an unfavorable judgment on yourself as a person. To help you with this, an example from Gemma’s case is provided below.

Gemma: An unfavorable judgment of herself as a person

Gemma, a university student aged 28, noticed that she felt most upset when she listened to other students answering questions in tutorials. She felt that she was incapable of sounding intellectual, confident or verbally polished. She avoided answering questions because she thought: ‘I am stupid because I can’t sound that knowledgeable in my answers.’

The third column, headed ‘Associated feelings’, asks you to describe how you felt (e.g. sad, ashamed, angry, depressed) and to rate the strength of that feeling from 0 per cent to 100 per cent. Your feelings can give you a clue as to whether self-criticism is productive or not. If you are feeling ashamed or depressed, it is unlikely that determination to achieve will follow. Rather, it is likely that you will feel less motivated to try again.

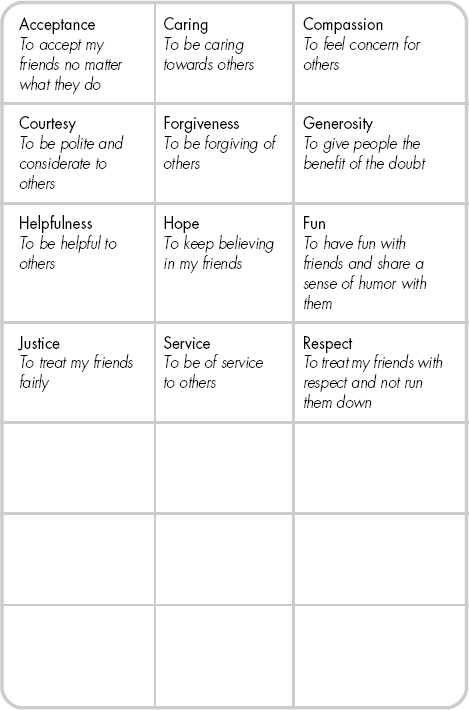

When people have been listening to the critical voice for a long time, they can find it very hard to identify their own compassionate voice. One way to help you tune in to your compassionate voice is to think about the values you apply to your friends and the people you care about in your relationships with them. Look at Worksheet 8.2 and circle those values that are of importance to you with respect to the way you treat your friends, and add any others you can think of in the empty boxes.

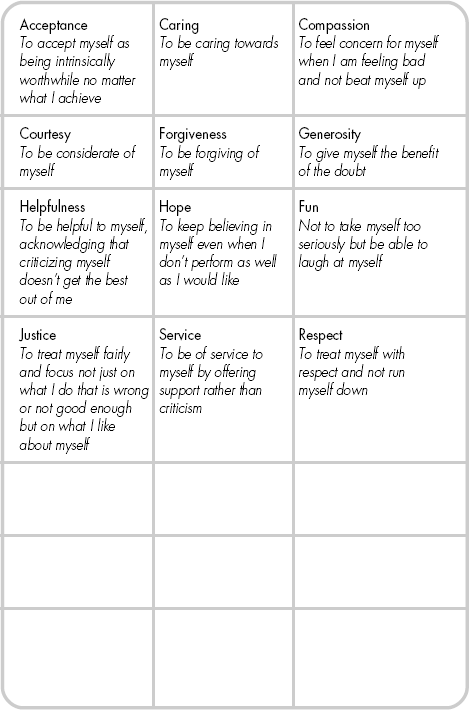

Now think about whether you apply any of those values to yourself or whether you do not. Think how different your life would look if you applied the same values to yourself. Worksheet 8.3 on page 229 shows some suggestions about how you might apply the same values you use with friends to yourself. Add in your own ideas and values in the blank boxes.

Now for another month use a new monitoring diary, as shown in Worksheet 8.4, with an example. The first three columns are the same as Worksheet 8.1, but two columns have been added. In the column headed ‘What does the compassionate voice say?’ use your knowledge of the values you apply to friends to write a specific message from the compassionate voice, which will sound like something you would say to a friend. Alternatively, returning to our coach story at the beginning of this chapter, think what you would want to say if you were talking to a child of yours. Rate your belief in that thought. At this stage your belief may be low, and much lower than your belief in your self-critical thought, but that is fine. Like any muscle group in your body, the compassionate voice will only get stronger the more it is used, and the self-critical voice will get weaker the less it is used. This takes time and practice. Imagine you were preparing to go for a cycling trip in your holidays – if you haven’t been doing any cycling for quite a while, you don’t expect to just start cycling on your holiday. Rather, you would practice beforehand, and start cycling near where you live in order to build up the muscles required to stay in the saddle for a few hours and keep pushing the pedals. After practicing over time, it feels easier to go further and faster. It is the same with the compassionate voice. As it gets exercised more, it will become stronger and more believable, and the unfairness of the self-critical voice will become more apparent. Thus you will be more likely to question the validity of the self-critical thought, and believe it less.

In the final column you will see that you are asked to rate the strength of the associated feeling once more after having identified the compassionate voice. Once again, initially this may not make a major change in your feelings, but any reduction of negative feelings will free you to achieve more and paralyze yourself less with criticism.

Imagine your self-critical voice is like a bully. We know that there are a couple of ways to respond to bullying that can be helpful. The first is to have a practiced response ready to use when the bullying occurs, so that you don’t react spontaneously and therefore show that the bully is getting to you. The second is to observe but not react to the bullying. We will examine in turn how each of these strategies might help you in combating your critical voice.

When the self-critical voice is dominating, it is difficult to remember or hear the compassionate voice. Therefore it can be very helpful to have the compassionate voice written down, in order to make it much more salient and audible. In order to have a practiced and helpful response to use when your critical voice is loud, you will need to identify the types of compassionate thoughts that most helped your mood and motivation in the diary (Worksheet 8.4) that you were keeping. Write out the most helpful thoughts on small index cards, or even pieces of paper the size of a business card. There should be just one thought per card. You can carry these around with you in your purse or wallet so that they are readily available no matter where you are. You can also put them up around the house, on a wall or fridge, if you do not mind other people seeing them. Over the page are some examples of the compassionate voice that may be helpful ways to respond to the self-critical voice. It may also be helpful to say the words on the cards out loud at times (when no one else is around) as this may help the compassionate voice get a firmer hold in your mind.

The self-critical voice is always going to look for the worst – that doesn’t make it true or a fair reflection of my efforts and abilities.

When I don’t achieve the standards I set myself, it doesn’t make me any less worthwhile as a person.

I don’t judge others based on what they achieve and so I will refuse to judge myself based on what I achieve.

Having and pursuing high standards is fine. Judging myself as being faulty as a person based on reaching these standards will only get in the way of my attaining these standards.

Making mistakes is part of the learning process and the pathway to attaining excellence.

The second way of responding to the self-critical voice is to observe but not to react to it. This is a technique called acceptance, which is about experiencing without judging. Acceptance has been found to reduce negative mood states. For example, it decreases depressive episodes in people who experience recurrent depression, and it has also been found to decrease body dissatisfaction.

In some ways, using acceptance to respond to the critical voice is like keeping the first thought diary from this chapter (Worksheet 8.1) in your head. When practicing this technique, you are encouraged simply to observe the self-critical thoughts and feelings that follow when you hear the self-critical voice by bringing them to your awareness and holding them there. One way to relate to unpleasant experiences is to register that they are there, to allow them to be as they are in that moment and simply hold them in awareness.

When practicing this technique it is often helpful to close your eyes, if that feels comfortable for you. The first step is being aware, really aware, of what is going on with you right now. Think of thoughts as if they were projected on the screen at the cinema. You sit, watching the screen, waiting for the thought or image to arise. When it does, you pay attention to it so long as it is there ‘on the screen’ and then let it go as it passes away. The second step is just to acknowledge the thoughts rather than try to push them away or shut them out, perhaps saying, ‘Ah, there you are, that’s how it is right now.’ Similarly with sensations in the body: if there are sensations of tension, of holding, or whatever, then encourage awareness of them, simply noting them: ‘OK, that is how it is right now.’ It can be helpful to label what the thoughts or sensations are, without having to react to them. For example, you might say to yourself, ‘A self-critical thought has just come into my mind’ without having to engage with the thought, or ‘A feeling of anxiety has just come in’ without having to engage with the feeling.

You can also think of your thoughts like an old tape or re-run of a film, so that you might say to yourself, ‘This is my self-criticism tape again.’ This helps us to recognize the repetitive nature of our self-critical thoughts, without necessarily having to engage with them or listen to them. It is a bit like listening to a radio station. When the self-critical thoughts come on the radio, do you have to choose to turn up the volume and listen to them and give them airplay? Or could you choose to leave the volume on the radio where it is and just wait for the next track to come in, without having to give particular attention to listening in to the self-critical thoughts?

As you practice these techniques over time, we expect that the compassionate voice will get stronger and the self-critical voice weaker. As we pointed out earlier in this chapter, though, this does not mean that the self-critical voice will disappear. Also, you can expect progress to be uneven: on some days it will be easier to listen to the compassionate voice than on others. You can also expect that over time there will be periods in your life when the self-critical voice starts to become louder again and tries harder to capture your attention. Usually this will indicate that some trigger has occurred in your life that has caused you to feel bad about yourself so that you start listening to the self-critical voice again. It can be helpful to identify the trigger, and to use the problem-solving tool to deal with this, as outlined in Section 7.8 of this book. If there is nothing that can be done about the trigger, you will still benefit from practicing the techniques in this chapter, reintroducing them fully into your life. You can expect them to be effective more quickly, as you have already laid down a foundation on which they can be rebuilt. Above all, don’t be disappointed in yourself when the self-critical voice gets louder. This is part of the natural ebb and flow of thoughts in our lives, and each time you experience difficulties and work your way through them, you are consolidating your learning and getting a little further ahead.