This Step begins with an overview of the effects of AN and dieting on metabolism. People with AN often believe in many myths about changes in weight and what will happen to them if they eat normally; for example, you may have a powerful fear that you will gain weight in a completely uncontrolled way if you relax your strict controls in the tiniest degree.

Having set out the information relating to the possible barriers that may prevent you from making changes to your diet – in particular, how and why normal fluctuations occur in an individual’s weight, and the ways in which the body responds to starvation and to a resumption of normal eating – a system of food portions is introduced by which you can begin to regulate your food intake in a manner which is controlled but not rigid.

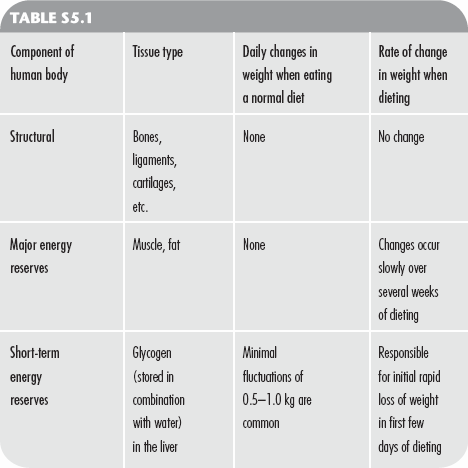

In studies that have investigated the normal changes in body weight in healthy, free-living individuals, a fluctuation of 1kg (2.2lb) between consecutive days is common, and fluctuations of 0.5 kg (1.1lb) very common. In order to understand the reasons for these variations in body weight during short periods, it is worth considering the various components of the human body which can change in size and thus result in change in weight. These are set out in Table S5.1.

Although loss of mineral from the bones is a common side-effect of starvation, the effects of this on body weight are small. The body’s glycogen stores are specifically designed to provide energy in the short term, i.e. between meals, and in normal circumstances they last only for a few hours. Only when glycogen stores are almost exhausted does the body start to break down muscle and fat stores to release energy.

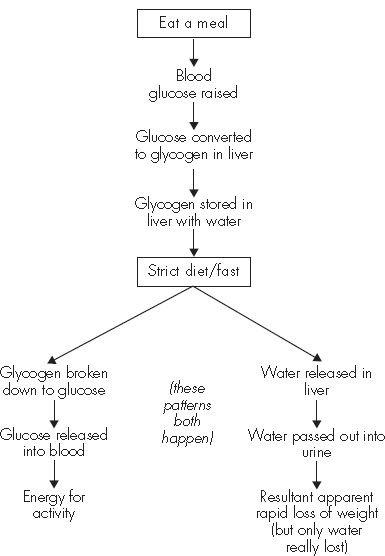

Figure S5.1 Effects of eating and not eating on energy stores and body weight

Figure S5.1 shows what happens when someone does not eat or goes on a very restricted diet. When that person starts to eat or to increase their intake, the diagram will flow in the opposite direction. That is, the excess glucose in the blood will be taken up into the liver in combination with water and stored as glycogen. This may occur either following a binge or when someone increases their diet in a more planned way. In either situation, if weight is checked a rapid increase will be observed, which frequently leads to further dietary restriction in order to reverse the weight gain.

If you look again at the bottom left-hand side of Figure S5.1, you see that burning glycogen gives you energy but no weight loss. The weight loss comes on the right-hand side, but in fact all that is lost is water; and so, as soon as you start to eat again the weight is rapidly regained, even though you have not taken in many calories.

There are two important messages from this analysis for people with eating disorders contemplating dietary changes:

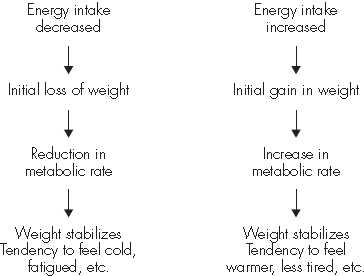

During the millions of years over which the human body has evolved it has developed a number of mechanisms to attempt to protect it from adverse environmental circumstances – for example, temperature regulation, responses to lack of oxygen at altitude, etc. Among these adverse environmental circumstances is lack of food, and to protect itself in times of shortage or famine the body lowers the metabolic rate, enabling itself to survive on less food. This process reinforces the fear of weight gain in people who have rigorously dieted.

Figure S5.2 shows the changes in the metabolic rate and subsequently in body weight which occur with changes in energy intake. It can be seen that, when a body is starved and then there is an increase in dietary intake, there will be a weight gain in the short term at a greater rate than for a non-starved person. This short-term gain can be a difficult time, but after a spell of higher intake the metabolic rate and therefore energy requirements are increased. There is no evidence of permanently lowered energy requirements in people who increase their intake following starvation. In other words, your body’s energy thermostat always resets itself.

Figure S5.2 Changes in metabolic rate

These processes of decreasing and increasing metabolic rates apply not just to periods of starvation resulting in weight loss, but also to those who starve, binge and vomit at a stable weight. The reduction in metabolic rate is reversed when regular eating patterns are re-established, particularly if food intake is distributed throughout the day.

This section sets out a techniques for regaining control of your eating by applying a ‘portion’ system. The potential benefits of this system for the person attempting to overcome AN are:

A system of food ‘portions’ is used to vary the overall level of food intake. These ‘portions’ are applied primarily to what are usually termed carbohydrate foods, including bread, potatoes, fruit, crackers and biscuits, rice, cereals, pasta, cakes and puddings. Protein foods, such as meat, fish, eggs, cheese and beans, are taken in relatively fixed amounts and are not included in the ‘portion’ total. Vegetables and drinks such as tea and coffee can be taken as you wish, but avoid taking them instead of carbohydrate ‘portions’. Milk (or a suitable alternative, such as soya milk) should be used in tea and coffee and with cereals.

The foods to which the portion system is applied are of variable calorie content, but so long as a variety of foods is chosen each day a constant intake will result.

The following amounts of typical foods each count as one portion:

The following amounts of other foods count as two portions:

To start with, you should try to aim to eat 15 ‘portions’ per day, preferably spread across breakfast, midday meal, evening meal and snacks. It is important to spread the intake of food through the day to avoid feelings of over-fullness, which may make the planned intake difficult to achieve if you try to eat too much at once. You should aim to include a helping of protein-rich food – meat, fish, eggs, cheese or beans – with your midday and evening meals (for example, in a sandwich at midday and as part of the main course in the evening).

Once you have established a regular pattern of meals, adjustments can be made to the total number of ‘portions’ in order to bring about controlled changes in your weight. These adjustments are best made infrequently, i.e. no more than one change every two weeks or so.