5

ECONOMIC GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

China’s economic development has been miraculous, with an average annual GDP growth rate of 9.9 percent and trade growth rate of 16.3 percent, since the transition from a planned economy to a market economy in 1979. This chapter attempts to provide answers to five related questions: why was it possible for China to achieve such extraordinary growth performance during its transition? Why was China unable to attain similar success before its transition started? Why did most other transition economies, both socialist and nonsocialist, fail to achieve a similar performance? What costs does China pay for its extraordinary success? Can China maintain dynamic growth in the coming decades? The chapter argues that China’s extraordinary development performance in the transition was a result of developing its economy according to its comparative advantages which allowed China to tap into the “latecomer advantage.” The poor performance before the transition was due to China’s attempt to develop comparative advantage-defying capital-intensive heavy industries while China was a capital-scarce agrarian economy. Other transition economies failed to achieve a similar performance because they adopted a shock therapy causing the collapse of their economies; whereas China adopted a gradual dual-track approach, which achieves stability and dynamic growth simultaneously. The costs of this transition approach are widening income disparities and other social economic issues – China, however, has the potential to maintain dynamic growth in the coming decades if the remaining distortions as a legacy of dual-track transition are eliminated.

China was one of the most advanced and powerful countries in the world for more than a thousand years before the modern era. Even in the nineteenth century it dominated the world economic landscape. According to Angus Maddison, the famous economic historian, China accounted for a third of global GDP in purchasing power parity in 1820 (Figure 5.1). But with the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth century, the West quickly rose, and China slid. And, with a weaker economy, it was defeated repeatedly by the Western powers, becoming a quasi-colony, ceding extraterritorial rights in treaty ports to twenty foreign countries. Its customs revenues were controlled by foreigners, and it surrendered territory to Britain, Japan, and Russia.

Since China’s defeat in the Opium War in 1840, the country’s elites, like those in other parts of the developing world, strived to make their motherland a powerful and respected nation again. But their efforts produced little success. China’s share of global GDP shrank to about 5 percent and stayed low until 1979 (Figure 5.1).

China’s economic fate then changed dramatically at the end of the 1970s when it started to implement the reform and opening strategy. Since then, its economic performance has been miraculous. Between 1979 and 1990, China’s average annual growth rate was 9.0 percent.1 At the end of that period and even up to the early 2000s, many scholars still believed that China could not continue that growth rate much longer due to the lack of fundamental reforms.2 But China’s annual growth rate during the period 1991–2011 increased to 10.4 percent. On the global economic scene, China’s growth over the last three decades has been unprecedented. This was a dramatic contrast with the depressing performance of other transitional economies in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.

As a result of the extraordinary performance, there has been a dramatic change in China’s status in the global economy. In 1979, China barely registered on the global economic scale, commanding a mere 0.98 percent of global GDP in current US dollars. Today, it is the world’s second largest economy and produces 8.4 percent of global GDP (in 2011).

In 1979, China was a low-income country; its income per capita of US$82, as at the current US dollar value, was less than one-third of the average in sub-Saharan countries. It is now an upper middle-income country. In 2011 its income per capita reached US$5,444 over three times the level of sub-Saharan Africa. As a result of this extraordinary performance, more than 600 million people have got out of poverty in China.

At the start of this transition, China was also an inward-oriented economy with a trade dependence (trade-to-GDP) ratio of 17.9 percent, less than one half of the world average. China’s average annual trade growth rate measured in current US dollars between 1979 and 2011 was an astonishing 16.3 percent. Now China is the largest exporter of goods in the world. Its imports and exports contributed to 8.4 percent of the global trade in 2011.

Behind this growth and trade expansion, there has been a dramatic structural transformation – in particular, rapid urbanization and industrialization. At the start of economic reforms in 1979, China was primarily an agrarian economy; 81 percent of its population lived in rural areas, and primary products comprised 31.3 percent of GDP. The shares declined to 48.7 percent and 10.1 percent respectively in 2011. A similar change also occurred in the composition of China’s exports. In 1980 primary products comprised 50.3 percent of merchandise exports. Now, 80.6 percent of China’s exports are manufactures.

Accompanying the change in the composition of China’s exports is the accumulation of foreign reserves. Even up to 1990, China’s foreign reserves were US$11.1 billion, barely enough to cover 2.5 months of imports, and its reserves today are over US$3 trillion – the largest in the world.

China’s dynamic growth made significant contributions to the world as well. China withstood the shocks and maintained dynamic growth in the East Asian financial crisis in 1998 and the global crisis in 2008. China’s decision to maintain the renminbi’s stability helped other East Asian economies avoid a competitive devaluation, which contributed tremendously to quick recovery of the crisis-affected countries. China’s dynamic growth in the current global crisis was a driving force for the global recovery.

The spectacular performance over the past three decades far exceeded the expectations of anyone at the outset of the transition, including Deng Xiaoping, the architect of China’s reform and opening-up strategy.3

Can China maintain dynamic growth in the coming decades? The chapter will conclude with a few lessons from the experiences of China’s development for other countries.

Rapid, sustained increase in per capita income is a modern phenomenon. Studies by economic historians, such as Angus Maddison (2001), show that average annual per capita income growth in the West was only 0.05 percent before the eighteenth century, jumping to about 1 percent in the nineteenth century and reaching about 2 percent in the twentieth century. That means that per capita income in Europe took 1,400 years to double before the eighteenth century, about 70 years in the nineteenth century, and 35 years thereafter.

A continuous stream of technological innovation and industrial upgrading is the basis for sustained growth in any economy in any time (Lin 2012b). The dramatic surge in growth in modern times in the West is a result of a paradigm shift in technological innovation. Before the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth century, technological innovations were generated mostly by the experiences of craftsmen and farmers in their daily production. After the Industrial Revolution, experience-based innovation was increasingly replaced by field experimentation and, later, by science-based experiments conducted in scientific laboratories (Lin 1995; Landes 1998). This shift accelerated the rate of technological innovation, marking the coming of modern economic growth and contributing to the dramatic acceleration of income growth in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Kuznets 1966).

The Industrial Revolution not only accelerated the rate of technological innovation but also transformed industrial, economic, and social structures. Before the eighteenth century every economy was agrarian; 85 percent or more of the labor force worked in agriculture, mostly in self-sufficient production for the family. The acceleration of growth was accompanied by a move of labor from agriculture to manufacturing and services. The manufacturing sector gradually moved from very labor-intensive industries at the beginning to more capital-intensive heavy and high-tech industries. Finally, the service sector came to dominate the economy. Accompanying the change in industrial structure was an increase in the scale of production, the required capital and skill, the market scope, and the risks. To exploit the potential unleashed by new technology and industry, and to reduce the transaction costs and share risks requires innovations as well as improvements in an economy’s hard infrastructure, such as power and road networks, and its soft infrastructure. Soft infrastructure consists of such elements as belief, the legal framework, financial institutions, and the education system (Lewis 1954; Kuznets 1966; North 1981; Lin 2011).

A developing country such as China, which started its modernization drive in 1949, potentially has the advantage of backwardness in its pursuit of technological innovation and structural transformation (Gerschenkron 1962; World Bank 2008). In advanced high-income countries technological innovation and industrial upgrading require costly and risky investments in research and development, because their technologies and industries are located on the global frontier. Moreover, the institutional innovation, which is required for realizing the potential of new technology and industry, often proceeds in a costly trial-and-error, path-dependent, evolutionary process (Fei and Ranis 1997). By contrast, a latecomer country in the catching-up process can borrow technology, industry, and institutions from the advanced countries at low risk and costs. So if a developing country knows how to tap the advantage of backwardness in technology, industry, and social and economic institutions, it can grow at an annual rate several times that of high-income countries for decades before closing its income gap with those countries.

In the post-World War II period, 13 of the world’s economies achieved average annual growth of 7 percent or above for 25 years or more. The Commission on Growth and Development, headed by Nobel Laureate Michael Spence, finds that the first of five common features of these thirteen economies is their ability to tap the potential of the advantage of backwardness. In the commission’s language, the 13 economies: “imported what the rest of the world knew and exported what it wanted” (World Bank 2008: 22).4

After the transition was initiated by Deng Xiaoping in 1979, China became one of those 13 successful economies by adopting an opening-up strategy and starting to tap this potential (of importing what the rest of the world knows and exporting what the world wants). This is demonstrated by the large inflows of foreign direct investment and the rapid growth in its international trade, the dramatic increase in its trade dependence ratio. While in 1979 primary and processed primary goods accounted for more than 75 percent of China’s exports, the share of manufactured goods had increased to 95 percent by 2010. Moreover, China’s manufactured exports upgraded from simple toys, textiles, and other cheap products in the 1980s and 1990s to high-value and technologically sophisticated machinery and information and communication technology products in the 2000s. The exploitation of the advantage of backwardness has allowed China to emerge as the world’s workshop and to achieve extraordinary economic growth by reducing the costs of innovation, industrial upgrading, and social and economic transformation (Lin 2012a).

China possessed the advantage of backwardness long before the transition began in 1979. The socialist government won the revolution in 1949 and started modernizing in earnest in 1953. Why had China failed to tap the potential of the advantage of backwardness and achieve dynamic growth before 1979? This failure came about because China adopted a wrong development strategy at that time.

China was the largest economy and among the most advanced, powerful countries in the world before pre-modern times (Maddison 2007). Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and other first-generation revolutionary leaders in China, like many other Chinese social and political elites, were inspired by the dream of achieving rapid modernization.

The lack of industrialization – especially the lack of large heavy industries that were the basis of military strength and economic power – was perceived as the root cause of the country’s backwardness. Thus it was natural for the social and political elites in China to start nation building by prioritizing the development of large, heavy, advanced industries after the Revolution.5 In the nineteenth century the political leaders of France, Germany, the United States, and other Western countries pursued effectively the same strategy, motivated by the contrast between Britain’s rising industrial power and the backwardness of their own industry (Gerschenkron 1962; Chang 2003).

Starting in 1953, China adopted a series of ambitious Five-Year Plans to accelerate the building of modern advanced industries with the goal of overtaking Britain in ten years and catching up to the United States in fifteen. But China was a low-income agrarian economy at that time. In 1953, 83.5 percent of its labor force was employed in the primary sector, and its per capita income (measured in purchasing power parity terms) was only 4.8 percent of that of the United States (Maddison 2001). Given China’s employment structure and income level, the country did not possess a comparative advantage in the modern advanced capital-intensive industries of high-income countries; furthermore, Chinese firms in those industries were not viable in an open competitive market.6

To achieve its strategic goal, the Chinese government needed to protect the priority industries by giving firms in those industries a monopoly and subsidizing them through various price distortions, including suppressed interest rates, an overvalued exchange rate, and lower prices for inputs. The price distortions created shortages, and the government was obliged to use administrative measures to mobilize and allocate resources directly to nonviable firms (Lin 2009; Lin and Li 2009).

These interventions enabled China to quickly establish modern advanced industries, test nuclear bombs in the 1960s, and launch satellites in the 1970s. But the resources were misallo-cated, the incentives were distorted, and the development of labor-intensive sectors in which China had a comparative advantage was repressed. As a result, economic efficiency was low, and the growth before 1979 was driven mainly by an increase in inputs.7 Despite a very respectable average annual GDP growth rate of 6.1 percent in 1952–1978 and the possession of a wide range of large modern industries, China was still a poor agrarian economy in terms of employment structure before the transition started in 1979, with 71.3 percent of its labor force in traditional agriculture. In 1952–1978 household consumption grew by only 2.3 percent a year, in sharp contrast to the 7.1 percent average growth after 1979.

All other socialist countries and many developing countries after World War II adopted a development strategy similar to that of China. Most colonies gained political independence after the 1950s. Compared with developed countries, these newly independent developing countries had extremely low per capita income, high birth and death rates, low average educational attainment, and very little infrastructure – and were heavily specialized in the production and export of primary commodities while importing most manufactured goods. The development of modern advanced industries was perceived as the only way to achieve rapid economic takeoff, avoid dependence on the Western industrial powers, and eliminate poverty (Prebisch 1950).

It became a fad after the 1950s for developing countries in both the socialist and the non-socialist camps to adopt an import substitution strategy to accelerate the development of capital-intensive modern advanced industry in their countries (Lal and Mynt 1996; Lin 2012c). But the capital-intensive modern industries on their priority lists defied the comparative advantages determined by the endowment structure of their low-income agrarian economies. To implement their development strategy, both socialist and nonsocialist developing countries introduced distortions and government interventions similar to those in China.8 This strategy made it possible to establish some modern industries and achieve investment-led growth for one or two decades in the 1950s to the 1970s. Nevertheless, the distortions led to pervasive soft budget constraints, rent-seeking, and misallocation of resources (Lin and Tan 1999). Economic efficiency was unavoidably low. Stagnation and frequent social and economic crises began to beset most socialist and nonsocialist developing countries by the 1970s and 1980s. Liberalization from excessive state intervention became a trend in the 1980s and 1990s.

The symptoms of poor economic performance and social and economic crises, and their root cause in distortions and government interventions, were common to China and other socialist transition economies as well as other developing countries. But the academic and policy communities in the 1980s did not realize that those distortions were second-best institutional arrangements, endogenous to the needs of protecting nonviable firms in the priority sectors. As a result, they recommended that socialist and other developing countries immediately remove all distortions by implementing simultaneous programs of liberalization, privatization, and marketization with the aim of quickly achieving efficient, first-best outcomes (Lin 2009).

But if those distortions were eliminated immediately, many nonviable firms in the priority sectors would collapse, causing a contraction of GDP, a surge in unemployment, and acute social disorders. To avoid those dreadful consequences, many governments continued to subsidize the nonviable firms through other, disguised, less efficient subsidies and protections (Lin and Tan 1999). Transition and developing countries thus had even poorer growth performance and stability in the 1980s and 1990s than in the 1960s and 1970s (Easterly 2001).

During the transition process China adopted a pragmatic, gradual, dual-track approach. The government first improved the incentives and productivity by allowing the workers in the collective farms and state-owned firms to be residual claimants and to set the prices for selling at the market after delivering the quota obligations to the state at fixed prices (Lin 1992, 2012a). At the same time, the government continued to provide necessary protections to nonviable firms in the priority sectors and simultaneously, liberalized the entry of private enterprises, joint ventures, and foreign direct investment in labor-intensive sectors in which China had a comparative advantage but that were repressed before the transition. This transition strategy allowed China both to maintain stability by avoiding the collapse of old priority industries and to achieve dynamic growth by simultaneously pursuing its comparative advantage and tapping the advantage of backwardness in the industrial upgrading process. In addition, the dynamic growth in the newly liberalized sectors created the conditions for reforming the old priority sectors. Through this gradual, dual-track approach China achieved “reform without losers” (Naughton 1995; Lau et al. 2000; Lin et al. 2003) and moved gradually but steadily to a well-functioning market economy.

A few other socialist economies – such as Poland,9 Slovenia, and Vietnam, which achieved outstanding performance during their transitions – adopted a similar gradual, dual-track approach (Lin 2009). Mauritius adopted a similar approach in the 1970s to reform distortions caused by the import-substitution strategy to become Africa’s success story (Subramanian and Roy 2003).10

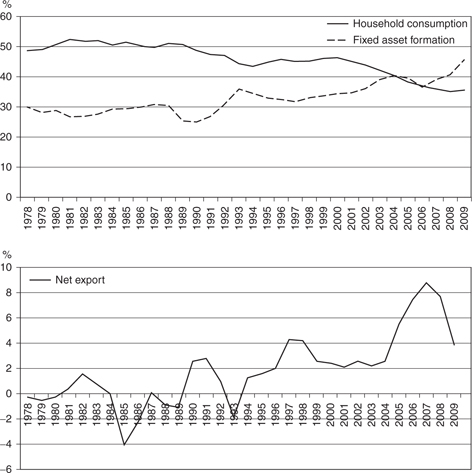

The gradual, dual-track approach to transition is a double-edged sword. While it enables China to achieve enviable stability and growth in the transition process, it also brings with it a number of structural problems, particularly the disparities in income distribution, consumption and savings, and external account.11 When the transition started in 1979, China was a relatively egalitarian society. With the rapid growth, the income distribution has become increasingly unequal. The Gini coefficient, a measurement of income inequality, increased from .31 in 1981 to .47 in 2008 (Ravallion and Chen 2007). Meanwhile, household consumption as a percentage of GDP dropped from about 50 percent down to about 35 percent, whereas the fixed asset investment increased from around 30 percent to more than 45 percent of GDP (see top panel of Figure 5.2), and the net exports increased from almost nothing to a high of 8.8 percentage of GDP in 2007 (see bottom panel of Figure 5.2). As I will elaborate below, such disparities are the by-products of remaining distortions in the dual-track approach to transition, which favor the large corporations and the rich.

During the transition process, the Chinese government retained some distortions as a way to provide continuous support to nonviable firms in the previous strategy’s priority industries (see section 3). Major remaining distortions include the concentration of financial services in the four large state-owned banks and equity market, the almost zero royalty on natural resources, and the monopoly of major service industries, including telecommunication, power, and banking.12

Those distortions contribute to the stability in China’s transition process. They also contribute to the rising income disparity and other imbalances in the economy. This is because only big companies and rich people have access to credit services provided by the big banks and equity market and the interest rates are artificially repressed. As a result, big companies and rich people are receiving subsidies from the depositors who have no access to banks’ credit services and are relatively poor. The story is similar for the equity market. The concentration of profits and wealth in large companies and widening of income disparities are unavoidable. The low royalty levies of natural resources and the monopoly in the service sector have similar effects.

Figure 5.2 Contributions of household consumption, fixed asset formation, and net exports to GDP

Source: National Statistical Bureau (2010: 36)

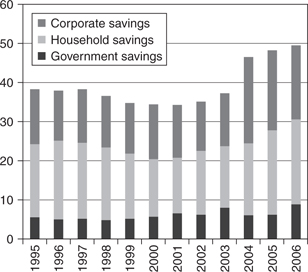

In general, the higher-income households have a lower marginal propensity to consume than the lower-income households. Therefore, if wealth is disproportionately concentrated in the higher-income group, the nation’s consumption-to-GDP ratio will be lower and saving’s ratio will be higher. The concentration of wealth in the large firms has a similar effect. A consequence of such an income distribution pattern is the relative high household savings and extraordinarily high corporate savings in China as shown in Figure 5.3.

The high household and corporate savings in turn lead to a high rate of investment and quick building up of production capacity. A large trade surplus is a natural consequence of limited domestic absorption capacity due to low consumption ratio. Therefore, it is imperative for China to address the structural imbalances, by removing the remaining distortions in the finance, natural resources, and service sectors so as to complete the transition to a well-functioning market economy. The necessary reforms include: first, removing the financial repression and allowing the development of small and local financing institutions, including local banks, so as to increase financial services, especially access to credit, to household farms as well as small- and medium-size enterprises in manufacturing and service sectors; second, reforming the pension system, removing the old retired workers’ pension burden from the state-owned mining companies and levying appropriate royalty taxes on natural resources; and, third, encouraging entry and competition in the telecommunication, power, and financial sectors.

No country other than China has maintained annual growth of 9 percent for more than three decades. Can China keep growing that fast for another two decades or even longer? The answer, based not on some optimistic estimate but on the potential advantages of backwardness, is yes. In 2008 China’s per capita income was 21 percent of that of the US, measured in purchasing power parity by Maddison’s estimates.13 The income gap between China and the US indicates that there is still a large technological gap between China and the industrialized countries. China can thus continue to enjoy the advantages of backwardness before closing the gap.

Figure 5.3 China’s corporate, household, and government savings as percentage of GDP

Source: China Statistical Yearbook (1998–2009)

Maddison’s estimates show that China’s current status relative to the US is similar to that of Japan in 1951, Singapore in 1967, Taiwan, China in 1975, and Korea in 1977. GDP grew 9.2 percent in Japan between 1951 and 1971, 8.6 percent in Singapore between 1967 and 1987, 8.3 percent in Taiwan, China between 1975 and 1995, and 7.6 percent in Korea between 1977 and 1997. China’s development strategy after the reform in 1979 is similar to that of Japan, Singapore, Korea, and Taiwan, China. Therefore, from the point of advantage of backwardness, China has the potential to achieve another 20 years of 8 percent growth.

Japan’s income per capita measured in purchasing power parity was 65.6 percent of that of the US in 1971, Singapore’s was 53.8 percent in 1987, Taiwan’s was 54.2 percent in 1995, and Korea’s was 50.2 percent in 1997. If China can realize the potential, 20 years from now, China’s per capita income measured in purchasing power parity may reach about 50 percent of the US per capita income. Measured by purchasing power parity, China’s economy may be twice as large as that of the US in 2030; measured by market exchange rates, depending on how fast China revalues its currency, Chinese economy may be at least about the same size as that of the US.

Many economic and noneconomic factors will decide whether China can realize its full potential. Along with its rapid growth, China, as a developing country in transition, has encountered problems never seen before – problems that need to be addressed.

In the very early stages of the reform and opening, the gaps between the urban and rural areas and those between the eastern, central, and western parts of the country were narrowing. But after 1985 they widened. The Gini coefficient (a measure of income equality, with a coefficient of 0 as perfect equality, and 1 as perfect inequality) increased from 0.31 in 1981 to 0.42 in 2005, approaching the level of Latin American countries (World Bank 2010). As Confucius once said: “Inequity is worse than scarcity.” Indeed, a widening income disparity would cause bitter resentment among the low-income group. In addition, the educational, medical, and public health systems are underdeveloped. So the income gap could cause tensions, undermining social harmony and stability.

China’s rapid growth has consumed massive energy and resources. In 2006, with 5.5 percent of the world’s GDP, it consumed 9 percent of the world’s oil, 23 percent of alumina, 28 percent of steel, 38 percent of coal, and 48 percent of cement. Natural resources are limited. So, if China doesn’t change its growth pattern or reduce its resource consumption, the fallout will inflict harm on other countries for generations to come. In addition, rising resource prices will increase the cost of overconsumption, which runs counter to the scientific development strategy promoted by the Communist Party.

The environmental problems caused by breakneck development are also serious. The mining disasters and natural calamities in recent years are testimony to environmental deterioration.

Natural disasters can deliver fatal blows, so protecting the environment to prevent disasters is important in China as well.

China has had both current account surpluses and capital account surpluses since 1994. Before 2005 the current account surplus was relatively small, but it reached 7.6 percent of GDP in 2007. As a result of the large trade surplus, China accumulated foreign reserves rapidly, with more than US$3 trillion – the largest in the world.

Accompanying the rising trade surpluses was the rising trade deficit in the United States. The imbalances received much attention before the current global financial crisis in 2008. In a testimony before the United States Congress, C. Fred Bergsten of the Peterson Institute stated in 2007: “The global imbalances probably represent the single largest current threat to the continued growth and stability of the United States and world economies” (Bergsten 2007). Throughout the crisis, there have been claims that the most severe global recession since the Great Depression was caused in part or wholly, by global imbalances, especially the imbalances between the United States and China. Some economists, such as Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman, argued that the undervaluation of the renminbi caused the large US trade deficit and that the consequent Chinese purchases of US Treasury bonds lowered interest rates and caused the US equity and real estate bubbles, leading to the financial crisis (Krugman 2009, 2010). Others argued that a revaluation of the renminbi to rebalance US and China trade was a prerequisite for a sustained global recovery (Goldstein 2010).

Before the reform, when people from different social circles had but a single income source, corruption was visible and easy to prevent. But in the post-reform era, when material incentives became major tools to enhance efficiency, income sources became more diversified, and various gray and dark incomes harder to spot. Widespread official corruption has further widened the income gap, increasing resentment among the groups whose interests have been undermined and impairing the credibility of the government. Once that happens, it’s hard to maintain social cohesion in a major crisis, and economic and social stability can be undermined.

China’s education policies focus more on quantity than quality, which is detrimental to training workers and to long-term social progress. No matter what form technological innovation takes, borrowing from abroad or conducting domestic R&D, China has to rely on talent, and without good education, innovation is impossible.

The above hurdles are not the only ones. Others include underdeveloped social security systems, low levels of technology, rampant local protectionism, mounting challenges from globalization, inadequate legal systems, and many other political, economic, social, and even external problems, each of which needs to be identified and addressed. If they cannot be addressed promptly, any one of them could produce social and economic havoc, even political instability. Without a stable political and economic climate, China will not achieve its goal of rapid growth and fulfill its economic potential. To realize the potential, China needs to remove the remaining distortions as legacies of the dual-track approach to reform, complete the transition to a

well-functioning market economy, and overcome other social, political, and geopolitical hurdles in its modernization process.

Are there useful lessons that can be drawn from China’s development experiences over the past six decades? The answer is clearly yes. Every developing country has the opportunity to accelerate its growth if it knows how to develop its industries according to its comparative advantage at each level of development and to tap the advantage of backwardness in its technological innovation and structural transformation. A well-functioning market is a precondition for developing an economy’s industries according to its comparative advantages, because only with such a market can relative prices reflect the relative scarcities of factors of production in the economy. Such a well-functioning market naturally propels firms to enter industries consistent with the country’s comparative advantages. If a developing country follows its comparative advantage in technological and industrial development, it will be competitive in domestic and international markets. In other words, it will grow fast, accumulate capital rapidly, and upgrade its endowment structure quickly. When the endowment structure is upgraded, the economy’s comparative advantage changes and its industrial structure as well as hard and soft infrastructure need to be upgraded accordingly. In the process it is desirable for the state to play a proactive, facilitating role in compensating for externalities created by pioneer firms in the industrial upgrading and coordinating the desirable investments and improvements in soft and hard infrastructure, for which individual firms cannot internalize in their decisions. Through the appropriate functions of competitive markets and a proactive, facilitating state, a developing country can tap the potential of the advantage of backwardness and achieve dynamic growth (Lin 2011).

Many developing countries, as a result of their governments’ previous development strategies, have various kinds of distortions and many existing firms are nonviable in an open competitive market. In this respect, China’s experience in the transition process in the past 30 years also provides useful lessons. In the reform process it is desirable for a developing country to remove various distortions of incentives to improve productivity and at the same time adopt a dual-track approach, providing some transitory protections to nonviable firms to maintain stability but liberalizing entry into sectors in which the country has comparative advantages so as to improve the resource allocation and to tap the advantage of backwardness. If they can do this, other developing countries can also achieve stability and dynamic growth in their economic liberalization process.

Thirty years ago no one would have imagined that China would be among the 13 economies that tapped the potential of the advantage of backwardness and realized average annual growth of 7 percent or above for 25 or more years. For developing countries now fighting to eradicate poverty and close the gap with high-income countries, the lessons from China’s transition and development will help them join the list of those realizing growth of 7 percent or more for 25 or more years in the coming decades.

1. Unless indicated otherwise, statistics on the Chinese economy reported in this chapter are taken from World Bank (2012), National Statistical Bureau (2009, 2012), and various editions of the China Statistical Yearbook.

2. The Coming Collapse of China by Gordon H. Chang, published in 2001 by Random House, was one representation of such views.

3. Deng’s goal at that time was to quadruple the size of China’s economy in 20 years, which would have meant an average annual growth of 7 .2 percent. Most people in the 1980s, and even as late as the early 1990s, thought that achieving that goal was an impossible mission.

4. The remaining features are, respectively, macroeconomic stability, high rates of saving and investment, market system, and committed, credible, and capable governments. Lin and Monga (2010) show that the first three features are the result of following the economy’s comparative advantages in developing industries at each stage of its development, and the last two features are the preconditions for the economy to follow its comparative advantages in developing industries.

5. The desire to develop heavy industries existed before the socialist elites obtained political power. Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the father of modern China, proposed the development of “key and basic industries” as a priority in his plan for China’s industrialization in 1919 (Sun 1929).

6. While the policy goals of France, Germany, and the United States in the late nineteenth century were similar to that of China in the mid-1950s, the per capita incomes of the three countries were about 60–75 percent of Britain’s at the time. The small gap in per capita incomes indicated that the industries on the governments’ priority lists were the latent comparative advantages of the three countries (Lin and Monga 2011).

7. Estimates by Perkins and Rawski (2008) suggest that the average annual growth of total factor productivity was 0.5 percent in 1952–1978 and 3.8 percent in 1978–2005.

8. There are different explanations for the pervasive distortions in developing countries. Acemoglu et al. (2005), Engerman and Sokoloff (1997), and Grossman and Helpman (1996) proposed that these distortions were caused by the capture of government by powerful vested interests. Lin (2012a, 2009, and 2003) and Lin and Li (2009) propose that the distortions were a result of conflicts between the comparative advantages of the economies and the priority industries that political elites, influenced by the dominant social thinking of the time, targeted for the modernization of their nations.

9. In spite of its attempt to implement a shock therapy at the beginning, Poland did not privatize its large state-owned enterprises until very late in the transition.

10. In the 1980s, the former Soviet Union, Hungary, and Poland adopted a gradual reform approach. However, unlike the case in China, their state-owned firms were not allowed to set the prices for selling at markets after fulfilling their quota obligations and the private firms’ entry to the repressed sectors was subject to severe restrictions, but the wages were liberalized (while in China the wage increase was subject to state regulation). These reforms led to wage inflations and exacerbated shortages. See the discussions about the differences in the gradual approach in China and the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in Lin (2009: 88–9).

11. Many of China’s problems today including environment degradation and the lack of social protections are generic to developing countries. In this section, I will only focus on a few prominent issues that arose specifically from China’s dual-track approach to transition. The collective volume edited by Brandt and Rawski (2008) provides excellent discussions of other development and transition issues in China.

12. Before the transition, the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) obtained their investment and operation funds directly from the government’s budgets at no cost. The government established four large state banks in the early 1980s, when the fiscal appropriation system was replaced by bank lending, and later the equity market. The interest rates have been kept artificially low in order to subsidize the SOEs. Prices of natural resources were kept at an extremely low level so as to reduce the input costs of heavy industries. In return the mining firms’ royalty payments were waived. After the transition, the natural resources’ prices were liberalized in the early 1990s but royalties remained nominal to compensate for the transfer of pension provision for retired workers from the state to the state-owned mining companies. However, the private and joint-ventured mining companies, which did not enter until the 1980s and thereafter, did not have any pension burdens. The low royalty payment was equivalent to a direct transfer of natural resource rents from the state to these companies, which made them highly profitable. The rationale for giving firms in the telecommunication and power sectors a monopoly position before the transition was that they provided public services and made payments on large capital investment. Due to rapid development and fast capital accumulation after the transition, capital is less of a constraint now but the Chinese government continues to allow the service sector to enjoy monopoly rents (Lin et al. 2003; Lin 2012a).

13. The national statistics used in this and the next paragraphs are taken from Maddison (2010).

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., and Robinson, J. A. (2005) ‘Institutions as the Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth’, in Handbook of Economic Growth, vol. 1A (eds.) P. Aghion and S. N. Durlauf, 385–472. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Bergsten, C. F. (2007) ‘Currency Misalignments and the U.S. Economy’, statement before the US Congress, May 9 <http://www.sasft.org/Content/ContentGroups/PublicPolicy2/ChinaFocus/pp_china_berg-sten_tstmny.pdf>.

Brandt, L. and Rawski, T. G. (eds.) (2008) China’s Great Economic Transformation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chang, G. H. (2001) The Coming Collapse of China, New York: Random House.

Chang, H. (2003) Kicking away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective, London: Anthem Press.

Easterly, W. (2001) The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists’ Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Engerman, S. L. and Sokoloff, K. L. (1997) ‘Factor Endowments, Institutions, and Differential Paths of Growth among New World Economies: A View from Economic Historians of the United States’, in How Latin America Fell Behind (ed.) S. Haber, 260–304. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Fei, J. and Ranis, G. (1997) Growth and Development from an Evolutionary Perspective, Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Gerschenkron, A. (1962) Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective: A Book of Essays, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Goldstein, M. (2010) ‘Confronting Asset Bubbles, Too Big to Fail, and Beggar-thy-Neighbor Exchange Rate Policies’, paper based on remarks delivered on December 15, 2009, at the workshop ‘The International Monetary System: Looking to the Future, Lessons from the Past’ sponsored by the International Monetary Fund and the UK Economic and Research Council, Peterson Institute of International Economics, 2010.

Grossman, G. M. and Helpman, E. (1996) ‘Electoral Competition and Special Interest Politics’, Review of Economic Studies, 63(2): 265–286.

Krugman, P. (2009) ‘World Out of Balance’, New York Times, November 15.

Krugman, P. (2010) ‘Chinese New Year’, New York Times, January 1.

Kuznets, S. (1966) Modern Economic Growth: Rate, Structure and Spread, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lal, D. and Mynt, H. (1996) The Political Economy of Poverty, Equity, and Growth: A Comparative Study, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Landes, D. (1998) The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor, New York: Norton.

Lau, L. J., Qian, Y., and Roland, G. (2000) ‘Reform without Losers: An Interpretation of China’s Dual-Track Approach to Transition’, Journal of Political Economy 108(1): 120–143.

Lewis, W. A. (1954) ‘Economic Development with Unlimited Supply of Labour’, Manchester School of Economic and Social Studies 22(2): 139–191.

Lin, J. Y. (1992) ‘Rural Reforms and Agricultural Growth in China’, American Economic Review 82(1): 34–51.

Lin, J. Y. (1995) ‘The Needham Puzzle: Why the Industrial Revolution Did Not Originate in China’, Economic Development and Cultural Change 43(2): 269–292.

Lin, J. Y. (2003) ‘Development Strategy, Viability and Economic Convergence’, Economic Development and Cultural Change 53(2): 277–308.

Lin, J. Y. (2009) Economic Development and Transition: Thought, Strategy, and Viability, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lin, J. Y. (2011) ‘New Structural Economics: A Framework for Rethinking Development’, The World Bank Research Observer 26(2): 193–221 (included in Lin 2012b).

Lin, J. Y. (2012a) Demystifying the Chinese Economy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lin, J. Y. (2012b) New Structural Economics: A Framework for Rethinking Development and Policy, Washington, DC: World Bank.

Lin, J. Y. (2012c) The Quest for Prosperity: How Developing Countries Can Take off, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lin, J. Y. and Li, F. (2009) ‘Development Strategy, Viability, and Economic Distortions in Developing Countries’, Policy Research Working Paper 4906, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Lin, J.Y. and Monga, C. (2010) ‘The Growth Report and New Structural Economics’, Policy Research Working Paper 5336, World Bank, Washington, DC (included in Lin 2012b).

Lin, J.Y. and Monga, C. (2011) ‘Growth Identification and Facilitation: The Role of the State in the Dynamics of Structural Change’, Development Policy Review 29(3) (included in Lin 2012b: 264–290).

Lin, J.Y. and Tan, G. (1999) ‘Policy Burdens, Accountability, and Soft Budget Constraints’, American Economic Review 89(2): 426–431.

Lin, J. Y., Cai, F., and Li, Z. (2003) The China Miracle: Development Strategy and Economic Reform, Hong Kong SAR, China: Chinese University Press.

Maddison, A. (2001) The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective, Paris: OECD Development Centre.

Maddison, A. (2007) Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run – Second Edition, Revised and Updated: 960–2030 AD, Paris: OECD Development Centre.

Maddison, A. (2010) Historical Statistics of the World Economy: 1–2008 AD. <www.ggdc.net/maddison/>

National Statistical Bureau (1991) China Statistical Yearbook, 1991, Beijing: China Statistical Press.

National Statistical Bureau (2009) China Compendium of Statistics 1949–2008, Beijing: China Statistical Press.

National Statistical Bureau (2012) The China Statistical Abstract 2012, Beijing: China Statistical Press.

Naughton, B. (1995) Growing out of the Plan: Chinese Economic Reform, 1978–1993, New York: Cambridge University Press.

North, D. (1981) Structure and Change in Economic History, New York: Norton.

Perkins, D. H. and Rawski, T. G. (2008) ‘Forecasting China’s Economic Growth to 2025’, in China’s Great Economic Transformation (eds.) L. Brandt and T. G. Rawski, 829–885. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Prebisch, R. (1950) ‘The Economic Development of Latin America and Its Principal Problems, New York: United Nations’, reprinted in Economic Bulletin for Latin America 7, no. 1 (1962): 1–22.

Ravallion, M. and Chen, S. (2007) ‘China’s (Uneven) Progress against Poverty’, Journal of Development Economics, 82(1): 1–42.

Subramanian, A. and Roy, D. (2003) ‘Who Can Explain the Mauritian Miracle? Mede, Romer, Sachs, or Rodrik?’, in In Search of Prosperity: Analytic Narratives on Economic Growth (ed.) D. Rodrik, 205–243. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sun, Y. S. (1929) The International Development of China (Shih yeh chi hua). 2nd ed. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

World Bank (on behalf Commission on Growth and Development) (2008) The Growth Report: Strategies for Sustained Growth and Inclusive Development, Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank (2010) World Development Indicators, 2010, Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank (2012) World Development Indicators, 2012, Washington, DC: World Bank.