Figure 12.1 Share of gross industrial output value by ownership (1978–1993)

Source: Calculated using data from China Statistics Yearbook in various issues

12

STATE AND NON-STATE ENTERPRISES IN CHINA’S ECONOMIC TRANSITION

China’s enterprise system reform constitutes a key part of its economic transition from a centrally planned to a market-based economy. The reform process began in 1978 and has continued right through the first decade of the twenty-first century and beyond. The key elements in enterprise system reform consist of the ownership reform of the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the development of the non-state enterprises including both foreign-funded firms and indigenous private firms. The ownership reform in the state sector has unleashed strong productive forces through improved incentives that, together with the rising private sector, have formed the micro-foundation for the rapid economic growth in China over the past thirty years. The reform has nurtured rising entrepreneurship which has in turn injected further dynamics into the system powering the strong growth of the Chinese economy. These reforms have led to the changes in the relative importance of the state versus the non-state sector, with an increasing share of the non-state sector in the total economy. To accommodate these fundamental changes taking place in its enterprise system China has been reforming its institutions, such as the financial and banking system, labor market system, local government system and the legal system. The significance of the enterprise system reform in China is that the private sector has now contributed more than 60 percent of China’s GDP, more than 80 percent of the total industrial value added, and more than 97 percent of its total workforce employed.

There are, however, some key unfinished tasks in reforming both the state and the non-state sector such as the state-enterprise relationship, state monopoly and competition, corporate governance, business finance and the regulatory system governing the enterprise system. There is also a need to both nurture entrepreneurship through improving the way that the market functions and to further develop China’s legal system and the enforcement of court decisions. The difficulties in accomplishing those tasks lie in the existing institutions that, despite the progress made to change them in the past, have still not been entirely compatible with what a market system requires. Overcoming these difficulties by deepening institutional reform holds the key for China to complete its tasks of enterprise system reform and through that to sustain long-term growth and development. Failure to do so will see rising distortions and inefficiency in resource allocations which are inconsistent with the ultimate objective of an economic transformation that is designed to achieve an improved standard of living for the Chinese people in the most efficient and equitable way.

This chapter reviews the progress made so far in reforming China’s enterprise system by dividing the reform into three stages, highlighting the key issues involved in each stage and their impact on China’s economic performance. The chapter then identifies the unfinished tasks in reforming the system and points the way forward.

Before reform, almost all enterprises in China were SOEs or collectively owned enterprises which were wholly or mainly owned and directly or indirectly controlled and managed by either the central or local governments. In particular, the governments set the SOEs’ production targets, as well as all inputs of factors of production (such as labor and raw materials used in production) according to the state plan. Managers of SOEs had no role in deciding what to produce or at what prices their inputs of factors of production should be purchased and their final products be sold. Planning mechanisms replaced market mechanisms in the operation of Chinese enterprises. The consequences of such a system were low efficiency of SOEs resulting from the lack of incentive on the part of managers as well as workers, the stagnation of industrial production because of the misallocation of resources, and the shortage of manufacturing products for consumption due to the distortions in its price system. Economic studies have concluded that there was stagnant or even declining total factor productivity (TFP) in the SOE sector in the pre-reform period (World Bank 1995; Chow 2002; Zhu 2012).

Since China officially adopted the reform policy in 1978, the Chinese government has taken a gradual, experimental and pragmatic approach to reforming SOEs and letting the private economy exist, develop and flourish. The industrial system reform centering on SOEs was carried out following the successful reform in rural areas which aimed to provide incentives to farmers by granting them production responsibility and by partially liberalizing the planned prices for agricultural products (Lin 1992). Similarly, the core elements in industrial reform involved the granting of autonomy to enterprises through various kinds of enterprise system reform. These included ownership reform, liberalizing the prices for industrial products, and handling the rising social tension resulting from the massive retrenchment in the state sector (Garnaut et al. 2006).

This gradual and ongoing reform process can be divided into three stages. At each stage, the relative performance of both SOEs and non-SOEs is discussed, and more importantly each stage of reform reveals how the development of the non-state sector has been influenced by the progress in reforming the SOE sector.

In December 1978, the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (hereafter “the Party”) declared that: “a serious shortcoming in the economic management system in China is that the power is too centralized, thus bold decentralization should be carried out under the leadership, so that local industrial and agricultural enterprises can obtain more autonomy in their business management under the guidance of national planning.” Under this guideline, in May 1979, the State Economic and Trade Commission and six ministries selected eight enterprises in Beijing, Tianjin and Shanghai to start a pilot program on granting autonomy of management to enterprises. In July 1979, the State Council issued a series of documents on the expansion of the autonomy of operation and management and the profit retention requirements of SOEs. In 1980, the number of pilot enterprises increased to 6,000, accounting for about 16 percent of the national budget, 60 percent of the gross industrial output value, and 70 percent of the total industrial profits (Chen 2008).

The implementation of the managerial system reform and profit retention under the program of decentralization stimulated enterprises to increase production. However, since the pilot program of decentralization lacked clear responsibilities for managers and sufficient macroeconomic institutions to regulate the process, China encountered a huge budget deficit for two consecutive years in 1979 and 1980. To solve this problem, in 1981, the central government launched the “economic responsibility system,” under which managers were given an incentive to keep part of the profits above what was set in their contract with the government. In May 1984, the State Council issued the Regulation on Further Expanding Autonomy of State-owned Enterprises, which granted SOEs more autonomy in making a production plan and for profit retention. The government also realized that for the decentralization program to work, the centrally controlled pricing system had to be changed, which led to price liberalization, a crucial element in economic reform and transformation.

In January 1987, the government started promoting the “contract responsibility system” and the “dual-track price system,” which allowed SOEs to sell their products that exceeded the planned quotas at market prices. This measure gave SOE managers financial incentives to produce more. This market-oriented reform measure set in train a series of crucial developments within the enterprise system, as well as China’s nascent market system. By the end of 1987, about 80 percent of the large and medium-sized SOEs had adopted the “contract responsibility system,” and by 1989 almost all SOEs adopted this system (Chen 2008). Under the “dual-track price system,” the market started playing its role of allocating resources alongside the planning mechanism. This is what Naughton (1992) called “China is growing out of the plan” (without radically shifting its ownership structure). In July 1992, the State Council issued the Regulation on Transforming the Management Mechanism of State-owned Industrial Enterprises, granting SOEs more rights in setting their own prices and wages, hiring and firing labor, determining investment of fixed capital, and engaging in foreign trade. The Regulation gave SOEs more bargaining power to negotiate with governments and even to resist government interferences. After the Regulation was issued, many SOEs began laying off workers in order to cut their burdens and improve their business performance. These reform measures started changing the relationship between the governments and enterprises with the latter becoming more and more independent in decision-making at the enterprise level. At the same time, the governments began facing the issues of rising unemployment and started working on compensation schemes for those who were losing jobs in the enterprise restructuring. This task became more and more necessary as the ownership reform deepened at later stages of the reform.

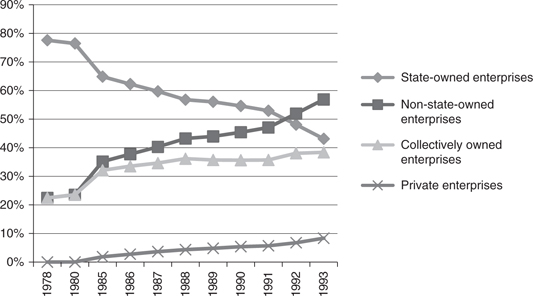

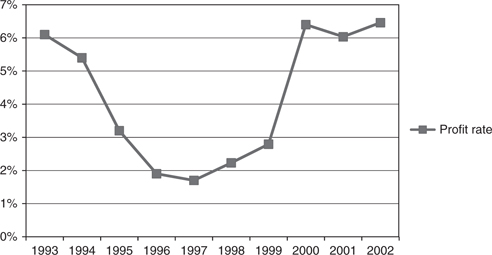

The first stage of reform produced some positive outcomes. In 1978, SOEs still played a predominant role in the economy, accounting for about 80 percent of the total industrial output and employing the majority of the urban labor force (Figures 12.1 and 12.2). However, their importance in the economy declined gradually and steadily over time. Figure 12.1 shows that the share of SOEs in gross industrial output value declined from 78 percent in 1978 to 48 percent in 1992, when for the first time the non-state sector (mainly comprising collectively owned private and other types of enterprises) surpassed the state sector. This is a significant change as it is consistent with the goal of economic transition, namely to increase the share of the non-state sector in the total economy in order to establish a market system.

Figure 12.1 Share of gross industrial output value by ownership (1978–1993)

Source: Calculated using data from China Statistics Yearbook in various issues

The majority of the non-state sector was made up of collectively owned enterprises, mainly involving those urban enterprises that were not state-owned, as well as township and village enterprises (TVEs) located in rural areas. Collectively owned enterprises are usually legally owned by their workers and other economic entities, but in practice local governments often play a controlling role in their management (OECD 2000). The State Council first used the term “TVE” (xiangzhen qiye) in 1984. These enterprises were previously known as “Commune and Brigade Enterprises” dating from the “Great Leap Forward” period from 1958 to 1961. During that time, TVEs had a limited role and were restricted to the production of iron, steel, cement, chemical fertilizer, hydroelectric power, and farm tools. Starting from the early 1980s, TVEs were largely detached from central planning requirements and their growth was promoted by local authorities, in order to encourage rural employment and to provide revenues to local governments (OECD 2000).

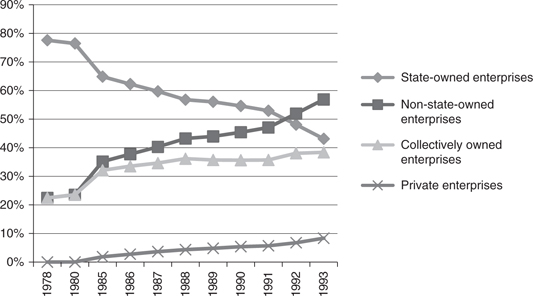

Figure 12.2 Profits and losses of SOEs (1985–1993)

Source: Calculated using data from China Statistics Yearbook in various issues

Notes: Profit rate (left axis): total profits divided by net value of fixed assets. Loss ratio (right axis): total losses of loss-making firms divided by net value of fixed assets

Figure 12.1 also shows that the share of private enterprises in total gross output value was still relatively small although steadily increasing at this stage of reform. Private enterprises remained marginal or supplementary in China’s national economy for a relatively long time after reform began, even after their legitimate status was clearly established in the Constitution in 1999. Private ownership itself made these firms vulnerable to a variety of discriminating treatments partly due to the legacies of central planning which favored the state sector. The governmental agencies especially at local levels, such as those dealing with taxation, industrial and commercial administration and registration, technology and quality control, and hygiene, would scrutinize private firms more carefully or frequently but would be relatively more lenient to state-owned and collectively owned enterprises when violations occurred in these firms. Among the emerging private firms, there was still a profound distrust of the stability of and consistency in the state policies toward private economy during the first stage of reform. In what was known as “wearing a red hat,” many private firms disguised themselves as either state-owned or collectively owned so as to have easier access to bank loans or land, have the privilege of engaging in imports and exports, using public resources and facilities, and escaping from harassment by local officials. Local officials could in turn obtain considerable funds from private firms, not only through formal means such as taxation, but also by collecting various kinds of fees which were in many cases at the discretion of the local officials, thus increasing their local revenues and employment. The main problem with such disguised relations became prominent when disputes between governments and enterprises appeared due to the ambiguities of their relations in terms of their respective ownership over assets and their shares of profits (Garnaut et al. 2001).

The first stage of reform granted more autonomy and financial incentives to SOE managers. However, the SOEs’ financial performance did not improve very much and in fact they even declined after the mid-1980s. By this standard, the SOE reform was far from being satisfactory. Figure 12.2 shows that the profit rates of SOEs had been declining from 1985 to 1993. The SOE profit rate (total profits divided by net value of fixed assets) was about 18 percent in 1985 but had fallen to below 6 percent during the early 1990s. This declining trend was substantially attributable to increasing competition caused by the entry of non-SOEs, but also to the incompleteness of the SOE reform itself which affected their performance. Other indicators of SOE performance had also deteriorated over time. Total losses of loss-making SOEs rose sharply during the latter half of the 1980s and reached their peak in relation to output in 1990 (Figure 12.2). The number of SOEs running at losses was also rising, and the amount of total losses was increasing. Due to the wide scope and huge amount of losses in the state sector, the government’s subsidy to SOEs also swelled, taking a 37 percent jump from 1986 to 1992 (Chen 2008). As expected, the SOEs’ contribution to the government’s revenue was also declining during that period. The loss-making by SOEs and the loss of revenues on the part of the governments worsened the governments’ budgetary positions. Therefore, further reform that could protect the state’s interests and rights while increasing SOE managers’ incentives was desired.

To find a solution for deepening SOEs’ reform, it is important to understand what the problems associated with the first stage of SOE reform were. The SOEs were owned by the state but run by managers and workers. The separation of ownership and management control led to at least three common problems that may arise in any enterprise with the separation of ownership and management control (Lin 1998; Chen 2008).

First, “incentive incompatibility”: the owner and the manager of the enterprise had different goals and interests. The owner always intended to obtain the largest possible return from his investment, while the manager wanted to maximize his personal income and welfare. Because of the incentive incompatibility, the manager had the incentive to engage in opportunistic behavior that benefited the manager, possibly at the expense of the owner.

Second, “information asymmetry”: the owner was not involved in the production process and did not have direct information about the material requirements, actual expenditures, revenues, and so on. Because of the information asymmetry, the potential opportunistic behavior could become a reality. In the case of SOEs, the managers might have required more inventories, used more inputs, and reduced the profits submitted to the state by overstating costs and/or underreporting revenues. When initial reforms were taking place involving decentralization and price liberalization, there were ample opportunities for the managers to take advantage of this partially reformed system to make profits for themselves.

Third, “disproportional liability”: the punishment that the owner could impose on a manager of a failed enterprise was disproportionate to the value of the enterprise. Therefore, the manager might engage in investing in overly risky projects. If the projects succeeded, the manager might gain very high rewards. If the projects failed, the enterprise might be bankrupt in which case the manager’s loss might be proportional to the owner’s loss.

Moreover, the first stage of economic reform provided an opportunity for the rise of TVEs, private firms, joint ventures with foreign firms, and other non-SOEs whose development before the reform was suppressed because of their lack of access to both inputs and output markets. Market competition appeared as a result. Without state subsidies and protection, the non-SOEs’ survival depended on their own strength in market competition. Non-SOEs were more adaptive to market and flexible in management. With the enlargement of the non-state sector and the shrinkage of the state sector in terms of output share, SOEs were under growing competitive pressure.

Nevertheless, SOEs still had to bear many policy-determined burdens that went well beyond the levels that enterprises typically provide in other market economies, including redundant labor that enterprises were not free to shed, disproportionately high tax burdens, and expenses for social benefits such as medical care, pensions, housing, and education. The large SOE policy burdens were a major reason for their profitability to remain relatively low (Lin et al. 1998). Policy burdens were mostly a legacy of prior central planning mechanisms but their persistence is substantially attributable to structural problems such as the lack of national social security systems and social supporting programs and the scarcity of government revenues for providing public goods. For the reasons mentioned above, SOEs were in a disadvantageous position in competing with non-SOEs. The existence of such causes made it harder to distinguish the SOEs’ losses between those arising from policy legacies and those from mismanagement. The profit level of an SOE could not serve as sufficient information or criteria in measuring its managerial competency and efficiency. The costs for the state to monitor the manager of an SOE were extremely high because, under the price-distorted economic environment in China, the profits or losses of an SOE would not reflect its managerial performance and there existed no other simple, sufficient indicator of the manager’s efficiency in performance under this circumstance. Since the information asymmetry problem was not overcome, managerial decentralization increased the possibility of manager’s opportunistic behavior. Especially with the existence of a dual-track price system, it was very easy for SOEs to under-report revenue and over-report costs without being detected. As a result, the SOEs’ taxes that were paid to the state and the SOEs’ profits that were shared by the state were both declining, even though managerial decentralization improved the SOEs’ productivity.

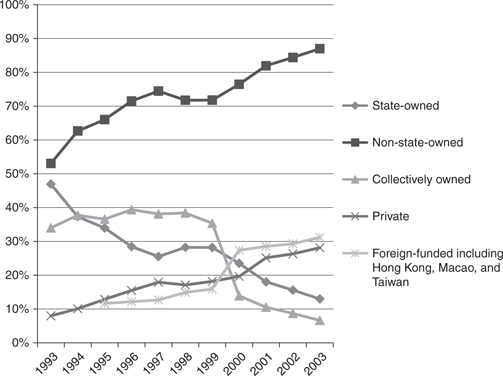

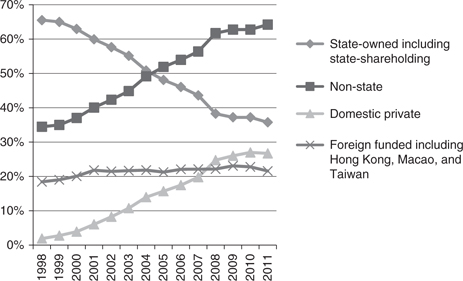

The earlier reform of SOEs was successful in improving the incentives of managers and freeing the government from direct involvement in the management of SOEs. Because the “contract of responsibility” of managers needed to be renegotiated every three years and the insiders had more control over the terms of the contract, it promoted short-term behavior by the managers. In fact, despite the reform, SOE performance deteriorated further from 1993 to 1997 (Figure 12.4). Policy makers and many researchers in China believed that the major problems of SOEs were unclearly defined property rights, continued government interference in enterprise management, and so on. In the subsequent SOE reform, a major focus was given to clarify property rights through ownership transformation (Gaizhi), such as privatization of small and medium-sized SOEs, and the separation of government ownership and regulatory functions from the direct interference and management of large SOEs.

In November 1993, the Third Plenum of the Fourteenth Party Congress adopted the Decision on Issues Concerning the Establishment of a Socialist Market Economic Structure, which provided a package of reform measures to carry out the vision of a “socialist market system” set forth by the Fourteenth Congress. The Decision set forth the task of transforming SOEs into “modern enterprises” with “clarified property rights, clearly defined responsibility and authority, separation of enterprises from the government, and scientific internal management.” It also allowed for the privatization of small and medium-sized SOEs to take place. “As for the small state-owned enterprises, the management of some can be contracted out or leased; others can be shifted to the partnership system in the form of stock sharing, or sold to collectives and individuals.”

Privatization started in earnest after a visit by Deng Xiaoping to southern China in 1992, while privatization of small SOEs occurred on a large scale in 1995. By the end of 1996, over half of the small SOEs were privatized. Over this period, over ten million workers were laid off as a result of SOEs ownership reform and restructuring. In September 1997, the Fifteenth Party Congress issued the Decisions on Issues Related to State-Owned Enterprise Reforms and Development, officially recognizing that “China is a mixed economy in which a variety of ownership forms, including private ownership, co-exist.”

The Fifteenth Party Congress further promoted the privatization of small SOEs by putting forward the slogan: “grasping the large (SOEs), letting go the small (SOEs)” (Zhua Da Fang Xiao). This was an important measure because most of China’s SOEs fell in the category of “small or medium size,” and only about 1,000 SOEs were considered “large scale” with a need to remain state owned. The large SOEs were encouraged to form business groups through various kinds of internal restructuring aimed at increasing their efficiency in management and operation. The status of the private sector was further strengthened in March 1999 by the Ninth National People’s Congress, which approved a constitutional provision upgrading the non-state sector from an “important complement” to a state-dominated economy to an “essential component” of a mixed economy.

Since 2000, the reform of China’s SOEs has accelerated and acquired some qualitatively new features. First, the scale of change has expanded to affect almost every kind of SOE – small, medium, and large ones who are under both the central and local government control. Second, ownership diversification has been so extensive that the wholly state-owned nonfinancial enterprise has become rare. Third, the range of restructuring mechanism being used has expanded dramatically to include bankruptcies, liquidations, listings, sales to private firms, auctioning of state-owned firms and their assets or liabilities, and so on. By the end of 2001, about 86 percent of SOEs went through Gaizhi and about 70 percent were partially or fully privatized (Garnaut et al. 2005).

Through the second stage of reform, the number of SOEs declined from 104,700 in 1993 to 29,449 in 2002.2 According to Garnaut et al. (2005), about two-thirds of the decline was due to privatization. Privatization in China was not limited to small enterprises only: the average size of privatized SOEs was about 600 employees. The process had been socially painful: more than thirty million SOE workers had been laid off from 1998 to 2002. Meanwhile, a dynamic de novo private sector has been able to absorb most of the laid-off workers, thus alleviating the social cost of restructuring. The governments have also done their part in easing the social tension by establishing the re-employment centers that accommodated those who lost their jobs through restructuring.

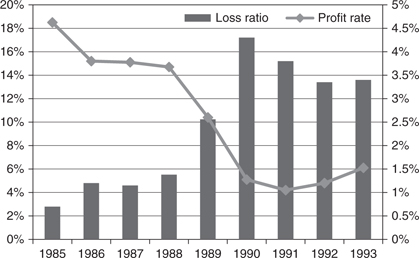

As the reform progressed, the significance of SOEs in the economy in terms of total gross output value continued to decline, giving way to the rapidly growing TVEs during the 1980s (Figure 12.1) and to the even more explosive growth of foreign-funded and privately owned enterprises during the 1990s (Figure 12.3). The importance of collectively owned enterprises declined dramatically after 1999 because the central government issued a policy in November 1998 to encourage firms registered as collectives but in reality privately run to take off the “red hats.” By the end of 1999, more than 80 percent of state and collective firms at the local level had gone through Gaizhi, which involved direct privatization in most cases (Garnaut et al. 2006). The private firms and foreign-funded firms increased rapidly during the 1990s, and eventually replaced the collectives to become the major type of non-SOEs in China.

Figure 12.4 shows the change of the profit rates of SOEs during the second stage of reform from 1993 to 2002. The annual SOE profit rate (total profits divided by net value of fixed assets) continued its declining trend until 1997, when it reached the lowest point, at only about 1.7 percent, and then rebounded rapidly back to 6 percent in 2000, keeping this level steady for the next two years. This significant change was substantially attributable to the progress made in reducing SOEs’ overhead burdens and more substantially through ownership reform during the second stage of reform.

SOEs were not alone in experiencing weak financial performances in the 1990s. According to the estimates made by the OECD, profit rates for collectively owned and private enterprises as a whole were also relatively low by international standards. A high proportion of collectively owned firms were also experiencing losses, although the fraction was only about half that of SOEs (OECD 2000). Furthermore, the profitability of foreign-funded enterprises, while it had been substantially higher than that of the other segments in the economy, had fallen markedly from 15 percent of assets in 1995 to 4 percent in 1996–97 (World Bank 1999) but back to 15 percent in 2002 according to the China Statistics Yearbook from 2000. These low profit rates of SOEs and non-SOEs before 1997 suggested there might be serious structural problems in terms of both supply and demand in the Chinese economy at that time.

Figure 12.3 Share of gross industrial output value by type of ownership (1993–2003)

Source: Calculated using the data from China Statistics Yearbook in various issues

Notes: The share of private enterprises in gross industrial output value 2000–03 are estimates as the China Statistics Bureau only included private enterprises above a designated size into their statistics since 2000

The Chinese government had further pushed forward the economic transformation of SOEs (Gaizhi) during its second stage of economic reform from 1993 to 2002. Over this decade or so, the Chinese economy had made the transition from being completely reliant on state-owned and collectively owned enterprises to a mixed economy where private enterprises played a leading role. According to the estimates made by Garnaut et al. (2005), the private sector became the largest sector of the Chinese economy, accounting for about 37 percent of gross domestic product in 2003. Overall, the non-state sector accounted for about two-thirds of China’s GDP in 2003.

The use of the term “Gaizhi,” instead of “privatization,” during the second-stage reform illustrated the cautious approach taken by the central government. The central government’s main concerns were that Gaizhi might lead to the loss of state assets and bank loans owed and unpaid to the state banks, and possible social unrest trigged by massive unemployment resulting from large-scale privatization. The Chinese public was concerned that private companies and SOE managers might enrich themselves at the expense of the state and society at large. The policy response has been to introduce regulations on the restructuring SOE process and to strengthen their enforcement. There was a need to build an effective and transparent asset valuation system to achieve a fair and smooth transfer of state assets. However, the administrative capability to handle state assets, both within the government and within firms, was often inadequate and needed to be strengthened. Nonetheless, a properly managed transfer of assets from the state to private owners was a crucial part of the Gaizhi process, with strong implications for preventing losses of state assets and maintaining social stability in the transition.

Figure 12.4 Annual profit rates of SOEs (1993–2002)

Source: Calculated using the data from China Statistics Yearbook in various issues

During the process of Gaizhi, a large number of SOE employees were laid off. Between 1995 and 2003, the number of SOEs fell from 118,000 to around 34,000, and total employment in the SOE sector fell by around 44 million. The number of lost state-sector jobs totaled 17 percent of urban employment in 2003 (Garnaut et al. 2005). The Chinese central government pressured local governments to adopt every possible means to maintain employment, and thus social stability, during Gaizhi. This created a conflict of interest between the central and local governments over the responsibility for the costs of Gaizhi. Some local governments did not have the resources to compensate all SOE employees and so offered discounts on state assets to potential buyers of state firms in order to avoid resistance to the process of Gaizhi.

Two economic factors emerged as being critically important in alleviating the social cost of Gaizhi: the development of the national social security system and the promotion of the growth of new private enterprises to absorb laid-off workers from the state sector. There was a significant increase in central budget expenditures on social security from 1993 to 2002: from less than 1 percent in 1993 to 6.3 percent in 2002. Significant progress was made in reducing enterprise overhead burdens during the second-stage reform, but not sufficient alone to ensure a lasting improvement in enterprise competitiveness.

Domestic private enterprises became one of the major players in the Chinese economy during the second stage of reform (Figure 12.3). At the beginning of the second stage of reform, private enterprises were supporting SOE restructuring, largely indirectly, by creating the jobs needed to absorb laid-off workers. While this indirect role continued to be important, domestic private enterprises emerged as significant players in the privatization process. A growing number of private enterprises began to look at acquisitions of SOEs as their main growth strategy. These private firms injected capital and dynamism into moribund SOEs thus helping to preserve jobs. The second stage of reform characterized by SOEs’ ownership transformation (Gaizhi) brought about efficiency-enhancing changes in China’s state enterprise sector (Garnaut et al. 2005). While the successes of Gaizhi were significant, the potential harmful social impact associated with restructuring on such a massive scale also attracted public attention. The efforts at enterprise restructuring still had a further way to go and the financial gains to enterprises depended on progress in capabilities to generate profits. Measures to upgrade technology and product quality and to improve industry organization have been the keys to lasting improvements in enterprise efficiency. Reforms in these areas were in some respects more difficult and subject to greater constraints than reforms to reduce overhead burdens.

During the second stage of economic reform from 1993 to 2002, China was preparing for and finally joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. WTO membership was generally perceived as beneficial by China, given the welfare gains from a more open economy as predicted by economic theory (Drysdale and Song 2000). However, some sectors of the economy, especially SOEs which remained rather inefficient and relied heavily on government subsidies, were concerned about the negative impact caused by the increased competition derived from membership in the WTO. Nonetheless, by the late 1990s, almost the entire SOE sector was in debt and the state banks were on the verge of insolvency burdened with non-performing loans resulting from the lending to SOE firms. In view of this situation, China had to further implement deeper reforms that included further privatization and deregulation (Bajona and Chu 2004).

The WTO is a multilateral trading system, which lays out the legal ground rules for international commerce. By gaining access to the WTO, China was forced to be in line with the international standard in many aspects of a market-based economy and to provide a relatively level playing field for all market participants including both foreign and domestic firms. The latter includes both the state and non-state enterprises. A series of domestic laws, regulations and market rules had to be changed and adjusted for the accession to the WTO. Particularly, upon accession China committed to partially eliminate state subsidies to SOEs and to eventually let all SOEs operate on a commercial basis, making them responsible for their own profits and losses. Hai (2000) explicitly pointed out that one important implication of China’s WTO accession was to accelerate the reform of the SOEs and to help develop private enterprises in the Chinese economy.

China’s WTO accession played an important role in supporting domestic reforms even before its formal accession in December 2001, as the Chinese government had decided to allow private ownership to take place throughout all sectors in order to become a member of the WTO. In this way, the WTO accession easily solved issues related to the status of domestic private firms: if national treatment was to be granted to foreign companies there was no excuse not to grant national treatment to domestic private enterprises (Bajona and Chu 2004). Through WTO accession, domestic private sectors, despite their weak political voices, were further promoted to become a growing part of the Chinese economy.

The Chinese government has used WTO membership as an instrument to lay down a framework for economic reform and to bring external forces toward the implementation of domestic reforms, including the difficult SOE reform. For example, the WTO agreement makes direct subsidies to SOEs more difficult to implement. Moreover, by requiring a more open financial sector, WTO membership forces banks to be more profit-oriented and to reduce lending to non-performing SOEs. Both factors combined to promote the restructuring of the SOE sector and the closing of inefficient SOEs (Bajona and Chu 2004). At the time of accession, SOEs still represented 60 percent of the total fiscal revenues and were deeply vested in various government agencies. The reform was expected to encounter strong resistance if it confronted all these vested interests directly. However, by tying the domestic reforms together with the accession to the WTO, the SOE reforms became an obligation to fulfill and an international commitment.

During this latest stage of reform, deepening ownership reform and improving corporate governance became the main targets of SOE reform. For the management of remaining large SOEs, the government established the State-Owned Asset Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) in March 2003, representing the state in performing its duty and exercising its rights as the owner through its management of assets, personnel, and operations. Local SASACs were set up at provincial level in 2004 to manage local-level SOEs.

In October 2003, the Third Plenum of the Sixteenth Party Congress issued the Decision on Issues of Perfecting Socialist Market Economy System, which made a few ideological breakthroughs that were to have a profound impact on the further development of China’s corporate governance system. For the first time, the Party acknowledged property rights as the “core issue” of ownership reform and made building a “modern system of property rights” an important task of future reform. Second, the Party redefined public ownership in a socialist economy and made “shareholding companies” the main organizational form of public ownership. The Party further made promotion of “mixed economy” its main task in establishing a market system in China. Last but not least, private enterprises were promoted and allowed to operate on an equal footing in terms of business financing and taxation with SOEs.

Corporatization of SOEs has become an important reform measure taken by the government since the mid-1990s with the goal of building China’s own modern enterprises in a market system. After undergoing ownership reform, some SOEs went public. With the new ideological breakthroughs in 2003, more SOEs have turned into shareholding companies. In October 2007, in the report of the Seventeenth Party Congress, SOE reform was mentioned ten times. Deepening the SOE reform has been a top priority for China’s economic reform in recent years. By the end of 2010, the number of SOEs under the direct control of the central government was limited to 121, among which only twenty-two were corporatized according to the Corporation Law.

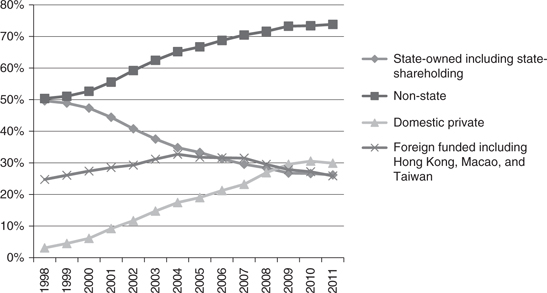

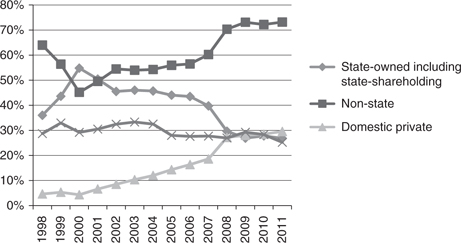

The non-state sector in China has experienced the developing process from virtual non-existence to existence and from weak to strong in the last three decades. SOEs contributed about 80 percent of the total industrial output in 1978, but the SOEs’ share of industry output has declined steadily to less than 30 percent since 2007. On the other hand, the non-state sector of the economy has become the most important engine of economic growth in China, as the non-state sector accounted for more than 73.8 percent of the total economic output value in 2011 (Figure 12.5). Non-SOEs have surpassed SOEs in many aspects of economic activity such as total employment, taxation, and industrial profits (Figures 12.6–12.8). Chinese domestic private enterprises have also become the major market force in the Chinese economy, surpassing the foreign-funded and SOEs in output (Figure 12.5). Nonetheless, the development of the non-state economy is still facing many problems, such as difficulties for small and medium-sized private businesses to get loans from the formal banking sector, inadequate human capital and technical investment of private enterprises, as well as unfair competition conditions caused by existing government regulations toward private and state operated enterprises such as market entry to certain industrial sectors and state monopolies.

Figure 12.5 Share of gross industrial output value by types of ownership above designated size (1998–2011)

Source: Calculated using the data from China Statistics Yearbook in various issues

Notes: Comparing Figure 12.5 with Figure 12.3, we find that there is an inconsistency in the share of gross industrial output value by types of ownership. It is because before 1998 all enterprises were included in the statistics, but since 1998, especially since 2000, only enterprises above designated size, whose annual sales revenue was over 5 million Yuan, were surveyed and reported. Moreover, in Figure 12.5, SOEs also includes state-shareholding ones, which also increases the share of SOEs in the total. For the statistics in year 1998 and 1999, both enterprises above and below designated size were reported (the same note applies to Figures 12.6–12.9)

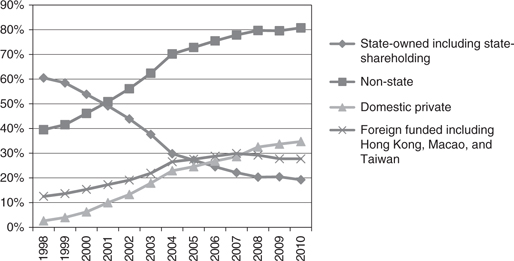

Figure 12.6 Annual average employment ratio by types of ownership above designated size (1998–2011)

Source: Calculated using the data from China Statistics Yearbook in various issues

Figure 12.7 Annual ratio of value-added tax payable by types of ownership above designated size (1998–2011)

Source: Calculated using the data from China Statistics Yearbook in various issues

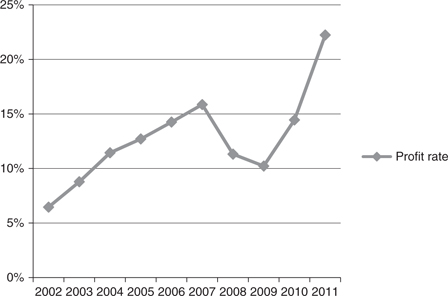

SOEs’ deteriorating financial performance turned better as the second stage of economic reform progressed. Profit rates had been declining from 1985 to 1997, but started to increase after 1997 (Figures 12.2, 12.4, and 12.9). Nevertheless, Li et al. (2012) largely attributed the rising profitability of SOEs in the first decade of this century to their enhanced monopolized market power. They showed that the upstream SOEs extracted rents from the liberalized downstream sectors in the process of industrialization and globalization. They implied that the relatively high profit rate in the past decade could be merely a growth-undermining symptom of the incompleteness of market-oriented reforms rather than proof of their efficiency dominance over non-SOEs.

Figure 12.8 Annual ratio of total profit by types of ownership above designated size (1998–2011)

Source: Calculated using the data from China Statistics Yearbook in various issues

Figure 12.9 Profit rates of SOEs (2002–2011)

Source: Calculated using the data from China Statistics Yearbook in various issues

Establishing an effective corporate governance system has become a key priority of China’s current enterprise reform, with an objective to establish and develop a “modern enterprise system.” Effective corporate governance ensures that the behavior of the managers is transparent, accountable and competitive, and firms can adapt to the changing demands of the market more efficiently. The Chinese government has tried to develop modern governance systems by pushing SOEs to restructure and reorient managerial incentives in order to engage in profit-oriented, value-augmenting activities, in line with social or public interests. Moreover, to cope with the increased competition from both domestic and international sources, China’s enterprises need to improve their decision-making mechanisms to compete successfully in domestic and international markets. Adoption of corporate governance mechanisms in line with international practice is also essential to the ability of China’s enterprises to attract foreign capital in increasingly competitive global capital markets. The development of China’s equity markets contributes to the improvement of corporate governance practice for those listed firms. However, further changes are much needed to improve the practice (Tenev and Zhang, 2002).

As domestic private enterprises have developed quickly and started to become a dominating force in China’s economy, how to improve their internal governance turns out to be a key issue for their success and sustainable development. Most private firms in China are owned by an individual or a family and also managed by the owners, or their relatives. However, as many private firms grow larger, the old family-type management style may not be suitable for their business development. Compared to the corporate governance of advanced economies, there is still a large gap for the Chinese domestic private companies to catch up. In recent years, there have been many examples of Chinese domestic private companies failing due to mismanagement.

Mature corporate governance goes beyond the simple purpose of making profit for companies. A modern company should have its corporate social responsibility combining both the interests of developing the company and caring for society. Morris Chang, Chairman and CEO of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), indicated on its website that TSMC tries to improve its performance in the following seven dimensions of “morals, business ethics, economy, rule of law, work/life balance, caring for the earth and the next generation, and philanthropy” in order to act as a good corporate citizen, inspire others to follow, and make society better.3 SOEs in China also increased corporate responsibility reports from five in 2006 to seventy-six in 2011.4 However, the number of Chinese enterprises demonstrating their corporate social responsibility is still very small.

Governance reform in China has involved a series of institutional and organizational transformations, such as establishment of a multi-tiered state asset management system, the introduction of boards of directors and other modern governance mechanisms into corporatized firms, and the promotion of corporate social responsibility. The success of the reforms in improving enterprise governance has been uneven: governance has improved most for SOEs in competitive sectors and much less, if at all, for those in protected industries (World Bank 2012). To improve corporate governance, the state shareholder and regulatory functions should be sufficiently separated in practice. It is also important to effectively protect the rights and obligations entailed in modern corporate governance mechanisms in China through strengthened institutional and regulatory enforcement.

Sustaining high growth poses a considerable challenge for China. In the past three decades, high levels of investment have been a major driving force of growth in China, but with population growth slowing rapidly and investment rates also declining, China’s future growth will be more dependent on gains in total factor productivity (TFP), as has been argued by the World Bank (2012) among others.

According to the estimates made by Zhu (2012), the average annual TFP growth rate for the Chinese state sector is 1.68 percent, while that for non-state sector is 3.91 from 1978 to 2007 (see Table 12.1). Zhu (2012) also separated the time-frame into three stages, which are roughly consistent with the three stages described in this chapter. As we can see from Table 12.1, from 1978 to 1988, the average annual TFP growth rate for the state sector was negative, indicating that the first stage of SOE growth was mainly due to the increases of capital and labor. Even up to 1998, the state sector still had very low productivity growth rates, reflecting the deteriorating performance of SOEs during that period. From 1988 to 1998, the productivity growth in the non-state sector also dropped to 2.17 percent from 5.87 percent during the period between 1978 and 1988, indicating there was a structural problem in China’s economy. After 1998, TFP in the state sector grew rapidly, averaging 5.5 percent annually and exceeding the average growth rate in the non-state sector, which is 3.67 percent. Zhu (2012) attributed the increase in TFP growth in state and non-state sectors after 1998 to the combined effects of privatization and trade liberalization.

| Average annual total factor productivity growth (%) | |||

| Period | Non-state | State | Aggregate |

| 1978–2007 | 3.91 | 1.68 | 3.61 |

| 1978–1988 | 5.87 | −0.36 | 3.83 |

| 1988–1998 | 2.17 | 0.27 | 2.45 |

| 1998–2007 | 3.67 | 5.5 | 4.68 |

Source: Zhu (2012)

To maintain relatively high TFP growth, China needs to further accelerate its industrial structural upgrading, speed up technological innovation, and create a more competitive and open economy. China’s President Hu Jintao first proposed to build an “innovative nation” in October 2005. In 2006, the Chinese government laid out a strategy for enterprise-led indigenous innovation (Zhang et al. 2009). As Zhang et al. (2009) pointed out, in implementing this strategy, China faces great challenges from its current development stage and economic transitional nature. First, Chinese enterprises must derive their competitiveness from innovation while continuing to create jobs for the huge Chinese labor force. Second, the major performers of R&D activities in China are SOEs and government-run research institutes, while private enterprises only accounted for 3.5 percent of total R&D expenditure in 2006. Third, the supporting market institutions, such as weak intellectual property protection, barriers to entry, exit, and fair competition, and an underdeveloped venture capital system, are not functioning well enough to promote innovation in China.

To overcome the above problems, Zhang et al. (2009) suggest pursuing a balanced strategy, creating the right incentives, building the capacity of private enterprises and strengthening the supporting market institutions including the venture capital system. Similar to their suggestions, a key reform recommendation given by the World Bank (2012) on China’s innovation policy is to redefine the government’s role in the national innovation system, “shifting away from targeted attempts at developing specific new technologies and moving toward institutional development and an enabling environment that supports economy-wide innovation efforts within a competitive market system.”

After three decades of economic reform, China has been moving toward establishing a market-based economy. Competition is strong in many though not all industries. The economic behavior of enterprises has become increasingly responsive to market forces as a result of competition, the growth of non-state enterprises, and management reforms within SOEs. The main tasks remaining are to develop legal, financial, and other institutions including the functions of the government necessary to the working of a market-based economy; convert SOEs including those with monopolies into modern commercial entities; improve corporate governance; and upgrade China’s economic structure where more innovative firms can flourish.

In a mature market economy, there exist a number of institutions that facilitate its functioning. The crucial factors are as follows: institutions which protect private property rights; a fair, level playing field for competition in both product and factor markets; fewer barriers to entry or exit. The essential step in China’s SOE reform is to create a market environment in which enterprises with all kinds of ownership arrangements can compete with each other under a fair environment and in which “the fittest survives.” To do so, a few questions need to be further addressed.

The ongoing economic reform has introduced and allowed free-market forces to function in China albeit on a gradual and trial basis. However, as development economics indicates, the market alone cannot solve all the problems; market and state are both necessary factors for coordinating economic activity and promoting a country’s development (Hayami 2001; Otsuka and Kalirajan 2006). Market failures in the supply of public goods can also occur in the case of private goods. The key question for a country’s development is how to arrive at an optimal combination of the roles of market and state in promoting a country’s welfare (Otsuka and Kalirajan 2006). The contribution of markets toward improving economic welfare will gradually be increased in response to the new opportunities opened up by the introduction of new technologies. The key process in technological change is described by Schumpeter as the introduction of innovation through the process of “creative destruction.” What drives entrepreneurs to undertake innovation is nothing but profit motives shaped by free-market forces (Schumpeter 1975).

In the case of China, the ongoing economic reform has been a process of interactions between the market and state, plus the fostering of entrepreneurship in China. The Chinese government has been trying to progress in this direction by promoting market economy in China while adjusting the role of government in the process of economic development. However, in many aspects, state interventions or personal disposition instead of market forces still play a major role in China’s economy, causing inefficient allocation of resources. Wu and Fan noticed that corruption is holding China back (see Chapter 4 in this volume) and some “special interest groups” in China are resistant to reform.5

The past experience of reform shows that the development of the Chinese economy has been to some extent accompanied by a process of “creative destruction,” as Joseph Schumpeter long ago labeled it. The improved environment since the economic reform in 1978 has nurtured private entrepreneurship in China. Entrepreneurial opportunities emerged from market development as well as from changing institutional rules in China. During the first stage of reform, a popular but transient behavior of entrepreneurs was the practice of taking advantage of gaps in both markets and institutional structures. As a result, informal processes that could lead to corruption are still rampant in China.

Ahmad and Hoffman (2008) suggested a framework for addressing and measuring entrepreneurship, in which six themes (regulatory framework, market conditions, access to capital, access to R&D and technology, entrepreneurial capabilities, and culture) were described as the major determinants affecting entrepreneurial performance. These determinant indicators are all important for the development of entrepreneurship in a country. It implies that if China wants to further promote its economic development it must hold onto the market-oriented economy with an adaptable regulatory framework, provide fair access for both SOEs and non-SOEs to capital and technology, and enhance a social culture to respect entrepreneurship and to increase entrepreneurial capabilities.

Since 2002, there has been a hot debate on whether China’s state-owned economy expands while its private economy shrinks. Some Chinese economists call this phenomenon “the advancement of the state and the retreat of the non-state,” and believe it has led to unintended but foreseeable social consequences that have weakened the momentum of the growing economy. If we look at the Figures 12.5–12.8, however, we find that in general the importance of the state sector in China has been shrinking but the non-state sector has been growing over time. For example, the proportion of state-owned industrial output was about 40 percent in 2002, but dropped to 26.2 percent in 2011, indicating that overall economic development is moving toward privatization. However, if we look more closely at the data in the China Statistics Yearbook, we find that the proportions of state-owned economy in oil and natural gas, tobacco, and non-ferrous metals industries have been increasing over recent years. A survey done by the Chinese Entrepreneurs indicates that the top industries with high domination of state-owned economy are oil, petrochemicals, aviation, steel, coal, finance, telecommunications, and railways. These industries are highly related to people’s livelihood and they are profitable monopoly industries in China. The Australian reported that “the 150,000 Chinese SOEs receive more than three-quarters of all formal bank loans, with the 4.5 million domestic firms receiving less than 10 percent. In 2009, the three largest Chinese SOEs earned more revenue than the largest 500 domestic private sector firms combined.”6

Experiences of many countries strongly suggest that the contribution of SOEs to overall economic performance is likely to be greatest when they are confined to natural monopolies or other industries where extensive public ownership is clearly needed on economic or compelling social grounds (OECD 2000). Although China is still a developing economy, defining the strategic industries where SOEs will dominate fairly narrowly is likely to be most conducive to economic growth and development. In particular, the economic gains from SOE reorganization could be greater if the current policies were directed at a more rapid and broader withdrawal of SOE monopolies from competitive industries, including its service sectors, and a wider and deeper participation of private capital in the restructuring of the SOE sector. With the high concentration of social resources and funds, SOE monopolies are getting larger and larger and becoming less and less energetic due to a long-term monopoly operation. Large SOE monopolies have created a drag on the economy through price distortion and vast opportunity for corruption and waste, leading to higher cost for consumers and a more unequal distribution of income.

In 2005 and 2010, the State Council respectively issued policies to encourage the non-state economy and to guide private investment flowing into these monopolized industries. However, in reality, there are still many visible and invisible barriers for private investment to flow into monopolized industries in China. Earlier in 2012, China’s Premier, Wen Jiabao, promised to push forward the reform of state monopolies: “We must move ahead with reform of the railway, power and other monopolized industries, complete and implement policies and measures aimed at promoting the development of the non-state economy, break monopolies and lower industry thresholds for new entrants.”7 In order to give a more important role to private investment by breaking up the monopolized industries, private business should be promoted with more accessible bank loans and other financial resources, such as equity markets, and should be allowed to invest in more high-end areas, such as finance and telecommunications.

Since the economic reform in 1978, the Chinese banking system has gradually evolved from a government-owned and centrally planned loan provider toward an increasingly competitive market in which different types of banks compete to provide a variety of financial services. One of the main purposes of the Chinese banking system reform has been to create incentives for its banks to behave more like competitive and commercial entities. Nonetheless, China’s banks have not been granted full autonomy, and are still heavily controlled and influenced by the government. Since banking reform is dealt with in Chapter 15 is this volume, the discussion here will deal only briefly with the relationship of banking reform to state enterprise reform.

There are two distinctive features of China’s banking system, which have important implications for the development of the enterprise sectors in China. First, China’s banking sector itself is still highly dominated by state-owned and state share-holding banks, although entry of new private institutions is encouraged in principle. The second distinctive feature is the concentration of financing on SOEs. SOEs have been traditionally favored by banks for loans, as SOEs are perceived to be lower risk or at least backed by the government in the event of loan forfeiture. Although the share has declined somewhat in recent years, SOEs still dominate the majority of bank loans in China, accounting for about 75 percent of total bank loans.8 Since the Chinese government initiated its economic stimulus policy after the global financial crisis in late 2008, there have been some signs showing that more shares of bank loans go to the state-owned or state-dominated sector. In 2009 alone, 85 percent of the newly added bank loans were granted to SOEs.9 The World Bank (2012) reported that the majority of the economic stimulus plan issued by the Chinese government went to the construction and infrastructure sector, which were still dominated by SOEs. SOEs also enjoy lower interest rates and preferential access to equity and bond market financing (Martin 2012). In contrast, non-state enterprises receive only a small fraction of commercial bank lending (World Bank 2012). Not surprisingly, non-state enterprises, with the exception of foreign-funded businesses, rely noticeably more on internal funds to finance their investment than do the SOEs.

Development of China’s banking system is therefore essential to the success of reforms to the enterprise sector. A key challenge to the current banking system that now disproportionately focuses on SOEs is to better serve the needs of the growing non-state sectors. Non-state enterprises are in general more efficient than SOEs in terms of total gross output value, employment, taxation and profits and more importantly productivity. Nonetheless, they are in a disadvantageous position to obtain financial support from banks. Therefore, the government needs to take steps to standardize the treatment of private capital in the banking sector, and banks need to make their lending process more transparent and fair so that small and medium-sized private enterprises have an equal means to finance their business and compete with SOEs. However, efforts to improve their financing are focused on adapting existing facilities but have met with limited success so far.

With more than twenty years’ development of equity markets in China since the 1990s, China’s stock markets have played an important role in the development of the Chinese economy and its market system. The stock markets have not only helped Chinese companies to raise the much-needed financial capital, but also helped to improve the corporate governance of listed companies. On the two national stock exchanges there were 2,342 firms listed by the end of 2011 and the overall stock market capitalization reached about two-thirds of China’s GDP.10 However, nearly all the listed firms are large SOEs, and the development of China’s equity markets is far from satisfactory.

The development of China’s stock markets has been hampered by excessive government control, segmented market structure, insufficient liquidity, lack of transparency, and an underdeveloped legal and regulatory framework. The inefficient performance of equity markets in China is due to the absence of a trading platform based on fairness and transparency, effective price-setting mechanisms driven by market forces, and a compensation mechanism designed to protect investors’ interests and especially the interests of small investors. With regard to financing in equity markets, there is tremendous bias in favor of SOEs over non-SOEs (Zhang 2005). This is in contrast with the increasing importance of non-state-owned firms in the Chinese economy since the 1990s. One may question to what extent China’s stock market performance is due to the fact that some listed companies sold junk shares at high prices; the interests of the investors were not duly protected and the market lacked credibility. In 2011, 252 companies raised IPO, but 55 of them, or 21.8 percent, had a decreased net profit in their first three-quarters. More recently, however, the authorities have been accelerating efforts to develop and better regulate the stock markets. The major motivation behind these efforts is twofold: to broaden and augment financing sources for SOEs; and to strengthen external financial discipline and the corporate governance of large SOEs.

Enterprise reform in China has been accompanied by the reform of China’s legal system because economic growth requires legal institutions put in place to offer stable and predictable rights of property and contract (North 1990; Hall and Jones 1999; and Clarke 2003). In the transition from “planned economy” to “a market economy,” China’s SOEs need to operate independently of the government and deal with other legal entities through market transactions. For private sector development, an independent, transparent, and enforceable legal system can offer guarantees to private property rights, facilitate business transactions, and build confidence among the entrepreneurs for reinvestment. With the ongoing and deepening economic reform, it is necessary for China to improve its legal system to meet the needs of further economic development and enterprise reform. Because Chapter 16 in this volume deals with legal reform, the discussion here will only summarize briefly the relevance of legal reform to enterprise reform.

To create a legal environment in which all enterprises – including both SOEs and non-SOEs – participate as independent market players, namely free of government interventions, reform is needed in the following legal areas: first, enterprise and labor contract laws need to be further strengthened, which define enterprises’ rights and obligations, regulate enterprises’ establishment and operation, and protect the legal rights of labor; second, contract law needs to be further improved to protect the legal rights of contracting parties and allow economic transactions between parties to replace administrative controls; third, bankruptcy and competition laws (anti-monopoly) need to be fully implemented to promote fair and effective competition among all kinds of enterprises and to ensure the continued protection of the public interest even without direct state management of enterprises; finally, China needs to strengthen its financial laws, including securities laws and regulations, to allow enterprise financing activities to take place in a market-driven environment rather than through a planning mechanism or being influenced by the governments. Through more than three decades’ efforts, China has made great improvements in its legal framework. Various laws and regulations mentioned above have been promulgated, implemented, and revised according to the needs of economic development. However, much more work needs to be done to improve the legal system and practice.

Among all these laws and regulations, the Corporate Law and the Labor Contract Law have played a significant role in enterprise reform and attracted a great deal of attention from the public. The Corporate Law of 1993 was important in protecting the interests of both corporations and shareholders by clearly defining the formation of corporations, corporate governance structure, corporate finance, shareholders’ rights, and so on. However, the majority of the existing SOEs were still essentially governed by the State Enterprise Act of 1988 and its subordinate regulations of 1992. To a great extent, the State Enterprise Act of 1988 was still influenced by the planned economy, while the Corporate Law of 1993 was the product of adopting a market economy in China. The Corporate Law of 1993 provided the solid legal foundations for the SOEs to be transformed into corporations and shareholding corporations. Meanwhile, through the economic and legal reforms, many relevant laws, including bankruptcy law, securities law and competition law, have also been promulgated and updated. The legal regime governing business organization was substantially revised in the middle of the first decade of the twenty-first century, so as to further support economic reform in China.

Another important legal update is the formation and development of the Labor Contract Law, aiming at the protection of labor rights. With the ongoing economic reform, industrial relationships have inevitably experienced fundamental changes, and labor legislation became necessary in the process of reform. The labor contract system was first experimented with in joint ventures in the Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in the 1980s and later extended to applying in SOEs. The Labor Law of 1995 was the first national law to introduce a labor contract system to break the “iron rice bowl” (permanent employment) in China. However, the Labor Law of 1995 did not provide adequate protection for employees. Employee abuse was rampant in China and labor–employer relations were precarious without the legal protection of labor rights. Labor disputes in China increased more than thirteen-fold between 1995 and 2006 (Ngok 2008). The continued privatization of SOEs has led to an increasing unemployment rate, especially among the poorly paid migrant workers since the late 1990s. The Labor Contract Law was passed in 2007 and came into effect in 2008 with the hope of filling some gaps left open by the Labor Law of 1995. It was designed to give employees greater rights and easier enforcement of their rights so as to achieve the ultimate social policy of creating and sustaining a “harmonious society.”

The rising wage rate resulting from demographic, statutory, and economic developments has put increasing pressures on enterprises in China, including both domestic and foreign-funded ones. China now is facing “the Lewis turning point” with reduced supply of surplus labor from rural to urban areas (Cai and Wang 2009). It has a significant impact on the structural changes in the Chinese economy as it will be more and more difficult for China to achieve extraordinary productivity growth while keeping inflation under control under the influence of this demographic change (Garnaut 2010). China’s enterprises will be compelled to grow based more on the improvement of productivity rather than the input of labor. To manage the change, the labor force needs to be provided with more training in service sectors and high-end manufacturing.

The global financial and economic crisis has reduced the demand for Chinese exports substantially. Many Chinese export-oriented enterprises went bankrupt, and millions of jobs were lost during the crisis period of 2008–9. To mitigate the negative impact caused by the international financial crisis, the Chinese government used various measures to promote its economy, such as increasing government investment, expanding domestic demand, encouraging indigenous innovation, and upgrading its economic structure. However, some of these measures may take a long time to be effective. The key is that China could still have room for further growth created by deepening its institutional reform. China should promote employment by opening up and developing the service sector. The service sector has a great potential to absorb the workers released from the export sector. To boost investments in the service sector, the Chinese government should first break up the monopolies of SOEs in such fields as finance, insurance, education, medical care, telecommunications, and transport – and open up these activities to private investment.

Further development of Chinese enterprises and their ambitions to become multinational companies have motivated them to invest overseas. The relatively limited domestic natural resource supplies and the fear of resource constraints on growth have motivated the Chinese government to encourage its SOEs and domestic private firms to invest overseas. China’s outward direct investment (ODI) has increased rapidly in recent years. By the end of 2009, China’s 108 central government-owned SOEs had invested in 5,901 foreign firms (SOASAC 2010). The total overseas assets belonging to central government-owned SOEs exceeded renminbi 4,000 billion (equivalent to US$ 597 billion using the 2009 exchange rate). In 2009, the profits received from overseas operations accounted for 37.7 percent of the total profits of central government-owned SOEs. According to the Ministry of Commerce, ODI from China’s SOEs accounted for 69.2 percent of total ODI stock by the end of 2009, whereas that from private firms only accounted for 1 percent of total ODI stock.11 All the top thirty firms ranked by size of overseas assets and firm size are SOEs.

Song et al. (2011) linked the participation of SOEs in overseas markets with domestic structural reform and firm development, as they are forced to navigate a new business and political or institutional environment in which privileges enjoyed in China are no longer available. The heightened competition abroad forces SOEs to increase their competitiveness through efficiency-enhancing measures. Therefore, for them, changes must occur in three fundamental areas of reform: competition, ownership, and regulation. The changes in these areas are crucial for the success of SOEs’ investment abroad and will have some impact on China’s reform agenda for the state sector in the future.

There has been a remarkable transformation in China’s enterprise sectors over the past three decades (1980–2010). In 1978, there were no Chinese mainland companies in the Fortune Global 500 list – in 2012 there were seventy, among which sixty-five were SOEs; China has made great achievements in enterprise reform and economic development. The non-SOE sector, especially domestic private enterprises, has become the largest share of output. Enterprise reform in China is shaped by several distinctive characteristics, reflecting policy-imposed constraints and other special characteristics of the economy, that need to be taken into account in drawing conclusions about the process.

Measures to be taken in the future should help boost enterprise financial performance and provide a further impetus to real growth in the economy as a whole. In many areas, reforms undertaken so far provide necessary institutional frameworks and mechanisms for improving enterprise performances, but the conditions required for their effective functioning are often lacking. Lack of adequate progress in some areas, such as the end of policy lending by commercial banks, is limiting or preventing progress in other areas. Nonetheless, several conclusions seem reasonable based on the evidence cited in this chapter.

First, non-state enterprises have become the main contributors to overall growth in output and employment in the economy in the past three decades and they are likely to remain the key player in determining the economy’s performance in the future. Reforming the SOE sector is essential to improving its efficiency and to releasing more resources for use in those more productive areas involving private businesses. But the extent to which these reforms result in improved performance of the economy as a whole depends on the degree to which the problems of the non-state sectors are alleviated, and their operational environments are improved.

Second, measures to reduce unfavorable conditions in financing the private sector have the potential to significantly improve financial performances of the commercial banks and other lending institutions as well as boosting the development of non-state enterprises. Further development of money and capital markets is important to ensure that financial discipline becomes firmly rooted. These markets are also needed to provide mechanisms for market-based enterprise restructuring, which is much required in China. In that process of enterprise restructuring, those inefficient enterprises whether SOEs or non-SOEs should be allowed to go bankrupt in order to free up the resources to be directed to those enterprises that are more efficient and productive. This is the only effective way for China to move toward optimizing its industrial structure and through this, its welfare improvement.

Third, the success of SOE reform depends on the creation of an egalitarian competitive environment, supported by more transparent and well-functioning institutions including China’s legal system. There need to be fundamental improvements in corporate governance of SOEs, in parallel with direct efforts to bolster the financial performance of enterprise. Many of the current financial problems of enterprises reflect past mistakes in investment and other business decisions arising from weaknesses in management and in financial discipline. Enterprises will need to respond more effectively to market forces than they often have in the past. The reforms need to make substantial progress in the above key areas in order for China’s enterprises to contribute more positively to future growth. This urgency partly reflects the fact that reforms have become increasingly interdependent, as well as the need for rapid and effective adjustments by enterprises to the changes in both the internal and external business environments that will come with growing domestic as well as international competition.

Finally, China is facing enormous challenges in the next phase of its growth and development. Deepening its enterprise system reform involving both the state and the non-state sector is an important part of China’s overall strategy. The success will depend on how China tackles the problems associated with the existing institutions and policies in relation to the future development of its state and non-state enterprises.

1 Able research assistance provided by Haiyang Zhang is gratefully acknowledged. All remaining possible errors are mine.

2 See China Statistics Yearbook in 1996 and 2003.

3 See “Message from Chairman and CEO” at <http://www.tsmc.com/english/csr/message_from_chairman.htm>, accessed on 18 December 2012.

4 See “Corporate Social Responsibility in China: Outlook and Challenges” at <http://www.triplepundit.com/2012/09/corporate-social-responsibility-in-china/>, accessed on 18 December 2012.

5 See “Special groups obtaining vested interests through power are reluctant to reform” by Jinglian Wu at <http://business.sohu.com/20121218/n360730175.shtml>, accessed on 20 December 2012 (in Chinese).

6 See “Retreat of private sector a millstone for Beijing’s next leaders”, by John Lee, The Australian, at <http://www.theaustralian.com.au/opinion/world-commentary/retreat-of-private-sector-a-millstone-for-beijings-next-leaders/story-e6frg6ux-1226509440039>, accessed on 27 November 2012.

7 See “Special Report: China’s other power struggle”, by Reuters, at <http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/10/16/us-china-soe-idUSBRE89F1MP20121016>, accessed on 27 November 2012.

8 See “Economy of the People’s Republic of China”, Wikipedia, <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_the_People’s_Republic_of_China>, accessed on 15 January 2013.

9 See “SOEs Are Important, But Let’s Not Exaggerate”, China Economic Watch, <http://www.piie.com/blogs/china/?p=776>, accessed on 15 January 2013.

10 See “Listed Domestic Companies Total in China”, at Trading Economics <http://www.tradingeconomics.com/china/listed-domestic-companies-total-wb-data.html>, accessed on 15 January. 2013.

11 See Statistics Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment published by the Ministry of Commerce of China, 2009.

Ahmad, N. and Hoffman, A. (2008) ‘A Framework for Addressing and Measuring Entrepreneurship’, OECD Statistics Working Papers 2008/02, OECD Publishing http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/243160627270.

Arrow, K. (2001) ‘The Role of Time’, chapter 6 in L. R. Klein and M. Pomer (eds.), The New Russia: Transition Gone Awry, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 85–91.

Ayyagari, M., Kunt, A. D., and Maksimovic, V. (2010) ‘Formal versus Informal Finance: Evidence from China’, published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Financial Studies.