Chapter 1

Primitive Fire and Cordage

The learning of the necessary “skills” to live directly with nature, eliminating the need of intermediaries, isn’t really all that difficult. You learn a little about this aspect…a bit about that one…and then another. Pretty soon you find that most of them overlap and the further you get along in your natural education, the easier it is to learn.

Many years ago when I first got serious about putting all this together (my first step was to get rid of the TV, and then electricity), I felt that if I were to learn a few of the basic primitive “survival” skills, I’d really become quite the woodsman. I soon found that the more that I learned, the more I still had to learn. I read (and I urge anyone interested in learning to also read) everything that I could lay my hands on that deals with living with nature. There’s a lot written on all aspects of it—some poor, some superb, but most lying somewhere in the middle.

Before you can decide what’s workable, you’ll have to get out and work with it. Reading only goes so far. When you actually begin to put into practice what you’re reading, then it becomes obvious just who knows what he or she is writing about.

No special talent is needed here—only the ability to follow a bunch of natural rules (physics). Any of the primitive skills, today as well as yesterday, can be carried to the extreme and become an art. I’m far from being expert in woodsmanship. I have, though, taught myself what I need to know to go “naked into the wilderness” and not only survive but before long be living fairly comfortably (unless, of course, I froze to death first). I refer to my teachings as primitive “living” skills, not “survival” skills, though they can be used in that concept. I have taught myself to be proficient in these skills—not to be an artist.

Since 1987 I’ve made thousands of fires with the bow and drill and with the hand-drill methods. So I’m proficient enough in this to teach it to others. The same holds true with the making of cordage. The more you learn, the more you realize what there is to learn—but the easier it becomes to learn it.

Bow Drill and Hand Drill

The basic principle of making fire with either a bow or a hand drill is really very simple. The amount of practice needed to develop that special touch which enables you to regularly succeed in this is another thing entirely.

To say “make fire” with the bow or hand drill is really a misnomer. Actually, what’s accomplished is that the wooden drill spinning on another piece of wood creates friction, which creates dust, and eventually things get hot enough that a spark is created. The compressed pile of dust that has been formed becomes like the hot tip of a cigarette that’s placed into a pile of tinder and coaxed into a flame.

Simple? Yeh, really it is. I’ve had students “make fire” within minutes of being exposed to this procedure, and understand just what they were doing.

I’ll first show you how to make fire (bow drill first, and hand drill a little later). I’ll quickly describe the necessary components and the steps to follow. Then we’ll get down to brass tacks and go through it again, dwelling a bit more on how to assemble the parts and to put it all together. When you finish with this, you’ll be able to make fire.

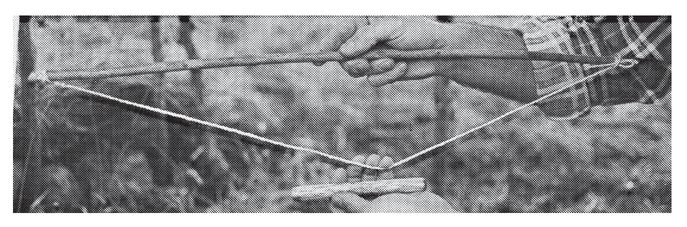

We have five components: (1) the bow, a limber stick about 30” long; (2) the drill and (3) the fireboard, both of which are softwoods; (4) a cup, called a “bearing block,” in which the upper end of the drill is placed to keep it from drilling through the palm of your hand; and finally (5) the bowstring, which will be covered in greater detail later in this book.

Simplified Directions for Making a Bow Drill

We take a knife and cut a notch and a slight depression into the fireboard, twist the drill into the string of the bow, place one end of the drill into the depression of the fireboard, place the bearing block on top of the drill, and spin the drill by pushing the bow back and forth till a spark is formed. We finish by dropping the spark into a prepared “bird’s nest” of tinder and gently blowing it into flame. Easy?…sure. And you might be able to make it work with no more information than this. Some 13 years ago, three of us spent the better part of a day wearing ourselves out with no more information than what you’ve just read—and eventually made fire.

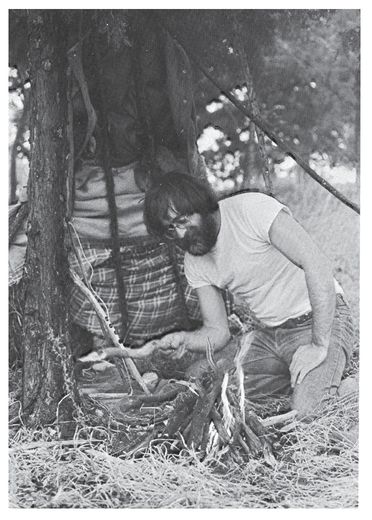

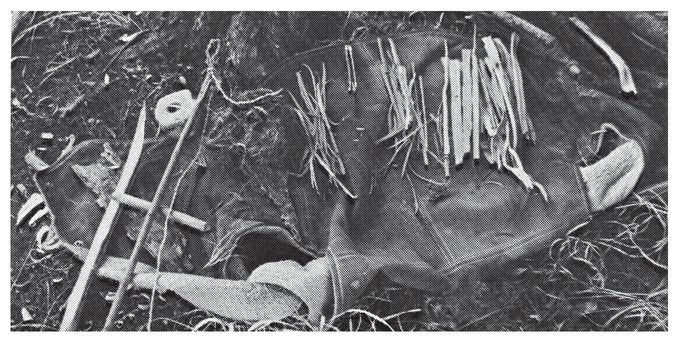

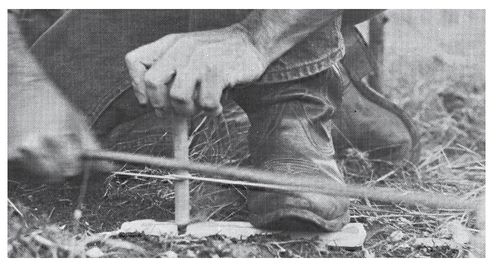

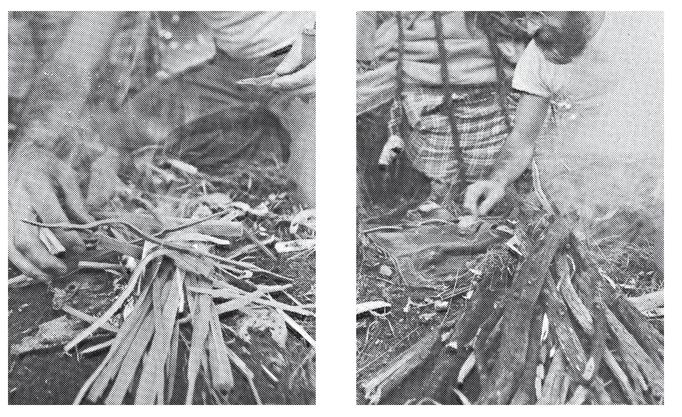

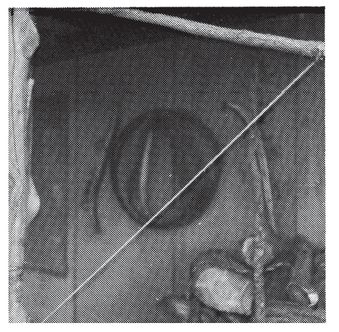

The day most of these photos were shot, the Fahrenheit temperature was in the 40s and it was misting. I threw up the crude shelter using only what one would normally have: two light jackets and a shirt, using also rocks and grass. The purpose of the shelter was just to block the wind and rain from preventing my making of fire.

Parts of a Bow Drill

Now I’ll go into more detail about all the parts—the whats and the whys, how to gather the parts, and how to fashion them under primitive conditions. The special touch you’ll have to develop yourself through practice (it does come pretty easily).

BOW—This is the easiest part to obtain. A reasonably limber stick (limb or piece of brush), 1/2” to 3/4” thick, approximately 30” long. It needs to be limber enough to create just the right amount of tension on the string when the drill’s inserted. Too limber and you’ll have trouble with the string slipping on the drill. Too stiff and too much stress will be placed on the string and the drill, resulting in the drill’s continually flying out on you, and most often the string’s breaking. (Believe me, the stress created on the string and the drill is nothing compared to the stress that’ll be building in you at this point!) The length of about 30” is also important, though a bow of only a few inches, or even one of several feet, would work, just not as well. At that length the bow isn’t too cumbersome and will allow for a good, full sweep of the entire length. This is critically important, as every time the bow stops to change directions, everything cools off a tiny bit, thus impeding your efforts.

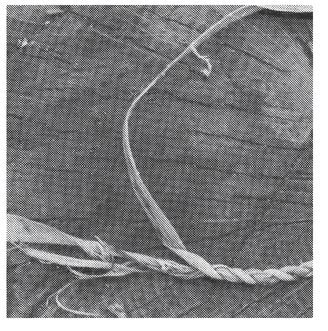

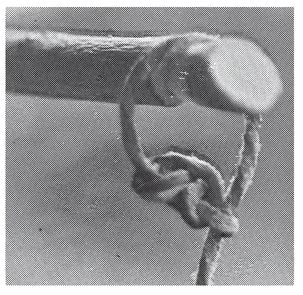

Raw squirrel skin cord “made fire” the first time. The hair rubbed off while in use; spark was found beneath pile of hair. Note thinness where skin’s about to break. Fortunately, I got the spark first (note coal) and also had plenty of extra length to reuse the skin after drying.

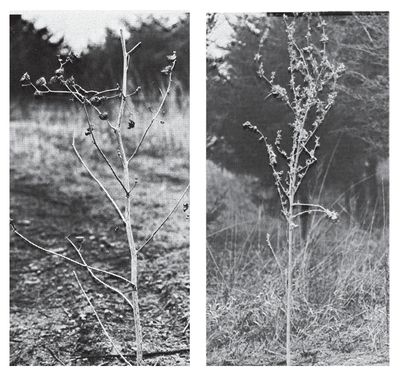

DRILL—We now need to be a bit more particular. A softwood is necessary. Also, dead and dry (I’ll mention damp wood later). Literally dozens of woods will work for a drill. Cottonwood, aspen, and yucca are my favorites, not only because they work well but also because they’re abundant in the parts of the country where I live and travel. Willow is a favorite among many firemakers. I’ve heard that sage works well too, as do box elder and hackberry. The smaller limbs and sapwood of cedar, locust, and ash would be fine (though the heartwoods of these are too hard). The list goes on. I’ve been told and have read to avoid resinous woods, such as pine. Cedar works, at least in some parts of the country. Experiment with what’s available to you. Members of the cottonwood family (including birch, aspen, and poplar) can be found in most parts of the country; all of them work superbly. Search out dead limbs, preferably off the ground (to eliminate absorption of ground moisture) and with bark weathered away. Check the condition of the wood by pressing it with your thumbnail. If it makes a slight indentation easily without crumbling, it should be about right. Also, if it breaks easily and cleanly with a snap, it has no greenness or moisture left in it. The drill needs to be about as small around as your little finger up to as big as your thumb. No real exactness here, though I wouldn’t go much for larger or smaller (since a smaller drill spins more with each pass of the bow, thereby creating friction faster but also drilling through the fireboard faster, sometimes before the spark has formed).

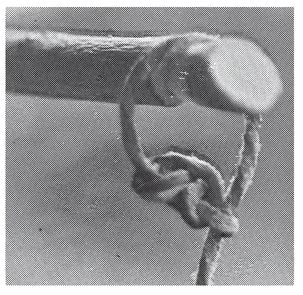

One end of the bow I tie permanently, usually with a slip knot.

The other end I tie with a single slip that can be untied easily and retightened as the string stretches. This is the end that I hold. This way, I can also hold any long loose end to prevent it from flying around and possibly knocking my dust pile all to hell.

The ideal length of the drill is 6” to 8”. Too long and it’s hard to manage, too short and your bow hand gets in the way of the drill and you can’t see what is happening. And straight, since if there’s a warp in the drill, it’ll wobble as it spins and create problems. Most times a slightly curved drill can be straightened with your knife.

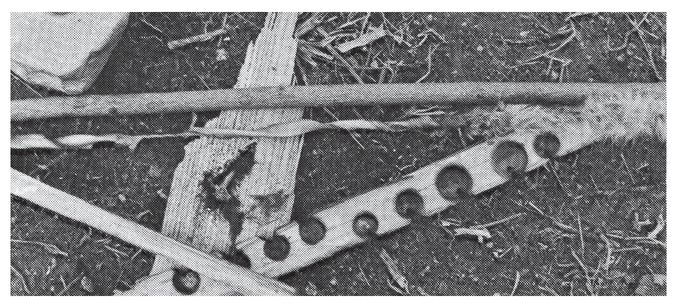

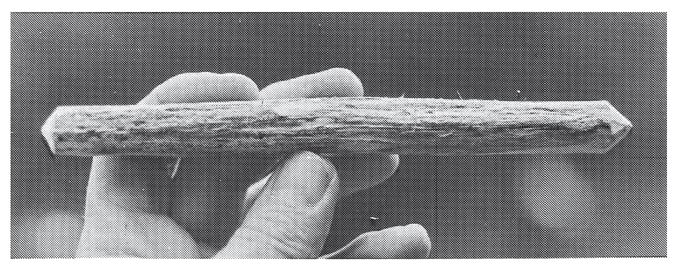

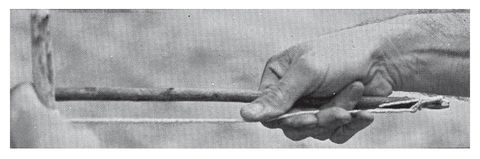

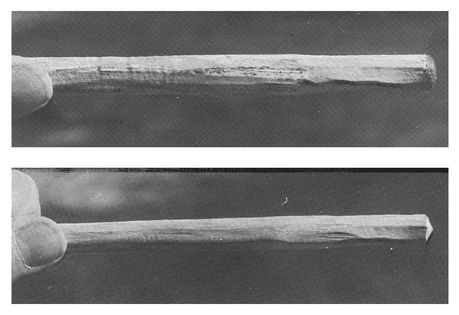

A fresh drill (here, yucca; my favorite combination is a yucca drill on a cottonwood fireboard). The right side is more pointed for the bearing block. The slight tit on the left helps it to stay where it belongs in the fireboard till the hole’s enlarged.

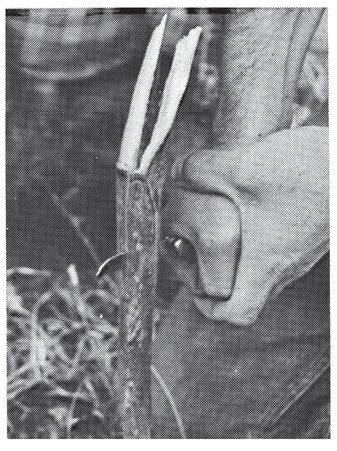

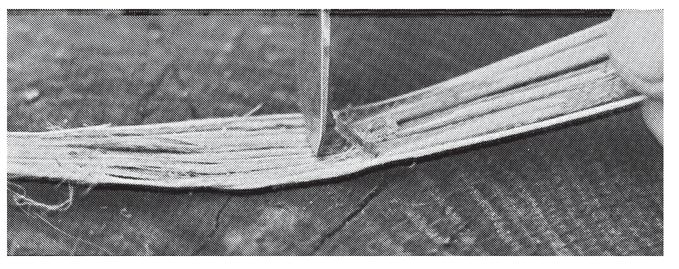

FIREBOARD—The fireboard can, but need not, be the same material as the drill. Usually, it will be. Again, it must be a softwood. Check its condition, which should be the same as for the drill. The size of the board is variable. It need only be larger in width than the diameter of the drill. I like to make mine from 1 1/2”to 2” wide (remember that nothing here is exact). Take the limb of your choosing and split it in half, using your knife. Shave the split side till the board will lie flat, shave down the round side till the board is about 1/2” thick, and then square up the sides.

BEARING BLOCK—This is a very simple piece, and an important one, but one not all that easy to come up with in a survival situation. For at-home work, I suggest a 1 oz. shot glass, which fits the hand comfortably, has a hole of the right size for the drill, and has a surface as smooth as you’ll find (with the goal of eliminating friction). You can also find a semisoft rock and drill a 1/2” to 3/4” hole in it about 1/2” deep, then lubricate it up with Crisco (“bear grease in a can”). You need to eliminate the friction at this end. (I have in the past used various knots of hardwoods. Some of them, though, had soft spots in them and I was coming up with smoke from my palm before the fireboard!) I carry with and use at home, in demonstrations, and in base camps a rock about 3” x 2 1/2” x 1 1/2” thick with a dandy hole in it, though it’s pretty hefty to carry around in the timber. For now, this is all you need to know. We’ll go into obtaining this under primitive conditions a bit later.

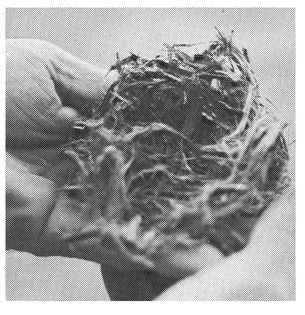

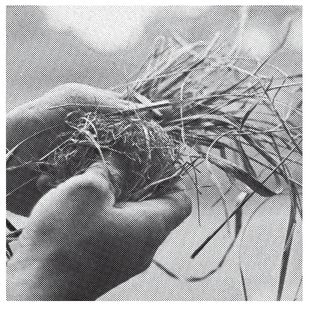

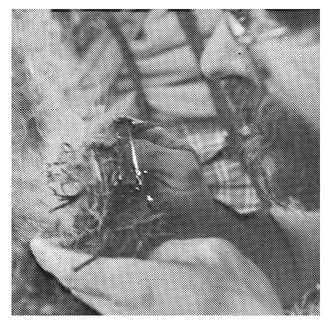

Since there’s a definite satisfaction in taking your first ever-spark created with the bow drill and blowing it into flame, let’s have you gather up and prepare some tinder at this time. Let’s make up a batch. I really like the dry inner bark of cedar (cottonwood is good, also), plus some dry, fine grasses. Roll these around in your hands till it’s fine as a cotton ball. You won’t need much; a small handful will be plenty. Form a hole in it like a bird’s nest. Place this on a piece of bark or cardboard (so that when it bursts into flame you won’t barbecue your hand).

Using Your Bow Drill

With the information contained thus far, you’re ready to “make fire.” We’ll run you through it once now. The information presented below is certainly useful (or I wouldn’t have gone to the trouble to write it), but it deals mostly with gathering the materials under primitive conditions.

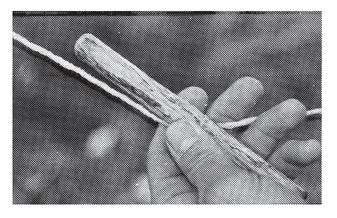

BOW—Archers, string your bow! Almost any cordage will work, but it should be strong and not too thin, as it will tend to break easily with the first-timer. Also, the heavier cordage (not rope) seems to get more of a grip on the drill. Here I’d suggest using a “rawhide” (not genuine rawhide) boot lace, which is about ideal. I twist mine tight, which seems to grab the drill that much better. In short order, you’ll begin to feel precisely the right amount of tension. The string will stretch considerably with use, especially at first, and adjustments will have to be made as you go along. The bow is not strung tight; considerable slack is left. When the drill is placed in the bow, the slack is taken up (note top photo on page 9). Remember, the tension must be just so; too tight is worse than only a little slack, but there isn’t much room for variables here.

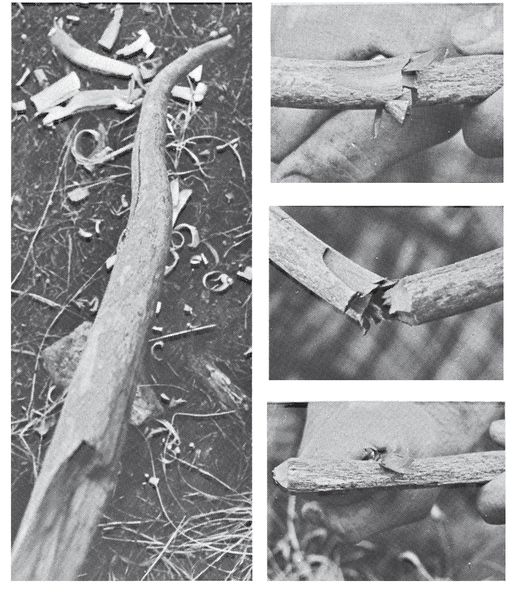

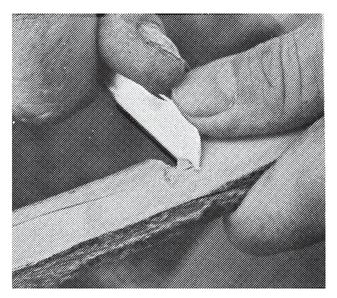

DRILL—Now let’s take our selected piece for the drill. I like to point the upper end a bit (the end that goes into the bearing block). When breaking in a new hole in the fireboard (as in this case), I find it easier to operate if I carve the working end into a slight “tit” (study photos on page 9). Doing this gives it a tendency to take a bit longer to mate the drill to the hole, but also assists in keeping the drill from kicking out of the fireboard while the depression enlarges to fit the drill. By the time the two mate, the hole and the drill fit better.

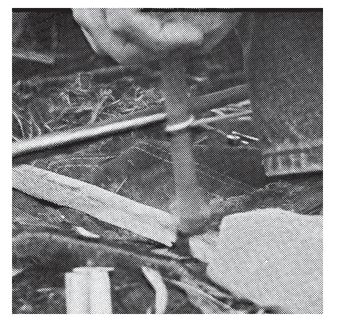

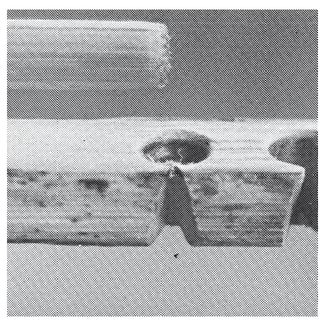

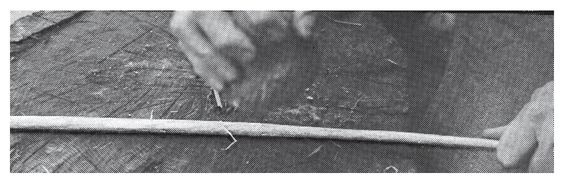

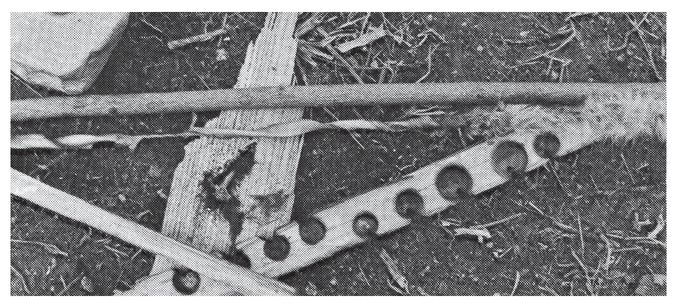

Splitting the fireboard.

Flattening and squaring the edges.

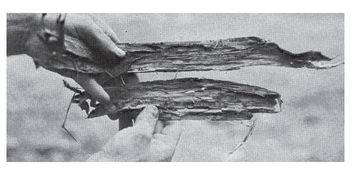

Cedar bark stripped from dead tree.

Shredded between fingers (or rolled between palms) to loosen and separate fibers.

Bird’s nest of cedar.

Same of grasses.

Bow (in this case a piece of dogwood) strung with deer rawhide. I always string the drill the same way, resulting in the top of the drill being up and the drill ending up on the outside of the string, thereby staying out of the way of the bow hand.

Stick selected for drill. I chose the straight middle portion.

Scoring around the stick first makes it easier to break where you want it to.

“Straightening” the drill by shaving it.

FIREBOARD—Now take hold of the piece prepared for this. There are two approaches to take here. I’ll talk you through one and mention the other. Both work.

With your knife, cut a “V” notch approximately 1/4” to 5/16” wide extending into the board almost half the diameter of the drill (see photo below). At the point of the “V” of this notch, dig out a slight depression for the end of the drill to fit into. (The other method is to dig your depression first and then, after the hole has been started with the drill, to cut the notch.) The depression must be in far enough so that when the hole is started, the notch retains enough material at the wide part of the “V” (at the edge of the board) to prevent the drill from kicking out. If the drill does kick out, breaking off this retainer (which helps to hold the drill), you may as well begin a new hole, as if you don’t you’ll encounter only frustration.

Cutting the notch.

Cutting the depression for the drill.

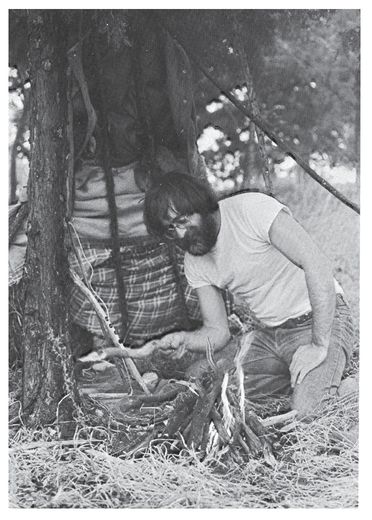

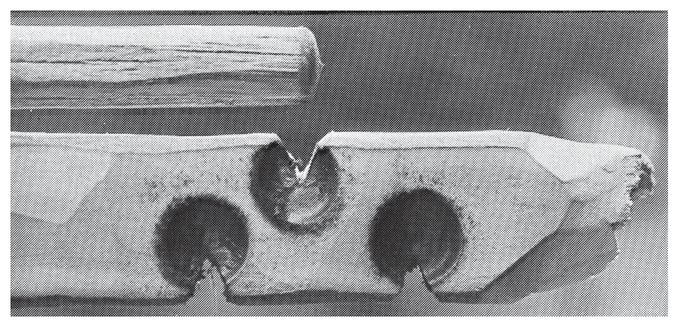

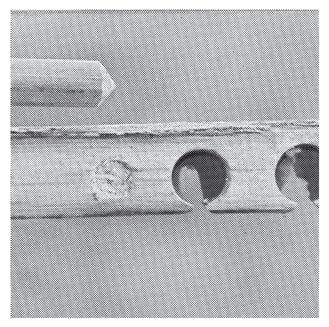

Notches almost halfway to center of drill hole.

Hole on the left is too close to the edge, so the drill will only fly out. When this happens, it’s best to start another. The hole on the right is great. “V” could even be a bit deeper, but this worked well.

Now, let’s get serious. Place a piece of bark (you nonprimitives can use cardboard) under the notch cut in the fireboard. This serves two purposes: (1) to catch the dust and spark, enabling you to drop it into the tinder, and (2) to act as insulation between the fireboard or dust and the ground, which may be damp, cool, or both, slowing down or preventing spark creation.

The following instructions are for a right-hander; you southpaws, just reverse the procedure. Get down on your right knee (see photo next page). Place the ball of your left foot on the fireboard, making certain that it’s secure and doesn’t rock. An unsteady board can result in the knocking of your dust pile all to hell. I like the notch to be about 2 1/2” to 3” out from the inside of my foot, which is where my hand automatically falls into place directly over the notch when my wrist is locked against my left calf. Wrap the drill in the string (as noted in photo) and place the proper end into the depression of the fireboard. Take the bearing block in your left hand, place it on top of the drill, and lock your left wrist securely against your left calf (this is important, as you want the hand holding the bearing block to be completely steady; if it sways to and fro while drilling, you’ll be inviting trouble). All that’s necessary now is to run the bow back and forth. At this point you’ll start developing the “feel” of what you’re doing.

The amount of downward pressure applied to the drill, combined with the speed of the bow, is what determines how much friction is created, thus how quickly a spark is formed. When you first begin, don’t even think “fire”—instead, concentrate only on becoming comfortable with the operation (kinda like chewing tobacco and walking at the same time). Make smooth, full strokes with the bow, running it the entire length of the string. Remember that every time you change directions, that split-second stop cools things off just a little. Keep the drill perpendicular.

The string has a tendency to wander either up or down the drill while spinning. Control this by pointing the end of the bow either slightly up or down, whichever seems to work. The pressure that you’re able to apply with your thumb and fingers of the bow hand on the string will also help.

Before you begin to “make fire,” have all ingredients at hand. From left: fireboard, drill, bearing block, strung bow, tinder, four piles of kindling in various sizes, and, at far right, larger wood—all laid out on my vest to keep them from absorbing ground moisture (the ground was wet).

Drill straight up and down, with left wrist locked securely against left calf.

Vary the amount of pressure on the drill. Begin with only a slight amount and increase it as you become more comfortable. Too much pressure, and things will want to bind up and the string to begin slipping on the drill. Whenever this happens, you must let up on your pressure, because no matter how fast the bow’s moving, if the drill isn’t spinning there’s no friction. If not enough pressure is applied, nothing will happen.

When beginning to mate a new drill to a new hole (what we’re doing here), there’ll be a certain amount of drilling where nothing seems to be happening. This can last from only several seconds to several minutes, depending on the type and the condition of the wood. At first the drill will spin smoothly, as if sliding on a freshly waxed floor. Then suddenly, as the drill and fireboard begin to “mate,” it will act as if you’ve gone from the waxed floor to sandpaper. This difference you feel, and hear.

Now, control and feel become all-important. The drill, which to this point was easy to control, suddenly becomes more difficult. You may find that you need to slightly tilt the wrist holding the bearing block ever so slightly one way and then the other as you run the bow back and forth, so as to keep the drill from kicking out of the hole.

Right after the two mate, and the first smoke and dust appear, I usually take a quick break before I go after the spark. This allows me to catch my breath and relax my muscles so that when I start up again I’m fresh. This often makes things a bit easier.

At this point, bear in mind that the hole isn’t yet deep enough to hold the drill on its own. It still will take some care on your part to keep it from kicking out. Now that the friction has begun, the drill is slightly more difficult to control. You’ll feel this, in short order. Vary the amount of downward pressure on the drill to coincide with the speed of the bow. You will develop the feel.

Here’s another very important tip. I had made fire this way for 11 years before stumbling onto this technique, and now I can’t imagine ever having made fire successfully, regularly, without having applied it. As mentioned before, the string will stretch while in use. A good, flexible bow will compensate for a lot of this, but eventually the string will become so loose that it slips on the drill when you apply the proper amount of pressure. Once, just as the spark was about ready, my string began slipping badly. Without thinking, I took the string between the first two fingers and the thumb of the bow hand and took up enough slack so that I was able to successfully finish. Now, anytime I take up the bow, the fingers and thumb just naturally wrap on the string (see photo below).

Note how I use my thumb and fingers to control string tension. Use whatever’s most comfortable for you.

If you concentrate on keeping the drill perpendicular—the left wrist locked tightly against the left calf, the bow taking long, smooth strokes, the fireboard steady and not wobbling—the spark will form of itself. First the smoke will begin, then dust will rise, then heavier smoke, and the dust will get blacker. Keep yourself relaxed and merely concentrate on the smoothness of the operation. There will be a spark.

Once the drill and hole mate, the spark will normally be created in less than 30 seconds. Once, timing myself, I had a spark in 10 seconds. If everything is working, it doesn’t take long.

When you have your spark (most of the time it’ll be hidden—the dust pile’s smoking is your sign), carefully lift away the drill and place it aside. There’s no big rush. I’ve left the smoldering dust for up to four minutes while I went in search of tinder, and still had a fine coal. Pick up the bark or cardboard holding the spark, fan it some with your hand, blow gently on it, let any slight breeze help (not a wind strong enough to blow it away, though). When it glows, drop it into your bird’s nest of tinder. Fold the tinder over the top and begin blowing the spark more and more as it gets hotter. Suddenly…fire!

Note black dust and smoke—a spark is there.

Dropping it into the “bird’s nest” of tinder.

Blowing tinder to flame.

Adding the first of the finest shavings of kindling.

Adding larger kindling and adding larger pieces of wood. On wet days, the inside of most woods will be dry. From spark to good solid fire (as in this series of photos) took less than a minute, but to get the spark took longer than usual because of wet weather and gusty winds.

When I first began making fire this way, I had the tendency to wear myself out by the time that the spark was formed. Someone else had to blow it into flame because I would just blow the whole damn thing away. No need for this. If you concentrate only on the control of the drill and the smooth operation of the bow, taking extra care to remind yourself to remain calm and relaxed, the spark will form on its own and you’ll be left fresh enough to easily blow the spark to flame. If you’re getting winded, you’re doing something wrong.

Many times it seems that no matter what you do, a spark simply won’t come into being. The chances of this happening seem to rise proportionately with the size of the crowd that you’re demonstrating this to. But when—not if—you do get that spark, whether it’s the first or the hundredth, cherish and glow with it. It’s something that I never take for granted. Like calling coyotes, there are so many things that can go wrong, yet each time it works I feel a real sense of accomplishment.

Some Observations on Using the Bow Drill

For the last few passes of the bow, some folks advise that you apply slightly less pressure on the drill, to kick out the spark that may be under it. I usually don’t find this necessary, but if unsure of the spark I sometimes do it.

If I seem to have difficulty getting a sure spark, I often make several furious passes with the bow at the last. I don’t like to do this, though, because it has the tendency to wind me. Then I lose control of the operation at this point and the drill kicks out, knocking away the dust pile.

Usually you can tell that the spark has formed, because you’ll see a wisp of smoke rising from the dust, separate from the smoke created by the drill.

On occasion, the entire pile of dust will suddenly glow—a good sign!

A single hole in the fireboard is capable of many sparks. Before using it again, it helps to slightly roughen the tip of the drill and the hole.

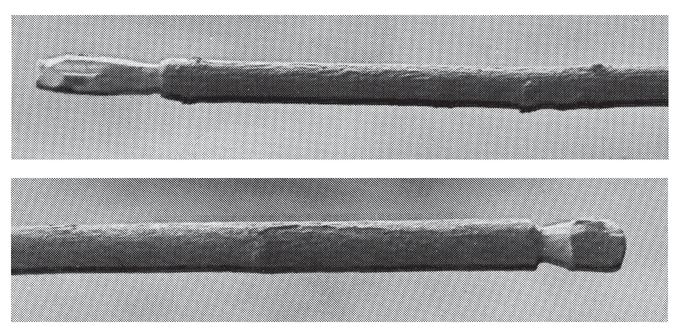

After several uses, especially with too tight a string, the drill will become too “round,” causing the string to slip. This is usually easily corrected by carefully shaving it till it’s once again unround.

Ear wax, or oil from your hair or the side of your nose, will help to eliminate friction in the bearing block. Always remember that you’re eliminating friction at the bearing block, and creating it at the fireboard.

Avoid placing the wrong end of the drill into the fireboard, as that little bit of oil can really foul things up.

Under damp conditions, find and use the driest woods available, and get into the driest location that you can to work. If the wood’s only damp, it can still work, but it will take a lot longer. The spinning drill eventually will dry things enough to work, though you’ll have a lot of strikes against you.

Under primitive conditions, the hardest components to gather will be the string (covered later) and the bearing block. Sometimes you’ll find a ready-made block in a stone with precisely the right depression, but don’t count on it. You might find a piece of bone that will work (say, from the skulls of small critters). Also look for a piece of hardwood, possibly containing a knot with a slight hole that you can easily enlarge. If you find something that might work, you can form or enlarge the hole by using the bow or drill. Use a hard piece of wood for the drill (or maybe you’ll be lucky enough to come up with a “natural” rock drill), definitely something harder than the block material. Ingenuity and common sense help a lot.

Hand Drill

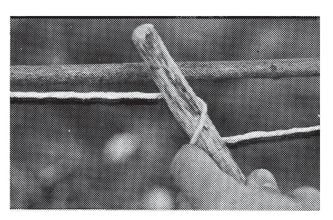

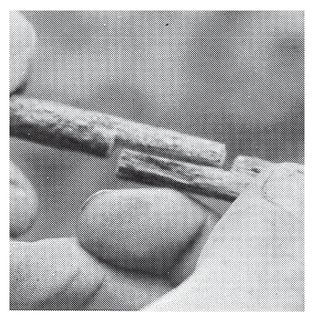

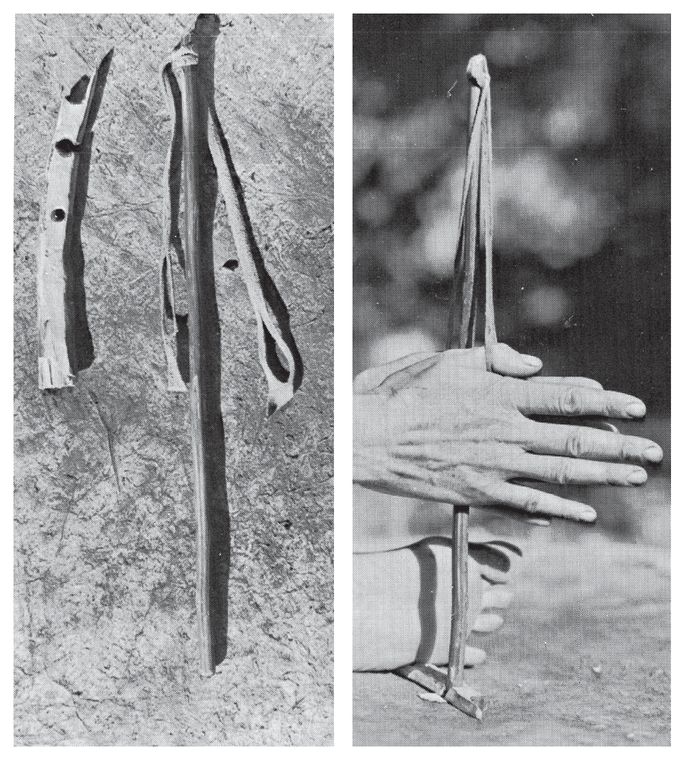

Note how cordage has “rounded” the drill.

The drill has been shaved “unround” and a tip formed for starting a new hole.

To now explain to you how to make fire with the hand drill will be simple—at least in theory. In practice, though, you’ll be faced with a much greater challenge than the bow or drill. The basic principle remains the same: to create friction with a wooden drill on a fireboard. The spinning of the drill, the fireboard, the notch, the dust, and the spark—all seem somewhat the same. But…

Parts of a Hand Drill

DRILL—The material for use here differs little from what we covered for the bow drill, except that because of the extra difficulty in creating friction here you need to be more choosy. The ideal length of a hand drill, for my length arms, is about 18” to 24”. I usually begin with a few inches longer, as this shortens quickly. Too long a drill and the top has a tendency to whip around, causing you to lose control (so much more important here). Too short, and you don’t get the full benefit of a long downward run of the hands before having to return to the top once again. I prefer a diameter of about 1/4”, to gain more revolutions of the drill for each sweep of the hands (a drill that’s too thin and limber will bend from the hands’ downward pressure).

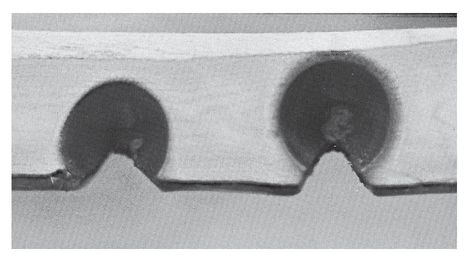

FIREBOARD—Again, the basic type is the same as for the bow or drill. I’d been having trouble catching a spark, when someone suggested a fireboard thinner than the one I’d been using. When I cut down the cottonwood board that I had been using to about 1/4” to 3/8”, things improved. With the softer yucca, I still keep the board about 1/2” thick. With the hand drill, I begin the depression and hole before I cut the notch. I also cut the notch slightly different than for the bow drill. I keep it closed at the top, flaring it open toward the bottom of the fireboard (note photos on page 20). I find that the drill has cut the hole below this point before things get hot enough to matter, and that the closed top then forces more of the hot dust into the notch, rather than letting it spill over the top.

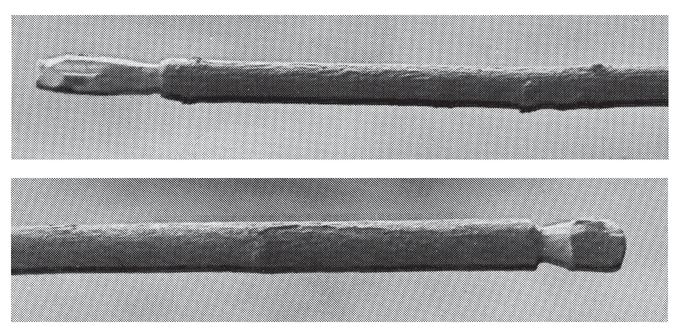

Note that the last 1 1/2” of this cattail hand drill was slightly shaved, to remove some but not all of the outer shell.

Using Your Hand Drill

To put this in action, get into a comfortable position. My left foot again holds the fireboard, but your position may not be the same. For me, it’s slightly different. I need to place the foot out a bit further and drop my knee out of the way somewhat, so that I can get a good full run of my hands down the length of the drill. I use the side of my heel to hold the board. Your hands must come down straight. You must keep the drill perpendicular. By placing my foot and knee slightly different than for the bow drill, I’m able to start my hands “rubbing” at the highest comfortable point (in my case, 24”) and to keep them going to a point about 6” above the fireboard. Once you reach the lowest point, raise your hands again to the top one at a time, so that you can keep constant downward pressure on the drill. If any air is allowed to reach under the drill, it cools everything off. Once both hands are up, repeat the procedure. Eventually the smoke, dust, and spark will appear—though not all that easily.

This procedure will wear you out, I assure you. A completely new set of muscles is at work here. After you’ve done this for 45 seconds or so, you’ll feel as if you’ve run the Boston Marathon, yet using your arms instead of your legs. It’s strenuous and it takes a lot of practice to get this operation down smoothly, which it must be to be successful. I suggest that you do a lot of practicing before you even think “fire.” This is a bit more complicated than chewing tobacco while walking. Here you must also juggle. It does take practice, not only to get everything running smoothly, but also to get yourself into some semblance of physical well-being. This does sap your energies. (Anyhow, it does mine.) It also creates blisters on the palm of your hands, which eventually will turn to calluses if worked at long enough. It took me well over a month of daily workouts to develop a good set of calluses, which a four-week vacation of “city living” took away.

Some Observations on Using the Hand Drill

When you first attempt making fire with a hand drill, I suggest going slow. Get the movements down to where everything runs smoothly and automatically. Your hands clasp the drill at the top, you rub the drill between your palms (keeping constant downward pressure), you keep the drill perpendicular at all times, when your hands reach the bottom you grasp the drill with the left hand’s thumb and forefinger, you raise the right hand to the top and hold the drill firmly while the left hand comes back up (thanks, Bob!), then repeat…repeat…and repeat. Over and over, slowly at first, and then speed up as it becomes more natural to you. Speed and downward pressure are all-important.

Fresh cattail hand drill tip and depression in fireboard.

The hole is begun. Note carefully how notch is cut. A cattail drill and a yucca fireboard are easy for the hand drill.

Spitting on your hands helps retain a little extra “grip” on the drill (thanks, Bryan!), allowing a few more spins before your hands reach bottom. Always put the thickest end of the drill down, as this kinda slows the hands’ trip downward also.

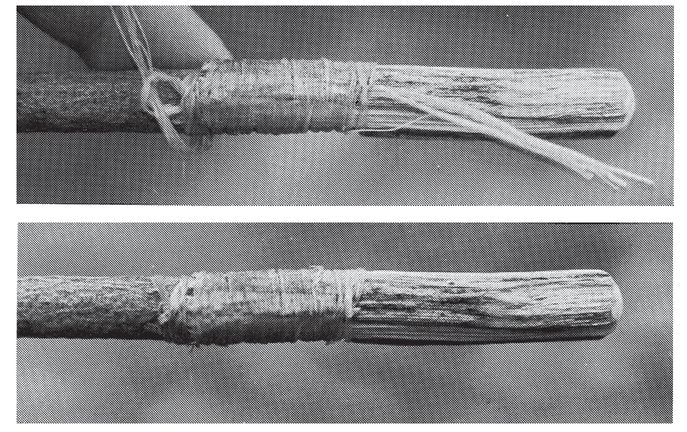

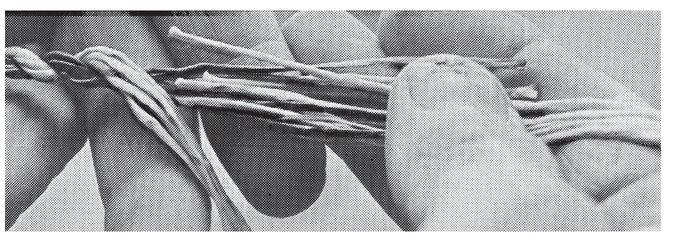

My most commonly used drills are stems of cattail or mullein (thanks, Dick!). Most of these stalks are just slightly bent, though. They must be straight, so be selective. I know of one woodsman who uses only willow. Since an ideal drill is sometimes difficult to find, a good idea is to make your drill beforehand out of whatever wood you like (I prefer the dogwood that I use for arrowshafts), then splice a tip of your choice for the working end (see photos opposite).

I find that the outer shell at the base of the cattail is just enough tougher than the inner portion that it tends to wear faster at the outer edges, leaving a hole that looks like an anthill. It won’t work this way. To compensate for this, most times I’ll find it necessary to slightly shave the outside. This takes practice to remove precisely the right amount. Further up the stem, I don’t find this problem.

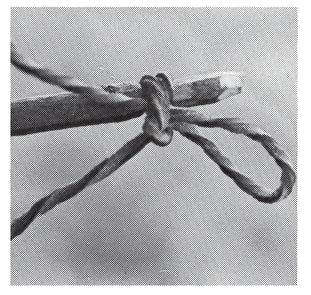

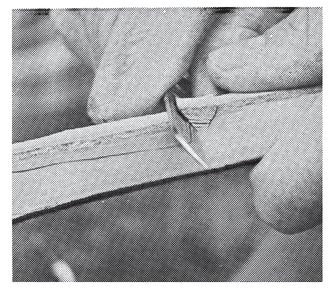

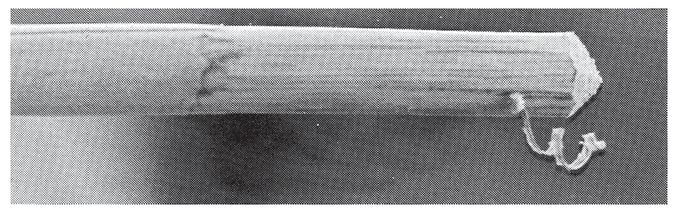

Hand drill spliced to receive a softer tip (here yucca). Splice wrapped with sinew, showing how to hide loose ends. Just pull the right-hand string and the noose will pull tight.

Spliced tip ready for service.

This is difficult for me to explain, and probably more difficult for many of you to understand, but before my first sparks arrived with the hand drill (they still don’t come with regularity) my mind and body became “one” with the drill and fireboard! You may or may not experience the same, but this has happened in all cases when I’ve successfully gotten a spark with the hand drill.

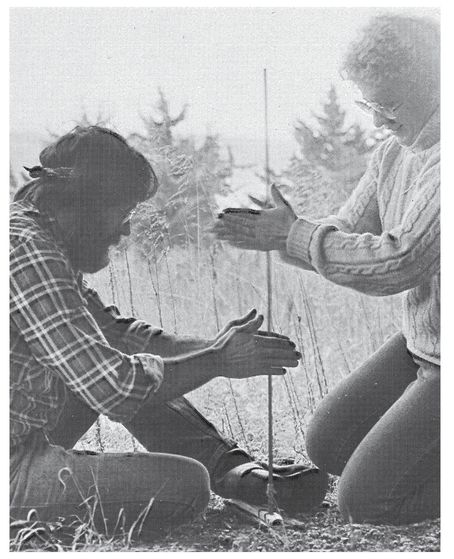

By using a longer drill and superb teamwork, two people can make this easier by keeping the drill spinning constantly. It takes two working in harmony—one set of hands picking up the drilling at the top precisely when the other set leaves off at the bottom.

Another two-person variation that I’ve come up with (I haven’t heard or seen this anywhere else), this is by far the easiest of the hand drill methods that I’ve worked. Use a bearing block and have one person apply the downward pressure. The other spins the drill vigorously, instructing the “bearer” how much pressure to apply. The spinner, not having to apply the downward pressure, isn’t exhausted so easily, enabling the spark to be quickly made.

Cordage

To me, any description of the use of the bow/drill that doesn’t include the making of cordage is incomplete. Such a common thing as a piece of string just isn’t always in your pockets when you may be in need of fire, especially in a survival situation. And when you most need this fire (in winter cold and damp), you don’t really want to tear your clothing up to make a string. Even if you did, you may not know enough about how to prepare it to keep it from breaking under the stress you’d place on it when using the bow and drill.

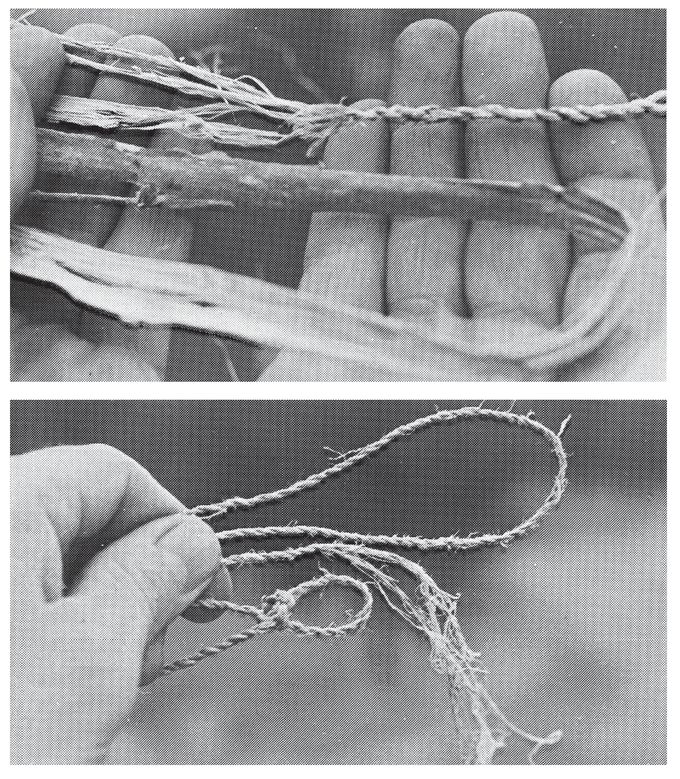

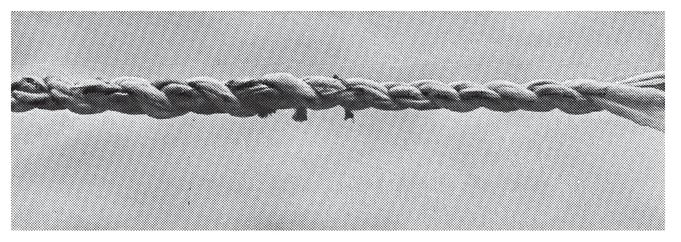

Hemp cordage still attached to the unprepared strip. Stinging nettle cordage. This piece “made fire” with the bow and drill.

This section will teach you how to make usable cordage of the kind that’s able to withstand the use of the bow and drill. I’ve personally used the cordage types that I state are suitable for this. I’ll also mention by name others that I’ve heard or read about but not tested myself. Some readers of this book are likely to have with them certain valuable items (handkerchief, dog fur, human hair) in the most primitive situation, and may find others commonly afield. For additional sources, once you’ve soaked up the information contained herein, you can experiment, letting your imagination be your limit.

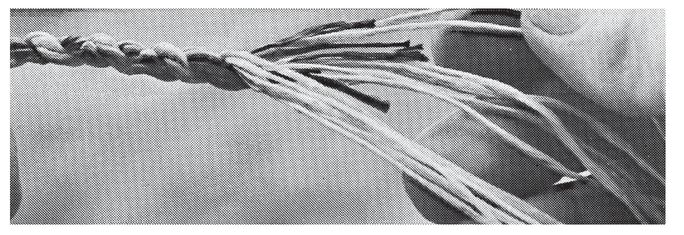

Black and white strands hanging from fingers. Twisting the blacks tight clockwise for about 1/2” and then twisting that counterclockwise over the whites and twisting the whites clockwise. By continuing this simple process you end up with cordage.

Making Cordage

I’ll attempt to describe this simple craft by words—something not so simply done. I’ll also use photos of my own, since I’m more adept at taking them than at arranging words.

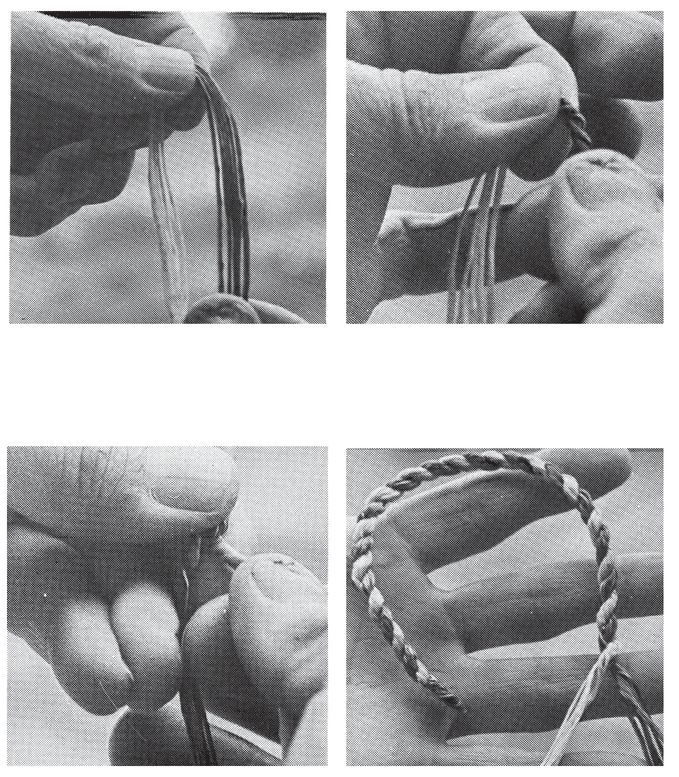

Let’s begin. Take several strands of thread; any kind or size will work. Let’s just make them 3’ long for this demonstration. Lay them out on a flat surface and use a magic marker (or anything similar) and dye the strands black or dark for one third of their length (that’s 1’, folks). You don’t have to dye them; the color is added simply to make the process more understandable on this trial run. Pick this bunch of strands up at the point where the dye begins. Now, you have hanging from your fingers two lengths of strands, one being 2’ long and white, the other 1’ long and black. Correct? You right-handers hold them between the thumb and forefinger of your left hand. Let’s say that the shorter black strands are now the ones uppermost in your grip. Begin with these (my reference to these individual strands will now be references to either the black or the white—still with me?). Now, take these black strands and twist them tightly clockwise (that’s to your right) for 1/2” or so. Twist the now-twisted black strands counterclockwise, over the yet-untwisted whites; hold them securely. Now, twist the whites clockwise and twist that over the blacks counterclockwise. You’ll find yourself always working the top bundle as they switch places.

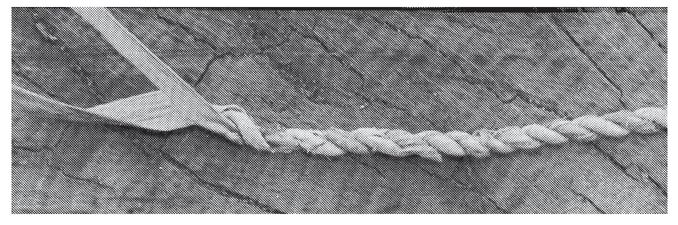

That’s it—the entire secret. Just keep doing this till you’re within a few inches of the end of a strand, and splice in more, to continue for as long as you like. (See photos on page 27.) Keep the splices at different intervals on the two sections, to keep the whole stronger. Constant splicing of few fibers makes for a stronger whole. The twisting clockwise of the individual strands and twisting them counterclockwise into one strand is the way to do it. The contrary twisting holds the whole damn thing together. It’s a very simple concept—till one tries to put it into words.

With this knowledge, your life in the wilds takes on a new dimension. You don’t have to think for very long before the possible applications start forming in your mind. From threads to ropes, the list of uses for cordage is endless.

Cordage materials need to be strong enough for the task at hand, but also must be pliable. Although dry grass would certainly be strong enough for the bow or drill (as well as numerous other uses), its brittleness makes it unusable. It would break immediately just tying a knot.

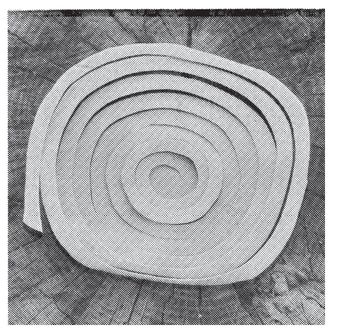

We’ll begin with what you’re likely to have with you when thrown into a survival situation: a neckerchief or scarf, or something similar. Tear this into strips approximately 1” wide (a normal neckerchief is about 18” square). Pick up the first strip as with the fibers (in thirds) and begin the twisting action as described above. When reaching the end of one strip, I tear the last 2” into thirds (also with the new spliced-in strand) to help interlock the splice, and on I go. When I reached 3 1/2’ with the kerchief I was working, I quit with 5 strips left over. (See bottom photo opposite.) The advantage to being able to use this technique is that in a survival situation you might have access to a T-shirt, or some bandages from a first aid kit. The list of possibilities goes on.

If you’re lucky enough to get lost with a furry critter, so much the better. I worked with the underfur of a dog and found that I had an unlimited supply on hand. It wasn’t all that difficult to get the hang of working with it, either, though different than the longer fibers I’m more accustomed to.

In a few hours, I ended up with a good solid rope about 3 1/2’ long. When making fire with the fur, though, I found that it stretched easily and slipped badly on the drill, till I wetted it—then it worked like a charm. You might also come across the carcass of a furbearer (coon, coyote, and the like) where enough leftover fur might be lying around. (See photos on page 28.)

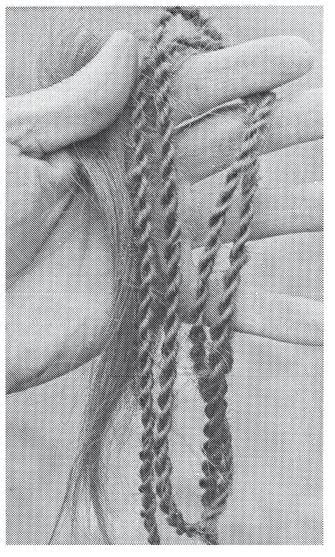

Something that most people will have with them is a supply of hair. If things got tight, you could cut your own. This works well. I ended up with a good strong rope in little time (not my own—donated by Margie’s Country Image). The hair that I worked with was about 6” to 8” long, though a bit shorter would also work. Again, it’s easier to work with if wetted first.

Plants for Cordage

The list of fibrous plants that can be used for cordage is long. I won’t cover them all, as I don’t know them all. I’ve never worked with dogbane (also called Indian hemp), which I’ve heard is about the best plant around.

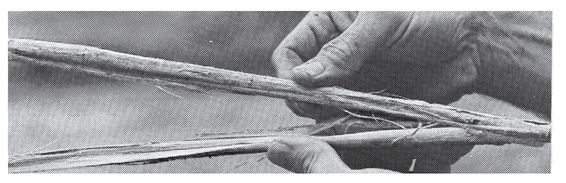

Stinging nettle, velvetleaf, and hemp (marijuana) are three similar, widely distributed, and common plants (weeds?). All make a good, strong cordage easily capable of withstanding the stress of the bow and drill. Using dried plants, I take a rounded rock and lightly pound them to break the stalk, and then tear this into strips (roughly thirds). I then begin at the top of the plant, “break” the inner material, and then “strip” the outer layer loose.

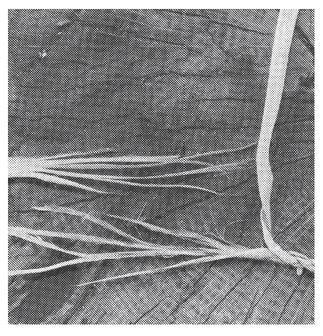

Additional fibers ready to splice in.

Halfway spliced.

The finished splice.

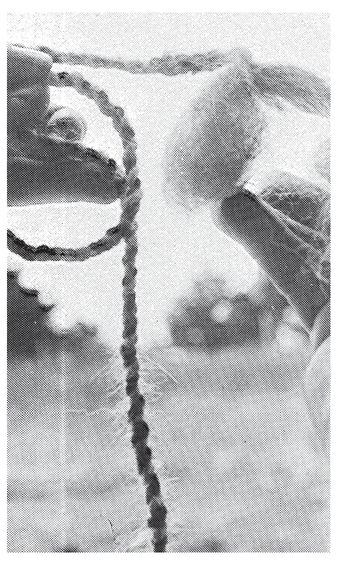

Cordage from neckerchief strips.

I follow down the plant, breaking and stripping about every inch (this works better than just stripping the outer fibers, which will tear easily). (See photos opposite.) I end with a rough strip, maybe 2 1/2’ to 3’ long. This I gently roll between my fingers or my palms to separate the fibers and to remove the chaff. What I end up with is suitable for cording.

Dog fur.

Human hair.

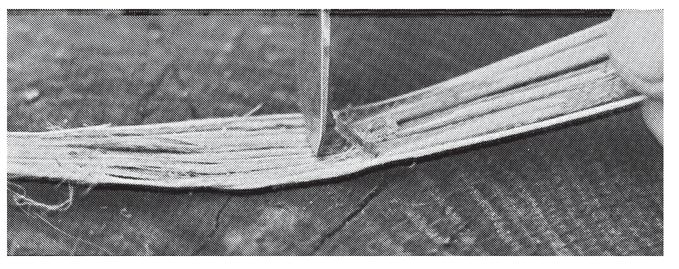

The leaf of the yucca gives a strong fiber that’s also easy to work. It can be used either green or dried. With the yucca leaf, the fibers are inside. Take the dried leaf and beat it gently to separate the fibers some. This helps it to soften faster while soaking. Then soak the pounded leaves till supple. When your yucca is partly or fully green, take a rounded knife blade (flint or otherwise) and scrape the outer covering from both sides (the soaking makes this easier with dried leaves). Then work the fibers loose by rubbing back and forth with your fingers. Superb cordage material.

Gently pounding the stalk.

Pulling the stalk of dogbane apart.

Breaking the inner stalk and stripping it from the fibers.

You can come up with additional usable fibers with only a little experimenting. When in the timber or fields, just grab different weeds and grasses as you go along, break them, and try to separate the fibers. If they hang together in strips, try using them. Grass will work and can be fashioned into a great rough cordage suitable for baskets, mats, or insulating liners to winter camps.

While on the subject of plants, let’s not forget tree barks. The inner barks of many are fibrous and work superbly, as with the fibrous plants. Cedar makes a fast though weak cord. Look around a bit in your area to find what’s available. Not often thought of, the inner or outer nonfibrous barks of most trees will work well also, especially for the emergency bow or drill. What I used in my test was the inner bark of the Osage orange (I was debarking bowstaves). First removing the rough outer bark, I then carefully withdrew thin strips of the next layer. The average length I ended up with was about 3’, a super-good length. I cut these down to about 1/4” widths and shaved them till about 1/16” thick. This individual strip I then used as I would a bunch of strands, twisting away. When I reached the end of a strip, I cut about 2 1/2” of the ends to splice into my many thin threads, and continued on. This made one of the best quickie bow or drill strings that I’ve worked with (besides maybe rawhide). Once dried, it wasn’t worth a damn—too stiff and brittle, plus you can’t cord it when dry. But when wet (green), superb! Caution: When using the bark from any live tree, though, do so only in an emergency, as it damages the tree (and could even kill it). If it’s necessary to use a live tree, take individual strips of bark from several. This helps to ensure the life of the tree. It also would be better for the tree if you stripped the bark from the branches.

Scraping off the outer covering of the yucca leaf.

The spiny-tipped wild yucca plant.

Solid piece of bark ready to splice.

Splice halfway worked.

Finished.

Animal Material for Cordage

Now, let’s discuss some animal material. Sinew (tendons) supply some of the strongest cordage available. An animal is loaded with sinew in various lengths. The longest and the easiest to work with are the long strips running down either side of the backbone (silver colored, lying on top of the meat, running from under the shoulder to the hip). Sinew is most easily removed with a dull knife, to prevent accidentally cutting it. Scrape it clean and then lay it out flat to dry. It works easiest if dried first, then broken and separated into threads of the appropriate size, and finally wetted again before cording. The resulting strong cordage was the most common of the Indian bowstrings. The shorter tendons of the legs are also usable, only not as easily since they’re shorter and thicker, which makes them harder to separate and work with.

Deer rawhide cut 1/4” wide.

After soaking, doubling, and twisting, then stretched to dry.

Rawhide for Cordage

Rawhide is another good cordage material. It’s best used after it’s dried, primarily because drying eliminates stretching (note that I’m still talking string for the bow or drill!). With rawhide, I don’t actually “cord” it. Instead, I double it and twist it up fairly tight, stretching it and tying it off at both ends to dry. I find that the doubling, twisting, and stretching eliminate the stretching while in use (I use this for bowstrings); add strength; and also help the rawhide to grip the drill better. I cut the deer rawhide 1/4” wide, a width that seems to be plenty strong enough. I’ve shot up to several dozen arrows through 55- to 60-pound bows that I’ve made, and have yet to have one rawhide string break.

Wild weeds: velvetleaf and hemp.

I once took a squirrel skin and cut it in a circular strip about 1/2” wide, leaving the hair on (as if under a primitive situation). Then I twisted it tight, but not doubling it, and made fire with it the very first time. (I had trouble keeping it tied to the bow, because with the hair on and the skin green, the knots didn’t want to work all that well.) The string, as would any green or wet rawhide, stretched badly and took much finger control to keep taking up the slack. Also, after the first fire, I was unable to use the same drill till after it had dried. The moisture from the skin got the drill so wet that it did nothing but slip. Once it was dried again, though, I had no trouble.

But enough about cordage. You’ve now got sufficient information to go out, identify certain usable plants and other materials, work with them, and put them to your use. You also have learned enough to be able to search out and experiment, to come up with many more. This is not an exact science. Just bear in mind the important rules of length and pliability of the material used.

A Coupla Fire-Making Tips

Kennie Sherron of Ponca City, Oklahoma, sent me the following two firemaking ideas. They will add greatly to the methods explained in this chapter.

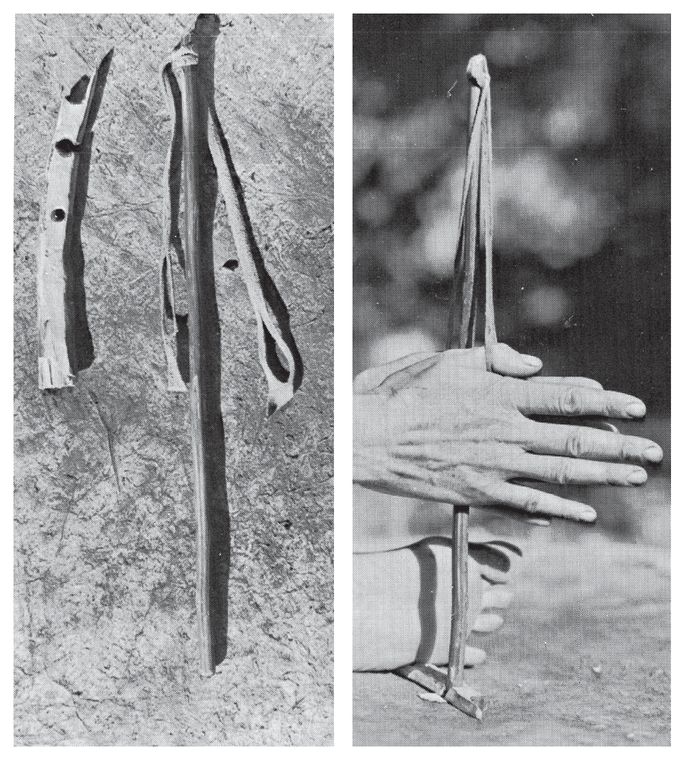

A fire drill, as Kennie describes it, for the Indian who has it all. Made from deer leg bone, it’s squarish and will never “round.” The bone being hollow, it’s reinforced at both ends to prevent splitting (here with rawhide). The piece shown is permanent, to fit into the bearing block. The lower piece, pulled out here, is a replaceable soft tip. When I first got this in the mail, I just kinda put it aside, but carried it along for show-and-tell. Well, at one set of demos we actually ran out of usable drills near the end of the second day, after more than a hundred-plus fires. But we did have some short pieces of yucca, and so gave this a try. I knew that it would work but was unprepared for how well it worked. The squarish bone spins like a champ in the bow, and the extra weight of the overall drill gave me much better control. And, most importantly, we now had enough fire drill tips for several hundred more fires. I like it!

Another, probably more important, tip for a fire-maker lacking a helper: this one for the hand drill, whose use, even under the best circumstances, is never easy. It’s a piece of cordage (or, as illustrated here, a strip of brain-tanned buckskin) with slits cut for the thumbs, tied to the upper end of the drill (and also tied over it, in most cases). The thumbs placed in the slits provide constant downward pressure, letting you constantly spin the drill. Makes starting a fire almost easy, and greatly increased my successes.