Working the Crowd:

Elgar, Class, and Reformulations of Popular Culture

at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

DEBORAH HECKERT

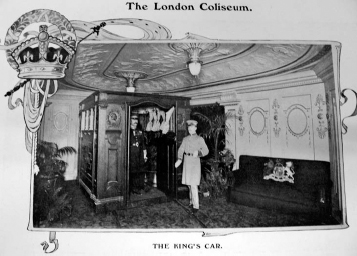

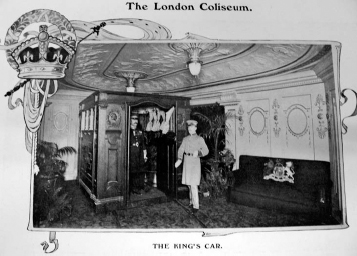

Opened in 1904 by the visionary impresario Oswald Stoll, the London Coliseum was arguably the most opulent of the Edwardian music halls. It had a particularly unusual feature: an enormously expensive conveyance christened the “King’s Car.” This clumsy, elephantine contraption was a lavishly decorated anteroom on wheels that ran for twenty-six yards on a series of tracks; it was designed to whisk the king and his guests from their carriages directly through a special Royal Entrance to the door of his box. Thus His Majesty would not have to mingle with—or indeed, so much as glance at—any of his subjects. Instead, unsullied by propinquity to the lower classes, the monarch could partake of an entertainment only recently beginning to distance itself from working-class associations. In his lively history of the London Coliseum, The House That Stoll Built, Felix Barker relates the tragicomic fate of the King’s Car:

The only recorded occasion on which this unique piece of transport had a chance to prove itself came on a visit by Edward VII. This was shortly after the opening of the theatre, and was the first visit ever paid by a member of the Royal Family to a variety theatre. The royal party climbed in, the manager gave the signal. But instead of moving softly along its tracks, the car stayed quite still. The King passed it off as a joke, but the car never recovered from the disgrace.

Covered in ignominy, the King’s Car was banished to the Stoll Theater where it gathered dust until it was eventually converted into a supplemental box office during the 1920s.1

Figure 1. An early photograph of the King’s Car at the London Coliseum.

Elgar, too, might have wished for a hermetically sealed (or hermeneutically sealed) “Composer’s Car” to whisk him through the portals of his fraught interactions with the popular culture of his day. For the composer’s engagements with mass culture—and the attendant accusations of “vulgarity” leveled at him by elitist critics—have raised some of the most problematic questions in the study of Elgar reception by both his contemporaries and later commentators.2 Since the topic of Elgar’s relationship to popular culture is extraordinarily complex, this essay seeks to explore ways in which envisioning Elgar crossing the Coliseum’s threshold might open the doors for an investigation of the popular, vulgar spaces available to artists during the fin de siècle. Barry J. Faulk and others have argued that new forms of entertainment arising in the late nineteenth century allowed for the transcending of class barriers. In marked contrast to the dubious working-class entertainments of the mid-Victorian period, widely considered by the authorities to be socially disruptive and unsuitable, a new version of popular culture developed as part of a bourgeois field of activity.3 By turning a critical eye on Elgar’s participation in the popular culture of his era, we may well arrive at a clearer understanding of his engagement with modernity.

For Elgar, who reached the height of his fame in the early years of the twentieth century, an aspect of being a “modern” composer was to step boldly into the arena of mass popular culture, especially as the “popular” had gained new respectability due to its associations with the genteel middle classes. Given Elgar’s family background, his alliance with the middle class was a comfortable and natural step up in social status. Elgar’s father was a provincial piano tuner and freelance musician who raised himself from working class to the lower-middle class by going into trade as part owner of a music shop in Worcester. Despite Elgar’s marriage to a woman who enjoyed a markedly higher social status and his subsequent conflicted attempts to play the county gentleman, the composer was forever branded by some denizens of upper-class society as a social climber from the lower-middle class.4 The extent to which Elgar’s biographers dwell on the class conflicts inherent in his career and character attests to the centrality of this issue. Positioning Elgar against the backdrop of a newly respectable and increasingly uniform middle-class version of mass culture now helps us gain insight into a whole range of Elgar’s compositions that were regarded, in his lifetime and after, as problematic because of their supposed vulgarity. A partial list of such “vulgar” scores might include the Pomp and Circumstance marches and the many works designed to celebrate coronations and other civic occasions; “salon” music, such as Salut d’amour; and much of the incidental music written for theatrical productions. All of this music may be viewed, as it is by Charles Edward McGuire, as “functional music.”5 By composing functional music that appealed to an expanding bourgeois audience, Elgar demonstrated that he was a savvy professional who accurately assessed the possibilities, fiscal and otherwise, that popular culture offered to a British composer during the first decade of the twentieth century.6

A prerequisite to gaining greater insight into this phenomenon is an exploration of the times and places in which Elgar purveyed music to the masses. Such an investigation must take place on multiple planes, encompassing both the metaphorical and the concrete. An apt place to begin is in the music halls (also known as “variety palaces” or “variety theaters”), which functioned, as noted above, as prominent loci of popular entertainment in the years preceding the First World War. The culture of the music halls has recently attracted a lively amount of attention from historians who study the rise of popular culture, but Elgar’s place in this milieu has rarely been examined in depth.7

In 1912, Elgar composed a spectacular masque, The Crown of India, op. 66. By creating this piece of functional music, the composer passed the threshold of more than the Coliseum, for he also entered into a metaphorical space understood at the time as “modern.” Furthermore, in that same step, he traversed a series of class boundaries: the slumming royals, the boisterous working classes, and the respectable bourgeoisie. Recent scholarly work on Crown of India rightly investigates its overt imperialistic and orientalist aspects: the score can be viewed as a nexus for issues of national identity and colonial “otherness” that permeated British cultural productions during the late-Victorian, Edwardian, and, indeed, Georgian, eras. Nalini Ghuman, for example, offers an insightful exploration of the imperialist underpinnings of Crown of India in her essay “Elgar and the British Raj: Can the Mughals March?” in this volume. These accounts present a fascinating picture of how the details of the music and production commingled to uphold a set of musical and dramatic conventions that served to encourage (and maintain) the then popular ideologies of empire. Instead of viewing the score through the lens of colonial studies, however, this essay concentrates on the particularly modern artistic and public stance that Elgar adopted in exploiting imperialist tropes within the larger contexts of audience and mass culture.

The Crown of India as Popular Entertainment

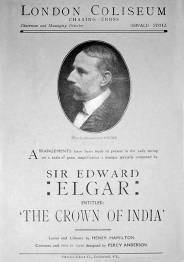

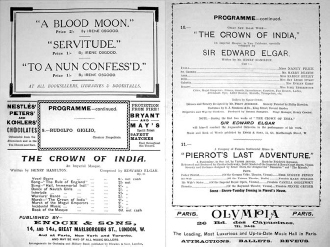

The commission for the Crown of India masque came from impresario Oswald Stoll, who sought Elgar’s prestige and popularity for the London Coliseum in order to celebrate the state visit of King George V to India in December 1911.8 Stoll planned a sumptuous production for the Coliseum, with a budget of over £3,000 for fabulous costumes and elaborate sets. He hired popular actors and actresses, including the celebrated Nancy Price in the role of “India” (figures 2a and 2b).

The elaborate libretto was concocted by the playwright and littérateur Henry Hamilton. His text for Crown of India exalted British colonial power as if it were still at its historical peak rather than already in the process of an inexorable decline. (Nalini Ghuman has provided a synopsis of Hamilton’s libretto in her discussion of Crown of India.) Not content to fill the stage with the several groups of dancers, personifications of cities, and the putative national characteristics of both Britain and India, Stoll crowded in courtiers, soldiers, attendants, pages, natives, and a multitude of “etceteras,” providing an opulent visual display that played directly to his public’s colonialist fantasies. In Stoll’s vision, India was characterized as an exotic dreamland firmly controlled by a benign British military, abetted by commercial interests. India was therefore controlled within the space of the theater by the modern gaze of an audience of British consumers.

Figures 2a and 2b. Publicity stills of Nancy Price as India from the Coliseum production of The Crown of India.

For this spectacle, designed to cater to the longings of the newly emerging lower-middle and middle classes, Elgar created a richly varied score: introductions, melodramas to support speeches, songs, interludes, and marches that reflect the stereotyped characteristics of an orientalist mode. These sections mined musical representations of non-Western locales that were used throughout the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth.9 Such characteristics—including discreet chromaticism, “exotic” percussion, and piquant harmonies—had long been exploited by British composers who specialized in short, light orchestral works often featured prominently in concert halls such as the Crystal Palace. Such exotic tropes are also found in music for the theater, both serious and comic, and above all in the extensive corpus of parlor songs with orientalist lyrics, such as Amy Woodforde-Finden’s famous “Kashmiri Song.”10 In Crown of India, these standard elements of exoticism emerge in music designed to characterize the “East,” whereas British characters are portrayed through hearty diatonic tunes.

Once the score was complete, Elgar threw himself enthusiastically into preparations for the premiere.11 He conducted cast rehearsals, both for the chorus and the soloists, often as accompanist at the piano. He rehearsed the pit orchestra as well. During the first two weeks of the run, Elgar conducted two performances of the masque daily, and often called additional rehearsals as needed. This tremendous effort exhausted the aging composer and, by its end, exacerbated an inner ear problem that ultimately required a stay in a nursing home.12

Crown of India was first performed on March 11, 1912; Elgar’s participation in its run ended on March 23 (figures 3a and 3b). The production was unquestionably a commercial success. Nevertheless, some critics at the time—and several commentators since—considered it beneath a composer of Elgar’s stature: the creation of such a frankly commercial score could not be received with universal approbation.13 Concerns about the composer’s involvement in a populist spectacle were voiced by a reporter who interviewed him for the Standard just before the premiere of The Crown of India. In response, Elgar mounted a public defense:

Sir Edward Elgar would commit himself to no special opinion regarding his first definite contribution to the programme of a big music-hall. “It is hard work, but it is absorbing, interesting,” he said, during pause in the proceedings. “The subject of the Masque is appropriate to this special period in English history, and I have endeavoured to make the music illustrate and illuminate the subject.”14

Elgar’s statement reads as a thinly veiled attempt to give the commission greater dignity through an appeal to patriotism. However, the composer’s motives for accepting such commercial projects were more personal in nature.

In his account of the period from 1910 to 1912 when the masque was composed, Jerrold Northrop Moore reveals Elgar’s anxiety over his persistent financial difficulties, especially the debts accrued through the composer’s ill-considered move into Severn House, a large and expensive edifice in Hampstead. Stoll’s lavish budget for the masque included a sizable fee for the composer, with additional funds for Elgar if he agreed to conduct it during the first two weeks.15 Elgar wrote a somewhat defensive letter to Frances Colvin outlining the fiscal benefits of the masque:

Figure 3a. A playbill publicity insert for the Coliseum production of The Crown of India.

Figure 3b. A program for an evening at the Coliseum in March 1913, including The Crown of India

When I write a big serious work e.g. Gerontius we have had to starve & go without fires for twelve months as a reward: this small effort allows me to buy scientific works I have yearned for & I spend my time between the Coliseum & the old bookshops … Also I can more easily help my poor people [his brother and sisters’ families]—so I don’t care what people say about me—the real man is only a very shy student & now I can buy books… . I go to the N. Portrait Gallery & can afford lunch—now I cannot eat it… .

My labour will soon be over & then for the country lanes & the wind sighing in the reeds by Severn side again & God bless the Music Halls!16

Whether the money was spent on such purchases, or whether Lady Elgar used it to pay the servants’ salaries at Severn House, is unknown.

Although the pecuniary rewards of such popular commissions obviously held their appeal for Elgar, he also respected his colleagues at the Coliseum. The timing of the Crown of India commission was suspiciously apposite, as Stoll’s extensive connections in society may have let him hear rumors of the composer’s unstable finances. Stoll was well-known for his successful approaches to “serious” music and theatrical personalities, overtures that were timed to coincide with periods when these artists were short of ready money.17 Stoll’s shrewd premise was that once the great and good, baited by cash, encountered the Coliseum’s high artistic standards and respectability, they would become advocates.18 Clearly, Stoll’s strategy worked with Elgar: in the letter to Colvin quoted above, Elgar also wrote, “It’s all very curious & interesting & the people behind the scenes so good & so desperately respectable & so honest & straight-forward—quite a refreshing world after Society—only don’t say I said so.”

The obvious financial rewards of this commission were clearly not the only inducement for Elgar. As Corissa Gould has observed, he had no qualms about turning down commissions he did not feel suited his temperament, either musical or ideological.19 Rather, Elgar and his wife enjoyed the Coliseum. During the production’s run, Alice Elgar, whose standards of propriety were high indeed, repeatedly took friends and family to the Coliseum to view the entertainment.20 She wrote proudly in letters and diaries of the glories of the production and her husband’s music in a way that strongly conflicts with the notion that either Edward or Alice was embarrassed by the composer’s involvement with the Coliseum.21 Indeed, Elgar relished attending the Coliseum over the years: seeing a performance there of the ballet Little Boy Blue danced by Anton Dolin and Ninette de Valois inspired the composer to send Dolin his Nursery Suite to choreograph as a ballet.22 In 1918 Elgar wrote another work for Stoll and the Coliseum, Fringes of the Fleet, a setting of verse by Rudyard Kipling. In producing works for the Coliseum and its mass audiences, then, Elgar sought to fulfill at least part of what he conceived to be his responsibility as a modern British composer.

The Nineteenth-Century Music Hall

If neither Elgar nor his wife were embarrassed by the composer’s sally into Stoll’s Coliseum, then we should not be surprised at the imperialist ideology embedded in his music hall pieces. Recent investigations by Dave Russell, Penny Summerfield, and Peter Bailey have shown that jingoistic sentiment—a chauvinistic celebration of the British Empire—was an essential feature of a successful music hall revue.23 New data on the content of music hall acts reveal that the sorts of imperialist ideologies represented by Crown of India were present even in the performances by comic singers in workingclass variety palaces. Imperialism was therefore joined inextricably with popular culture in late-Victorian, Edwardian, and Georgian music halls. The songs of the music hall stars were at times ambivalent about particular aspects of Britain’s imperialist ambition and the impact of empire building on the lives of workingmen and women, especially during the Second Boer War. Overall, however, support for Britain and its empire, found in overt displays of patriotic sentiment, was a signal way in which the music halls managed to create a unified audience from a disparate group of spectators across a spectrum of class backgrounds.

But even as positive sentiments toward imperialism seemed to transgress the class boundaries of fin-de-siècle Britain and imply some sort of unity between these classes, the reality was that class distinctions were sharply drawn even within the walls of the music halls—as the very existence of the King’s Car suggests. Any reading of the popular culture found in the middle-class Edwardian and Georgian music halls must take into account the populist (and at times rowdy) characteristics of the earlier incarnations: the variety palaces that flourished during the second half of the nineteenth century that were also known as the “late-Victorian” or “working-class” music halls.

During the transition between the Victorian and Edwardian eras, the “new” and “modern” music halls (as well as other emerging forms of mass entertainment) provoked both fascination and anxiety on the part of contemporary commentators. Such commentators lacked an adequate frame in which to position inherited attitudes against the onrush of modern influences. Since the general populace enjoyed a previously unknown amount of leisure time, access to early twentieth-Century sites promoting popular entertainments increased. These venues were surrounded by anxieties emanating from late-Victorian attitudes toward social control. Music and music making were particularly implicated in Victorian strategies for controlling the actions and attitudes of society, especially those of the working class.

Music was securely bound to the Victorian ideal of “moral uplift.” Victorians of the ruling class sought to use didactic imperatives to support the continuance of a class-based system; in this context they tried to control the putatively undisciplined and volatile working classes through the medium of an artistic culture imposed from above. The result was an attempt to denigrate—or at times erase—popular music making that originated from within the working classes themselves. But for all the Victorian rhetoric of disapproval, which was often a nostalgic attempt to deny contemporary reality, popular music that arose from the working classes forced its way into visibility within institutions that were valued as modern. To the Victorians, the music halls represented a dangerous but enticing brand of modernity.24

One British artist who celebrated the music halls was the painter Walter Sickert (1860–1942), who created several canvases dating from the 1890s that portray the variety palaces in ways that suggest their modernity.25 Sickert’s writings frequently valorized the music hall as an appropriate topic for the modern artist, and he practiced what he preached.26 Sickert was particularly drawn to the lively music halls in Islington and Camden; his nocturnal jaunts were habitual and became legendary, since he walked miles to attend these variety palaces, returning late at night on foot to his residence in the much more exclusive suburb of Hampstead.

Sickert’s keen, unsentimental eye is evident in such paintings as The P.S. Wings in the O.P. Mirror. (Sickert’s title alludes to the “prompt side” and “off prompt” side of the stage.) In this canvas, a reflecting mirror separates the space of the painting into two contrasting perspective planes, heightened by differences in scale (figure 4). Sickert’s other music hall paintings present even more of a visual puzzle evoking his multivalent and essentially modern attitude to his subject. Indeed, Sickert’s paintings can be viewed as a mirror that reflected, through the use of new techniques such as skewed perspective, the tensions—class, gender, and aesthetic—that arose as the new lower-middle and middle classes began to define themselves within the 1890s variety palaces. An example of Sickert’s ingenuity in this regard is his canvas of a lone audience member propped up against a mirror, which creates a vertiginous array of backdrops, wings, mirrors, and raking perspectives (figure 5). The intricacies of Sickert’s paintings constitute an eloquent portrayal of the music hall during the 1890s, as well as how perspectives, both literal and figurative, were changing during this period of transition.

Figure 4. Walter Sickert, The P.S. Wings in the O.P. Mirror. Rouen, Musee des Beaux-Arts.

The predecessors to the music halls that Sickert painted in the 1890s were various kinds of public meeting places that combined drinking and music, such as the supper club and music-licensed taverns. Music halls as such did not appear until the 1850s.27 During the 1860s, they multiplied until there were over three hundred such establishments in greater London alone. By the early 1870s, music halls had assumed a regular design: a proscenium arch marking a definitive stage area, bars serving alcohol at the back of the hall, and frequently a promenade area where men and prostitutes might open negotiations.

The Oxford Music Hall was the most notorious of these establishments. When it came time to renew its license, this particular hall served as a target for attacks by several organizations dedicated to the preservation of public morality; these attacks represented just a few of the many overt attempts to close or constrain these variety theaters.28 Perceived as contested sites of modernity as well as immorality, the music halls and the debates that swirled around them reflected larger ideological concerns that flared up during the 1880s and ’90s. These centered on the dangers of popular culture and the frightening instability of the urban working classes.

By the 1890s, music halls had sprung up in London’s suburbs such as Camden Town and Islington—the halls frequented by Sickert—as well as in the new theater and entertainment district around Leicester Square in London’s West End.29 Neighborhoods determined the style of hall; suburban halls catered to the new “clerk” class of the petit bourgeois, a direct result of a dramatic increase in white-collar workers on the lower end of the pay scale. The older, poorer neighborhoods of the East End were home to halls frequented by members of the working class. Larger, more opulent establishments were clustered around Leicester Square and Charing Cross, where proximity to rail stations allowed travelers of all sorts to stop in at the Oxford, the Empire, and the Alhambra—which meant that these halls had to maintain at least a veneer of respectability.

In the early 1890s, these larger venues began to diversify their programs in order to appeal to new middle-class audiences by including variety acts; the Alhambra even made ballets a particular feature of their nightly offerings. However, this high-toned fare was more the exception than the rule; most music halls still appealed predominantly to working-class and lower-middle-class audiences. The success of the halls relied heavily on stars, especially comic singers such as Albert Chevalier, Harry Lauder, Marie Lloyd, and Katie Lawrence. Their songs were popularized not only by performances in the halls, but through sheet music which sold widely across Britain. A song’s success was based solely on the reputation of the star with which it was associated rather than the composer or lyricist. The songs dealt mostly with quotidian topics, some sentimental, most comical, and many pervaded by sly sexual innuendo. These popular songs were designed to mirror the audiences they targeted, treating with humor the trials and tribulations of love, courting, marriage, work, and other subjects. Recent discussions of music hall songs stress their conservative nature: these songs were hardly a call to revolution. Despite this conservatism, the songs nevertheless expressed a particularly working-class perspective that would have been considered modern at the time.

Figure 5. Walter Sickert, Vesta Victoria at the Bedford. Private collection of Richard Burrows

Although it would be a mistake to downplay the wide variety of social, political, and ethnic backgrounds represented by the individuals who made up the music hall audiences—London audiences in particular were notable for their diversity—music hall songs articulated a shared experience, creating both solidarity and camaraderie. The sense of solidarity is attested to by the audience’s participation in refrains of their favorite songs, and the give-and-take between audience members and the “Chairman” who acted as a master of ceremonies, as well as with the stars themselves.30 There were a number of opportunities for an audience to interact with the stars, as these privileged performers appeared more than once during the course of an evening. Acts were paid by the “turn,” or appearance onstage, and only established stars would perform more than one turn a night. The second turn, usually scheduled for around 10 P.M., was always the most desirable, since it was then that the hall had the largest audience, as opposed to the first turn at 8 P.M. and the third at midnight.

Another reason for the music hall’s popularity among working-class clientele was the relatively cheap admission prices: a seat in the stalls by the Chairman’s table cost two shillings, a seat in the gallery a mere sixpence. Furthermore, an audience member could get back in drink half the cost of admission. With prices like these, affordable even to a member of the urban working class, it is unsurprising that the music halls were hugely popular, sometimes with nearly a thousand people crowding into the theater.

But as the popularity of the music halls rose in the 1880s, so did governmental fears about the putatively deleterious effects of such raucous and risqué entertainments on public morals, and the variety palaces came under a closer scrutiny. Increased governmental intervention resulted in the growth of licensing laws and regulations controlling safety in the halls and the content of variety acts. The mid-to-late 1890s was a transitional period as these new regulations began to take effect. Music hall proprietors, fully cognizant of social pressures—and aware of the profitable potential of more genteel audiences—sought to gentrify their establishments.

Edwardian Reconfigurations

Hastening the changes that occurred during the second half of the nineteenth century, initiatives were made in the early twentieth by newly formed music hall amalgamates to avoid confrontations between theater owners and local governments over the issues of working-class rowdiness, temperance, and prostitution. The key to the success of these initiatives was modification of outdated formulas in order to appeal to a new middleclass clientele. Music hall proprietors shrewdly realized that the most important change needed to cultivate this particular audience was to attract middle-class women. If they could entice middle-class feminine spectators into their establishments, the families of these women would quickly follow. By this time, Stoll’s Coliseum, like halls in London’s West End, with its “round-the-clock variety” that ran from noon to midnight, was designed specifically to appeal to an audience that included large numbers of women with their families in tow. These respectable audience members were often suburban visitors to London who sought harmless but diverting entertainment on their excursions. Catering to this new kind of audience obviously had an enormous impact on the kinds of acts presented in Edwardian music halls: the Victorian working-class halls’ emphasis on the comic solo was sharply reduced, if not eliminated totally, and replaced instead by an array of acrobats, dancers, animal acts, and extended spectacular features that appealed to patriotic sentiment—as in The Crown of India.

Given the highly varied composition of the audience on any given night, a convenient fiction was thus perpetrated by the impresarios and amalgamates who had a financial stake in the success of the variety palaces: an imaginary audience consisting entirely of middle-class families. This construct, at odds with reality, proved powerful and successful. It was attractive to consumers of all classes who were invested in maintaining a facade of social respectability—especially the lower-middle class aspiring upward. The fiction flattered both the bourgeoisie and those who aspired to be so, and was invoked to determine the acts’ content and, by extension, generate ideologies of representation and consumerism.

The result of these reforms was that widely mixed audiences from all strata of the urban and suburban population flocked to the music halls. This diversity was reflected by the wide range of entrance prices, which theoretically made seats available for every income bracket. Along with aristocrats and the bourgeoisie, working-class spectators of both sexes still attended the variety palaces, of course, as well as the grandees who had patronized the louche late-Victorian halls.

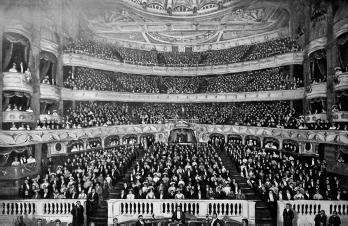

The theater’s cleverly calculated appeal to a decorous, feminized middle class is evident in a brochure published and distributed by Stoll in 1906.31 Lavishly illustrated, on heavy paper and embellished with gold, the publication concretized in its materials the goals of the management; it was cannily designed to convince a wide audience of the opulence, distinction, “culture,” and above all, propriety of the Coliseum (figure 6). But Stoll’s genius in promoting this perception of respectability served a related function that further legitimized his claims. Stoll used his advertisements, along with promises of lavish remuneration, in order to woo performers, composers, and artists who normally inhabited the world of high culture, such as Elgar. Like a set of facing mirrors reflecting off each other, the prestigious cultural products of such creators further confirmed the essential respectability and high tone of the Coliseum.

The pamphlet stated that the Coliseum was built “to attract that huge class which believed the variety theatre to be in bad odour and would not in consequence visit it.”32 Much of the brochure is devoted to vivid descriptions of the beauty and tastefulness of the decorations, up-to-date stage machinery, and the Coliseum’s restaurants and cafés. The pamphlet forcibly outlined the dramatic changes to the music halls, stating, “It would be very little if the atmosphere and environment had not undergone a similar process of purification. It was desired to make attendance at this playhouse as respectable as going to church.”33 The brochure further claimed that “the Coliseum is like going to a friend’s house—everything is so homely and domestic and in good taste” (figure 7).34 Statements expressing Edwardian and Georgian ideologies of class and gender run through the brochure’s text. Moreover, sharp distinctions along class lines between the old music hall—which was “only the resort of a class”—and the modern Coliseum, a “space sufficient for each of the little worlds that go to make up society, each to enjoy equal facilities and, in a way, equal accommodation”35 (figure 8). Finally, the feminization of this space was linked to the broadening of the audience’s class base:

It must be noticed by all visitors to the Coliseum that its audience is largely made up of women and children, conspicuously in all parts of the house. Society ladies, sitting in the boxes and stalls with their children, have not been quicker to seize the opportunity which are offered for bright, wholesome entertainment than the wives of the artisan, who, with their numerous progeny, crowd the balconies, proving in the most conclusive manner that the pit is quite as eager and capable as the stalls of responding to a genuinely artistic appeal.”36

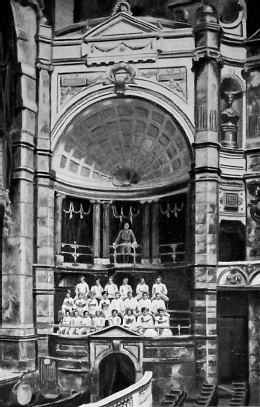

Figure 6. Opening illustration in the publicity publication To the Coliseum.

Music was a serious and carefully considered part of the ideological program advanced by Stoll and the management of the Coliseum: “It will surprise the uninitiated to know what infinite pains are taken to promote in the public a love for good music.” A considerable amount of space in the promotional brochure was expended on describing the classically trained vocalists in the house choir, the organ and organist, and the quality of the music (figure 9): “It is not a music hall in any acceptance of the term; but a ‘music-theatre,’ where high-class renderings of the greatest scores may be heard which, aided by the cultured interpretation given them, can be thoroughly enjoyed.”37 The pamphlet specifically mentioned opera scenes presented by the noted diva Alice Estey and a staged excerpt from Gounod’s popular Faust that had recently been featured at the Coliseum.

Despite such claims, the frequency with which “serious” art music was programmed at the Coliseum was erratic. Stoll’s commission of Crown of India represented an exception rather than the rule, and Elgar’s music was, after all, commissioned to adorn the elaborate libretto rather than as a serious extended piece of music in its own right. At the Coliseum, like most variety palaces, art music was considered just one of the many building blocks used to construct the elaborate edifice of an evening’s entertainment. Sometimes these classical selections were unexpected, as when Stoll staged scenes from Parsifal during the 1913 season, the first time extended excerpts from Wagner’s music drama had been heard in London.38 In 1912, the year before this excursion into Wagnerian territory, the “Milan Opera” performed Leoncavallo’s I Pagliacci at the Coliseum. More often, however, scenes and selections from longer works were scheduled as part of the rotation of turns within the three-hour shows, and light orchestral pieces were used as filler. Elgar’s Salut d’amour, for instance, turns up occasionally on the list of an evening’s offerings.39 It was mainly through the popular ballets that audiences heard music by serious composers, since spectacular ballets and pantomimes—of which Crown of India was just one example—were hallmarks of the Coliseum, the Alhambra, and the Empire. For instance, the new revue of January 1913, titled Keep Smiling, included an “Assyrian” ballet featuring music by Glazunov, Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin, Goldmark, Ravel, Arends, and Montague Ring.40

The quantity of art music played in the various Edwardian and Georgian music halls is less important than the belief, shared by management and audiences alike, that such high-class works belonged there. At the same time, audience and management seemed to agree that just a smattering of highbrow music was enough, and such pieces were squeezed in between the acrobats, shadowgraphists, sharpshooters, and comic singers. This unspoken agreement, too, helped to constitute the modern identities of the new music hall audiences.

Figure 7. “Domesticity” at the Coliseum one of the several tearooms.

Figure 8. A view of the Coliseum’s auditorium

Figure 9. The “cultured interpreters” of the Coliseum as “music theater”—the Coliseum choir.

The presentation of scenes from Parsifal is a case in point. This production attracted great attention at the time: the distinguished conductor Henry Wood directed an augmented orchestra; the noted designer Byam Shaw created the sets and costumes; and an elaborate program was printed to provide spectators with the story, background materials, and brief discussion of the selections, all designed to whet their appetite and enhance their enjoyment.41 But the Parsifal excerpts occurred within the context of a normal night out at the Coliseum. The bill began with an overture, followed by Australian dancers, a comic duo, ragtimers, and a female comic singer. The big novelty of the season, the Parsifal tableaux, appeared in the spot immediately after intermission. It was followed by a short play with music, Max Pemberton’s David Garrick. The evening ended with Austrian woodcutters and a “Kinemacolour” presentation. The sequence of turns preceding and succeeding Crown of India was similar.42

Significantly, a new version of popular culture emerged from these evolving forms of mass entertainment for middle-class audiences. John MacKenzie has asserted that during the Edwardian period intellectual and popular tastes converged to an extent encountered at perhaps no other time.43 Elgar certainly hoped to appeal to the broadest possible Edwardian audience. By crossing the threshold of the Coliseum, however, Elgar became a pawn in the Edwardian game played by Stoll and other impresarios that sought to efface class distinctions, especially with respect to artistic taste, for commercial gain.

Elgar as “Public Poet”

How might Elgar be positioned as a voice for (or against) this newly emerging popular culture linked to the middle class? J. H. Grainger has identified and characterized the role of the “public poet” during the first decade of the twentieth century, and it may well be useful to imagine Grainger’s description as a metaphorical space into which a composer of functional music, such as Elgar, might enter profitably. The role of “public poet” is especially relevant if this composer chose to address the issue of imperialism within the context of mass culture, as Elgar did so conspicuously in Crown of India. Grainger has defined the “public poet” as one who

reminded, reassured, mobilized, sang praises and identified enemies within an objective, easily recognized world. Far from illumining their own subjective wholenesses, they were content to tell men what they already knew… . The poet repeatedly affirmed sentiments and told the tale again and again. As the public poet of a wide successful imperium he was not bardic. Bards are for lost or submerged patriae. Yet like the bard he looked for the heroic, the singular in the familiar story, emphasizing not freedom broadening down from precedent to precedent, not the long slow march of everyman, but deeds that made the realm and Empire… . The public poet invoked, exhorted, clearing not muddying the springs of action.44

Grainger’s description of the poet who rehearsed over and over what the people already implicitly felt about England aptly fits much of Elgar’s functional music. A persistent demotic attitude characterizes scores, such as Pomp and Circumstance March no. 1, as the veritable embodiment of English national identity. It is therefore illuminating to think of Elgar reflexively assuming the voice of a “public poet” in music, one who sings on behalf of his entire nation.45 With Crown of India, Elgar’s assumption of a public voice is augmented by the nationalist implications of its genre, that of the “masque.”

To have written a masque during the Edwardian period meant that the composer firmly positioned such a work within a venerable and uniquely British tradition stretching back hundreds of years, through Purcell to the Elizabethans. The Edwardian and Georgian masque composers sought to signify “Englishness” musically in ways that gestured toward popular culture, especially in the mediation of traditional components like spectacle and allegory.46 Many of these elements of the masque are clearly present in Crown of India; thus Elgar’s entrance into the Coliseum was made through an aesthetic portal provided by a genre that has traditionally linked celebrations of “Englishness” with popular spectacle.

Younger contemporaries of Elgar who also participated in the revival of the masque, such as Ralph Vaughan Williams, were enticed in part by the genre’s historical resonances, combining the musical and the literary with the artistic. Vaughan Williams pointedly used the designation “masque” to imply connections between his own music and that of the glorious Tudor past.47 While this is far from the only reason that he was interested in the genre, part of Vaughan Williams’s ambition was to validate certain constructs of British history, such as the glorification of the Elizabethan age. In this way, composers like Vaughan Williams were inoculated to a degree from the contagion of vulgar, popular modernity—the contemporary life that Elgar seemed to promote in accepting the commission for Crown of India. But unlike the putatively “historical” masques of his younger colleagues, Elgar’s work confronts instead the hunger of the middle class for a reflection of their own concerns. By writing for the Coliseum, Elgar avoided historical nostalgia and instead cultivated the role of the “public poet.”

Elgar was usually unwilling to claim explicitly the status of “public poet.” He displayed the same ambivalence in this regard as he did for most of the personae that he adopted, preferring—especially as he grew older—to let others, such as George Bernard Shaw and Ernest Newman, make such claims on his behalf. Elgar, however, permitted occasional glimpses of his outlook on the relationship he had with the British public. The most famous (or notorious) of these instances occurred during lectures he delivered in 1905 as part of the Peyton Professorship at the University of Birmingham.48 Among several controversial assertions found in these lectures, Elgar repeatedly criticized those British composers (clearly referring to his archenemy Stanford) who eschewed the challenge of the contemporary through recourse to historical materials. When alluding to the musical glories of the past, he stated unequivocally, “I think it unnecessary to go back farther than 1880.” In Elgar’s opinion, the trend in English music toward a dry academic historicism—“to sing ‘Ca ira, ca ira’ chanted to the metrical tune of the ‘Old Hundredth’”—would cause irrevocable damage to the development of native art, since from the “big music” of the last twenty-five years “we had inherited an art which has no hold on the affections of our own people.” His severest criticism of such music is that it is “commonplace”:

Critics frequently say of a man that it is to his credit that he is never vulgar. Good. But it is possible for him—in an artistic sense only, be it understood, to be much worse; he can be commonplace. Vulgarity in the course of time may be refined. Vulgarity often goes with inventiveness, and it can take the initiative—in a rude and misguided way no doubt—but after all it does something and can be and has been refined.”49

Obviously, Elgar evinced no distaste of vulgarity per se—by which he meant strong emotion, not the bawdiness of the late Victorian comic song. Instead, he distrusted any music, high or low, that does not engage with its audience, no matter how that audience was constituted. Accusing his more academic colleagues of composing music for one another’s delectation, Elgar states forthrightly, “Is it possible to conceive that Bach or Beethoven or Brahms so wrote for a narrow circle? No, they addressed a larger party, a responsive, human and artistic mass, and amongst these we find our greatest supporters.” He warned the “youthful English composer” not to “misjudg[e] his own strength—the public his works are to meet: I mean, of course, not that he should compose with a view to please a certain audience, but he should, on the rare occasions of a performance, choose a work suited to the occasion.”50

In 1905, there were cogent distinctions to be made about audiences, the absence of which reveals a certain lack of clarity in Elgar’s bold assertions, as well as his ambivalence about what sort of listeners constituted an audience for meaningful English music. On the one hand, he repeatedly warned young composers not to pander to the “popular public,” but in his lectures he seemed to be concerned with the cynical exploitation of the wider public just for fame and easy profit.51 As an alternative to easy fame, Elgar urged young British composers to imagine an audience consisting of thoughtful people drawn from all walks of intellectual and artistic life. Yet as some of the assertions quoted above demonstrate, Elgar demanded that composers take a wider public into consideration as well, even going so far as to recommend that, in giving “people’s” or “cheap concerts,” organizers should eschew condescension in the selection of repertory:

When good music is offered to the people, there is too much of an attitude of Sterne about the givers. When Sterne saw the hungry ass—he, after much thought, gave him a macaroon. His heart, he says, smites him that there presided in the act more pleasantry in the conceit of seeing how an ass would eat a macaroon than of benevolence in giving him one. Now—the English working-men are intelligent: they do not want treating sentimentally, we must give them the real thing, we must give them of the best because we want them to have it, not from mere curiosity to see HOW they will accept it.52

In this quotation, Elgar’s remarks demonstrated an implicit tension, if not contradiction, between Victorian assumptions about what sort of music was appropriate to each social class and an instinctual realization by the composer of “Land of Hope and Glory” that the new century had ushered in a decided shift in cultural power. Elgar’s assertions also shed light on his relationship with the Coliseum, as the music halls of the early twentieth century helped to amalgamate the previous disjunctions between lowbrow and highbrow into a somewhat disjointed but powerful middleclass cultural aesthetic, that of the “middlebrow.” Just like the music halls that he so enthusiastically blessed in his letter to Colvin quoted earlier, Elgar self-consciously desired to create a relationship with wider modern audiences that provided new compositional stances but still maintained an overarching musical aesthetic aimed squarely at the educated bourgeoisie.

The unresolved tensions and inconsistencies found in Elgar’s opinions have given rise ever since to problematic views concerning the relationship between Elgar’s music and popular culture. For Elgar to have written music for Stoll’s Coliseum was not, as some have suggested since the premiere of Crown of India, merely egregious opportunism by a great composer in need of ready cash. He did need the money at that point, surely, but as we have seen, remuneration was not the whole story. Elgar took this compositional opportunity as a means of reaching eclectic new audiences, and he achieved this goal by assuming the role of a “public poet.”

When Elgar strode into the Coliseum, he entered a space peopled in large part by an exuberant audience who demanded contemporary music that reflected its concerns. The later reputation of Elgar’s popular commercial works, considered in many twentieth-Century histories of British music as subsidiary to his art music, should not blind us to the composer’s personal interest and enthusiasm when he composed Crown of India in 1912. Elgar’s willingness to adopt a compositional attitude calculated to appeal to a diverse public—to adopt the emerging popular culture of that public—was a daring gesture for a serious composer of his time. Taking their cue from this model, musicologists might profitably explore the different environments, both physical and metaphorical, that Elgar inhabited and explored throughout his career, positioning them against the rapidly changing ways by which these spaces were being defined (and redefined) during the socially transitional years of the Victorian, Edwardian, and Georgian periods. Such efforts will surely result in a more nuanced view of the composer and his music, for, beyond the Coliseum, where else can we find Elgar?

NOTES

I wish to thank Jenny Doctor and Byron Adams for their help and advice in the course of completing this essay, as well as express gratitude for the pioneering work of Robert Anderson, Nalini Ghuman, and Corissa Gould on The Crown of India. Also, thanks to the Victoria and Albert Museum for all the images related to the London Coliseum.

1. Felix Barker, The House That Stoll Built (London: F. Muller, 1957), 18. The Coliseum is now the home of the English National Opera.

2. One notorious example of a musicologist characterizing Elgar’s music as “vulgar” was E. J. Dent’s tart opinion of the composer written in 1924 for Adler’s Handbuch der Musikgeschichte. Dent’s assertions were only seriously challenged when the second edition of the Handbuch appeared in 1930. An anguished cry of indignation was then sounded by Elgar’s defenders. Somewhat unexpectedly, it was the sardonic modernist composer Peter Warlock who gathered signatures from leading musicians of the day, as well as eminent supporters such as George Bernard Shaw and Augustus John, for an “open letter” of protest praising Elgar. See Robert Anderson, Elgar (New York: Schirmer Books, 1993), 167. Dent’s opinions are frequently cited in discussions of Elgar’s character, popular appeal, and literary pretensions. Brian Trowell neatly summarizes the reception of Dent’s comments over the years in his “Elgar’s Use of Literature,” in Edward Elgar: Music and Literature, ed. Raymond Monk (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1993), 182–287.

3. Barry J. Faulk, Music Hall and Modernity: The Late-Victorian Discovery of Popular Culture (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2004).The classic discussion of emerging forms of Victorian leisure activity and the attendant class ideologies remains Peter Bailey, Leisure and Class in Victorian England: Rational Recreation and the Contest for Control, 1830–1995 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978).

4. Most of the current biographies of Elgar discuss this aspect to a greater or lesser extent. An essay by Meirion Hughes offers perhaps the most focused discussion of Elgar’s problematic relationship to his family background and subsequent efforts to project a more genteel identity. Meirion Hughes, “The Duc d’Elgar: Making a Composer Gentleman,” in Music and the Politics of Culture, ed. Christopher Norris (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989), 41–68.

5. Pertinent chapters on Elgar’s functional music found in The Cambridge Companion to Elgar, ed. Daniel M. Grimley and Julian Rushton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004) include J. P. E. Harper-Scott, “Elgar’s Unwumbling: The Theatre Music,” 171–84; Charles Edward McGuire, “Functional Music: Imperialism, the Great War, and Elgar as Popular Composer,” 214–24; and Diana McVeagh, “Elgar’s Musical Language: The Shorter Instrumental Works,” 50–62. See also Daniel M. Grimley’s essay in this volume.

6. Not that Elgar was alone in this ambition by any means; for instance, his archrival Charles Villiers Stanford also sought to compose popular, lucrative works and succeeded with oft-performed (and patriotic) choral works such as The Revenge. See Jeremy Dibble, Charles Villiers Stanford: Man and Musician (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 178–79. Stanford never ventured into the music halls, however.

7. There is a large, fascinating bibliography on the music hall, truly interdisciplinary in the range of fields from which it has emerged. Besides Barry J. Faulk’s magisterial book, a list might include the collection of essays Music Hall: The Business of Pleasure, ed. Peter Bailey (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1986); Dagmar Kift, The Victorian Music Hall: Culture, Class, and Conflict, trans. Roy Kift (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996); and the wonderful section on the music hall in Dave Russell’s Popular Music in England, 1840–1914, 2nd ed. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997).

8. King George V’s Delhi Durbar was a huge event, exciting intense interest in the British media. Part of the royal tour of India, the Durbar was a modern court occasion, when Indian princes assembled to pay homage to the ruler. As an “invented tradition,” in Eric Hobsbawm’s terms, this sort of ceremony was perfectly geared for the imposition of a new British ruler on Indian soil. For more on the fascinating impact of the event on the imaginations of the British people, and how this was fueled by emerging media technologies, see Corissa Gould, “Edward Elgar, The Crown of India, and the Image of Empire,” Elgar Society Journal 13, no. 1 (March 2003): 25–35.

9. Robert Anderson has recently prepared an edition of the score for the masque for the Elgar Complete Edition, vol. 18, (London: Elgar Society with Novello, 2004). Despite the pervasiveness of the exotic idiom in music during the nineteenth century, particularly in Britain, musicological investigations of the ways in which the orientalist impulse mapped onto British musical composition and its reception are relatively limited. Recently there has been a rise of interest. See especially Nalini Ghuman Gwynne, “India in the English Musical Imagination, 1890–1940,” Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2003. Jeffrey Richards offers an overview of the subject in Imperialism and Music: Britain 1876–1953 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001). Finally, for a pan-European look at critical approaches to the subject of orientalism, see the collection of essays edited by Jonathan Bellman, The Exotic in Western Music (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1998).

10. For a discussion of such songs, see Derek B. Scott, The Singing Bourgeois: Songs of the Victorian Drawing Room and Parlour, 2nd ed. (Aldershot: Ashgate Press, 2001), 177.

11. Barker, House That Stoll Built, 179.

12. Jerrold Northrop Moore, Edward Elgar: A Creative Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), 629–30.

13. Diana McVeagh, for example, has characterized the music of Crown of India as “trumpery in a colourful and dashing manner.” See Diana McVeagh, “Elgar” in The New Grove Twentieth-Century English Masters, ed. Stanley Sadie (New York and London: W. W. Norton, 1986), 44.

14. 1 March 1912, as quoted in Moore, Elgar: A Creative Life, 629.

15. Gould, “Edward Elgar, The Crown of India and the Image of Empire,” 25.

16. Letter to Frances Colvin, 14 March 1912, as quoted in Moore, Elgar: A Creative Life, 630.

17. Barker, House That Stoll Built, 179. In the first three chapters, Barker paints a vivid picture of Stoll’s peculiar but successful style of management.

18. Stoll was right: Elgar convinced the actress Mary Anderson to appear at the Coliseum in 1917, citing his own happy experience there; see Barker, House That Stoll Built, 135.

19. Gould, “Edward Elgar, The Crown of India and the Image of Empire,” 29.

20. Both Edward and Alice Elgar may have been further reassured by Stoll’s own high standards of respectability, for he neither drank nor smoked and swore only on the rarest of occasions; see Barker, House That Stoll Built, 53.

21. Ibid., 27.

22. Anton Dolin, a major star, had been premier danseur with the Ballets Russes; see Richard Buckle, Diaghilev (New York: Atheneum, 1984), 413ff. For Elgar’s interest in having Dolin choreograph his Nursery Suite, see Barker, House That Stoll Built, 158–59.

23. See Russell, Popular Music in England, 1840–1914; and Bailey, Leisure and Class in Victorian England; as well as an essay by Penny Summerfield, “Patriotism and Empire: Music Hall Entertainment, 1879–1914,” in Imperialism and Popular Culture, ed. John M. MacKenzie (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1986), 17–48.

24. For more on the anxiety over musical halls and their role in working-class life, see Kift, The Victorian Music Hall: Culture, Class and Confict, in particular chaps. 5 (“1860–1877: The Demon Drink”) and 6 (“1875–1889: Programs and Purifiers”).

25. Walter Sickert was one of the most important British artists in the decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century. A student of the self-consciously modern Whistler, he came under the influence of Degas and thus was firmly rooted in French Impressionism and committed to the “painting of modern life.” Sickert remained a successful artist throughout his life, his style changing with the times, and also was extremely important as a teacher and mentor to younger British artists. For more information about Sickert and his music hall paintings in particular, see David Peters Corbett, “Seeing into Modernity: Walter Sickert’s Music-Hall Scenes, c. 1887–1907,” in English Art 1860–1914: Modern Artists and Identity, ed. David Peters Corbett and Lara Perry (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), 150–67, and Walter Sickert (London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 2000). Anne Greutzer-Robins discusses Sickert’s knowledge of the music hall scene in “Sickert ‘Painter in Ordinary’ to the Music Hall,” in Sickert Paintings, ed. Wendy Baron and Richard Stone (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

26. Walter Sickert, Writings on Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933), 14.

27. Barker, House That Stoll Built, 29–30.

28. For the politics and social conditions involved in this contest over relicensing, see Tracy C. Davis, “The Moral Sense of the Majorities: Indecency and Vigilance in Late-Victorian Music Halls,” Popular Music 10, no. 1 (1991): 39–52. For the Oxford Music Hall controversy, see Faulk, Music Hall and Modernity, 75–110. Oswald Stoll’s own churchgoing in-laws considered such theaters as “sinful homes of the devil”; see Barker, House That Stoll Built, 50.

29. Such “variety palaces” were found in most of the larger towns and cities across England as well as in London.

30. The Chairman played an important role in the music halls until the 1890s, introducing the turns and keeping order; see Barker, House That Stoll Built, 30.

31. Anon., To the Coliseum (London: Raphael Tuck and Son, 1906).

32. Ibid., 8.

33. Ibid., 6.

34. Ibid., 6

35. Ibid., 3, 7.

36. Ibid., 6

37. Ibid., 18.

38. The timing of these excerpts from Parsifal was largely the result of a copyright issue. See Barker, House That Stoll Built, 177.

39. For instance, the program on February 9, 1913, was sponsored by the National Sunday League. “A Grand Orchestral Concert with the Meistersingers Orchestra, conducted by Mr. Norfolk Megone. Mix of songs, orchestral favorites, Viennese waltzes, the William Tell overture, Elgar’s ‘Salut d’Amour’ and Three Dances from German’s Henry VIII.” The Coliseum program is in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum Theatre Archives.

40. I have not been able to trace the identity of the composer “Arends” mentioned in this program. But given the frequent misspellings of the foreign composers’ names in ephemeral documents of the time such as this one, it is entirely possible that this composer was actually Anton Arensky, a Russian who had written ballet works in an orientalist vein.

41. The program even included musical examples explicating Wagner’s musical dramas. The scenes from Parsifal presented:

1. Killing of the Swan

1b. Towards the Castle of the Grail

2. Amfortas Administering the Grail

3. Ejection of Parsifal from the Castle of the Grail 4a. The Magic Garden

4b. The Temptation of Parsifal by Kundry 4c. Kundry Repulsed by Parsifal 4d. Parsifal and the Spear

5. The Overthrow of Klingsor’s Splendour

6. The Flowery Mead

7. The Healing of Amfortas

8. Redeeming Love

Coliseum program, March 1913, Victoria & Albert Museum Theatre Archives.

42. On the program: A family of gymnastic equilibrists / Tom Stuart in dramatic and burlesque impressions / Thora, a ventriloquial novelty / Billy Merson, the new London eccentric comedian / Dmitri Andreef, the famous Russian solo harpist / Miss Irene Vanbrugh in J. M. Barrie’s “The Twelve-Pound Lock” / Rudolfo Giglio, chanteur napolitain / Crown of India / A company of famous Continental mimes in “Pierrot’s Last Adventure,” with music by Fridrich Bermann and produced by the Viennese ballet master Charles Godlewsky. Coliseum program, March 1913, Victoria & Albert Museum Theatre Archives.

43. John M. MacKenzie, “Introduction,” Imperialism and Popular Culture, 1–16.

44. J. H. Grainger, Patriotisms: Britain 1900–1939 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986).

45. It is important to emphasize that the voice of the “public poet” was only one of many personae adopted by Elgar, both in his life and works. It is enough to say here that the negation of personal subjectivity, which is in some way demanded by the utterances of the “public poet,” was a source of personal conflict for a composer whose work seems in many ways replete with autobiography and self-representation. Few Elgar scholars today, influenced by the seminal work of Jerrold Northrop Moore and Byron Adams, would argue that Elgar could ever project a unitary identity.

46. See Deborah Heckert, “Composing History: National Identity and the Uses of the Past in the English Masque, 1860–1918,” Ph.D. diss., Stony Brook University, 2003.

47. Ibid., passim.

48. In 1905, Elgar was offered the new Peyton Chair in Music at the University of Birmingham. Richard Peyton had endowed this position with the stipulation that it would be offered to Elgar. Elgar was not enthusiastic about the offer, worried that his lack of academic credentials made him unqualified for the job, and justly fretted that his busy schedule would be further complicated by the addition of new responsibilities. However, with the creation of the professorship at stake, and with persuasive arguments from friends and colleagues in Birmingham, Elgar accepted the post. Part of his responsibilities included delivering a set of public lectures. Elgar gave seven lectures between 1905 and 1906, many of which proved quite controversial, before his resignation in 1907. See Percy Young’s introduction and commentary to Edward Elgar, A Future for English Music and Other Lectures, ed. Percy M. Young (London: Dennis Dobson, 1968). See also Moore, Elgar: A Creative Life, 446–48, 456.

49. Elgar, A Future for English Music, 33, 41, 47–49.

50. Ibid., 37, 89.

51. Ibid., 41–43.

52. Ibid., 213.