Elgar’s War Requiem

RACHEL COWGILL

This is already the vastest war in history. It is war not of nations, but of mankind. It is a war to exorcise a world madness and end an age.

—H. G. Wells, The War That Will End War

While Elgar’s patriotism and sense of Empire have been treated with considerable insight in recent years, Elgar scholarship seems to have found it relatively difficult to explore objectively the religious and denominational contexts in which he lived, and their significance or otherwise for his music.1 Indeed, in some cases emphasis on the former has obscured the latter, as with Jeffrey Richards’s suggestion that The Dream of Gerontius can be considered an imperialist work on the grounds of Elgar’s identification with “the idea of Christian heroism,” exemplified by General Gordon of Khartoum.2 Where Elgar’s Catholicism has been broached in the literature, as Charles Edward McGuire discusses elsewhere in this volume, there has been a tendency to accept without much question two tropes that emerged shortly after Elgar’s death, which can be seen at least in part to have originated from remarks made by Elgar himself: the first of these, that a crisis of faith had rendered religion no longer of significance in his life (an identity McGuire refers to as the “Weak Faith” avatar); and the second, that as an English Catholic he had learned to appreciate and operate within the codes of Protestantism (the “Pan-Christian” avatar). Just as these avatars arguably offered Elgar himself a means of appeasing his Protestant countrymen and for dulling his often sharply felt sense of otherness within British society, they have also offered convenient strategies for his past biographers who perhaps either did not recognize the centrality of religious identity as a social dynamic in British society of the Victorian and Edwardian eras, reflecting the increasing secularization of subsequent generations, or whose view of their subject was filtered by a particular denominational position or personal belief.3

Scholars who have tackled the topic of Elgar’s Roman Catholicism directly have done so, understandably, in relation to his sacred and organ music.4 But Elgar’s Catholic identity can be seen to have a broader significance both for his art and for its place within English culture, as will be explored here in relation to one of his ostensibly secular vocal works, The Spirit of England, op. 80 (1915–17). This is a setting for tenor or soprano soloist, orchestra, and chorus of three poems from The Winnowing-Fan, a collection of verse published in the early months of the Great War by the poet, dramatist, and art scholar Laurence Binyon (1869–1943).

In his 1984 study of Elgar’s life and works, Jerrold Northrop Moore points to an interrelationship between the themes the composer worked with in his music and his religious beliefs:

The fortunes of Elgar’s faith can be traced in the subjects he chose for his major religious choral works, his treatment of those subjects, and how they intertwined with the more purely literary heroes for compositions, also of his own choosing.5

Yet Moore places The Spirit of England among Elgar’s imperialist works, reserving discussion of it for the chapter titled “Land of Hope and Glory” and denoting it “the other face of the Coronation Ode of 1902.”6 In this regard he echoes Donald Mitchell, who had remarked earlier on “Elgar’s convinced committal to what we may generally term ‘imperial’ topics (the Coronation Ode, Crown of India, Spirit of England and the rest).”7 Both writers are surely correct to highlight the overt nationalism of this score, which Moore emphasizes further by adopting its title for his book (Spirit of England: Edward Elgar in His World). At first glance Binyon’s poetry does not seem far removed from A. C. Benson and indeed many British poets writing in the autumn and winter of 1914. The opening stanzas revel in a version of Kipling’s “White Man’s Burden”—England’s mission to free those enslaved by ignorance and tyranny, to vanquish the forces of evil, and to spread the beacons of civilization—all couched in heady imperial imagery designed to stiffen the backbone in the face of mounting death tolls on the western front. Musically Elgar seems to respond in a like manner, with expansive, aspirational melodies built around upward leaps and rising sequences in full choir and orchestra, marked grandioso, nobilmente, and sonoramente.8 However, to accept unquestioningly this bracketing of The Spirit of England with Elgar’s imperialist works without further investigation would be to perpetuate the whiff of jingoism and propaganda that has lingered around the work, and which probably accounts for its neglect both in the concert hall and in the literature, despite the quality of the music and its significance within Elgar’s creative output.9 As will be seen, The Spirit of England can be interpreted as a specifically Catholic response to the outbreak of war in Europe, and understanding it as such can yield insights into Elgar’s changing attitudes to his faith—the faith in which he was immersed as a young child—and its relationship to his sense of heroic nationalism in the turbulent second decade of the new century.10 When taken out of context, Elgar’s words to Frank Schuster on hearing of the commencement of hostilities against Germany on August 4, 1914, can seem startlingly inhumane:

Concerning the war I say nothing—the only thing that wrings my heart & soul is the thought of the horses—oh! my beloved animals—the men—and women can go to hell—but my horses;—I walk round & round this room cursing God for allowing dumb brutes to be tortured—let Him kill his human beings but—how CAN HE? Oh, my horses.11

Volunteers were flooding to join the British Expeditionary Force across the Channel, but the British army was still perceived as a body of professionals; conscription would not be instituted for two years and the full horrors of trench warfare had yet to become a reality. Like many of the aristocracy with whom he aligned himself, especially as an enthusiastic racegoer, Elgar’s concerns were thus for the noble beasts that as cavalry mounts and draught animals had been crucial to Britain’s pursuit of the Boer War, and which epitomized the ideal of unwavering service and loyalty until death, most poignantly when slaughtered in their hundreds to sustain the besieged citizens of Mafeking (1899–1900).12 Frustrated that he was “too old to be a soldier,” Elgar signed up as a Special Constable within two weeks of the outbreak of war, and a few months later switched to the Hampstead Volunteer Reserve, involving himself in regular drills and rifle practice.13 He mobilized A. C. Benson into revising the words for “Land of Hope and Glory” and was soon devoting his creative energies to a range of small-scale compositions, including recitations with orchestral accompaniment of poetry by the Belgian patriot Émile Cammaerts (1878–1953): Carillon (op. 75, 1914), Une voix dans le désert (op. 77, 1915), and Le drapeau belge (op. 79, 1916).14

British poetic responses to the conflict began to flood the pages of newspapers and periodicals, and among the first were those published in the London Times by Elgar’s friend Laurence Binyon. By Christmas Binyon had gathered twelve of his poems into a single volume, The Winnowing-Fan: Poems on the Great War; from this collection, probably working from a copy given to him by the poet himself, Elgar took the following as the basis for a new cantata: I. “The Fourth of August” (referring to the day war was declared); X. “To Women”; and XI. “For the Fallen”; all of which are presented below.15 The elegy “For the Fallen” would become the most famous and lasting of Binyon’s poems, containing the prescient fourth stanza:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

Over the decades to come this quatrain would be recited during countless Armistice and Remembrance Day services and carved on many of the cenotaphs and war memorials erected across the British Empire. After the war, at the behest of the League of Arts, Elgar would rearrange his setting of “For the Fallen” for “Military or Brass Band, or Organ or Pianoforte” (later replaced by full orchestra), omitting the solo part, cutting three stanzas, more than halving the movement in length, and reworking his treatment of the central quatrain into a more consoling, luminous, and sparsely accompanied passage in E major. Renamed With Proud Thanksgiving, this version was intended for performance at the dedication of Edwin Lutyens’s Whitehall Cenotaph and the entombment of the unknown warrior in Westminster Abbey in 1920, though in the end hymn singing would be preferred by the organizers.16 As the third movement of Elgar’s The Spirit of England, “For the Fallen” would become a stock item in the BBC’s Armistice Day broadcasts, sometimes conducted by the composer himself.17 Elgar considered it equal in merit to The Dream of Gerontius and The Kingdom, and by 1933, Basil Maine could confirm that “for many [The Spirit of England] has become a national memorial to which they instinctively turn each year on Remembrance Day.”18

The idea of setting poems from Binyon’s The Winnowing-Fan appears to have been triggered by Elgar’s friend Sir Sidney Colvin (1845–1927), who, until his retirement as Keeper of the Department of Prints and Drawings, had been a colleague of Binyon’s at the British Museum. It was widely believed by the Allies that the war would be over by Christmas, and so by the first weeks of New Year 1915 the need was keenly felt for something that could help to make sense of the escalating carnage and offer consolation to the growing mass of the bereaved.19 Colvin probably discussed this with Elgar, for after spending the day with him he jotted the following postscript to a letter dated 10 January 1915:

Why don’t you do a wonderful Requiem for the slain—something in the spirit of Binyon’s “For the Fallen,” or of that splendid homage of Ruskin’s which I quoted in the Times Supplement of Decr 31—or of both together? —SC.20

That Elgar found Colvin’s citation of “For the Fallen” sufficiently appealing to set the text itself, along with others from the same collection, is perhaps not surprising. The verses are replete with musical references, which Binyon enhanced in an extra stanza he wrote for Elgar’s “Marziale” section (quoted below). As the son of an Anglican clergyman, Binyon also drew on a long familiarity with the language and imagery of the Bible in his poetry: for the famous quatrain in “For the Fallen” he later described how he had “wanted to get a rhythm something like ‘By the Waters of Babylon we sat down and wept’ or ‘Daughters of Jerusalem, weep not for me’ … and having found the kind of rhythm I wanted, varied it in other stanzas according to the mood required.”21 His disillusionment with institutionalized religion, however, and fascination with Eastern art and cultures (the main focus of his scholarship in adult life) brought to his poetry both an emphasis on humanism and a broad frame of reference, giving it an appeal that crossed denominational boundaries. His studies of William Blake’s apocalyptic visions might also have helped him to find a voice with which he could speak of the harrowing events of the war; and in “Louvain,” the sixth poem from The Winnowing-Fan, he expressed both a deep love for Flanders and his personal pain at the sacking of this ancient university town. (He did not at this stage know of the murder of his close friend Olivier Georges Destree, who had entered a Benedictine monastery there.)22 The extent to which in early 1915 “For the Fallen” seemed to capture the mood particularly of the nation’s noncombatants, and would do so increasingly over the course of the war, is underlined by Binyon’s biographer, John Hatcher:

“For the Fallen” is one of the few great war poems to include in its tragedy those “that are left.” It takes Henry’s St. Crispin’s Day speech from [Shakespeare’s] Henry V IV. iii, the key text of English chivalric patriotism, and turns it inside out, seeing the war and its aftermath from the point of view of those at home, the older generation too old to fight, including those who found their jingoistic platitudes stilled in their throat by the surreal nightmare the war had become.23

Colvin, Binyon, and Elgar all belonged to this “older generation”—“Do you realize that nearly half my life belongs to Victoria’s days?” Binyon quizzed T. S. Eliot in 1940—and of the three, only Binyon had direct experience of the fighting.24

The second text to which Colvin referred Elgar came from the final chapter in volume 3 of John Ruskin’s Modern Painters—this was an important, indeed crucial, book for Colvin, who had idolized Ruskin all his life.25 Writing during the Crimean War (1853–56), Ruskin takes as his theme “righteous” warfare, which he argues is essentially a better, more ennobling state for England than peace, referencing ancient codes of Christian chivalry:

I ask their witness, to whom the war has changed the aspect of earth, and imagery of heaven, whose hopes it has cut off like a spider’s web, whose treasure it has placed, in a moment, under the seals of clay. Those who can never more see sunrise, nor watch the climbing light gild the Eastern clouds without thinking what graves it has gilded, first, far down beneath the dark earth-line—who never more shall see the crocus bloom in spring without thinking what dust it is that feeds the wild flowers of Balaclava. Ask their witness, and see if they will not reply that it is well with them and with theirs; that they would have it no otherwise; would not, if they might, receive back their gifts of love and life, nor take again the purple of their blood out of the cross on the breastplate of England… . They know now the strength of sacrifice, and that its flames can illumine as well as consume; they are bound by new fidelities to all that they have saved—by new love to all for whom they have suffered; every affection which seemed to sink with those dim life-storms into the dust, has been delegated, by those who need it no more, to the cause for which they expired; and every mouldering arm, which will never more embrace the beloved ones, has bequeathed to them its strength and its faithfulness.26

Elgar’s own affection for Ruskin is apparent in his quotation of a passage from Sesame and Lilies on the last page of his score of The Dream of Gerontius. That he considered working directly with the text Colvin highlighted for him seems unlikely—it is, after all, prose rather than poetry—but in its message and atmosphere of heroic idealism it comes close to the poem he would choose for the opening movement of The Spirit of England, Binyon’s “The Fourth of August” (text quoted below). By 1915 most Englishmen believed their country was engaged in a just war, necessary to honor treaties and avenge the “rape of Belgium” by going to the aid of the smaller, weaker country overwhelmed by a foreign aggressor. In this manner, the war engaged highly developed notions of chivalric honor, manliness, patriotic duty, and, as David Cannadine has observed, an increased confidence that death, when it came, would come naturally and in old age, encouraged by the lengthening of life expectancy and decline in infant mortality in Britain since the 1880s. Combined with growing international tensions (including a concern that colonial youths were outstripping their home-grown counterparts in prowess and vigor) and the increasing appeal of social Darwinism in the 1900s, these factors had created the “strident athletic ethos of the late-Victorian and Edwardian public school … in which soldiering and games were equated, in which death was seen as unlikely, but where, if it happened, it could not fail to be glorious.”27 Such conditioning determined the conduct not only of the officers drawn from the public-school elite, but also those from the lower social ranks who emulated them, and can be seen to have been effected through music as much as through the literature and imagery of the 1900s (see, for example, figure 1).

Figure 1. Ezra Read, The Victoria Cross: A Descriptive Fantasia for the Pianoforte (London: London Music Publishing Stores, c. 1899). Note the detailed program.

The most striking aspect of Colvin’s proposal is that he should have prompted his Catholic friend Elgar to compose a “requiem for the slain,” a phrase that may owe something to Binyon’s habit of referring in private to “For the Fallen” as his “requiem-verses.”28 To someone with a Protestant background, like Colvin, the word requiem could be bandied quite lightly. Over the 1890s and 1900s English audiences had shown a greater willingness to accept choral works based on Roman Catholic liturgy; and in his discussion of Stanford’s decision to compose a requiem for the 1897 Birmingham Festival, Paul Rodmell cites freedom from librettists and potential copyright entanglements among the attractions of setting such a text.29 Yet to Elgar, raised as a Roman Catholic, requiem was inseparable from a particular view of the afterlife, especially the doctrine of purgatory—a process that allowed for the purification of the souls of repentant sinners in a slow agony and which could be hastened and even curtailed by the prayers of the living. By contrast, Protestant theology on the afterlife during the Victorian era was far more rigid: God’s judgment determined whether a soul ascended to heaven or was cast into the fires of hell for eternity, and the doctrine of purgatory was excoriated in the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Anglican Church.30

Byron Adams has described Elgar’s faith as never more than “a flickering light” and in a compelling narrative tracks the faltering of that faith through a downward spiral of physical and psychological corrosion as the composer struggled to complete his massive trilogy of oratorios, especially the final work The Last Judgement.31 Such was the extent of this apparent spiritual decline that the doctor who diagnosed Elgar’s terminal cancer remembered the composer telling him that “he had no faith whatever in an afterlife: ‘I believe there is nothing but complete oblivion.’”32 This must have seemed an astonishing remark to hear from the man who had composed The Dream of Gerontius over thirty years earlier. Similarly, in his last weeks Elgar’s friends and daughter were unsettled by his request to have his body cremated and his ashes scattered at the confluence of the rivers Severn and Teme; and although he reportedly received the “last rites,” it was only after he had slipped into morphine-induced unconsciousness. Elgar’s daughter Carice finally persuaded him to be buried alongside his wife, Alice, at St. Wulstan’s Roman Catholic Church, Little Malvern, and though a requiem mass was celebrated in his memory, it was a low mass without music.33

Whether one can fully accept Adams’s narrative of a crushing loss of faith, or set Elgar’s apparent ambivalence toward his Catholicism down to the obfuscation necessary for acceptance in Protestant British society, two considerations are fundamental to any discussion of Elgar’s spirituality. First, whatever his experience in late adulthood, and whatever the strength or otherwise of his faith, Elgar’s outlook and personal history were steeped in Catholicism: culturally, he always remained a Catholic. Until his departure from Worcester to London in his early thirties, he lived life in a Catholic context dominated by his mother, a fervent convert to the faith; he had attended Catholic schools and a Catholic church, had socialized with Catholics, and was organist at St. George’s Catholic Church in Worcester, which provided him with many of his earliest musical experiences including exposure to repertoire from the continental Catholic traditions. Catholicism would remain a strong influence on the women in his life—his wife would convert to Catholicism, and his sister became a senior nun at a Dominican convent near Stroud. Memories of boyhood would forever be inseparable from this “Catholic ethos,” to borrow John Butt’s phrase, as when Elgar reminisced about priests he had known as a child, for example, in conversation with the Leicester family on June 2, 1914.34

Second, in the sphere of religious music Elgar had to become adept at negotiating Protestant sensibilities. In his early career, before 1898, he composed a great deal of Latin sacred music, including a short hymn tune for the Marian devotion “Stabat Mater Dolorosa” and a number of individual mass movements, though he never attempted a complete setting of the Ordinary.35 In the years before the Great War, Elgar turned his attention to the composition of Anglican liturgical music, to the extent that John Butt describes him as “an Anglican manqué,” but his interest in Catholic music continued unabated.36 While on a trip to Italy in 1907–8, Elgar planned to obtain a copy of Giovanni Sgambati’s Messa di Requiem, which had been sung at Italian royal funerals and had been heard twice to great acclaim in Germany; perhaps he hoped this might reignite his inspiration as he struggled to complete his oratorio The Last Judgement.37 He suggested to Ivor Atkins, organist of Worcester Cathedral, that Sgambati’s Requiem might be suitable for a Worcester Festival Choral Society concert, or even the Worcester Festival of 1908, and laid plans to meet the composer personally while in Rome to discuss the loan of orchestral parts. In the end, however, the festival committee chose Stanford’s Stabat Mater (1906), a setting of a Catholic text by a safely Anglican composer.38

The most eloquent evidence of Elgar’s willingness to appease his Protestant countrymen remains his approach to the setting of Cardinal Newman’s “The Dream of Gerontius.” Newman’s poem required considerable truncation and simplification in order to render it suitable as a libretto. Elgar also seems to have wanted to shift the focus of attention away from Newman’s conception of the afterlife, toward Gerontius as a universalized suffering human figure, which, as McGuire observes, was characteristic of his approach in his later oratorios.39 Among the cuts Elgar was prepared to make were several passages of Catholic doctrine. The Guardian Angel’s words on leaving Gerontius in the care of the Angels of Purgatory were left out, for example, although the remaining text still clearly described a purging of the soul hastened by masses said by the living.40 Passages from Newman such as these caused Dean Spence-Jones of Gloucester to ban the work from performance in the cathedral there in 1901 and the Anglican authorities to stipulate textual alterations before Gerontius could be heard in Worcester Cathedral the following year.41 As Elgar outlined in a letter to Jaeger, on May 9, 1902, the problematic sections were the Litany of Saints recited at the dying man’s bedside, Gerontius’s beseeching of the Virgin Mary to intercede for him, and the references to the doctrine of purgatory in the final scene:

What is proposed is to omit the litany of the saints—to substitute other words for Mary & Joseph—& to put “Souls” only over the chorus at the end instead of “Souls in Purgatory” & to put “prayers” instead of Masses in the Angel’s Farewell… . So far I have only said I have no objection to the alterations or that I concur—permission I cannot give.42

For that permission the approval of Newman’s executor, Father Neville, had to be sought. In the end Neville concurred with Elgar on a bowdlerized version of the work designed for performance in an Anglican church; Elgar was sufficiently content to conduct this version himself at Worcester in 1902 and finally at Gloucester in 1910.43 Clearly, Elgar learned from these experiences: he took the precaution of having the text of The Apostles vetted by two Anglican clergymen before committing himself to the final version.44

In view of Elgar’s cultural roots in Catholicism, the faltering of his inspiration for The Last Judgement, his preparedness to make compromises for his Protestant audiences and patrons, and the fervency of his nationalism, we can speculate that Colvin’s invitation to write a requiem for the slain in the early months of the Great War would have been a powerful stimulus to the composer’s creative imagination. Having suffered Anglican censure of The Dream of Gerontius, however, Elgar would surely have been reluctant to court controversy again by composing a setting of the Latin Mass for the Dead. A requiem from his pen, as opposed to those of his Protestant countrymen, would need to take a less overtly Roman Catholic (and therefore less provocative) form; Binyon’s poetry would prove ideal for the composer’s purpose.

The verses Elgar selected from Binyon’s The Winnowing-Fan had been published in the Times at the outset of the conflict on August 11, August 20, and September 21, 1914. Elgar emphasized their local significance in an inscription on the completed score: “My portion of the work I humbly dedicate to the memory of our glorious men, with a special thought for the Worcesters,” and at the end, “For the Fallen & especially my own Worcestershires.” The text is as follows:

Movement I (Moderato e maestoso)

I. The Fourth of August45

Now in thy splendour go before us,

Spirit of England, ardent-eyed,

Enkindle this dear earth that bore us,

In the hour of peril purified.46

The cares we hugged drop out of vision.

Our hearts with deeper thoughts dilate.

We step from days of sour division

Into the grandeur of our fate.

For us the glorious dead have striven,

They battled that we might be free.

We to their living cause are given;

We arm for men that are to be.

Among the nations nobliest chartered,

England recalls her heritage.

In her is that which is not bartered,

Which force can neither quell nor cage.

For her immortal stars are burning

With her the hope that’s never done,

The seed that’s in the Spring’s returning,

The very flower that seeks the sun.

She fights the fraud that feeds desire on

Lies, in a lust to enslave or kill,

The barren creed of blood and iron,

Vampire of Europe’s wasted will …

Endure, O Earth! and thou, awaken,

Purged by this dreadful winnowing-fan,

O wronged, untameable, unshaken

Soul of divinely suffering man.

Movement II (Moderato)

X. To Women

Your hearts are lifted up, your hearts

That have foreknown the utter price.

Your hearts burn upward like a flame

Of splendour and of sacrifice.

For you, you too, to battle go,

Not with the marching drums and cheers

But in the watch of solitude

And through the boundless night of fears.

Swift, swifter than those hawks of war,

Those threatening wings that pulse the air,47

Far as the vanward ranks are set,

You are gone before them, you are there!

And not a shot comes blind with death

And not a stab of steel is pressed

Home, but invisibly it tore

And entered first a woman’s breast.

Amid the thunder of the guns,

The lightnings of the lance and sword Your hope,

your dread, your throbbing pride,

Your infinite passion is outpoured

From hearts that are as one high heart

Withholding naught from doom and bale

Burningly offered up,—to bleed,

To bear, to break, but not to fail!

Movement III (Solenne)

XI. For the Fallen 48

With proud thanksgiving, a mother for her children,

England mourns for her dead across the sea.

Flesh of her flesh they were, spirit of her spirit,

Fallen in the cause of the free.

Solemn the drums thrill: Death august and royal

Sings sorrow up into immortal spheres.

There is music in the midst of desolation

And a glory that shines upon our tears.

They went with songs to the battle, they were young,

Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted,

They fell with their faces to the foe.49

[Stanza written by Binyon especially for Elgar:]

They fought, they were terrible, nought could tame them,

Hunger, nor legions, nor shattering cannonade.

They laughed, they sang their melodies of England,

They fell open-eyed and unafraid.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:50

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

They mingle not with their laughing comrades again;

They sit no more at familiar tables of home;

They have no lot in our labour of the day-time;

They sleep beyond England’s foam.

But where our desires are and our hopes profound,

Felt as a well-spring that is hidden from sight,

To the innermost heart of their own land they are known

As the stars are known to the Night;

As the stars that shall be bright when we are dust

Moving in marches upon the heavenly plain,

As the stars that are starry in the time of our darkness,

To the end, to the end, they remain.

Elgar took his title for The Spirit of England from the opening stanza of “The Fourth of August,” the first of the three poems he selected from Binyon’s book. In this he was probably influenced by the publication of The Spirit of Man, a popular anthology of poetry and philosophy compiled by Robert Bridges (1844–1930), who had been made poet laureate in 1913 following Kipling’s refusal of the post. In his preface, Bridges stated the intention of his volume—to uphold and nourish spirituality among the Allies in the face of “the miseries, the insensate and interminable slaughter, the hate and filth” brought on by the “evil” of Prussian materialism, militarism, and conscious criminality.51 In “The Fourth of August” Binyon associates the “Spirit of England” with qualities such as mettle, courage, ardor, and steadfastness, which, he implies, define the English as individuals, as an army, and as a nation with a noble destiny. Other meanings are also brought into play, however, which remove the poem from its immediate time and place to the realms of the metaphysical and the eschatological: among those who make up the “Spirit of England” are the “glorious dead” who in the battle for freedom have already “gone before” (in both senses of the phrase). Here, as in the Ruskin extract Colvin cited for Elgar, war is presented not only as a fight for good against evil, but as a purgation of the spirit of the English, from whom self-sacrifice is required to secure the cleansing, revivification, and salvation of Europe. Binyon encapsulates this in his image of the winnowing-fan, a tool from which crops are thrown up into the air as the fertile grain is sorted from the lightweight chaff. That this was an attractive metaphor for Elgar is evident in his decision to reprise the opening stanza at the end of the first movement, thereby bringing purged (seventh stanza) and purified (first stanza) into a direct relationship with each other through juxtaposition and reinforcing the interpretation of spirit as soul, that is, along eschatological lines. At its first appearance the word purified falls on a weak beat but is accented, and in its final iteration is given musical expression with a movement sharpwards in the harmonies.

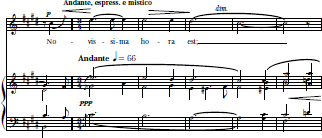

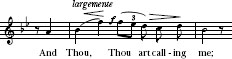

Example 1a. “Novissima hora est” motif, The Dream of Gerontius, Part I, rehearsal no. 66.

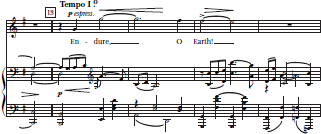

Example 1b. “Endure, O Earth!” The Spirit of England, first movement, “The Fourth of August,” rehearsal no. 13.

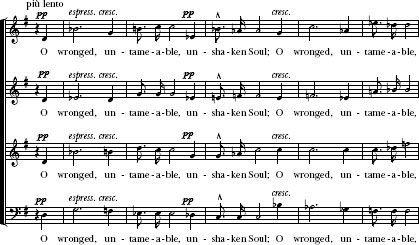

More significant are the motivic links Elgar establishes between this movement and The Dream of Gerontius, connections that confirm a bond between these two works in his imagination. For the phrase “Endure, O Earth!” (seventh stanza), Elgar quotes his setting of the phrase “Novissima hora est” (“This is the final hour”) from Gerontius (compare Examples 1a and 1b), probably prompted by the phrase “hour of peril” in the fourth line of the first stanza, but again focusing attention on the afterlife: this poignant phrase is sung by Gerontius in the final agonies of corporeal death (Part I, rehearsal no. 66), on encountering God (Part II, at “Take me away,” two measures after rehearsal no. 120), and by the Angel of the Agony pleading with Christ for deliverance of the Souls in Purgatory (Part II, at “that glorious home,” five measures before rehearsal no. 113—“Hasten, Lord, their hour, and bid them come to Thee, / To that glorious Home, where they shall ever gaze on Thee”).52 Elgar’s reuse of this distinctive motif here also gives musical utterance to Binyon’s implied parallel between the “Spirit of England” and the figure of Christ in the lines that follow (“O wronged, untameable, unshaken / Soul of divinely suffering man”), for in Gerontius, as Moore points out, the “novissima hora est” motif takes its shape from those associated both with Christ’s peace (“Thou art calling me”) and with the agony of the crucifixion (“in Thine own agony”) (compare Example 1a with 2a and 2b).53 For the closing lines of the seventh stanza, as he did in the opening of Part II of The Dream of Gerontius, Elgar seems to suspend time, delivering the direct address in a hushed, unaccompanied chorale, markedpiú lento and espressivo:

Example 2a. “Christ’s Peace” motif, The Dream of Gerontius, Part I, five measures after rehearsal no. 22.

Example 2b. “Christ’s Agony” motif, The Dream of Gerontius, five measures after rehearsal no. 62.

Example 3. The Spirit of England, first movement, “The Fourth of August,” rehearsal no. 14.

The “Novissima hora est” motif also resurfaces in the second movement, “To Women,” where it is heard (over the “Spirit of England” theme from the first movement) in the solo part and taken up by the chorus at “but not to fail!” (Example 4).54 For added emphasis, the melody used for “this dreadful winnowing-fan” in the previous movement is alluded to in the violins in the measure before rehearsal no. 11, where the chorus reenters with “to bleed, to bear, to break.” Once again the connections with Christ are significant, emphasizing both divine sacrifice and endurance, for the text of this movement can be interpreted as a latter-day Stabat Mater Dolorosa. As mothers, but also wives and lovers, women of England witness in spirit the corporeal suffering and death of their men on the battlefield, just as Mary stood weeping for her Son at the foot of the Cross on Golgotha. Binyon’s choice of language seems to echo the opening verses of the thirteenth-Century Latin hymn, particularly in his fifth and sixth stanzas that refer to the “infinite passion,” seemingly anachronistically to “lance and sword,” and to the scourging of Christ with the phrase “to bleed, to bear, to break.” (Here Elgar links the motif of endurance with immortality by anticipating in the orchestra the climax of the third movement, the ghostly legion “moving in marches upon the heavenly plain,” as well as “Flesh of her flesh they were, spirit of her spirit” and “There is music in the midst of desolation.”)55 The connection is lost for us, however, in his association of “passion” with “throbbing pride.” Elgar’s biographer Basil Maine heard further echoes of The Dream of Gerontius in this movement:

At more than one point in this deeply moving music but especially in the brief orchestral passage at the end, the spirit that pervaded the “Angel of the Agony” episode in “Gerontius” is perceptibly at work.56

Example 4. The Spirit of England, second movement, “To Women,” rehearsal no. 10.

The chromaticism and the repeated rhythm (short-long) forge this link, which again transports us to Calvary and an invocation to the crucified Christ; for as Gerontius is told just before the appearance of this heavenly being, the Angel of the Agony is “the same who strengthened Him, what time He knelt / Lone in the garden shade, bedewed with blood. / That Angel best can plead with Him for all / Tormented souls, the dying and the dead.”

A further motivic link with Gerontius is established in the first movement for the sixth stanza (rehearsal nos. 9–13), which culminates in the line “Vampire of Europe’s wasted will.” At this point Elgar quotes the Demons’ Chorus from the second part of the oratorio, thus connecting implicitly the architects of the Prussian war machine with the depraved beings who howl and snatch at the soul of Gerontius as it passes on its way to Judgment. On June 17, 1917, after completing The Spirit of England, Elgar sent an explanation of this decision to Ernest Newman, who was to write an account of this movement for the Musical Times:

Do not dwell upon the Demons part:—two years ago I held over that section hoping that some trace of manly spirit would shew itself in the direction of German affairs: that hope is gone forever & the Hun is branded as less than a beast for very many generations: so I wd. not invent anything low & bestial enough to illustrate the one stanza; the Cardinal invented (invented as far as I know) the particular hell in Gerontius where the great intellects gibber & snarl knowing they have fallen:

This is exactly the case with the Germans now;—the music was to hand & I have sparingly used it. A lunatic asylum is, after the first shock, not entirely sad; so few of the patients are aware of the strangeness of their situation; most of them are placid and foolishly calm; but the horror of the fallen intellect—knowing what it once was & knowing what it has become—is beyond words frightful.57

The words “held over” in this letter have often been interpreted to mean that Elgar had difficulty composing this passage—that with his style so firmly rooted in the Austro-German tradition, he struggled to position the Hun musically as the “Other,” in a way he had not in his depiction of the “otherness” of the Mogul emperors for the Crown of India three years earlier—and that it had taken him well over a year to arrive at this solution.58 If this was indeed a troublesome passage that held up the completion of the work for so long, however, it seems odd that among the sketches so few are devoted to this particular section.59 A more plausible explanation is that Elgar arrived at his solution early on, and held this particular movement back—the first performances (from May 3, 1916, until the premiere of the completed trilogy on October 4, 1917) were of the second and third movements. His reasons for this decision were probably twofold. First, he would have wanted to avoid offending certain friends, most notably Edgar Speyer, the wealthy patron of London’s transport system, hospitals, and concert life. Despite having English nationality, the Speyer family had rapidly become the target of anti-German harassment in the early months of the war: Edgar Speyer was ostracized by former associates, accused of collusion with the enemy, and pressured to relinquish his baronetcy and membership in the Privy Council. Ultimately, on May 26, 1915, Speyer and his family left England for the United States. Elgar had been supportive under these difficult circumstances and might well have remained reluctant to place “The Fourth of August” before the public until the Speyers had settled abroad.60 Elgar’s great German musical ally, the conductor Hans Richter, was dead by the end of December 1916.

From Alice Elgar’s diaries we know that German forces were frequently described as demonic and brutal in the Elgar household during the early stages of the Binyon project. On December 31, 1914, she wrote, “Year ends in great anxieties but with invaluable consciousness that England has a great, holy Cause—May God keep her,” and from Severn House the following month she recorded outright condemnation of the latest Zeppelin activity:

[19 January 1915:] Seemingly tranquil but at night a German air raid on Yarmouth & that part of East Coast. They damaged houses & caused some loss of life, engulfing themselves more deeply in crime than ever. Brutes—

[20 January 1915:] Long accounts of air raid. Hope it has shown the U.S.A. what lengths uncivilised fiends will go

[27 January 1915:] Splendid accounts of naval action. Must have immense moral effect—No truth in the elaborate German lies. Almost impossible to conceive that their airships dropped bombs on the sailors while they were trying to save German drowning men—Demons might have acted better.61

This intemperate language resurfaced twelve months into the war, when Alice, who had ambitions as a versifier, tried her hand at a war sonnet after Binyon for publication in The Bookman. The Handel scholar R. A. Streatfeild, acting as go-between for the editor, advised her that he would “(probably) suggest another adjective in the place of ‘devilish,’” but the original word was retained when the poem went into print.

England. August 4, 1914. A retrospect.

Holding her reign in kindly state and might,

Still deeming honour trod in knightly ways,

Half armed, lay England, through the summer days;

Her rule, outspeeding dawn, outchecking night,

Welded the sphere in wide, majestic flight.

When lo! a foe appears who neither stays

Nor warns, but sweeps the Belgian plains and sways

Grim hosts and arrogates a devilish right. ‘

England still sleeps,’ he said ‘and dreams of gain,

She will not stir, who once was battle’s lord,

Or risk the clash of squadrons on the main;

Her treaties may be torn, while ‘gainst the horde

These lesser folk may plea[d]e for help in vain …’

Then, throned amidst the seas, She bared her sword.62

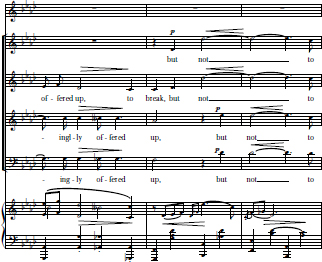

Such rhetoric is a reflection of the propaganda that was disseminated widely in the early months of 1915, particularly concerning alleged German atrocities in Belgium, which were detailed in the Bryce report, published in May 1915.63 Characterization of the German army as a demonic horde was encouraged in response to the use of poison gas and flame throwers against Allied combatants, air raids that resulted in civilian casualties, and incidents such as the torpedoing of the British passenger liner Lusitania and the “martyrdom” of nurse Edith Cavell, all of which were dwelt on at length by the British press in horror and outrage (see figure 2).64

For Elgar, however, setting the sixth stanza of “The Fourth of August” to the music he had hitherto used for Newman’s demons was not an exercise in cheap propaganda, but part of his conception of the war as a metaphysical struggle between hell and heaven, of darkness and light, for the soul of humanity. Concern that he should not be seen to be peddling anti-German propaganda, fueling popular hatred, and endorsing simplistic views of the war as a conflict between English knights and German devils, might well have been a second factor in his decision to suppress the first movement for so long. And on this point Elgar’s dialogue with the critics is revealing.

Figure 2. “The Murder of Nurse Cavell,” The War Illustrated: A Picture-Record of Events by Land, Sea and Air (30 October 1915). Reproduced by permission of the British Library.

In April 1916, Ernest Newman wrote an article on The Spirit of England for The Musical Times in anticipation of the premiere of the second and third movements, which was scheduled for the following month (described in greater detail below). In his essay, Newman extemporized on material Elgar had supplied for that purpose in a personal letter, but the critic also indulged in explicit anti-German sentiments couched in “holy war” rhetoric:65

We gladly leave the writing of Hymns of Hate to the race that has shown us in too many other respects also how near its instincts are to those of the barbarian. An older and better civilisation looks to its leading artists for something different from the German froth and foam, bellowing and swagger. We are not “too proud to fight,” but we are too proud to abase our emotions about the war to the level of those of our bestial foe; to do that would be disloyalty to the memory of our holy dead.66

These references to “Hymns of Hate,” which incensed Newman so deeply, allude to settings of a poem penned in 1914 by a German-Jewish writer, Ernst Lissauer, which had been used to whip up a fury of Anglophobia throughout Germany in the early months of the war. It was from this that the German army derived the slogan “Gott strafe England” (God punish England), for, as Stefan Zweig recalled, Lissauer’s poem had “exploded like a bomb in a munitions factory”:

The Kaiser was enraptured and bestowed the Order of the Red Eagle upon Lissauer, the poem was reprinted in all the newspapers, teachers read it out loud to the children in school, officers at the front read it to their soldiers, until everyone knew the litany of hate by heart. As if that were not enough, the little poem was set to music and, arranged for chorus, was sung in the theatres.67

Copies reaching England were seized upon by the press, the text appearing in the Times on October 29, 1914 (in a translation prepared by Barbara Henderson for the New York Times), and a musical setting (attributed to Franz Mayerhoff) in the Weekly Dispatch of March 7, 1915. This stoked anti-German hatred in turn, triggering a series of musical retorts, particularly from the music halls: Whit Cunliffe, for example, popularized Robert IP Weston and Bert Lee’s Strafe’emf; Thomas Case Sterndale Bennett produced My Hymn of Hate; and a lesser-known composer, Harold Whitehall, composed a Tyneside Hymn of Hate.68 A satirical rendition of Lissauer’s “Hymn” in its musical raiment was given on March 15, 1915, at the Royal College of Music by Hubert Parry, Walter Parratt, and an impromptu choir: “Sir Walter asked them to sing the hymn with plenty of snarl, to express honestly the intentions of the composer … but they laughed too much to snarl.” Later burlesque performances included those by Major Mackenzie Rogan and the band of the Coldstream Guards in morale-building concerts behind the lines in France and Flanders, on ships, and in munitions factories, with “a second verse punctuated by snatches of British melodies, patriotic and profane, expressing Tommy’s reply from the trenches to the comminatory bitterness of Prussianism.”69

It was probably reluctance to be seen participating in this venomous exchange that prompted Elgar’s exhortation to Newman not to “dwell upon the Demons part” when writing his introductory article about the first movement for the Musical Times a year later.70 Although Newman took care to distinguish Elgar’s Spirit of England from “the strut and swagger of the commoner ‘patriotic’ verse and music” in this essay, “the foul thing” that Germany had become was still to be roundly denounced: “For the first time in the lives of many of us we find ourselves indulging in a national hatred and not seeing any reason to be ashamed of it,” he declared, for “even Fafner, Wagner’s last word in brutishness, would not have decorated himself with a Lusitania medal.”71 Despite Elgar’s instruction, Newman emphasized the “Demons part,” predicting:

We shall henceforth listen to the Demons’ Chorus with a new imagery flashing across our minds… . We shall have a new appreciation of the “con derisione” that Elgar, with a prophetic intuition, has written in the score of “Gerontius” over the reiterated “gods” [musical example inserted here]—And at the end of it all the Demons’ theme, as in the oratorio, goes panting and growling into the depths of hell.72

Other critics observed a heightened sense of violence in Elgar’s own performances of the “Demon’s Chorus” from Gerontius around this time. Herbert Thompson, reviewing for the Yorkshire Post a Leeds Choral Union performance of The Dream of Gerontius (programmed alongside The Spirit of England, complete) under Elgar’s baton on October 31, 1917, noted, “The only thing that jarred was the nasal tone in the Demons’ chorus, which was so exaggerated that it ceased to be impressive, and was merely grotesque”; moreover, the critic records that he had begun to notice an increasing cynicism in Elgar’s delivery of this passage at least six months earlier.73 In his response to The Spirit of England, however, Thompson made a point of trying to rescue “The Fourth of August” from the taint of anti-German propaganda, as his comments on the premiere of the complete work, conducted in Birmingham by Appleby Matthews, suggest:

The general character of the poems by Lawrence Benyon [sic], which Sir Edward Elgar has chosen to set, is that of patriotism, which rings true, the more so since it is utterly devoid of vulgar bluster, and is dignified and restrained in sentiment… . There is a touch of indignation in an outburst concerning the barren creed of blood and iron, but there is no indication of any futile and childish “Hymn of Hate,” either in the verse or in the music, which never loses control or degenerates into mere abuse.74

Elgar’s own words on the subject in his June 1917 letter to Newman, give us a sense of how his thinking on the war had changed over the three years since his 1914 comment to Schuster (yet another of Elgar’s friends with German origins), quoted above, and a year after the catastrophe of the Somme. It is the imagery of the madhouse that now seems most eloquent to him, of which he had had firsthand experience as a young man, providing musical distractions to inmates of Powick Lunatic Asylum. The careful distinctions he draws between the innocent, the obliviously mad, and the knowingly corrupt and depraved is a telling one, as is the image of the remnants of noble souls overtaken by demons who, by implication, respect no national boundaries. In this the composer echoed sentiments expressed on the debasement of German culture in another of Binyon’s poems from The Winnowing-Fan, the seventh, titled “To Goethe.”75 But Elgar also mirrors the thoughts of another writer with whom he is not so readily associated—H. G. Wells (1866–1946), who had delivered the following statement in his pamphlet The War That Will End War, issued in August 1914:76

We are fighting Germany. But we are fighting without any hatred of the German people. We do not intend to destroy either their freedom or their unity. But we have to destroy an evil system of government and the mental and material corruption that has got hold of the German imagination and taken possession of German life… . This is already the vastest war in history. It is war not of nations, but of mankind. It is a war to exorcise a world madness and end an age.77

That Elgar shared Wells’s vision of an impending Armageddon brought on by the materialism and corruption of those who would cast themselves as gods, and requiring the sacrifice of heroes, is further suggested by his song “Fight for Right” (London, Elkin, 1916)—a setting of Brynhild’s words on sending Sigurd off to deeds of glory in William Morris’s epic poem The Story of Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niblungs (1876), which was based on the same sources as Wagner’s Gbtterdammerung.78

Elgar had The Dream of Gerontius almost constantly in mind through the early years of the war. On September 8, 1914, Alice wrote in her diary, “It wd. have been ‘Gerontius’ tonight at Worcester Fest[ival]—but for Hun Kaiser”; and on November 19, Charles Mott sang the “Proficiscere” from Gerontius during an organ recital at Worcester in memory of Lord Roberts, colonel in chief of the empire troops in France, who had succumbed to pneumonia while visiting Indian soldiers at St. Omer. Elgar could not attend the recital, but approved organist Ivor Atkins’s “excellent choice.”79 In February the following year, just after Elgar had begun work on the Binyon settings, Alice noted that he met with Clara Butt “to go through Gerontius” in preparation for her first performance of it at the Royal Albert Hall on the twenty-seventh of that month, in the role of the Guardian Angel.80 In March 1916, he and Alice met again with Clara Butt, this time to plan what would become one of the most extraordinary musical events of the war.81 At a time when “music-making on a large scale had almost completely ceased,” as Basil Maine recalled, and nocturnal transportation around London was restricted and hazardous due to the blackout, Butt’s plan was to present a week of six consecutive oratorio performances at the Queen’s Hall (preceded by two performances in Leeds and Bradford respectively) of The Dream of Gerontius and the second and third movements of The Spirit of England (their initial performances) to raise funds for the Red Cross and Order of St. John of Jerusalem in England.82 The London performances took place in the week of May 8–13, 1916, with John Booth and Agnes Nicholls taking the solo parts in “To Women” and “For the Fallen” respectively, and Clara Butt herself taking the Guardian Angel in Gerontius.

The success of these performances was remarkable. King George V, Queen Mary, and Queen Alexandra attended twice, and in total the week of performances netted the then considerable sum of £2,707.83 In a letter to Lady Elgar, R. A. Streatfeild described the Thursday night performance as “wonderful & unforgettable … I still feel as if I were vibrating all over.”84 For Elgar, this must have been an overwhelming experience. His Dream of Gerontius was almost certainly given in its original form (that is, not the bowdlerized version produced for performance in a consecrated Anglican space) at these concerts. With the first movement of The Spirit of England, “The Fourth of August,” still unfinished, he must have been greatly encouraged by the reception accorded his interpretations of the Binyon poems, not least by the publicity put out by Clara Butt for these performances, the main points of which were summarized as follows by her authorized biographer:

She had other motives in mind in this unusual enterprise besides the obvious ones of raising money for a patriotic cause. She had a religious motive as well. She felt it was time that the people who were passing through the sorrows and anxieties of war should hear music that was definitely spiritual, and that English art should try to express the attitude of the English mind to the life after death.

She determined to challenge London with something really beautiful and mystic. “We are a nation in mourning,” she said, discussing the project. “In this tremendous upheaval, when youth is dying for us, I want to give the people a week of beautiful thoughts, for I am convinced that no nation can be great that is not truly religious. I believe that the War has given us a new attitude towards death, that many who had no faith before are now hungering to believe that after death there is life.”85

Though the first movement of The Spirit of England—the most explicit in its connections with The Dream of Gerontius—was not heard at these performances, the combination of Gerontius, “To Women,” and “For the Fallen” was a powerful one, as a letter written to Elgar by Sidney Colvin’s wife, Frances, after the Monday afternoon performance confirms:

How can I ever tell you dear Edward what we felt today or how deeply moved we both were—it is all quite wonderful & just what one wants at this time—& at all times—it will live always—“For the Fallen” especially will always be the one great inspiration of the War. My heart is full of warm gratitude to you—but my eyes are sore with tears and I can’t write—but we both send you our heartfelt love and congratulations—Bless you… . How lovely the choir was! Sidney has a bad cold but nothing would have kept him from going.86

These Red Cross concerts fused The Spirit of England with Gerontius in the public imagination, forming the two works into a diptych that provided a communal focus for grief and prayer and assumed a quasi-liturgical function. As Maine relates:

The music of “Gerontius,” during that week in the spring of 1916, shone with a new significance and became a symbol of intercession; while in “The Spirit of England” was seen, transfigured, the face of human suffering, and there was as yet no sign of disillusion in that face—not yet had the broken songs of the soldier-poets been heard.87

Clara Butt’s claim that death and the future life were among the most pressing issues thrown up by the war matched the perceptions of Anglican clergy, of whom “Is it well with the fallen?” had become one of the most frequently asked theological questions both by laity on the home front and among the troops at the western front.88 For many, the attempts by the national Church to meet the complex spiritual needs of the people were found wanting. Despite individual acts of extraordinary heroism, Anglican chaplains were deemed to be less than fully prepared for their ministry at the front: it was the Roman Catholic padres who earned a reputation for supreme courage, risking their lives to administer extreme unction to the dying while the Anglican clergy, initially at least, were commanded to stay behind the lines and generally did as they were told, without demur. For at least one soldier, confession and absolution meant that “the Church of Rome sent a man into action mentally and spiritually cleansed,” and thus prepared for death, whereas “the Church of England could only offer you a cigarette.”89 In almost two years of war, the violent and premature deaths of so many young men overseas, whose bodies and personal effects were often irrecoverable by their grieving families, rendered traditional mourning practices and rituals irrelevant, inadequate, or impossible. At home, ostentatious expressions of grief by relatives were discouraged as unpatriotic, as was the placing of memorial plaques in churches until after the war for fear of lowering morale. The result was widespread, chronic, and unresolved grief among those “left behind,” for which release was craved no matter how temporary or what conventional or unconventional guise it might take.90 In these extreme, highly charged times, the harder lines of British Protestantism gradually softened in a variety of directions—toward Catholicism, spiritualism, and an evolving ecumenism.91 Public prayer for the departed, for example, still stigmatized by the abuses of the medieval chantry system, had not commonly been a part of Anglican worship in 1914, but by 1917 the demand for such orisons had persuaded the Archbishop of Canterbury to produce a new Form of Prayers, including a discretionary prayer for the dead; even then, one or two of his bishops protested that such prayers were contrary to scripture and Anglican teachings.92 Anglo-Catholics welcomed this shift in the Church’s position, openly offering requiems and issuing cards that bore the portraits of soldiers for whom the requiem was to be given.93 In this context the early discussion of plans for a temporary monument to the dead in Whitehall is revealing: initially Lloyd George’s idea was to build a “catafalque … past which the troops would march and salute the dead”; Lord Curzon, however, considered this “more essentially suitable to the Latin temperament.” Lutyens was finally instructed to produce a nondenominational structure, and it was his suggestion that the name be changed from catafalque to cenotaph, meaning “empty tomb” and implying resurrection, but pointedly avoiding association with the Latin mass for the dead.94

For musically aware listeners of the time, references to the motifs from Gerontius associated with “Christ’s Peace” and “Christ’s Agony” that run through The Spirit of England articulated a further meaningful theme for those at the front and at home. A British soldier was called upon to sacrifice himself for the greater good (to be willing to kill and be killed), but also, for some, to atone for a sense of national sin—the selfish materialism, disunity, and moral dissipation of the older generations. Binyon hints at this in the second stanza, line 3, of “The Fourth of August.” Similarly, the protagonist of H. G. Wells’s wartime novel, Mr. Britling Sees It Through (1916), is haunted by the notion of “redemption by the shedding of blood” once war becomes a reality.95 Wells describes Mr. Britling musing on a few such home truths—among them the complacency of the British government before the war—in the opening scenes of this semiautobiographical novel:

Not only was [Mr. Britling] a pampered, undisciplined sort of human being; he was living in a pampered, undisciplined sort of community. The two things went together… . This confounded Irish business, one could laugh at it in the daylight, but was it indeed a thing to laugh at? We were drifting lazily towards a real disaster. We had a government that seemed guided by the principles of Mr. Micawber, and adopted for its watchword “Wait and see.” For months now this trouble had grown more threatening. Suppose presently that civil war broke out in Ireland! Suppose presently that these irritated, mishandled suffragettes did some desperate irreconcilable thing, assassinated for example! That bomb in Westminster Abbey the other day might have killed a dozen people… . Suppose the smouldering criticism of British rule in India and Egypt were fanned by administrative indiscretions into a flame.96

If the mass shedding of blood was a catharsis by which the nation would be united and cleansed, individual redemption and collective redemption were thus intertwined, inviting parallels between the heroism of the most low-born Tommy in the trenches and the atonement vouchsafed to Christians through the Blood of Christ. At the front British Protestants were brought into a relationship with Catholic imagery and culture such as most had probably never known. Fighting in a Catholic country and often alongside Catholic comrades, they came across roadside shrines in every village—crucifixes, calvaries, madonnas, and saints—that would sometimes assume a symbolic value according to the extent to which they had been spared or suffered shell damage.97 Amid the carnage and desolation of the trenches, such symbolism encouraged a powerful identification with the sufferings of Christ, both for the soldier at the front—as a fellow sufferer probably more than as a savior—and for his relatives at home looking for consolation. The poetry of the trenches is full of references to Christ, as in “The Redeemer” from Siegfried Sassoon’s The Old Huntsman and Other Poems. In the rain-sodden night, the speaker struggles along a ditch with his company; in the burst of a shell he looks back at his comrade and sees a vision of Christ laboring under the cross. The merging of the two images implies a connection of pain, endurance, and unprotesting self-sacrifice suffered by one extraordinary but ordinary man for the redemption of others: “But to the end, unjudging, he’ll endure / Horror and pain, not uncontent to die / That Lancaster on Lune may stand secure.”98 After the war, this idea would also find expression in Stanley Spencer’s canvas The Resurrection of the Soldiers at the Oratory of All Souls, Sandham Memorial Chapel (Burghclere, Hampshire), which drew on the artist’s own experiences of action at Salonica. Here the viewer is literally overwhelmed by images of the cross, as soldiers emerge from the ground, dusting themselves down and shaking hands with resurrected comrades, and present their crosses to the figure of Jesus in the middle distance. Lying on the side of a collapsed wagon, a single soldier ponders the figure of Christ on a crucifix.99

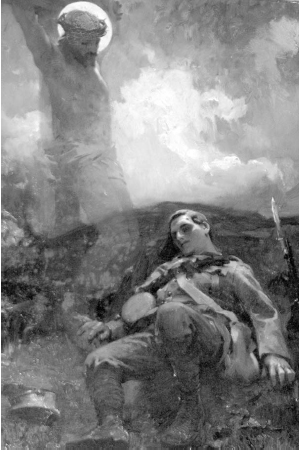

Relatives of combatants found comfort in images of Christ on the battlefield, which not only seemed to confirm the nobility and holiness of the cause, but also, if death was to be the fate of their loved ones, the promise of redemption by self-sacrifice. One of the most popular images of consolation, one with strong Catholic overtones, was a colored print taken from an oil painting commissioned for the Christmas 1914 edition of The Graphic, titled Duty or The Great Sacrifice (see figure 3). The artist, James Clark, depicts a young soldier lying dead from a head wound on the battlefield (“sacrificed on the altar of duty to country”), his hand touching the feet of a spectral Christ, haloed by the sun, who seems to gaze down in recognition from the cross. This print was circulated across the country, endorsed by at least five of the nation’s bishops, and further copies of this, dubbed the “most inspired Picture of the War,” were offered for sale in The Graphic of February 6, 1915.100 It could be found hanging in churches, Sunday Schools, soldiers’ institutes, public halls, classrooms, and private houses, and after the war it was used in several places as a design for stained-glass memorial windows.101 The print was so ubiquitous it is difficult to imagine that Elgar and his associates were unaware of it, just as the mass rallies and jingoistic speeches of the charismatic Anglican bishop of London, Arthur Foley Winnington-Ingram (1858–1946)—born in Worcestershire, like Elgar—must also have entered their consciousness at some level. Christ was often in the bishop’s sights, and he often spoke of the war as a struggle between “Christ and Odin,” “Berlin against Bethlehem,” or of “the Nailed Hand and the Iron Fist.”102 Sometimes delivered in his uniform as chaplain to the London rifle brigade, and from a truck swathed in Union Jacks or an altar of drums, his fervent, imperialist sermons did much to alienate his countrymen, particularly in the months following the Somme; but throughout the war years his message was simple and unswerving, as in this example, speaking of bereaved parents who had visited him for succor in Advent 1916:

Figure 3. James Clark, Duty, also known as The Great Sacrifice, oil on canvas, 1914. Donated by Clark to the Royal Academy’s War Relief Exhibition on January 8, 1915, it was bought by Queen Mary, who gave it to Princess Beatrice in memory of her son Prince Maurice Battenberg who had died at Ypres in 1914. Beatrice presented it to St. Mildred’s Church, Whippingham, Isle of Wight, where it now hangs in the Battenberg Chapel. Photo Rachel Cowgill.

The precious blood of their dearest boy mingles with the Precious Blood which flowed in Calvary; again the world is being redeemed by precious blood. “CHRIST did what my boy did; my boy imitated what CHRIST did” they say.103

The presence of the motifs associated with Christ from The Dream of Gerontius in The Spirit of England does not imply that Elgar shared the bishop’s starry-eyed jingoism. Daniel M. Grimley has noted how Elgar repeatedly undercuts even his most powerful and assertive moments of uplifting nobility in The Spirit of England, particularly in the final movement, “For the Fallen.” The resulting atmosphere of uncertainty, melancholy reflection, and vulnerability is intensified by several striking features: the return to the opening material of “For the Fallen” in the closing moments; the movement’s harmonic circularity, the putatively aspiring semitonal ascent in the overall tonal scheme of the trilogy (G, A-flat major/minor, and A minor); and particularly by the pensive rocking between A major and A minor in the final bars, marked morendo. With a passing reference to Catholic doctrine concerning the afterlife, Grimley observes:

Elgar’s music therefore suggests a state of musical, as well as spiritual purgatory. In Elgar’s setting, Binyon’s words “At the going down of the sun and in the morning / We will remember them” become an anguished expression of longing for closure or death, and not merely a patriotic act of remembrance. Far from being a moment of consolation, it is the most troubled music in the whole work.104

It was this profound emotional complexity that made The Spirit of England such a powerful work expressing a righteous idealism tempered by grief and attrition as the war dragged on. H. G. Wells concludes his 1916 novel with an ambiguity that echoes Elgar’s final measures. Adopting the persona of Mr. Britling, whose only son is killed in action, the author works through his emotional and rational responses to the war toward a declaration of faith in “our sons who have shown us God”; but the seemingly serene pastoral sunrise with which the novel concludes is tainted by the inevitability of further bloodshed, especially in the chilling final line (“From away towards the church came the sound of an early worker whetting a scythe”).105

Elgar conducted the completed Spirit of England on October 31, 1917, (the eve of All Saints’ Day), along with The Dream of Gerontius, in a Choral Union concert at Leeds Town Hall, and again on November 24 at a Royal Choral Society Concert at the Royal Albert Hall. For twenty years or so afterward, the composer continued to direct cathedral performances of “For the Fallen” at the Three Choirs Festival and, as previously noted, for Armistice Day services and concerts broadcast by the BBC.106 In The Spirit of England Elgar reengaged with eschatological themes familiar from The Dream of Gerontius and his fraught oratorio project that culminated in the abandonment of The Last Judgement—namely, afterlife, purgatory, and redemption. This vein of Roman Catholic doctrine was combined with a reflective and consoling, though ultimately inconclusive message to his fellow countrymen and women tested to extremes in the worst excesses of the war that theirs was a divine cause, and their physical and spiritual suffering necessary for the emergence of a newly purified Europe: “redemption by the shedding of blood.”107 The Catholic elements discussed here are discernible but never brought conspicuously into the foreground, Elgar demonstrating again his ability to explore aspects of his own spirituality in music without disturbing Protestant sensibilities. Indeed, The Spirit of England seems in many ways to anticipate the more ecumenical and internationalist outlook that emerged among Anglicans in the years after the war—a step on the way to John Foulds’s World Requiem (1919–21), dedicated to “the memory of the Dead—a message of consolation to the bereaved of all countries.”108 With its eclectic text, combining passages from the Latin Mass for the Dead, John Bunyan, and the fifteenth-Century Hindu mystic Kabir among others, Foulds’s score was certainly far removed from the traditions of English oratorio prevalent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in which England, through metaphor, is depicted as a Protestant bastion in a sea of decadent and minatory Catholicism.

The contexts in which The Spirit of England were heard over the airwaves in the years after 1918 also seem to point to the future, although it is not always clear how far programming decisions were influenced by Elgar himself. On November 11, 1924, in a BBC concert broadcast from Birmingham, the cantata was heard in the midst of a miscellaneous sequence apparently assembled to create a narrative from mourning to jubilation: the hymn “O God Our Help in Ages Past”; Sullivan’s Overture In Memoriam; Elgar’s The Spirit of England; a “dramatic recital” of poetry by Rupert Brooke; “I Know that My Redeemer Liveth” from Handel’s Messiah; Elgar’s “The Immortal Legions” from his recent Pageant of Empire music; as well as the first Pomp and Circumstance march.109 In 1925 Elgar conducted the London Wireless Orchestra in the introspective third movement of his First Symphony and the “Meditation” from his Lux Christi (an instrumental interlude from Elgar’s first oratorio that is saturated with themes associated with Christ in that work) as a prelude to the commemoration service at Canterbury Cathedral; this was followed immediately by the complete Spirit of England, and later in the evening by the first and second Pomp and Circumstance marches.110 And Elgar’s Enigma Variations, op. 36, and “For the Fallen” concluded the radio program In Memoriam 1914–1918: A Chronicle, compiled by E. A. Harding and Val Gielgud, and broadcast from all BBC stations on Armistice Day evening in 1932. Poetry reading formed the main part of this program, which combined the voices of soldier and noncombatant poets alike, in a selection drawn from John Masefield, Rupert Brooke, Herbert Asquith, Laurence Binyon, Julian Grenfell, Alan Seeger, Wilfrid Gibson, William Noel Hodgson, Edward Shanks, Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, Wilfred Owen, Richard Aldington, Lord Dunsany, and Thomas Hardy.111 One can only wonder what sort of impact these events might have had on the young Benjamin Britten—then a schoolboy—and how much, if anything, he may have later recalled of such broadcasts as he began to interleave texts drawn from the requiem mass with poems by Wilfred Owen, preparing to commemorate the dead of another war in his War Requiem of 1961 for Coventry Cathedral.112

NOTES

My thanks to the Arts and Humanities Research Council (United Kingdom) for supporting part of this research, and to the staffs of the Elgar Birthplace Museum; Brotherton Library Special Collections (University of Leeds); British Library; BBC Written Archives; and St. Mildred’s Church, Whippingham, Isle of Wight for their assistance. I am grateful to Byron Adams, Charles Edward McGuire, Derek Scott, and Aidan J. Thomson for generous suggestions and comments on an early version of this essay read as a paper at the Second Biennial Conference of the North American British Music Studies Association, August 2006, as well as to Julian Rushton for his thoughts at various stages of the project.

1. Epigraph: H. G. Wells, The War That Will End War (London: Frank & Cecil Palmer, 1914), repr. in W. Warren Wagar, ed., H. G. Wells: Journalism and Prophecy, 1893–1946 (London: Bodley Head, 1965), 57.

2. Richards argues that The Dream of Gerontius “may not be a directly imperial work, but it contains something of the spirit of Elgar’s Empire, the idea of Empire as a vehicle for struggle and sacrifice.” Jeffrey Richards, Imperialism and Music: Britain, 1876–1953 (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2001), 60–61.

3. W. H. Reed completely ruled out discussion of Elgar’s faith in his memoir, Elgar as I Knew Him (London: Victor Gollancz, 1936). Though acknowledging the “very strong trait” of “mysticism” that “came out in all [Elgar] did, and of course found its way into his music,” Reed declared this “is no place to discuss creeds or religions, or what he believed and what he did not.” Citing the third movement of Spirit of England and a secular partsong of 1909, he continued, “[Elgar] has more of that quality which we call—for want of a better word—spirituality than perhaps any other composer. One can open the pages of almost any of his works—oratorios, symphonies, or short works like “For the Fallen” or “Go, Song of Mine” [op. 57]—to find this quality evident and unmistakable” (138–39).

4. See Byron Adams, “Elgar’s Later Oratorios: Roman Catholicism, Decadence and the Wagnerian Dialectic of Shame and Grace,” and John Butt, “Roman Catholicism and Being Musically English: Elgar’s Church and Organ Music,” in The Cambridge Companion to Elgar, ed. Daniel M. Grimley and Julian Rushton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 81–105; 106–19.

5. Jerrold Northrop Moore, Spirit of England: Edward Elgar in His World (London: Heinemann, 1984), 56.

6. Ibid., 150.

7. Donald Mitchell, “Some Thoughts on Elgar,” An Elgar Companion, ed. Christopher Redwood (Ashbourne: Sequoia Publishing, 1982), 284. Mitchell’s perception has been reinforced through the recording history of the work: The Spirit of England is often paired with Elgar’s Coronation Ode and packaged with cover art based on images of the British monarchy, billowing Union Jacks, etc. See, for example, the 1985 Chandos recording (CHAN 8430) that reproduces an image of “The King as He Will Appear in Coronation Robes” from a Colman’s Starch trade card issued just before the coronation of Edward VII in 1902 (Mary Evans Picture Library, ref. 10083782).

8. See also Basil Maine’s description of this section, in Elgar: His Life and Works, 2 vols. (London: G. Bell, 1933), 2:239. Maine makes a clear distinction, however, between the tone of The Spirit of England and that of other, imperialist Elgar works: “The conception is grandiose, but not as the ‘Pomp and Circumstance’ Marches are. It moves along with no less splendour, but with a more austere deliberation.”

9. See, for example, Bernard Porter’s summary dismissal of The Spirit of England in “Elgar and Empire: Music, Nationalism and the War,” in Oh, My Horses! Elgar and the Great War, ed. Lewis Foreman (Rickmansworth: Elgar Editions, 2001), 148–49. Porter does concede that the third movement (“For the Fallen,”) “may be thought to compensate for the bitterness (but not the jingoism, still) of the rest.” Porter, “Elgar and Empire: Music Nationalism and the War,” 149.

10. For a detailed discussion of Elgar’s early training as a Catholic, see Charles Edward McGuire’s essay in this volume.

11. Letter from Elgar to Frank Schuster, 25 August 1914, in Edward Elgar: Letters of a Lifetime, ed. Jerrold Northrop Moore, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), 276–77.

12. On the fate of the horses at Mafeking, see Robert Baden-Powell, Lessons from the ‘Varsity’ of Life (London: C. A. Pearson, 1933), 207–9. Robert Anderson also reads Elgar’s remark in the light of the mass mustering of horsepower undertaken by Britain, Russia, Germany, and Austria in the first weeks of August; see Robert Anderson, Elgar and Chivalry (Rickmansworth: Elgar Editions, 2002), 341.

13. Elgar to Schuster, 25 August 1914, Moore, Letters of a Lifetime, 276. Declaring his age (fifty-seven) on a “Householder’s Return” for a Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, Elgar stated, “There is no person in this house qualified to enlist: I will do so if permitted”; quoted in Moore, Letters of a Lifetime, 283.

14. Cammaerts was a geographer by training (via the University of Brussels and Université Nouvelle) and something of “un homme de lettres.” Though Belgian by birth, he was a devout Anglican, and was deeply committed to the Anglo-Belgian Union. He had moved to England in 1908, married the Shakespearean actress Tita Brand, and in 1931 would become professor of Belgian Studies and Institutions at the University of London. Carillon was Elgar’s contribution to an anthology assembled by the novelist Hall Caine to raise funds for the citizens of occupied Belgium, King Albert’s Book: A Tribute to the Belgian King and People from Representative Men and Women Throughout the World (London: Daily Telegraph, Christmas 1914), 84–89. For a summary of Elgar’s activities during the war years, including the periods in which he was working on The Spirit of England, see Andrew Neill, “Elgar’s War: From the Diaries of Lady Elgar, 1914–1918”; and Martin Bird, “An Elgarian Wartime Chronology,” in Foreman, Elgar and the Great War, 3–69; 389–455. On the revision of “Land of Hope and Glory,” see Moore, Letters of a Lifetime (London: Elkin Matthews, 1914), 277–83.