Elgar the Escapist?

MATTHEW RILEY

One of the more serious charges that can be brought against Elgar is that his art is escapist. This criticism can be targeted in several ways. Most obviously, Elgar was committed to a late-Romantic expressive idiom, to overall monotonality (his works usually begin and end in the same key), and to diatonicism as a basic point of tonal reference. These factors meant that during the first two decades of the twentieth century Elgar’s music began to lag behind “progressive” developments in European music. More specifically, some of the literary themes that interested Elgar point to a desire to forget the reality of the present. He embraced the Victorian cult of chivalry and peopled his works with brave knights and heroic kings. As he reached middle age, he wrote music for and about children that echoes a well-known vein of late Victorian and Edwardian literary whimsy (Frances Hodgson Burnett, Kenneth Grahame, J. M. Barrie).1 Finally, in his symphonic works there are moments when Elgar abandons the “musical present” to dwell on thematic reminiscences of earlier movements. At such points the past seems to take on an enchanted quality that the present can never match.

Since Freud, it is common to associate the notion of escape with regression. In this view, to be an escapist means not just to evade adult responsibilities but to suffer from a psychological disorder in which libido is arrested at an infantile stage of development (the “oral” phase). Furthermore, on a cultural level it could be alleged that escapist impulses are easily manipulated (and perhaps originally induced) by commercial or political forces that seek to cement their power and to dilute popular resistance.

But there is another possible perspective. A long tradition of English radicalism links dream, escape, and protest. Victorian medievalists such as A. W. N. Pugin, Thomas Carlyle, Charles Kingsley, and John Ruskin invoked a distant, alluring past in order to focus their passionate concern for the reform of contemporary society. William Morris’s visual designs took inspiration from a medieval world where, he believed, the division of labor was unknown, the worker free. His utopian News from Nowhere (1890) imagined a future, post-revolutionary England steeped in beauty and innocent of money. These escapists wanted to change the world; they held up their dreams and visions as stimuli to action.2 Perhaps the most eloquent plea for the value of escapism was made in the late 1930s by Elgar’s fellow West Midlands Catholic, J. R. R. Tolkien (a direct literary descendant of Morris). In defending his attraction to “fairy stories,” Tolkien warned against confusing the escape of the prisoner with the flight of the deserter: “Just so a Party-spokesman might have labeled departure from the misery of the Führer’s or any other Reich and even criticism of it as treachery.” The companions of “escape,” he explained, are “disgust,” “anger,” “condemnation,” and “revolt.”3

In this light, a reexamination of Elgar’s escapist impulses seems feasible. The present essay sketches an approach to the task. The problem is too large to tackle systematically here: there are too many compositions that could be cited, too many aspects of the late Victorian and Edwardian worlds that are relevant to Elgar’s outlook. Instead, this investigation takes several novel, and perhaps provocative, perspectives on Elgar. The first half examines his personality and attitudes by means of two comparisons. Fiction by Elgar’s contemporary H. G. Wells and historical writings by his friend Hubert Leicester provide lenses through which to view his personal circumstances. They bring into play some sociological issues relevant to Elgar’s escapism concerning class and religion, respectively. The second half of the essay turns to Elgar’s compositions, focusing on his characteristic treatment of sudden tonal shifts and evaluating the specifically musical escapism that becomes possible in his works.

Mr. Polly

H. G. Wells, born nine years after Elgar, was another shopkeeper’s son. His father’s business failed, and he worked his way to national recognition through self-help and hard work. During the first decade of the twentieth century—when Elgar enjoyed his greatest public esteem—Wells wrote three semiautobiographical novels that featured young, lower-middle-class men: Love and Mr. Lewisham (1900), Kipps (1905), and The History of Mr. Polly (1909). In each case the main character is innocent and aspiring but ill educated and trapped in unpromising employment: all the ingredients for escapist behavior are in place.

The character most akin to Elgar is Mr. Polly, whose father owns a music and bicycle shop. Mr. Polly is imprisoned first in the routine of a dull job in a drapery emporium and then in marriage and a High Street shop in Fishbourne in which he foolishly invests some unexpectedly inherited capital. Mr. Polly receives an inferior education and constantly struggles against straightened financial circumstances and meager opportunities for self-improvement. Before his fortunate windfall, he alternates between the shop floor and the employment office. However, he never fully loses his sparks of imagination and wonder. Deep inside him there lurks the conviction that “there was beauty, there was delight; that somewhere—magically inaccessible perhaps, but still somewhere—were pure and easy and joyous states of body and mind.”4 Mr. Polly therefore lives out a dual existence. He avidly collects books, and he prefers to lose himself in them than look after his shop properly. He is a keen cyclist, and at weekends goes on long rides to explore the countryside. His reading is totally unsystematic (and in this respect probably more like Elgar’s than the latter would have admitted), mixing classics (Shakespeare, Boccaccio, Rabelais) with modern adventure stories and thrillers.5 He falls in love in courtly fashion, after the manner of a character in a chivalric romance. As an autodidact, Mr. Polly is uncertain of the pronunciation of words he has seen only in print, but is enthusiastic in devising ringing phrases and sometimes ridiculous neologisms. He has a tendency to verbal pretence, but is also vulnerable to the conversational faux pas.

Mr. Polly suffers from chronic indigestion—of mind as well as body—and thus frequent bouts of bad temper. These afflictions are the result of the impossible conditions that English society imposes on him. The novel begins with Mr. Polly sitting on a stile in a field, with an aching stomach. After fifteen years of unrewarding shopkeeping, he finds his business on the verge of bankruptcy. He is in his mid- or late thirties (the age at which Elgar was still a frustrated provincial violin teacher, seemingly destined for permanent obscurity). Mr. Polly decides to burn the shop and kill himself, allowing his wife to live off the insurance payment. He goes through with the arson, but somehow forgets to execute the suicide. So he pockets a share of the money and abandons his former existence to become a cheerful vagabond, wandering the woods and lanes of southern England. By the end of the novel he is fortunate enough to settle into a job at a country inn, where he enjoys an idyllic existence as a ferryman on a river and works for the comfortable fat woman who owns the establishment. Here he feels “mellowish and warmish.” His existence is “as safe and enclosed and fearless as a child that has still to be born.”6 So Mr. Polly, who was all along an “artless child of nature,” escapes to a womblike refuge.

Elgar, living in the real world, never achieved such a decisive and successful escape. His indigestion of the mind—and tendency to dyspeptic outbursts and theatrical displays of self-pity—remained to the end of his life. Many of the illnesses he suffered during his thirties and forties may well have been at least partly psychosomatic. The early scars left by the Victorian class system made him ashamed of his origins and profession, resentful of establishment “insiders,” but also, conversely, left him afflicted by an unattractive snobbery, overvaluing material possessions, and affecting the behavior of a leisured amateur. His father’s music shop was not especially profitable, nor were Elgar’s teaching rounds, which in any case he loathed. Even in later years, when he had secured a national reputation, he constantly feared having to fall back on teaching or worse. He frequently contemplated suicide—or claimed to—but never attempted the deed. Like Mr. Polly, Elgar had a small slice of financial luck—in his case it was his wife’s (relatively modest) income—but his attempt to develop a career in London between 1889 and 1891 failed, and he was forced to return to his provincial origins and renew his old connections. During the 1890s, his prospects often seemed bleak. One day early in that decade, when he was in his mid-thirties, Elgar, in “a pitifully overwrought state,” explained his troubles to his friend Rosa Burley, the headmistress of the school where he taught the violin. She described his account as “an outpouring of misery that was positively heartrending.”7 The theme was Elgar’s high artistic ambitions, which, he maintained, were constantly thwarted by poverty and the drudgery of his daily job.

Clearly Mr. Polly lags some way behind Elgar both in creative imagination and in artistic, social, and sartorial pretension. But in other respects the two appear rather disconcertingly alike. Elgar was largely self-taught and always carried with him the anxieties of the autodidact. As a young man he immersed himself in books and acquired a taste for chivalry and romance. Later he became a book collector and dabbled on the fringes of literary scholarship.8 His letters display an enduring delight in wordplay. He claimed to have preserved into adulthood a childlike sense of wonder and imagination within himself. Above all he was devoted to the countryside and to cycling, and took every opportunity to lose himself far from civilization.

Nevertheless, despite these parallels in their characters, the differences between the respective destinies of Elgar and Mr. Polly are stark. Mr. Polly discovers that “if the world does not please you you can change it.”9 Wells’s novel thus describes the successful transformation of Mr. Polly’s life. Like Wells, whose portrait of Mr. Polly drew upon his own life experience, Elgar transgressed the hidebound class divisions of the time to become a famous and honored artist. Thus for Elgar the rural idyll remains a temporary refuge; he must always return to society to find a home, make a living, and, of course, make music. Elgar never conducted an incendiary experiment to match Mr. Polly’s burning of his shop, for Elgar harbored ambitions for self-advancement more like those of Wells himself than the quietist solution embraced by Mr. Polly.10 Aside from Elgar’s obvious responsibilities as a father and husband, there was probably too much conservativism in his character, both politically and personally, for him to make a sharp break and abandon his aspirations to respectability and public approval. Guided by his wife, in the 1890s Elgar attempted to escape his difficulties through the alternative methods of hard work, social climbing, and eventually the cultivation of royal patronage, but this deepened his entanglement in English society and, in the end, did not cure his mental indigestion. In this light Elgar’s escapism is a paradoxical impulse. Like Mr. Polly’s, it is deeply embittered, but it coexists with an outward tendency not only to accept but even to strengthen the original entrapment. The next section suggests a model for this uncomfortable condition, finding it—literally—just down Elgar’s street.

Worcester Forgotten and Remembered

How often in years gone by, while pacing the lonely cloisters of our venerable cathedral, have I endeavored in imagination to refill the void with its former occupants—to note their appearance, dress, and employment—to enquire of these shadowy unrealities their history, thoughts, hopes, and aspirations, and to restore for a few moments the gorgeous pomp and circumstance of a wondrous institution now gone for ever.

—John Noake, The Monastery and Cathedral of Worcester (1866)

Toward the end of his life, Hubert Leicester, Elgar’s childhood companion, fellow Catholic, Worcester stalwart, and five times mayor of the city, penned a series of contributions to its history: Notes on Catholic Worcester (1928), Forgotten Worcester (1930), How the Faith Was Preserved in Worcestershire (1932), and Worcester Remembered (1935).11 Although Elgar’s foreword to Forgotten Worcester implies that the pair were chalk and cheese in terms of personality, their social origins were similar (class, religion, upbringing on High Street), both enjoyed upward career trajectories (Leicester became a successful accountant), and both held their hometown in high esteem and relished its traditions of civic ceremony. Leicester’s books echo some of Elgar’s basic beliefs and attitudes and flesh them out in a way that Elgar himself never did. Leicester emerges from them as an ambivalent figure, filled with civic pride but deeply dissatisfied with the present and yearning for the return of a distant past that was swept away long ago in what he regards as a violent catastrophe.

Leicester’s introduction to Forgotten Worcester strikes a note of solemn local patriotism. He has written the book solely to satisfy a request from the mayor. He hopes that the work will confirm the importance of the city and inspire the native.12 He then lays out a personal interpretation of “History” in the large—not just the history of Worcester, but that of England as a whole over two millennia. The first era (1–669 C.E.) was pagan, and he passes over it swiftly. For Worcester, the second (669–1155) started at the time of the conversion of the kingdom of Mercia to Christianity. Society was now shaped by the teachings of the Church, which upheld a duty to administer to the needs of the less fortunate. To this end abbeys, friaries, priories, convents, churches, and cathedrals were established, which provided relief to the poor, sick, and orphaned, and education to those who needed it. This regime maintained direct links between the community, the spiritual values of its people, and the dispensation of local charity. “Rates [local taxes], as we know them to-day, were things unheard of.”13 The third era (1155–1540) witnessed the development of trade and commerce and the awakening of “the general desire to acquire money”; it thus contained the first seeds of modern decline. The activities of the Church were now ably supplemented by guilds and corporations, which regulated the behavior of tradesmen, arranged public entertainments, and provided insurance for the citizens against misfortune, criminal damage, or loss. The era ended with society’s definitive fall from grace: “This dual management, for satisfying the new wants of the community, continued till the sixteenth century, when the religious houses were dissolved, the guilds banned, and the lands and possessions of both bodies (which were really the property of the people) seized by the Crown.”14 Leicester’s characterization of the fourth era (1540–1930) is terse and devastating: “After the religious houses were abolished, the financial, or mercenary age commenced, and brought with it the extension of the rent system, the introduction of rates, taxes, and ground rents, and the reduction of most of our institutions to a mercantile basis. And in this state we are today.”15

Leicester’s books periodically return to aspects of this narrative and expand upon the details. Mention of the English Reformation is usually scornful, with the word placed within quotation marks: “the fateful ‘Reformation’”; “what is known as the ‘Reformation.’”16 Leicester regards its immediate outcomes as sacrilege and rapine, and its long-term impact as far-reaching social alienation. Worcester Remembered tenderly records a catalogue of “outrages” committed against the religion of the city: the prohibition of the Mass, the abolition of altars and crucifixes, the despoiling of “sacred images,” the reuse of consecrated altar stones as paving, and the plunder of the shrines of Saint Oswald and Saint Wulstan. Heavy fines imposed by the Crown on recusants enriched the exchequer and coerced the English people into accepting Protestantism against their true wishes.17 Leicester takes similar pains in documenting the damage inflicted on Worcester Cathedral by Cromwell’s troops during the English Civil War: the destruction of “sacred statues,” the smashing of stained glass, the use of the building as a stable, and “other atrocities too vile to be mentioned.”18 The long-term consequences of the Reformation were no less dire. The chapter in Forgotten Worcester on “Ancient Guilds as They Affected Worcester” praises the pre-Reformation guild system for its reliance on local beneficence, pride, and solidarity, and aims several barbs at the modern system of state welfare provision. “All these services were performed by the Guilds in days when men were prepared to pay for what they received, and did not expect, as so many do to-day, to receive these benefits as their right… . In the trade Societies of to-day, the main objects are to force up wages and obtain for the worker constant increase of pay, while those of the masters have it as their object to so manage matters that the price of commodities may be put up to the advantage of the producer.” Similarly, in modern times insurance is provided by “commercial companies run for the sake of profit.” These developments owe their existence ultimately to the expansion of the state in the sixteenth century, when poor laws and workhouses had to be established to substitute for the work of the monasteries and guilds, and taxes levied to pay for them.19

Leicester’s views appear to rest on a combination of staunch local patriotism and middle-class resentment of taxation and state bureaucracy. Welfare is best administered between and among fellow citizens; when the state steps between those who fund and receive welfare, both suffer. His tone of disillusion in this regard may owe something to the industrial strife of the 1920s and the economic depression of the 1930s. What is distinctive about his writings, however, is the combination of these politically Conservative themes with a strong emotional attachment to a lost culture of Catholicism, which casts an air of mystery and romance over the whole account. He rejects the prevailing view of the English Reformation as a heroic phase of national self-definition. His condemnation of central government’s “crimes” against the English people is reminiscent of early-nineteenth-Century radical texts such as William Cobbett’s History of the Protestant Reformation (1824–27) and Rural Rides (1830). His devotion to medieval Catholicism and its social mission echoes the opinions of the Victorian architect and medievalist A. W. N. Pugin, whose writings compared the society of the Middle Ages favorably with that of the present. (Pugin regarded the modern city as filthy, cramped, violently policed, and brutal in its effect on the poor.)20 These themes became commonplaces of Victorian medievalism, articulated by Thomas Carlyle and the “Young England” circle, and then by John Ruskin and the Christian Socialists. Later they were taken up by William Morris and the Guild Socialist movement.21 Leicester thus writes within a tradition that challenges the basic narrative about English identity and history made by British governments and the Church of England for several centuries.

The connections between Leicester and Elgar are oblique yet intriguing, given the men’s common origins. In 1905, during Leicester’s first stint as mayor of Worcester, he arranged for Elgar to be awarded the freedom of the city. At the ceremony Elgar (wearing his Yale University robes) processed solemnly through the streets alongside the civic dignitaries.22 In 1930, possibly influenced directly by Leicester’s writings, Elgar composed his Severn Suite, whose movements evoke Worcester’s medieval past (“Worcester Castle,” “Tournament,” “Cathedral,” “Commandery”).

Elgar’s letters contain an abundance of references to the distant past of his own life, many of them associated with his childhood and early adulthood in Worcester, and, especially in later years, infused with passionate regret and longing for a lost idyll.23 Leicester’s books, too, have their warm domestic aspects: they blend personal and family memories, legend and hearsay, and genuine historical findings, merging personal and collective memory. To be sure, aside from the decision to set Cardinal Newman’s “The Dream of Gerontius”—at the time a controversial move—Elgar seldom advertised his attachment to the mystery and majesty of Catholic worship, and he certainly did not utter public polemics on the subject: he was a cultural Catholic rather than a militant believer.24 Still, in 1931 he could write about the College Hall in Worcester: “The College Hall is a favorite subject for meditation with me, carrying, as it does, the happiest memories of great music, with a halo of the middle ages combined with an odour of sanctity which even the sacrilege of the reformers has not wholly destroyed.”25 (This sensual description resonates with Elgar’s more general attachment to display and ceremonial, his liking for “colorful” music, and his impatience with the English taste for the plain.)

But Leicester’s most significant parallels with Elgar are found at the levels of tone and rhetoric. Leicester’s books are marked by an undercurrent of loss and anger and a sense of belatedness. The distant past is characterized by perfect unity; this was the time of “what had always been the ‘one faith’ of Christendom.”26 Past and present worlds are separated by a definitive break at 1540, a break violently imposed by external forces against which the inhabitants of England, and Worcester in particular, are helpless. Although Leicester looks forward to the future unification of the Anglican and Catholic churches, his remarks in that regard sound as much like pious formulae as real hopes. When he lets down the guard of the respectable citizen and diligent antiquarian, Leicester emerges, like Elgar, as a man of contradictions: an accountant who hates commercialism and a Catholic with a sense of disinheritance within the city to which he professes devotion. As with Elgar, there is in practice no easy way out of this predicament. For the present, a better world can be glimpsed only through memory and imagination.

Some Musical Escape Routes

Rather than presenting a comforting illusion, Elgar’s best music occasionally stumbles across the intuition of a happy existence that for the most part remains out of reach. It is escapist in this sense, and numerous passages and techniques could be cited in illustration. The pastoral interludes in the choral and symphonic works (Caractacus, In the South, Falstaff, the symphonies) could be viewed as isomorphic to Mr. Polly’s weekend excursions: they are wonderfully idyllic, but they do not last. Thematic reminiscence in Elgar’s works—the recollection of material from an earlier movement in a later movement—is often as sensual as his memory of College Hall in Worcester: the recollections are prepared portentously, presented mysteriously, and cloaked in a hazy atmosphere. The cadenza of the Violin Concerto and the slow movement of the Second Symphony contain wellknown examples. (By contrast, the musical “present” of the later movement is usually far more prosaic.) There is a common process in Elgar’s symphonic works whereby a grandiose climax swiftly recedes and gives way to intimate, introspective music—a process known in the literature as “withdrawal.”27 During the 1910s, Elgar developed a tendency to conclude his major compositions with bitter irony or with palpable, unresolved duality. His last two substantial symphonic works, Falstaff (1913) and the Cello Concerto (1919), along with The Music Makers (1912), endure painful ruptures in their final bars, which push dream and reality, memory and present consciousness into stark oppositions. In all these examples, escape is characterized by displacement: digression from the main “argument” or “frame” of a piece. Such displacement is almost always corrected in the end. Interludes recede, reminiscences fade, and movements end with the reiteration of their “proper” frame and close in the “home” key. It is very unusual for a movement in one of Elgar’s scores to be permanently disrupted by an escapist digression and its overall course altered. Just as in Elgar’s life, there is no equivalent to Mr. Polly’s successful act of resistance. Despite their shared determination to succeed in a caste-bound society, Elgar possessed little of Wells’s resilience or enterprise, traits the author drew upon and transmuted to create the character of Mr. Polly. This is not to say the displacements leave no mark on Elgar’s music. Reality prevails, but at a price: it is diminished and discredited. In the final bars of Elgar’s later symphonic works, closure is achieved, but resolution is absent.

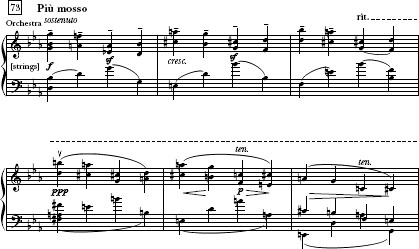

A related form of escape by displacement is illustrated by Elgar’s characteristic use of abrupt tonal shifts or slippages. In many cases these shifts are soon reversed, allowing the music to resume in its original tonal sphere. They are parenthetical utterances, indicating moments of distraction or fleeting reverie. A late but charming example is found in a piece titled “Dreaming,” from the 1931 Nursery Suite (Example 1). Drowsiness turns briefly to deeper slumber six bars after rehearsal number 57, as a 6–4–2 chord on D enters, the parts marked lento, espressivo, pianissimo, and the double basses entering briefly to darken the color. But the music soon finds its way back to the tonic E

enters, the parts marked lento, espressivo, pianissimo, and the double basses entering briefly to darken the color. But the music soon finds its way back to the tonic E and continues on its way. The examples could be multiplied. For instance, the songs from Elgar’s incidental music to the stage play The Starlight Express—given to a character known as the Organ Grinder—contain three such digressions—again flatward—each of which coincides with a call for a return to the dreams and enchantment of childhood. The reassertion of the mundane adult world is effected briskly, and sometimes brutally. The opposition between dream and reality is starkly underlined.28

and continues on its way. The examples could be multiplied. For instance, the songs from Elgar’s incidental music to the stage play The Starlight Express—given to a character known as the Organ Grinder—contain three such digressions—again flatward—each of which coincides with a call for a return to the dreams and enchantment of childhood. The reassertion of the mundane adult world is effected briskly, and sometimes brutally. The opposition between dream and reality is starkly underlined.28

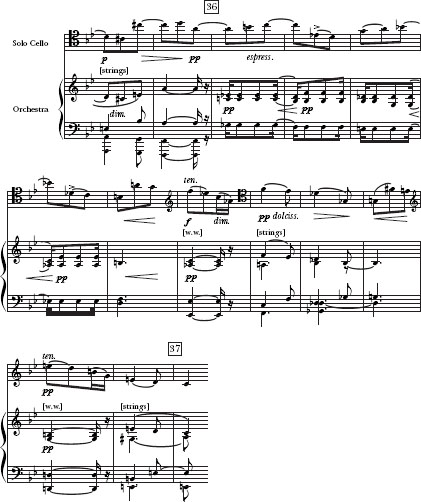

In the symphonic works, tonal displacement occasionally receives more complex treatment. Although in the final analysis an uncomfortable duality is upheld, the effect of the displacement is felt longer. In Example 2, for instance, from the Adagio of the First Symphony, a movement cast in D major, a sequence in A major underpins a rising diatonic linear pattern in the upper voice, beginning C#–D–E–F# (Examples 2a and 2b). The sequence stops when the progression turns to G# instead of G#. This turns out to be a chromatic passing note that merely delays the appearance of dominant harmony (with G#s) and then tonic harmony, completing an implicit progression of a sixth in the upper voice: C#–A. The sequence then begins again. But in the meantime the G is expanded by means of a G major chord and its applied dominant. During that expansion, the regular progress of the sequence is halted; the pulse is less marked; the texture broadens; musical time slows. This example does not present an absolute duality: the music of the sequence already possesses an idyllic tone, and the G major harmony is well integrated into the musical paragraph by virtue of the underlying voice-leading. Indeed, the broadening of the textual and rhythmic dimensions impels the music onward and allows, as it were, the sequence to unfold all the more expansively on its repetition. In this view the G major music stores up a kind of potential energy, which is released on the return to A major, the overall key of this passage.

Example 1. “Dreaming,” Nursery Suite, rehearsal nos. 57–58

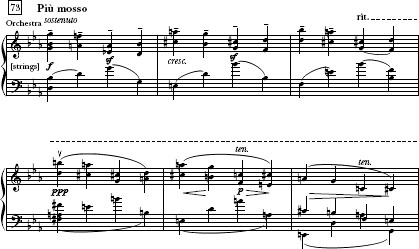

In Example 3, from the Larghetto of the Second Symphony, the mustering of forces for a grand climax is interrupted and partially reversed by a shift from a B-flat major/G minor sphere to D major, combined with a slowing of tempo, a sudden reduction in dynamics, and a fleck of color from the clarinets. Here the sense of purpose and drive of the preceding bars is sapped—not altogether, but the gradual buildup taking place during this section has to begin all over again in the new key, D major. The music finds its way back to the tonal center of this section of the movement—F major—although much more gradually than in the excerpt from the Adagio from the First Symphony cited in Example 2a. Still, F major is asserted unambiguously at the climax of the Larghetto (see full score, rehearsal number 76) and is stabilized thereafter, so the section overall is tonally closed.

Example 2a. Adagio, Symphony no. 1 in A-flat Major, op. 55.

Example 2b. Adagio, Symphony no. 1 in A-flat Major, op. 55, voice-leading reduction.

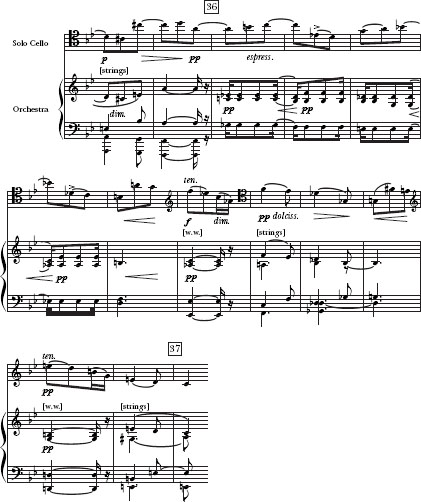

The Adagio of the Cello Concerto is perhaps the closest Elgar ever comes, from the perspective of tonality, to a wholly “escapist” movement. The piece is framed by an eight-bar period in B-flat at its beginning and end, but otherwise the tonality is fluid. A few ideas are repeated in irregular sequences, moving swiftly through distant modulations with no apparent rationale for the choice of keys that are briefly established. In Example 4, where the harmonic progressions are based around chromatic motions in parallel sixths, the abrupt tonal shifts are coordinated with changes of instrumental color (woodwind replacing strings) and, for the soloist, upward leaps to 9–8 appoggiaturas. The movement as a whole amounts to a reverie, which acquires a kind of coherence only through the consistency of its waywardness. Its melancholy quality arises not just from its obsessive dwelling on a handful of ideas but from its determination to be always distracted by them.29 Still, this attitude is sustained for only sixty bars; the opening of the finale reasserts conventional rhetoric and function and gets the concerto back on course.

Example 3. Larghetto, Symphony no. 2 in E-flat Major, op. 63.

The techniques illustrated by these examples have long been admired by commentators on Elgar. They are usually understood—surely correctly—as evidence of some kind of musical-cum-psychological dualism. According to Diana McVeagh:

The half-shy, half-impulsive moments in Elgar’s music often come from a chord escaping from the prevailing tonality either to double back at once … or to turn right aside … [here she cites part of Example 3]. This was from the first a personal fingerprint … Always the unexplained chord is itself simple; its aloofness comes from its alien context, it is lingered over in a sudden hush, and its effect is of a withdrawal, a shrinking for an instant into a secret self, that is the essence of Elgar the dreamer.30

Example 4. Adagio, Cello Concerto in E Minor, op. 85.

And Wilfred Mellers puts it thus:

In music such as this [part of Example 4] the rhetorician is silenced; in the free rubato of the lyricism an intimate human voice speaks directly to you and me, while an unexpected chord or modulation reveals the private heart beneath the public manner.31

The idea of a “secret self” or “private heart” into which Elgar “withdraws” is a commonplace of the critical literature. Although occasionally pushed to injudicious extremes, it is undoubtedly invited both by his behavior and by his music.32

But one might venture a further, less familiar observation, for there is a striking feature common to all these examples of tonal displacement. In each case the moment of “withdrawal” or “shrinking” coincides with an alteration in what might be termed the musical dynamic (referring now to an analogy with forces in mechanics, not loudness). On the one hand, there is a certain relaxation; on the other, suspense, like a holding of the breath. The relaxation is partly rhythmic—the effect of slowing, pausing, or the nonarticulation of pulse—and partly the result of the harmonic shift. Since the new chord has no conventional function in the old key, the harmonic logic that might otherwise link the music’s past and present and point on to its future is suspended. For a moment, as it were, things seem easy: a weight is lifted; the pressure of directed motion is released. In Examples 2 and 4, the upward leaps at the moments of tonal shift, followed by unhurried descents, accelerating only gradually, present unmistakable images of floating. These metaphors of weight and motion clarify the character of the escape under discussion here: it is an escape of the body. The music articulates the first half of Mr. Polly’s conviction: somewhere, however inaccessible, exist “pure and easy and joyous states of body and mind.”

The notion of bodily escape in Elgar is striking because so many aspects of his mature style—style in both the sense of his personal behavior and the idiom of his music—can be linked to the Victorian disciplining of the male body. Elgar did not attend one of the great public schools, such as Eton or Rugby, but something of the ethos of those institutions—the value of strenuous physical exercise and its relation to virtue and chivalry (“fair play”) and to British imperialism—nevertheless seeped into his consciousness and into his music, too. His liking for a regular, clearly marked pulse, usually in march time; his use of florid, “courtly” gestures in his melodic lines; the many broad, serene tunes that sit precisely in the register of a male tenor voice—whether or not they are sung—could all be cited. By the same token, the emphasis on chivalry and medieval romance in Elgar’s choice of texts, his attraction to grand ceremonial, his call for English music to adopt “an out-of-door sort of spirit,” and his description of the motto theme of the First Symphony as a “sort of ideal call” resonate strongly in their various ways with the constructions of masculinity by Thomas Carlyle, Charles Kingsley, and others.33 In many cases those constructions centered on the regulation and control of masculine “energy.” On these terms, Elgar’s sudden tonal shifts represent the rare moments when the regulating practices break down and the energy is released in some new form. The results are not, as the Victorians might have feared, chaotic, but marvelously easeful.

Part of Elgar believed in the self-disciplines and even embraced them; he probably never wholly lost his tendency to high-minded Victorian idealism, however diluted or overwritten by other attitudes it may have become in later years.34 It is of crucial importance, however, to recognize that Elgar himself did not live up to the ideals of physical masculinity sketched out here. Indeed, his mental indigestion appears to have manifested itself rather clearly in the movements of his body. Contemporary accounts described Elgar as nervous, twitchy, and ill at ease in formal company; caricatures of him conducting portrayed him as hunched, bony, and jerky. If anything, Elgar’s body fitted more closely the category of the neurasthenic in the late Victorian discourse on “decadence” and social “degeneration.”35 In this light, Elgar’s carefully posed photographs and his bristling moustache—and indeed the supposed “self-portrait” of the final Enigma variation—must be understood as compensatory strategies. The famous photograph taken by William Eller in August 1900 as Elgar was finishing Gerontius shows us, as David Cannadine puts it, “Elgar as he wanted to be seen, yet giving away more than he knew: the tradesman’s son trying too hard to conceal the fact that he was.”36 Accordingly, many of Elgar’s sudden tonal shifts—along with some of his interludes, recollections, and “withdrawals”—could be said to acquire a ring of truth. This is not a truth along the lines of “here is the true Elgar—the poet, the dreamer, not the Edwardian gentleman,” for the assiduously cultivated image of the Edwardian gentleman was also the true Elgar. Rather, it is the displacement that matters, and the overall pattern of psychological fault lines that result.

In conclusion, it seems appropriate to distinguish two phases of Elgarian escape. In the first, Elgar attempts to escape his predicament through selfimprovement, but in so doing entraps himself further. Evidence for this compulsion can be discerned in his behavior, appearance, and music. But its effects reach even beyond Elgar’s own lifetime. For decades after his death, Elgar’s image was tarnished by his associations with nationalism, conservatism (artistic and political), and imperialism. These factors have helped confine him to the fringes of music history textbooks and of concert programs (at least, outside the United Kingdom), and until recently made academics wary of him as an object of study.37 Despite books like this one, Elgar may never wholly escape that marginalization. But the self-defeating first phase of escape is a precondition for the second, emphatically musical phase. At this point the opportunity arises for Elgar to develop some of the most affecting and powerful qualities of his music and to create a good deal of what we now value highly in his work. It was, in a way, part of Elgar’s genius to entrap himself so tightly; perhaps only a shopkeeper’s son could have brought it off with such conviction.

NOTES

1. On the topic of Elgar and childhood, see Michael Allis, “Elgar and the Art of Retrospective Narrative,” Journal of Musicological Research 19 (2000): 289–328; and Matthew Riley, “Childhood,” in Edward Elgar and the Nostalgic Imagination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), chap. 5.

2. Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius and The Apostles carry epigraphs from Ruskin and Morris, respectively. Elgar quoted Kingsley in his lecture “English Composers” as professor of music at the University of Birmingham, and may have tacitly invoked him during an interview with Gerald Cumberland in 1905. Elgar probably identified with the idealistic aims of these writers, although the extent to which he endorsed their specific political agendas is unclear. See Brian Trowell, “Elgar’s Use of Literature,” in Edward Elgar: Music and Literature, ed. Raymond Monk (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1993), 197, 228–39; Edward Elgar, A Future for English Music and Other Lectures, ed. Percy M. Young (London: Dennis Dobson), 91.

3. J. R. R. Tolkien, Tree and Leaf: Including the Poem “Mythopoeia” (London: HarperCollins, 2001), 61. Tolkien’s observation that critics have made the confusion “not always by sincere error” may even hint at the connections between modernist aesthetics and authoritarian politics in the 1930s.

4. H. G. Wells, The History of Mr. Polly (London: Penguin, 2005), 14.

5. See Trowell, “Elgar’s Use of Literature,” 182–326.

6. Wells, Mr. Polly, 206.

7. Rosa Burley and Frank C. Carruthers, Edward Elgar: The Record of a Friendship (London: Barrie and Jenkins, 1972), 38.

8. As witnessed by his letters to the Times Literary Supplement between 1919 and 1923, discussed (disparagingly) by Trowell, “Elgar’s Use of Literature,” 201–3.

9. Wells, Mr. Polly, 159.

10. A possible exception to this rule is the explosion that took place after one of Elgar’s chemical experiments in his garden shed in Hereford. But this was apparently accidental. W. H. Reed, Elgar as I Knew Him (London: Victor Gollancz, 1936), 39.

11. Hubert A. Leicester, Notes on Catholic Worcester (Worcester: Ebenezer Bayliss, 1928); Forgotten Worcester (Worcester: Trinity Press, 1930); How the Faith Was Preserved in Worcestershire (Worcester: Ebenezer Bayliss, 1932); Worcester Remembered (Worcester: Ebenezer Bayliss, 1935; repr. East Ardsley: S. R. Publishers Ltd., 1970). See also Leicester’s Notes on the History of Freemen (Worcester; printed for private circulation, 1925).

12. Leicester, Forgotten Worcester, 15, 19.

13. Ibid., 17.

14. Ibid., 18.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid., 64; Leicester, Worcester Remembered, 49.

17. Leicester, Worcester Remembered, 50–52.

18. Leicester, Forgotten Worcester, 65; Notes on Catholic Worcester, 16.

19. Leicester, Forgotten Worcester, 92, 104, 113, 112.

20. Leicester would have approved of Pugin’s drawing of “contrasted residences for the poor” from Contrasts (1836). As the historian of religion Nigel Yates has observed, “The noble monastic buildings are replaced by a utilitarian workhouse; a diet of beef, mutton, bread and ale by one of bread and gruel; the poor person in his quasimonastic habit by a beggar in rags; the master dispensing charity by a master wielding whips and chains; decent Christian burial by the dispatch of the corpse for dissection by medical student; and the discipline of an edifying sermon by that of a public flogging.” A. W. N. Pugin, Contrasts and The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture (Reading: Spire Books Ltd., 2003), app., fig. 14; Nigel Yates, “Pugin and the Medieval Dream,” in Victorian Values: Personalities and Perspectives in Nineteenth-Century Society, ed. Gordon Marsden (London and New York: Longman, 1990), 60–70, esp. 65.

21. See William Stafford, “‘This Once Happy Country’: Nostalgia for Pre-Modern Society,” in The Imagined Past: History and Nostalgia, ed. Christopher Shaw and Malcolm Chase (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1989), 33–46; and Frances Hutchinson, The Political Economy of Social Credit and Guild Socialism (London: Routledge, 1997), 14–15.

22. See Jerrold Northrop Moore, Edward Elgar: A Creative Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), 465.

23. Allis speaks of a “surfeit of references to past events” in “Retrospective Narrative,” 291; see also 328 for some examples.

24. See Charles McGuire’s essay in this volume for a detailed discussion of Elgar’s Catholicism.

25. 3 June 1931 in Jerrold Northrop Moore, ed., Edward Elgar: Letters of a Lifetime (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), 438. Cited also in Allis, “Retrospective Narrative,” 322.

26. Leicester, Notes on Catholic Worcester, 16.

27. For a discussion of the history of this idea, see Riley, “Identity,” chap. 6 in Nostalgic Imagination.

28. Two of Elgar’s letters refer to his liking for flatward modulation: to A. J. Jaeger, 19 September 1908, and to Ernest Newman, 27 October 1908. See Jerrold Northrop Moore, ed., Elgar and his Publishers: Letters of a Creative Life (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 2:710; and Moore, Letters of a Lifetime, 199. For a discussion of the modulations in the Organ Grinder’s songs, see Riley, Nostalgic Imagination, chap. 5. Numerous antecedents for Elgar’s flatward shifts can be found in nineteenth-Century music, most notably in Schubert. For a discussion that links these phenomena with modern philosophical dualism, see Karol Berger, “Beethoven and the Aesthetic State,” Beethoven Forum 7, ed. Mark Evan Bonds (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), 17–44.

29. For further discussion of melancholy in the Cello Concerto, see Christopher Mark, “The Later Orchestral Music,” in The Cambridge Companion to Elgar, ed. Daniel M. Grimley and Julian Rushton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 166–69.

30. Diana McVeagh, Edward Elgar: His Life and Music (London: J. M. Dent, 1955), 200–201.

31. Alec Harman, Anthony Milner, and Wilfred Mellers, Man and his Music (London: Barrie & Rockliffe, 1962), 970.

32. See Riley, Nostalgic Imagination, chap. 6.

33. Elgar, A Future for English Music, 57; letter to Ernest Newman, 4 November1908, cited in Moore, Letters of a Lifetime, 200.

34. Elgar’s biographer Basil Maine referred to “the growing scepticism of Elgar’s attitude to life,” but added that “it is one of the many contradictions that are to be discerned in his character, that this scepticism exists in him together with an intense and noble idealism. The problem is to discover which of the two is the more deeply rooted.” Basil Maine, Elgar, His Life and Works (London: G. Bell & Sons, 1933), 1:197.

35. See for instance, the caricature of Elgar conducting (1905), reproduced without attribution in Elgar, A Future for English Music, 44–45; and the two Edmond Kapp drawings of Elgar conducting held by the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham. See also the extract from Gerald Cumberland’s Set Down in Malice: A Book of Reminiscences (London: Grant Richards, 1919), reproduced in An Elgar Companion, ed., Christopher Redwood (Ashbourne: Sequoia/Moorland, 1982), 130–36; and the commentary on this passage by Byron Adams, “The ‘Dark Saying’ of the Enigma: Homoeroticism and the Elgarian Paradox,” in Queer Episodes in Music and Modern Identity, ed. Sophie Fuller and Lloyd Whitsell (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002), 223–24.

36. David Cannadine, “Sir Edward Elgar,” in The Pleasure of the Past (London: Collins, 1989), 121.

37. This tradition is maintained in Richard Taruskin’s The Oxford History of Western Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), which ignores Elgar entirely.

enters, the parts marked lento, espressivo, pianissimo, and the double basses entering briefly to darken the color. But the music soon finds its way back to the tonic E

enters, the parts marked lento, espressivo, pianissimo, and the double basses entering briefly to darken the color. But the music soon finds its way back to the tonic E and continues on its way. The examples could be multiplied. For instance, the songs from Elgar’s incidental music to the stage play The Starlight Express—given to a character known as the Organ Grinder—contain three such digressions—again flatward—each of which coincides with a call for a return to the dreams and enchantment of childhood. The reassertion of the mundane adult world is effected briskly, and sometimes brutally. The opposition between dream and reality is starkly underlined.28

and continues on its way. The examples could be multiplied. For instance, the songs from Elgar’s incidental music to the stage play The Starlight Express—given to a character known as the Organ Grinder—contain three such digressions—again flatward—each of which coincides with a call for a return to the dreams and enchantment of childhood. The reassertion of the mundane adult world is effected briskly, and sometimes brutally. The opposition between dream and reality is starkly underlined.28