Elgar and the Persistence of Memory

BYRON ADAMS

The attribute of intelligence is not to contemplate but transform.

—Jean Piaget, Psychology and Epistemology, 1972

“I am self-taught in the matter of harmony, counterpoint, form, and, in short in the whole of the ‘mystery’ of music,” declared Edward Elgar in a 1904 interview published in The Strand Magazine. The composer then laid the necessity for self-tutelage at the feet of his humble birth: “When I resolved to become a composer and found that the exigencies of life would prevent me from getting any tuition, the only thing to do was to teach myself… . I read everything, played everything, and heard everything I possibly could.”1 Elgar’s claim is characteristically flamboyant and self-dramatizing, but it is essentially accurate. All of Elgar’s biographers have traced the stages of Elgar’s learning, demonstrating that the composer was indeed essentially self-taught in music theory and that he amassed his formidable technique largely through his own initiative.2

As the interview suggests, Elgar was clear concerning his unconventional education, the facts of which were well-known within his profession as well as in academia. When the composer was awarded an honorary doctorate from Cambridge in 1900, the Public Orator pointedly lauded Elgar as an “autodidactus.”3 But if, like Schoenberg, Elgar was one of the stunningly successful autodidacts of music history, the question arises how his self-education shaped his later habits and choices. What exactly does it mean to be an autodidact, that is, one who undertakes to educate oneself?

Applied to Edward Elgar, this question proves to be of great import, especially as several possible answers can illuminate aspects of both the man and his music. Recent investigations of autodidacts in the fields of social history and educational psychology provide a lens through which to view the experience of this ardent autodidact from Worcester. A clearer outline of Elgar’s personality and creative process emerges when he is placed among contemporary British working-class people striving to better themselves. New work in educational psychology may help reveal the effect that his early learning experiences may have had on several mature compositions. Definitive conclusions cannot be reached in an essay of this size: with a subject as complex as learning—especially when applied to Elgar’s multifaceted and contradictory personality—it will only be possible to provide a starting point for a much longer scholarly journey.

The Voracious Reader

Print is the technology of individualism.

—Marshall McLuhan, Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man, 1962

To comprehend better Elgar’s keen need for self-education, the true nature of his class background must first be described without sentimentality. Although many writers on Elgar speak of his family as lower-middle-class tradesmen, this designation became appropriate only several years after Elgar’s birth in 1857. Elgar was born into a working-class family that later rose in the world to a marginally higher station. During the course of a conversation recorded by Siegfried Sassoon, Elgar’s patron Frank Schuster summed up the social status of the composer’s parents: “E[lgar]’s mother [was a] barmaid at a little pub. E[lgar]’s father used to ride around the country on a cob and tune pianos for the local gentry.”4 (Elgar himself gave a similar description of his father, with the telling addition that “he never did a stroke of work in his life.”)5 Born in 1822, William Elgar came to Worcestershire from Dover with some practical musical skills, the ability to tune a piano, and a very modest education; at least one of his son’s biographers has called William “semi-literate.”6 Despite his thoroughbred mare and cultivated air of gentility, William Elgar’s modest financial status, lack of education, and manner of labor left him poised between the lowest rungs of the lower-middle class and the upper echelons of the unvarnished working class. When William took his son along on his professional visits to Madresfield Court, palatial home of the noble Lygon family, young Edward was dispatched to play with his social equals, the children of the head gardener.7

If the class status of his father was ambiguous, the origins of Elgar’s mother, Ann (née Greening), were frankly working class.8 Born in the same year as her husband, Ann came from a family of poor and largely illiterate farm laborers; for a very few years she attended the local parish school at Weston-under-Penyard.9 Ann learned to read during her abbreviated formal education and evinced an early love of learning. As a teenager, she left her native Herefordshire to settle in Worcester, working at a tavern called The Shades.10 Here she met her future husband, with whom, after their marriage in 1848, she had seven (or possibly eight) children.11 At first the couple lived simply, as befitted their modest social status and income. Shortly after settling in Worcestershire, William Elgar became a fixture on the local musical scene, playing among the second violins in various ensembles and, unusual for an Anglican, accepting the post of organist of St. George’s Roman Catholic Church in 1846.12 These musical odd jobs provided a welcome supplement to his income as an itinerant piano tuner. In 1860 William Elgar, who was luckily assisted by his hardworking brother Henry, opened a music shop at 10 High Street in Worcester. Due to Henry Elgar’s diligence, and in spite of William’s indolence, the shop was moderately prosperous.13 With the opening of this shop, young Edward’s family made its modest ascent into the ranks of lower-middle-class tradesmen.

The more censorious among their small-town neighbors may well have considered the Elgar family to be less than perfectly respectable. William used his pay to imbibe more than a pint or two, an expensive habit that was the source of continuing friction at home. Worse yet, in 1852 Ann Elgar converted to Roman Catholicism, the result of having followed her husband to St. George’s when he played organ for Sunday mass. Ann’s conversion, made in the face of her husband’s exasperated disapproval, was audacious indeed for the daughter of Protestant farm laborers in a rural town.14 Not only was she seeking religious consolation but self-assertion in rigid little Worcester.

Ann Elgar’s desire for individual choice, joined with a lifelong habit of reading, puts her squarely within the tradition of the autodidacts whose testimonies are collected in Jonathan Rose’s The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes.15 Beginning in the late eighteenth century and concluding in the latter decades of the twentieth century, Rose’s book, though filled with statistics regarding the education, reading, and cultural preferences of its subjects, is most valuable for its testimonies. In a manner as admirable as it is unusual, working-class voices rise from Rose’s pages, their words often eloquent. Rose’s procedure of interlacing testimony with fact and sociological analysis produces a landscape teeming with earnest self-educators, which challenges received opinion on the nature of the working class during the Victorian, Edwardian, and Georgian eras.

If placed in the company of the working-class learners who populate Rose’s history, Ann Elgar is unusual only in that, given the rigid gender boundaries of the time, fewer women are found in their ranks than men.16 Given the obstacles, she must have been extraordinarily determined to gain control over her own lot and improve the lives of her children. The seed of Ann’s ambitions bore fruit with two of her five surviving children: Ellen Agnes, who took the vows of a nun after her mother’s death and eventually was appointed prioress of the Convent of St. Rose of Lima at Stoke; and her oldest surviving son, Edward, who became successful beyond his mother’s wildest hopes.17

Nowhere is Ann Elgar’s strength of character demonstrated more plainly than in her struggle to obtain the best education possible for Edward. He was born thirteen years before the 1870 Education Act (also known as the Forster Act), which, as Rose notes, “supplemented the church schools (which had never served the entire population) with state schools governed by elected school boards.”18 Before this reform, working-class children generally received a scant few years of instruction. Before 1870, practically no educational opportunities were open to the working classes; those that existed were private and often affiliated with religious organizations. For working-class Roman Catholics, the situation was often dire.

Elgar was first sent to a Dame school, a charity establishment primarily intended for girls. This school was run by Miss Caroline Walsh, whom Charles Edward McGuire accurately characterizes as a fervent “Catholic convert.”19 On the basis of the available evidence, Miss Walsh’s Dame school—a designation that does not refer to the gender of the instructors but, as Rose writes, is “a generic term applied to any working-class private school”—seems to have been at least competently organized, serious, and decorous.20

The quality of Elgar’s next school, St. Anne’s, is open to question based on the composer’s own memories. This school was established by the venerable and Catholic Berkeley family at their estate, Spetchley Park, as a charitable institution intended chiefly for those children whose parents worked on the estate itself.21 In a letter of 1912 to Ernest Newman, who was visiting Spetchley Park at the time, the composer reminisced that “S[petchley] is the village where I spent so much of my early childhood—at the Catholic School house: my spirit haunts it still.”22 Perhaps the general context of this letter to Newman, which mostly concerned Elgar’s The Music Makers, a deeply autobiographical score, prompted Elgar to exaggerate Spetchley’s significance, as he spent just two terms there.23 The more so that this recollection was confided to none other than Ernest Newman, who related in 1955, quite late in his own life: “Elgar told me that as a boy he used to gaze from the school windows in rapt wonder at the great trees in the park swaying in the wind.”24 It is disconcerting, however, that the adult composer’s chief memory of St. Anne’s was looking out the schoolroom window—rather than anything he might have learned there.

The last few years of Elgar’s formal education, from 1869 to 1872, were spent at Francis Reeve’s school, Littleton House, which was situated across the Severn River from Worcester Cathedral. Elsewhere in this volume, McGuire paints a vivid portrait of this institution, and the young Elgar was lucky indeed to attend what was, in essence, a modest Catholic “public” school run by a professional schoolmaster, for profit.25 How Ann Elgar managed to pay for Edward’s schooling there is a wonder, given the slender household budget. Reeve must have been an effective teacher, since the adult Elgar once wrote him a brief encomium that declared, “Some of your boys try to follow out your good advice & training, although I can answer for one who falls only too far short of your ideal.”26 That Elgar remained in school until fifteen is a testament to his mother’s steely determination in the face of both fluctuating income and the easygoing indifference of her husband.27

Through her love of reading, her own writing, and her taste in authors, Ann Elgar neatly fits the profile of a working-class autodidact of nineteenth-century Britain. To her granddaughter Carice, Ann wrote in 1897, “When I was a very young girl I used to think I should read all the books I ever met with.”28 (Recall Elgar’s own testimony, quoted previously, that “I read everything, played everything, and heard everything I possibly could.”) Like many others of her class, Ann knew instinctively that learning would give her a greater measure of agency over her inner life. One working-class autodidact testified: “Life only becomes conscious of itself when it is translated into word, for only in the word is reality discovered.” Of this observation, Rose notes: “That was the autodidacts’ mission statement: to be more than passive consumers of literature, to be active thinkers and writers.”29

A striking aspect of many working-class readers was a marked devotion to poetry. Furthermore, many of these working-class readers were not merely “passive consumers” of poetry, but wrote verse themselves. Ann Elgar was one such amateur poet; though lacking technical polish, her poetry is often touching in its sincerity and infinitely more readable than the technically accomplished verse, sadly marred by a simpering gentility, written by Edward’s cultivated wife, Alice.

One of Ann Elgar’s favorite poets was the American Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, an enthusiasm she passed on to Edward.30 Longfellow’s mellifluous verse struck a resonant and sustained chord in the hearts of British readers.31 That he was fêted by the great reflected this: on an 1868 visit to England the American poet was granted degrees by both Cambridge and Oxford; was received at Windsor by Queen Victoria; and was handsomely entertained by the likes of Gladstone, Dickens, Ruskin, and Tennyson.32 As Newton Arvin remarks, “The most familiar of his poems—it will by no means do to say always his best—had entered, as it might seem ineradicably, into the popular consciousness.”33 An additional inducement for working-class British readers was that along with other American authors, Longfellow was published in inexpensive editions, for, as Rose observes, the “United States failed to sign an international copyright agreement until 1891… . Thanks to this availability, the literary conservatism so common among the working classes was reversed in the case of American authors, who were enjoyed by common readers long before they acquired respectability in critical circles.”34

Longfellow’s poetry appealed to nineteenth-century readers such as Ann Elgar for several reasons: its suave, easy-to-memorize verse patterns; a surface propriety overlaying an intense and at times vaguely erotic romanticism; its vivid descriptions and lucid narrative flow; and its unashamed appeal to the emotions. Like many, Ann Elgar may have modeled her own verse after the American’s more domestic lyrics.35 Ann’s touching couplet evoking her daughter Ellen—“Slender, thoughtful tender maid,/Like a young fawn in the shade”—is reminiscent of Longfellow’s “The Children’s Hour,” with its touching description of his own daughters: “Grave Alice, and laughing Allegra, /And Edith with golden hair.”36 In addition, chivalric romances enthralled Ann Elgar; her daughter Lucy once wrote that her mother’s youth had “been peopled from noble books, and it was in their pages she had met her friends and companions—men romantically honourable and loyal, women faithful in love even unto death; both alike doing nobly with this life because they held it as a gauge of life eternal.”37

Ann’s musical son was particularly drawn to Longfellow throughout the 1890s, setting the American poet’s verse in two large choral scores, The Black Knight, op. 25 (1889–92) and Scenes from the Saga of King Olaf, op. 30 (1895). Elgar also used Longfellow’s translation of Froissart for one of his finest songs, “Rondel,” op. 16, no. 3. (1894). Like his mother, Elgar was inspired by figures such as King Olaf; the dynamic passages extracted directly from Longfellow for Scenes from the Saga of King Olaf inspired some of the composer’s most dashing music. Furthermore, Elgar modeled the third tableau of Part I of his oratorio The Apostles, op. 49 (1902–3), “In the Tower of Magdala,” on Longfellow’s portrait of Mary Magdalene as found in the epic poem The Divine Tragedy. Although the composer’s verses are drawn from holy writ, the dramatic progression of this tableau is indebted to Longfellow’s portrayal of the penitent Magdalene.38

The book by Longfellow that held the most intense fascination for both mother and son was Hyperion (1839). In 1899 Elgar sent a copy of this volume to one of his great champions, the German conductor Hans Richter, along with a letter that confided, “I send you the little book about which we conversed & from which I, as a child, received my first idea of the great German nations.”39 One wonders what, if anything, Richter made of this sentimental gift, for Longfellow’s book is an odd hybrid production that might have puzzled any native German. Cast in four volumes, Hyperion is a Wanderroman clearly modeled upon Goethe’s Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre (1796). Longfellow retails the experiences of a young American, Paul Flemming, who, as he attempts to forget the death of the “friend of his youth,” journeys through early nineteenth-century Germany.40 Flemming’s travels are drenched in German literature and culture; indeed, the American author has his protagonist “improvise” remarkably polished translations of contemporary German poets such as Salis and Uhland. This selection of verse tastefully decorates a travelogue through the Teutonic landmarks favored by American and English tourists during the nineteenth century—such as Edward and Alice Elgar, who took several holidays to Bavaria in the 1890s. Arvin shrewdly observes that Hyperion gave such travelers “an agreeable sense of moving among the Sehenswürdigkeiten of the Rhine valley, the Alps, the Tyrol—the Rhine itself, the Rhone glacier, Mont Blanc at sunrise, the Jungfrau as seen from the Furca Pass, the ancient castle at Heidelberg, or the Franciscan church at Innsbruck.”41

Longfellow cheerfully uses his characters as mouthpieces for the expression of his own earnest aesthetic beliefs. A great many serious discussions ensue between the protagonist and a variety of interlocutors, often culminating in proclamations about the meaning of “Art” and the role of “the Artist.” Flemming and his friends are given to spouting aphorisms such as “The artist shows his character in the choice of his subject” and “Nature is a revelation of God; Art is revelation of man… . It is the creative power by which the soul of man makes itself known through some external manifestation or outward sign.”42 Although the dialogue of Hyperion is so stilted as to be virtually unreadable today, it made a deep impression upon Elgar. The young Elgar may have seen himself in Longfellow’s protagonist, whom Arvin describes as “serious, intense, high-minded, a little humorless and prudish, but sensitive and imaginative.”43 Influenced early in life by the pronouncements that passed for conversation in Hyperion, the adult composer rose to such heights himself, as when he dismisses an opinion of Roger Fry: “Music is written upon the skies for you to note down… . And you compare that to a DAMNED imitation.”44

Elgar drew from Hyperion the text for his cantata The Black Knight—in particular Uhland’s uncanny “Der Schwarze Ritter,” one of the hero’s spontaneous translations that tend to pour forth at crucial junctures of the narrative. Although the surface of Longfellow’s “romance” is genteel to the point of obliquity, the subject is German Romanticism, after all, and undercurrents of eroticism pervade the book. Newton Arvin comments that when Hyperion was published it “enjoyed at first a mild success of scandal”; perhaps American readers of 1839 knew just how to interpret obliquity.45 In any case, the protagonist’s improvised translation of Uhland’s grim poem comes at the most erotically charged moment in the novel: Flemming is alone with a comely young Englishwoman, Mary Ashburton, and is in the process of courting her. This poem describes how the Black Knight, a figure of supreme potency who combines both Eros and Thanatos, unseats the king’s son in a joust and then dances with the king’s daughter, causing the “flowerets” in her hair to fade and drop to the ground. She is thus deflowered as her partner “coldly clasped her limbs around.” Both son and daughter then wither and die before their father’s eyes, poisoned by their shame as they drink “golden wine,” as the grim knight exults in the final line: “‘Roses in the spring I gather!’” After commenting that the “knight in black mail, and the waving in of the mighty shadow in the dance and the dropping of the faded flowers, are all strikingly presented,” Longfellow’s hero remarks that Uhland’s poem “tells its own story and needs no explanation.”46

Elgar’s choice of this poem, which as Aidan J. Thomson has insightfully observed is the obverse of the narrative of Wagner’s Parsifal, speaks to a darker inheritance that the young Edward may have received from his mother.47 Elgar constantly reenacted in his own life moments of tension between repression and disclosure such as those that figure in the Mary Ashburton chapters in Hyperion with some intensity. As Jerrold Northrop Moore points out, when Ann Elgar chose excerpts from Longfellow’s volume for her scrapbook, “she copied out several passages from Hyperion bearing directly on the artist and his problems… . The first was from a scene in which the young hero contemplates the ruins of a high old castle above the Rhine, and seems to hear it say: ‘Beware of dreams! Beware of illusions of fancy! Beware of the solemn deceivings of thy vast desires.’”48

In its brevity and simplicity, Ann Elgar’s couplet describing her son Edward evinces an acute psychological penetration: “Nervous, sensitive and kind, / Displays no vulgar frame of mind.” But most children are vulgar at times, and it is healthy for them to be so. Did Ann instinctively use Hyperion as an instrument for asserting her influence over her disconcertingly emotional and, even at an early age, obsessive son? Was this her very effective way of teaching him to police his own emotions, of keeping him from slipping into a “vulgar frame of mind”? If so, what, exactly, did she fear for him? That he might slip into some kind of “vulgarity” if not warned of the “solemn deceivings” of his “vast desires”?

The effect of their shared devotion to Longfellow’s Hyperion on her son’s psychological development cannot, perhaps, be gauged fully. It is certain, however, that Ann Elgar’s taste in literature exercised a deep and lasting effect on the sort of poetry that her son set to music over the course of his career. When Elgar was moved to write poetry himself, such as for “The River,” op. 60, no. 2 (1909), his verse is reminiscent of Longfellow’s in both mood and scansion, but such was the vogue: other writers, including Tennyson and A. C. Benson, provide the same patterns. Nevertheless, a great deal of the poetry set by Elgar features the smooth stress patterns and chiming rhymes favored by Longfellow and reflects his mother’s taste for such lyric effusions. Elgar was rarely tempted to set poetry outside the canon of his own early tastes; although he knew Walt Whitman’s poetry, he was, with Parry, one of the few British composers of the time to find no musical potential in this American’s expansive verse.49

In his loyalty to the literary idioms of his youth, including classic authors, Elgar demonstrated a trait common to many working-class autodidacts: a tenacious and detailed persistence of memory. Elgar held fast to early aesthetic and literary experiences and returned to them repeatedly over the course of his adult life. In this process, acquiring used books played a large part. Like many penurious readers, Elgar soon became expert in the collection of old editions purchased at bargain prices. In Robert J. Buckley’s early biography of Elgar, published in 1904, the author testifies: “The composer revealed himself as a book enthusiast, a haunter of the remoter shelves of second-hand bookshops, with a leaning to the rich and rare.”50 Intimidated by the ever-snobbish Alice Elgar, who sent him a detailed commentary on the interview before it appeared, Buckley turns Elgar’s “haunting of second-hand bookshops” into evidence of the composer’s connoisseurship—a “leaning to the rich and rare.”51 Elgar may in fact have developed this habit in his youth because new books were expensive. Such constraints meant that working-class readers often favored literature of earlier periods, including the eighteenth century, which could be obtained in inexpensive popular editions, in secondhand bookstalls, in cheap reprints, or, as in Elgar’s case, by happenstance.

Certain of the composer’s biographers have seen Elgar’s interest in earlier literature as a mark of extraordinary intellectual curiosity, but a fascination with such authors was common among working-class autodidacts in the mid-nineteenth century.52 In the interview with The Strand Magazine in 1904 Elgar explains how he began to “read everything”:

I had the good fortune to be thrown among an unsorted collection of old books. There were books of all kinds, and all distinguished by the characteristic that they were for the most part incomplete. I busied myself for days and weeks arranging them. I picked out the theological books, of which there were a great many, and put them on one side. Then I made a place for the Elizabethan dramatists, the chronicles including Barker’s and Hollinshed’s, besides a tolerable collection of old poets and translations of Voltaire and all sorts of things up to the eighteenth century. Then I began to read. I used to get up at four or five o’clock in the summer and read—every available opportunity found me reading. I read till dark. I finished reading every one of those books—including the theology. The result of that reading has been that people tell me that I know more of life up to the eighteenth century than I do of my own time, and it is probably true.53

In an earlier interview with F. G. Edwards, Elgar relayed this story in a less vivid fashion but named titles: “In this way, he made the acquaintance of Sir Philip Sydney’s Arcadia, Baker’s Chronicles, Drayton’s Polyolbion, etc.”54 In “Elgar’s Use of Literature,” Brian Trowell wrote, “Edwards originally mentioned only Sir Philip Sydney” but Elgar added the rest of the list to the proof. Trowell opines that “these are indeed extraordinarily unlikely books for a fifteen-year-old to read, more a test of endurance than a literary experience.”55 Trowell misses a vital point, however, for an impecunious but voracious reader starved for material virtually any book will suffice, especially if nothing else is available. As Rose relates in his history, the self-educated Marxist author T. A. Jackson (1879–1955) testified that as an adolescent he read “Pope, old volumes from the Spectator, Robinson Crusoe, Pope’s translations of Homer, and a copy of Paradise Lost” for “the simple reason that there was nothing else to read.” Jackson later commented, in terms surprisingly close to those of Elgar, that “mentally speaking” he dated “from the early 18th century.”56 Rose further cites the memories of C. H. Rolph, who recalled that his father, a London policeman, read such books as “Aristotle’s Ethics, The Koran, Xenophon’s Memorabilia, the Nibelungenlied” as well as “Schiller’s William Tell.” After considering the effect of Xenophon on a London policeman of the Edwardian era, it is perhaps less difficult to imagine a young Edward Elgar devouring Sydney, Voltaire, and other authors more abstruse.

Ann Elgar’s reading may have included easily acquired classics, such as Alexander Pope’s translation of the Iliad, a volume that remained popular with working-class readers throughout the nineteenth century.57 Such an interest in these classic authors may account for Frank Schuster’s curious belief, told to Sassoon, that Elgar’s mother “used to sit up half the night reading Greek and Latin with him when a boy.”58 Whereas it is certainly true that some working-class readers did teach themselves Greek and Latin, it seems unlikely that a woman with a wayward husband and five children to feed, clothe, and educate had time to acquire the linguistic skills required to read Homer or Virgil in the original. In December 1874, Ann expounded upon the challenges of her situation: “It is no joke to have men and women to rule, and keep peace between, and to keep home in something [of] order and comfort.”59 Michael De-la-Noy is tartly dismissive of Schuster’s remark, implying that it was the result of a typically Elgarian exaggeration, but it is quite possible that Schuster was laboring under a misapprehension, since it seems unlikely that Elgar, even in his most self-mythologizing moods, would have concocted such an improbable tale. But it is entirely plausible that Elgar related to Schuster how his mother used to read translations of the Greek and Latin classics to him.60 Reading aloud was a major form of entertainment and edification in all kinds of households throughout the nineteenth century and, indeed, until the advent of radio broadcasting.61

However he may have found the literature of earlier eras, including the Greek and Latin classics, Elgar’s youthful interest in writers of earlier centuries—especially that of the previous one—resonated throughout his work. Has any other English composer since the death of Arne written so many minuets? These minuets, along with a light sprinkling of gavottes, appear throughout his career. Aside from the dedicated Minuet for Piano (1897; later orchestrated as op. 21), they appear in such disparate works as the Harmony Music no. 5 (1878), containing a minuet that Elgar reworked fifty-two years later for the Severn Suite, op. 87 (1930); the first Wand of Youth Suite, op. 1A (despite the fanciful opus number, this score dates from 1907); The Crown of India Suite, op. 66 (1912); and the incidental music to Beau Brummell (1928). Evocations of the eighteenth century occur in the Variations on an Original Theme, op. 36 (Enigma Variations, 1898–99)—Elgar once implied that the eighth variation, “W.N.,” was in part “suggested by an eighteenth-century house”—and consistently throughout his ballet, The Sanguine Fan, op. 81 (1917), the action of which unfolds in a rococo setting. Jerrold Northrop Moore writes: “The Sanguine Fan score opened with an ‘18th century theme’ (as the diary described it)—a courtly minuet elaborately descending.”62 (This four-measure minuet theme, usually presented as an antecedent phrase in search of a balancing consequent, permeates the entire work; it is treated almost like a ritornello throughout a substantial part of the score and is the source from which most of the thematic material is derived.) None of these minuets give off even the merest whiff of either irony or pastiche: Elgar’s musical antiquarianism was spontaneous, sincere, and informed by childhood memories.

Example 1. “Minuet” Theme, The Sanguine Fan, op.8, starting three measures after the opening.

One result of his unsupervised early reading may have been Elgar’s compulsion toward mystification.63 As part of this inner game, and to throw pursuers off his track, Elgar often sprinkled his manuscripts with epigraph “hints” from seemingly obscure sources such as Virgil, Tasso, Lesage, and others. It is not always apparent, however, that the composer was familiar with the entire book from which he quotes—or indeed where he may have found the epigraph in the first place. For example, the notoriously ambiguous line that Elgar affixed to the score of his Violin Concerto was drawn from Alain-René Lesage’s eighteenth-century picaresque novel, L’Histoire de Gil Blas de Santillane (1715–35; translated into English by Tobias Smollett in 1748 as The Adventures of Gil Blas of Santillane). Given its eighteenth-century provenance, and its translation by a noted English novelist of that period, Gil Blas would seem to fall firmly within the ken of Elgar’s literary enthusiasms; Brian Trowell has observed that this novel “was much better known in Elgar’s time than it is today,” an assertion that may well be true, but for which the author declines to offer even anecdotal evidence. Moore has pointed out, however, that this epigraph may have come to Elgar through the mediation of a contemporary poet, W. E. Henley, who quoted the same phrase—”Aquí estí encerrada el alma de …”—at the beginning of a volume titled Echoes.64 Did Elgar seek to appear more learned than he was, or was the temptation to expropriate a good mystifying quotation just too strong for him to resist?

The epigraph drawn from Ruskin’s Sesame and Lilies (1865) that Elgar inscribed on the full score manuscript of The Dream of Gerontius is another matter altogether, and points up the composer’s contradictory allegiances regarding his working-class origins. This epigraph is drawn from the first of the lectures that constitute Sesame and Lilies, Of Kings’ Treasuries,” section 9: “This is the best of me; for the rest, I ate, and drank, and slept, loved, hated, like another: my life was as the vapor, and is not: but this I saw and knew: this, if anything of mine, is worth your memory.”65 Unlike the ambiguity surrounding Gil Blas, Elgar had clearly read Sesame and Lilies: he had received this volume, along with Ruskin’s The Seven Lamps of Architecture, The Crown of Wild Olive, and others, as a gift from E. W. Whinfield in 1889.66 Induced by Charles F. Kenyon, a journalist who wrote under the pseudonym Gerald Cumberland, into recommending models of pure literary style, Elgar innocently cited Shakespeare, Ruskin, and Cardinal Newman.67 Elgar’s response to Cumberland thus places Ruskin in a triumvirate at the top of his pantheon.

Brian Trowell remarks that today it seems “not only odd, but disappointing” that Elgar declined to evoke Ruskin’s name during the course of the Peyton Lectures he gave at the University of Birmingham in 1905–6.68 But Elgar may have had cogent reasons for not quoting Ruskin directly, for as Trowell astutely observes, “Few people read Ruskin today, and it is curious how superficial our notions of ‘Ruskinian aestheticism’ have become… . In his own time, Ruskin was considered by many to be an unsettling and dangerous writer, or at best an impractical visionary.”69 Although Ruskin was admired by nearly all for his art criticism, his radical theories on political economy, including his comments on the need for a fixed wage for workingmen, were pilloried in the British press. The Saturday Review, for example, excoriated Ruskin’s political writings as “eruptions of windy hysterics … utter imbecility.”70 Ruskin’s plea in Sesame and Lilies for educational reforms designed to benefit workingmen and women, including for the establishment of “great libraries that will be accessible to all clean and orderly persons at all times of the day and evening” are far less startling than his suggestion that “maximum limits should be assigned to incomes, according to classes.”71 For voicing such progressive and compassionate sentiments, Ruskin, who put his educational beliefs into practice by teaching at the Working Men’s College, was revered by working-class readers.72

As Percy M. Young has noted, the public lecture itself was a tradition rooted in an ethic of Victorian adult education that had its roots in the working-class Mechanic’s Institutes—and Ruskin was widely considered the preeminent master of the public lecture. Even though Ruskin is not cited, Elgar’s Peyton Lectures are in essence a Ruskinian project. Young writes: “Elgar, the beneficiary of Victorian education and non-education, did not attempt to disguise a moral purpose, as is shown particularly by his loaded adjectives and his inspirational quotations from other writers… . Nor did he fail to draw attention to the responsibility that should be borne by those who controlled the nation’s wealth.”73 Elgar’s retentive memory allowed him to echo certain passages from Sesame and Lilies in both style and substance. Even the controversy engendered by Elgar’s lectures is reminiscent of how certain Ruskinian ideas were received by the popular press.

Although Elgar did not go so far as to suggest fixed incomes for the British populace—the very idea would have been abhorrent to him—some of the recommendations he made in the Peyton Lectures are like Ruskin’s in Sesame and Lilies. In the second lecture, “English Composers,” Elgar makes a number of sensible and enlightened suggestions, including his declaration, “I would like to see in every town—a large hall capable of accommodating a large sixpenny audience.” Reporting on this lecture, the Birmingham Post amplified Elgar’s remarks: “Sir Edward wished to see in every town a large hall capable of accommodating a large sixpenny audience, for the working classes, with their education, should be provided for as they were in Germany.”74 In a later lecture, Elgar declared forthrightly, “English working-men are intelligent: they do not want treating sentimentally, we must give them the real thing, we must give them of the best because we want them to have it, not from mere curiosity to see HOW they will accept it. What we do in literature and art, we might do in music.”75 Not only does this passage reflect the covert resentment of a man who had tasted the bitter cup of condescension based on class inequity, but it also represents Elgar’s internalization of the progressive educational reforms posited by Ruskin and other Victorian social reformers. Elgar’s call for inexpensive but dignified concert venues for working-class listeners is strikingly reminiscent of Ruskin’s utopian desire, articulated in Sesame and Lilies (“Of King’s Treasuries,” section 49) that “royal or national libraries will be founded in every considerable city, with a royal series of books in them … their text printed all on leaves of equal size, broad of margin, and divided into pleasant volumes, light in the hand, beautiful and strong.”76

Several reasons may account for the absence of references to Ruskin in the Peyton Lectures, the most obvious of which is that they have survived only as a series of fragmentary drafts: given the often incomplete and at times inchoate form of his lecture notes, it is impossible to assert that Elgar did not spontaneously invoke Ruskin at some point, as he did when speaking with Gerald Cumberland. (However, Ruskin’s name does not appear in any of the detailed accounts published in the Birmingham Post or any of the other reports included in Young’s painstaking, indeed heroic, edition of the Peyton Lectures.) But there may have been another reason why Elgar would have not felt altogether comfortable quoting Ruskin. By 1905, Ruskin may have been too obviously associated with the aspirations of workingmen and women and even too politically radical for Elgar, the former piano tuner’s son, to quote without suffering a queasy twinge of unsought self-revelation; in other words, Elgar may have suspected that citing Ruskin directly might recall to some minds the modest circumstances of his own birth and thus a declaration of literary and political allegiances to a lower class.77

Elgar was a consistent and devoted Tory in his political affiliations, and he strongly identified with the ruling classes whose ranks he sought to join, but a closer inspection of the seemingly impermeable facade of his con servatism reveals it to be riddled with small, almost reflexive, caveats. Elgar’s political sympathies were not unusual for a working-class autodidact of the Victorian and Edwardian periods: many members of the British working class during Elgar’s youth were conservative in their mores, cultural preferences, and often in their political views as well. Rose quotes Robert Roberts, who described British industrial laborers of this period as “Tory, royalist and patriotic.”78 Of those workingmen and women who leaned leftward in their political convictions at the beginning of the twentieth century, most might well have been described as Ruskinian socialists—only a highly vocal minority described themselves as communists.79

Elgar was hardly adverse to upward mobility, profiting as he had from the tenacious ambitions of his mother. Robert Anderson has noted that Ann “illustrated her teachings with an extract on ‘Vulgar People’: ‘Being poor is not of itself a disqualification for being a gentleman. To be a gentleman is to be elevated above others in sentiment rather than situation.’”80 This extract voices a conviction held by many working-class autodidacts: the elevated sentiment often achieved by a refinement of the intellect was not just a monopoly of the upper classes but could be cultivated by any questing mind, regardless of birth.81 To succeed among the wealthy, however, it was best to combine elevated sentiment with either dim perception or unlimited generous forgiveness, neither of which attributes Elgar possessed in any degree. His incessant social climbing, often unfairly laid at the feet of his wife, who was born into a markedly higher class than her husband, may have been an attempt to mitigate feelings lacerated by a thousand small but precisely remembered indignities. Despite his bent for self-pity and exaggeration, Elgar’s vexation at perceived cuts and insults may often have had a tangible basis, as such social checks were the main machinery that kept the Victorian and Edwardian hierarchy in working order, besieged as it was by newcomers.82 Elgar was a prime candidate for expulsion on at least three counts: his working-class origins, his circumscribed formal education, and his Roman Catholicism. Any of these factors might have barred him from assuming the prerogatives that were jealously guarded by the Victorian and Edwardian upper classes, but Elgar had a card up his sleeve to trump the social game so evidently stacked against him: his prodigious talent. And though Elgar’s talent did in fact help him into a higher class status, its magnitude could never entirely allay the composer’s insecurity about his new social standing—especially among those so entirely devoid of talent themselves.

From early years, Elgar was possessed by a longing for reassurance that could never be assuaged fully, even by his patient wife. No honor was ever enough to mitigate his feelings of exclusion from the upper classes—even when, to all appearances, he had joined them. Elgar’s simmering class-based anger was always on the verge of boiling over. Asked in 1922 to contribute toward a frivolous project—a dollhouse for Queen Mary—Elgar responded with a tirade. As Sassoon recorded in his diary:

The subject provoked an outburst from Elgar; he delivered himself of a petulant tirade that culminated in a crescendo climax of rudeness aimed at Lady M[aud Warrender] (who is a fashionably-attired Amazon with a talent for singing and archery; quite a noble creature, and extremely amusing). “I started with nothing, and I’ve made a position for myself!” ejaculated the Order of Merited composer who masquerades as a retired army officer of the conservative club type. “We all know that the King and Queen are incapable of appreciating anything artistic; they’ve never asked for the full score of my Second Symphony to be added to the Library at Windsor. But as the crown of my career I’m asked to contribute to—a DOLL’S HOUSE for the QUEEN!! I’ve been a monkey-on-a-stick for you people long enough. Now I’m getting off the stick.”83

Though this outburst makes for sorry reading, it contains a distant echo of Ann Elgar’s wholly admirable resistance to discrimination based on rank, contained in her opinion, similar to that of Cardinal Newman, that the status of “gentleman” is independent of birth or wealth and can be acquired through self-improvement. Sassoon, an outsider himself in British society due to his Jewish father and homosexuality, but nevertheless born to privilege, snickered at the idea of a famous composer who “masquerades as a retired army officer” making such a fuss over a dollhouse. But Sassoon missed the tension that lay beneath Elgar’s truculence: an insult to his honor, his talent—the reason for the composer’s almost Ruskinian contempt of the inartistic hereditary aristocracy and his impassioned cry, “I started with nothing, and I’ve made a position for myself!”

Brian Trowell has described Elgar as “a progressive” Conservative whose “politics were instinctive and emotional, not intellectual, and appear to have sprung from a romantic and escapist identification with the great Tory families of Queen Anne’s reign, many of whom were Catholic and even Jacobite in their sympathies.”84 Trowell neatly encapsulates the paradox of Elgar’s political convictions by modifying his characterization of the composer’s Tory allegiances with the appellation “progressive.” While surely most political convictions are “instinctive and emotional, not intellectual,” to suggest that Elgar’s political beliefs had their origins solely in an “identification with the great Tory families of Queen Anne’s reign” is to court oversimplification. Elgar was far from “progressive” on occasion, as when he shamefully resigned from the Athenaeum to protest the election to that select establishment of Ramsey MacDonald, a working-class autodidact much like himself and the first Labour prime minister.85 Elgar was capable of behaving in a patronizing manner to members of the working class, but he is hardly the only man who—having struggled past the doorman—has to turn and defend the door by which he has just entered. Despite his penchant for weaving a potent mythology about his origins, Elgar was never so deluded as to deny his past, however much he may have embroidered it. Even when he assumed the borrowed plumage of an “English gentleman,” which for a piano tuner’s son from Worcester may have ineluctably led to Tory convictions, Elgar never tried to efface the basic outlines of his youth, which he retailed often, in detail and publicly. Elgar sought to eat his cake and have it: not only did his natural gifts allow for spectacular upward mobility from his working-class origins (“I’ve made a position for myself”), but his internalization of his mother’s definition of a “gentleman” may have convinced him that he was entitled to that exalted position by right, thus transcending the otherwise intractable barriers of birth and formal education. Elgar’s Ruskinian progressivism, which doubtless assumes poignancy when viewed in light of his own history, had little to do with the Tory politics worn like an expensive tweed suit by this English gentleman. Rather, Elgar’s politics testified to his status as an autodidact whose origins were firmly rooted in working-class soil.

On the Beautiful in Music

Every object that emerges into the focus of attention has meaning

beyond the “fact” which it figures.

—Suzanne Langer, Philosophy in a New Key, 1942

Viewing Elgar’s literary taste and political affiliations from the perspective provided by the traditions of working-class autodidacts illumines both his psychological development and his choice of texts. In addition, a study of Elgar’s instrumental music and aesthetics benefits from an investigation of the peculiar ways in which memory functions for self-learners. Cognitive scientists have conducted surprisingly little research into autodidacticism. However, a recent book edited by the British educational researcher Joan Solomon, A Passion to Learn: An Inquiry into Autodidacticism, sheds some light on this unaccountably neglected subject. Consisting of fourteen case studies of self-learners, Solomon’s book touches upon such topics as the effect of emotion upon learning, the importance of self-motivation, and, crucially, the sense of a life mission that often is manifested early in life. Solomon eloquently describes autodidacts as “frequently emotional, strongly autonomous, passionate, and future-orientated”—traits that were conspicuous facets of Elgar’s personality as well.86

As Solomon carefully documents, learning acquired by autodidacts early in life exercises a peculiarly strong influence throughout their later lives; ways of remembering are thus of paramount importance to later success. Citing the research of the Canadian psychologist Endel Tulving, Solomon writes: “The present understanding of memory defines it in three quite different modes of operation.” She later summarizes the three modes of memory:

The semantic memory relies on remembered abstract conceptual words that need to be applied in a new context. Procedural memory is remembered non-verbally in our bodies where it was first practiced. Tulving’s special new contribution was episodic memory. This is the familiar way in which we recall a whole incident complete with perceptions (including smells), cognition (if we were learning or experiencing) and emotional reactions which make up motivation (horror, delight, curiosity, etc.)… Looked at in another way we may see that emotion and cognition are, after all, not so very different.87

All of these ways of remembering might be relevant to a study of Elgar’s musical life. Procedural memory—lodged in the somatic memory—allowed Elgar to learn to play the violin and become a celebrated conductor. Episodic memory is exemplified by the way in which the young violinist in Worcester who played Hérold’s Zampa Overture fastened it in his memory well enough so that hearing a passage from Brahms’s Third Symphony enabled him to recall Hérold’s score and thus make a telling connection between overture and symphony in the third Peyton lecture delivered in Birmingham.88 The mode that will be the primary focus of this line of investigation, semantic memory, permitted Elgar to remember in minute detail certain abstract concepts learned early in life that he would transform over the course of his career: an abstract concept such as a system of key symbolism, for example, may well have become a building block for his formal procedures as well as a stylistic trait. In semantic memory, an abstract concept once learned may be reinterpreted, but retains something of the integrity of the first encounter.

As is clear from Rose’s study and Elgar’s biography, autodidacts are voracious readers whose exceptional memories retain an astounding amount of what they have read in remarkable specificity. Equally evident from Elgar’s Peyton Lectures is that he shared an unfortunate characteristic common to many autodidacts, a problem that surfaces frequently throughout their lives. Because autodidacts teach themselves without outside guidance, the knowledge they amass often contains odd lacunae even within an otherwise detailed body of information about a subject that interests them passionately. Misconceptions that could have been corrected easily by more systematic pedagogy can persist well into middle or even old age. Elgar became an expert violinist due in part to his lessons with the noted virtuoso and pedagogue Adolphe Pollitzer. In contrast, after a few lessons in childhood, his exploration of the piano was essentially unguided. Violinists praise his expert writing for strings, but many pianists who have performed Elgar’s music remark that his writing for the instrument is often idiosyncratic and cannot be characterized as “pianistic.”

Although Elgar expressed a healthy skepticism concerning the texts he used to educate himself as a boy—and he dismissed the textbooks of Charles-Simon Catel and Luigi Cherubini as “repellant”—the influence of the books in his youthful library cannot be overestimated.89 As previously noted, indigent autodidacts read and remembered the driest of texts if those books were the only ones available; Rose quotes working-class readers who testified that they read avidly such unappetizing tomes as algebra treatises, “back numbers of the Christian World,” and, in one dire instance, “a Post Office Directory for 1867, which volume I read from cover to cover.”90 Next to these, textbooks by Cherubini, John Stainer, and Catel seem alluring, if not downright racy. These volumes, which the composer kept over the course of his life and which are now housed in the collection at the Elgar Birthplace Museum, are the pillars upon which rests the edifice of Elgar’s musical self-education: he devoured them, read them critically, annotated them, and tenaciously stored them in his memory.

The adolescent Elgar must have turned with relief from the strictures of Cherubini and Stainer to Berlioz’s enthralling Treatise on Modern Instrumentation and Orchestration as well as to the invitingly poetical books by Ernst Pauer. Pauer was an Austrian composer, pianist, and pedagogue who settled in England in 1870, teaching piano first at the Royal Academy and then, in 1876, at the National Training School for Music, the precursor of the Royal College of Music. Noted for presenting a series of historical recitals that spanned keyboard music from 1600 to the present—he used a harpsichord for the earlier items—Pauer was a respected presence on the British musical scene until his retirement to Germany in 1896.91 Elgar possessed two of Pauer’s little books, which are primers rather than textbooks, both published by Novello. Pauer’s Musical Forms (author’s preface dated 1878) is a brief general survey of basic formal designs such as the sonata and the variation; The Elements of the Beautiful in Music (author’s preface dated 1877) is an exuberantly Romantic exegesis of music aesthetics.

The Elements of the Beautiful in Music is the sole treatise on aesthetics that has survived from the young composer’s library and may well have had an even greater impact on his compositional development than Pauer’s admirably lucid explanation of musical form. The title page is stamped “Elgar Brothers Music Sellers, Worcester,” so it was in Elgar’s hands early. That the adolescent Elgar, who signed the title page with his customary bold script, attentively read The Elements of the Beautiful in Music is evident in two instances of penciled underlining.92 Pauer’s book would have been attractive to Elgar for several reasons, not the least of which is its exalted tone, strongly reminiscent of Ruskin in passages—not to mention of Longfellow’s Paul Flemming. Pauer shares with Ruskin a philosophical viewpoint that might be termed “Romantic Platonism,” an aesthetic whose emphasis on striving for the ideal and espousing high moral values chimed with the young Elgar’s musical and literary predilections. Ruskin writes in The Queen of the Air (section 42) that music is “the teacher of perfect order and is the voice of the obedience of angels and the companion of the course of the spheres of heaven.”93 He surely would have agreed with Pauer’s assertion that “it is evident that religion and art are closely connected,” not to mention the Austrian’s belief that “art has to exhibit to humanity the ideal picture of what perfect human beauty can be.”94

Despite the similarity of their titles, Pauer’s book has little in common with Eduard Hanslick’s 1854 volume, Vom Musikalisch-Schönen (On the Beautiful in Music). Sharing only a broad debt to German philosophy, Pauer is closer to the critical writings of Schumann than the austere Hegelianism of Hanslick.95 Indeed, Hanslick poured scorn on the very writers, such as Schumann, who served Pauer as exemplars; the Viennese music critic castigated such authors—and doubtless would have included Pauer in this company—as deluded Romantics who wrapped discussions of music “in a cloud of high-flown sentimentality.”96 Judging by an excursus found in the fifth Peyton lecture, titled “Critics,” Elgar had read at least some Hanslick with care and, as Trowell has observed, shared with the Viennese music critic an unease, common to certain other composers of the period, about music’s “‘poetical-pictorial’ associations.”97 But Elgar shrewdly deconstructs Hanslick’s seemingly uncompromising aesthetic stance by pointing out an inconsistency. Elgar quotes the critic’s assertion, embedded in a review of Brahms’s Third Symphony—“Spoken language is not so much a poorer language as no language at all, with regard to music, for it cannot render the latter”—but then remarks, “Hanslick allows himself to call the opening theme of the last movement ‘a sultry figure’ foreboding a storm.”98

Unlike Hanslick, however, Pauer was perfectly at ease making sweeping generalizations about such high-toned but vague concepts as “tone-painting,” “ideal beauty,” “truth,” and the “infinite.” Pauer’s frequent evocations of the “ideal” put him squarely in the tradition of German Romantics; he quotes from both Schelling and Schiller and cites Plato, Aristotle, Pythagoras, Kant, Ferdinand Hand, and Hegel in his preface. Such vocabulary would have set Hanslick’s teeth on edge and seems quaint today. But some of Pauer’s statements—such as “uneducated intellects will never reach the pure heights of perfection”—may have deeply resonated in a boy with aspirations, trapped in modest circumstances with few obvious prospects, who was doggedly reading Pauer in pursuit of the “mystery” of music.99

Pauer does not stop at exhortation: in detailed affective descriptions of each of the major and minor keys he posits a theory of keys. By so doing, Pauer is part of a long tradition that includes Kirnberger and other eighteenth-century German theorists who speculated on the relationship of keys and temperament within the context of Affektenlehre.100 Berlioz compiled a description of keys in his Treatise on Modern Instrumentation and Orchestration, a text well-known to Elgar, but Berlioz is exclusively concerned with the intersection of keys with instrumental technique. Rimsky-Korsakov’s unsystematic association of key areas with color would seem at first to be close to Pauer’s characterizations, but there is a crucial difference between the two: Pauer uses an affective vocabulary while the Russian composer veers into the realm of synesthesia. Rimsky-Korsakov’s disciple V. V. Yastrebtsev recorded in his diary that “the various keys suggest various colors, or rather shades of color, to Rimsky-Korsakov… for example, E major seems tinged with a dark blue, sapphire-like color.”101 The point is not whether Kirnberger’s theory, or Rimsky-Korsakov’s system, or Pauer’s associations for key centers are objectively “correct,” or that they may contradict other such systems, but that Pauer’s theories may have meant something to Elgar and may have influenced, consciously or unconsciously, his choice of keys in certain of his scores. If Pauer’s designations for keys did influence Elgar—and there is reason to suggest they did—then surely this is a powerful instance of semantic memory, as the English composer would have constantly returned to a set of abstract ideas throughout his life, reinterpreting them while still retaining something of their original import.

Through Pauer’s descriptions, the various keys evoke certain moods and mental states such as innocence (C major), sadness (C minor), and dreamy melancholy (G minor).102 Pauer’s hypotheses are presented with a peculiarly Teutonic mixture of thoroughness and sentiment as he asserts: “In music, the innermost feelings of the composer are displayed; and in so far as the characteristic is founded on the individual or personal feeling, an original composition must in itself be characteristic… . The characteristic shows itself by means of the tones and intervals, and finds expression through the minor and major keys, through the time and movement, through the accent, the rest, the figures, and passages and last, but not least, through the melody.” Pauer declares that “the proper choice of key is of the utmost importance for the success of a musical work; and we find that our great composers acted in this matter with consummate prudence and with careful circumspection.” Pauer is careful to offer a caveat to his characterizations of the different tonalities by noting: “It cannot be denied that one composer detects in a certain key qualities which have remained entirely hidden from another… . We lay down a rule which admits many exceptions… . All we can safely do is to name the characteristic qualities of the keys as we deduce their characteristic expression from universally admired and accepted masterpieces: and thus we need not fear to misstate or to misapprehend the bearing of the subject.” Further, he takes the precaution of recommending variety through modulation: “When the composer has chosen his key, he will be careful to handle it in such a manner that it does not attain too great a prominence, which would result in monotony, and cause fatigue and lack of interest in the listener; but he will manage to suffuse his work with the special characteristics of the key, which is thus made to glimmer or shine through the piece without asserting itself with undue strength.”103

Pauer’s assertions, including his descriptions of each key, might seem a charming but inconsequential byway of Romantic aesthetics were it not for the autodidact from Worcester with the fantastically retentive memory. For those who have even a glancing acquaintance with Elgar’s music, Pauer’s descriptions are suggestive. According to Pauer, “D major expresses majesty, grandeur, and pomp, and adapts itself well to triumphant processions, festival marches and pieces in which stateliness is the prevailing feature.”104 After the first Pomp and Circumstance March—famously in D major—ceases to ring in the reader’s ears, the question naturally arises: How often do Pauer’s discussions of keys tally with Elgar’s music? Such a study would be informative if one bore in mind that not even a slavish dedication to Pauer and his ideas would result in a complete match between Elgar’s key selection and Pauer’s characterizations, since Pauer left room for inventiveness and creativity—and that the ambitious young Elgar would have felt he possessed both. The point is not whether Elgar consciously planned out his works to conform to Pauer’s descriptions—an improbable hypothesis at best, as there are instances where Elgar’s music contradicts the Austrian’s characterizations—but rather how his tenacious memory may have colored certain musical decisions as a result of his early reading.

So, though it is certainly too fanciful to suggest that Elgar designed the complex key relationships of The Dream of Gerontius so that the supernal opening of the second part would conform to Pauer’s description of F major as a key full of “peace and joy … but also express [ing] effectively a light, passing regret … [and], moreover, available for the expression of religious sentiment,” it is, however, worth remarking that this is the only extended passage in F major in the entire score.105 Was Elgar’s reading of Pauer a seminal factor in the composer’s choice of key? Nothing in the elaborate key structure of Gerontius, which, Elgar’s sketches show, was planned early in the score’s genesis, required that this particular crucial moment be cast in F major. In other words, tonal logic alone cannot explain why Elgar selects keys for certain expressive contexts.

A striking instance of a key that seems to act as a particularly potent signifier for Elgar is that of E-flat major, which Pauer describes as a “key which boasts the greatest variety of expression.” Pauer continues, remarking, “At once serious and solemn, it is the exponent of courage and determination, and gives to a piece a brilliant, firm and dignified character. It may be designated as eminently a masculine key.” Pauer often draws his examples from Beethoven, whom he praises as “the composer whose works may be taken pre-eminently as a type of ideal beauty.”106 That Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony in E-flat Major looms large behind Pauer’s characterization of this key cannot be doubted, although as a pianist, Pauer may have also had in mind the Emperor Concerto, cast in the same key as the symphony.

To follow Elgar’s use of E-flat throughout his mature music would be a revealing exercise, but discussion here will be restricted to five major works composed over thirteen years: the Enigma Variations; the concert overture In the South (Alassio) (1903–4); the Second Symphony (1911); The Music Makers (1912); and, finally, his “symphonic study,” Falstaff (1913). Of these scores, In the South and the Second Symphony share E-flat major as the dominant tonality; the “Nimrod” variation from the Enigma Variations is cast solely in that key; the fifth stanza of The Music Makers begins in E-flat; and a single theme from Falstaff cast in E-flat will be discussed. All of these scores have masculine associations; four of these works specifically evoke two of Elgar’s closest male friends.

The “Nimrod” variation, the climactic ninth of thirteen, is the emotional and structural climax of the Enigma Variations, and portrays Elgar’s loyal friend August Jaeger.107 One of the curiosities of Pauer’s book that could be related to the use of E-flat major for this heartfelt music is that the Austrian author does not merely characterize key centers, but time signatures as well. Pauer thus declares triple time to be expressive of “longing, of supplication, of sincere hope, and of love… . It possesses a singular tenderness and a remarkable fund of romantic expression.”108 Inquiry into a composer’s creative process can only be speculative, but it is striking that Pauer’s descriptions of key and time signature constitute a virtual recipe for the “Nimrod” variation, surely one of the most moving evocations of the intense tenderness that can lie at the heart of male friendship.

Example 2. Opening Measures, “Nimrod” variation, Variation IX of the Enigma Variations, op. 36, starting at rehearsal number 33.

Example 3. Recall of the “Nimrod” variation from the fifth stanza of The Music Makers, op. 69, starting at rehearsal number 51.

Elgar explicitly connected both his concert overture In the South and the Second Symphony to his friend and faithful patron Frank Schuster, the homosexual son of a wealthy banker. Siegfried Sassoon, in an otherwise venomously penned portrait of Schuster, noted that his erstwhile friend’s “hero-worship of Elgar was (justifiably) the most important achievement of his career, because he really did help Elgar toward success and recognition.”109 Schuster tirelessly promoted Elgar’s music in aristocratic and artistic circles, and, as Sophie Fuller discusses elsewhere in this volume, Schuster’s elegant home in London and his country house, The Hut, in Bray-on-Thames, were important sites for Elgar, who occasionally used the estate as a refuge when composing. Elgar trusted Schuster so explicitly that he designated his patron as one of his daughter’s guardians when the composer and his wife left for America in 1905.110 Even death did not fully curtail Schuster’s generosity, for he left Elgar the considerable sum of £7,000, writing in the bequest that the composer had “saved my country from the reproach of having produced no composer worthy to rank with the German masters.”111 Elgar was deeply saddened by his patron’s death, writing to Schuster’s sister, Adela, “By my own sorrow—which is more than I can bear to think of at this moment (a telegram [announcing Schuster’s death] has just come) I may realize some measure of what this overwhelming loss must be to you.”112

Elgar dedicated In the South to Schuster. The composer wrote that his friend would find the overture filled with “light-hearted gaiety mixed up in an orchestral dish [in] which [,] with my ordinary orchestral flavouring, cunningly blent, I have put in a warm cordial spice of love for you.” In the South, inspired, as the title attests, by a journey to Italy, was completed barely in time for the premiere, which took place on the third evening of a festival devoted to Elgar’s music.113 In a remarkable show of devotion, Schuster offered practical proof of his admiration by underwriting this ambitious undertaking, in effect assuming responsibility for any financial loss that might have occurred.

Elgar wrote to Percy Pitt that the opening of In the South portrayed “the joy of living” and had an “exhilarating out-of-doors feeling.” The overture’s initial theme was originally jotted down as a musical depiction of the “moods of Dan” in 1899—Dan was a boisterous dog belonging to Elgar’s friend George Robertson Sinclair—and was cast originally in E major.114 Robert Anderson aptly observes that the example of Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben may have induced Elgar to transpose this theme to E-flat major, but, as we shall see, there may well have been another reason for this change. The broader questions of why Elgar projected human emotions onto a dog and how this anthropomorphic projection called forth such varied and expressive ideas are unanswerable, though the surprisingly varied “moods of Dan” themes are suited perfectly to the scores in which they appear.115

Shortly after Schuster’s death in 1928, Elgar wrote to Adela Schuster, who had requested of the composer an epitaph for her brother: “I want something radiant, bright & uplifting for dear Frankie’s memorial stone & I cannot find it: forgive me I have failed. I have said in music, as well as I was permitted, what I felt long ago,—in F[rank]’s own Overture ‘In the South’ & again in the final section of the Second Symphony—both in the key that he loved most I believe (E flat)—warm & joyous, with a grave and radiating serenity: this was my feeling when the Overture was dedicated to him 24 years ago & is only intensified now.”116 Did Elgar transpose the opening theme of In the South from its original E major to E-flat major in part because he knew that Schuster “loved” the lower key? As Elgar designed the overture as a special gift to Schuster, a friend who relished all manner of male company, one can only speculate whether or not, lurking in back of his mind, there might have been a persistent wraith of memory of Pauer’s description of E-flat major as “masculine.” By far the most interesting aspect of Elgar’s letter to Adela Schuster, however, is that as late as 1928 his characterization of E-flat major is reminiscent in style of Pauer’s affective vocabulary—“the exponent of courage and determination, and gives to a piece a brilliant, firm and dignified character.”

Elgar’s Second Symphony has been associated with any number of the composer’s friends and acquaintances. Often mentioned is Edward VII, to whose memory the work is dedicated.117 Lady Elgar invoked Alfred Rodewald, whose death in 1903 deeply agitated her husband, as an inspiration for the harrowing slow movement.118 Elgar himself declared that a theme in the last movement was a portrait of Hans Richter: “Hans himself!”119 Alice Stuart-Wortley has been construed as a muse for the symphony through readings—of variable insight depending on the interpreter—of the composer’s letters to her.120 Frank Schuster is rarely mentioned, however, despite Elgar’s clear statement that the symphony’s poetic coda, cast in E-flat major, was inspired by him. One wonders if Elgar ever mentioned his intention to Schuster, who was very much alive in 1911 when this symphony in his favorite key was premiered. Once again, Elgar provided a motto for the symphony that has given rise to much speculation, the first line from one of Shelley’s poems: “Rarely, rarely comest thou, / Spirit of Delight!”121 Describing this score, throughout which E-flat major glimmers and shines, Elgar wrote to his publisher in terms that conjoin his 1928 letter to Adela Schuster with Pauer’s characterization of E-flat major, for, he confided, “The spirit of the whole work is intended to be high & pure joy: there are retrospective passages of sadness but the whole of the sorrow is smoothed out & ennobled in the last movement, which ends in a calm & I hope & intend, elevated mood.”122

Example 4. Excerpt from the coda of the Finale, Symphony no. 2 in E-flat major, op. 63, five measures after rehearsal number 170.

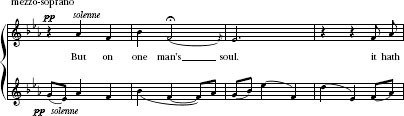

The Music Makers, a setting of an ode by the poet Arthur O’Shaughnessy (1844–81) for mezzo-soprano, chorus, and orchestra, was finished a year after the first performance of the Second Symphony. The poem expresses an earnest, striving ideology reminiscent of Longfellow’s more exhortatory poetry, as well as a high vision of the artist’s calling that recalls the American author’s Hyperion. Here, however, as Aidan J. Thomson has observed, Elgar deconstructed O’Shaughnessy’s poem by using quotations from his own scores, creating an agonistic relationship between the text’s optimism and the music’s repeated tendency toward pessimistic dissolution. Semantic memory thus assumed a crucial role in the creation of The Music Makers: Elgar treated themes from previously composed works as abstract entities thrust into a wholly new context, yet still retaining something of their original import. The Music Makers is surely the most self-referential of Elgar’s autobiographical scores; of this work, he wrote to Ernest Newman, “I am glad that you like the idea of the quotations: after all art must be the man, & all true art is, to a great extent egotism & I have written several things which are still alive.”123

Example 5. Quotation from the coda of the Finale, Symphony no. 2, in The Music Makers, starting at rehearsal number 53.

The Music Makers may furnish further evidence of Schuster’s connection to the Second Symphony. In the most protracted allusion in the score, Elgar uses the “Nimrod” variation to illustrate lines in O’Shaughnessy’s fifth stanza, which reads in part: “But on one man’s heart it hath broken, / A light that doth not depart; / And his look, or a word he hath spoken, / Wrought flame in another man’s heart.”124 Of this passage Elgar testified, “Here I quoted the ‘Nimrod’ Variation as a tribute to the memory of my friend, A. J. Jaeger: by this I did not mean to convey that his was the only soul on which light had broken or that his was the only word, or look, that wrought flame in another man’s heart.”125 For this tribute to Jaeger, Elgar not only quotes the “Nimrod” variation, but begins this stanza in the variation’s key of E-flat major as well, making this the only quotation in The Music Makers that appears in its original key.126 (After the initial statement of the “Nimrod” theme, this section vacillates between E-flat major and A-flat major—Pauer describes this key as “full of feeling and replete with a dreamy expression”—before finally settling into the latter.)127 Since the key scheme in The Music Makers is as intricate as any other of Elgar’s major works, the composer may well have designed the tonal plan to accommodate this excursion in E-flat major. As Moore notes, the recall of the “Nimrod” variation “dwarfed all the short surrounding Music Makers figures—especially when ‘Nimrod’ found a wonderful coupling with the final descending figure from the Second Symphony in the same key.”128

As mentioned earlier, Elgar told Adela Schuster that he had portrayed her brother in the coda of the Second Symphony, the pervading theme of which is Moore’s “descending figure.” Was Schuster one of the men, along with Jaeger, whose word or look “wrought flame in another’s man’s heart”? And did Schuster, whose favorite key of E-flat is common to all this music, have an inkling of Elgar’s tribute in the symphony’s coda and, thus, in The Music Makers? As Diana McVeagh once exclaimed, “If [Elgar] genuinely disliked people wondering about his private life, why had he not learned his lesson from ‘enigma’? To cap it all, he composed The Music Makers, with its allusions and references, many of which could not be fully understood by anyone who know nothing of his past life.”129

But not all of Elgar’s self-revelations were made consciously. In his “symphonic study” Falstaff, the theme that, according to the composer’s own description, portrays Prince Hal in “his most courtly and genial mood” is cast in E-flat major. Unlike the “Nimrod” variation, the Second Symphony, or The Music Makers, a fictional character is portrayed in Pauer’s “eminently” masculine key in Falstaff. Although a full analysis of Falstaff is beyond the scope of this essay, it can be pointed out that this first Prince Hal theme undergoes a development both psychological and musical, since its apotheosis (rehearsal number 127) represents the royal progress of Prince Hal, just crowned as Henry V, and occurs just before his ruthless repudiation of Falstaff: “How ill white hairs become a fool and jester!” (2 Henry IV, 5.5.41, 46).130

Example 6. Prince Hal as “courtly and genial,” Falstaff, op. 68, starting at rehearsal number 5.

Whereas some Shakespearean scholars have discerned a homoerotic bond between Prince Hal and Falstaff—one that the new king must break decisively to assume full authority—others, such as Stephen Greenblatt, have viewed this relationship as one between a failed surrogate father and a son who must repudiate his “false father” to reach maturity. (Given the seemingly limitless levels of meaning in Shakespeare, both may be equally valid.) Greenblatt writes that Shakespeare may have had his own father, John, in mind when he created Falstaff, whose “fantasies about the limitless future” invariably “come to nothing, withering away in an adult son’s contempt.”131 Given Elgar’s uncanny ability to project his imagination into the souls of others, whether actual or fictional, is it possible that while he re-created Shakespeare’s Falstaff in his own image, he also secretly identified with Prince Hal, who, despite unpromising beginnings, achieves majesty?132 Did not Elgar reject his own father, who, according to his scornful son, “never did a stroke of work in his life”? Schooled by his mother to discipline—or repress—his emotions through voracious reading and incessant self-learning, Elgar assumed the mantle of a man of “stern reality” who in 1885 displaced his father as organist at St. George’s, and then progressed royally to fame, an honorary doctorate at Cambridge, knighthood, the Order of Merit, and other coveted honors.133

Any composer’s creative process is shrouded in an impenetrable mystery, and the last thing that can be expected of any artist is a foolish consistency. It is clear that Elgar’s early reading, encouraged by his mother, made him into a lifelong autodidact; her literary tastes informed his own, and those tastes influenced his choice of texts. More mysterious are the ways in which Elgar’s retentive memory enabled him both to reflect and to transform the humdrum realities of his youth into imperishable works of art, and thereby transcend the unpromising circumstances of his birth. Elgar certainly took full advantage of the creative freedom evinced by Pauer’s “great composers” and never espoused a systematic approach to any part of the “mystery” of music. However much the autodidact from Worcester may have retained and transformed Pauer’s theories in the vast storehouse of his memory, certain of that author’s observations, when read in light of Elgar’s achievement, assume the force of prophecy: “He who aims at the greatest, the highest, must summon all his strength… . Art has to exhibit to humanity the ideal picture of what perfect human beauty can be.”134

NOTES

The author wishes to thank Charles Edward McGuire, John Lowerson, Lauren Cowdery, Eric N. Peterson, Paul De Angelis, Howard Meltzer, Conrad Susa, and Chris Bennett for their help in the completion of this essay, which is dedicated to Diana McVeagh.