Elgar and the British Raj:

Can the Mughals March?

NALINI GHUMAN

Sir Edward Elgar touches us at home by his declared intention to write a “musick masque” on the theme of the “Crown of India,” and make it celebrate the “pomp and circumstance” of the Imperial Coronation Durbar … India has lavished her arts of splendour on the Royal visit, and it is only fitting that a great master in the West should spend the wealth and range of his powers on interpreting for us “the kingdom, the power, and the glory” of the highest manifestation of empire that the world has seen.

—Pall Mall Gazette, 9 January 1912

In January 1912, at the height of its imperial fervor, the British public eagerly devoured colorful newspaper reports of King George V’s visit to India the previous month.1 This royal visit celebrated the king’s assumption of the title “Emperor of India” that had been bestowed upon him during his coronation in Westminster Abbey on June 22, 1911. The focus of the new king’s Indian sojourn was the Delhi “Durbar,” the court ceremony held in his honor in December 1911, and presented in “Kinemacolour” film to packed London picture houses the following year. A magnificent imperial occasion lasting some ten days, the Durbar involved over 16,000 British and 32,000 Indian officials, and displayed the obeisance paid by all the Indian princes to their rulers.2 An Australian visitor marveled at “the pomp and solemnity of it all; the gorgeous hues … the rhythmic march of regiments; the masses of white-robed, keen-eyed natives; the blended colours where East and West met … the thousand sights seen beneath the glamour of that old Indian sun.”3 The event was widely reported and attracted praise from all corners of the empire.

Contrary to appearances and popular belief, however, the Durbar was more than a “pageant of splendour,” as one spectator termed it.4 It afforded an opportunity for the king-emperor to announce several crucial measures to bolster England’s weakening hold on India. The first, the shift of the imperial capital from Calcutta to Delhi, had been the subject of debate, and the suitability of other cities as capital had been considered. The kingemperor’s second announcement was, in the words of an American spectator, “surely the best-kept secret in history … it literally took away the breath of India.” He announced the reunification of Bengal, repealing Lord Curzon’s partition of the region in 1905 as part of the English “divide and rule” policy.5 The partition repeal was reportedly “fraught with such vast import” that the king’s announcement left “astonishment and incredulity on every face.”6

In 1905 Curzon, then the viceroy, had split Bengal down the middle, creating Eastern Bengal and Assam, which included the Muslim-majority eastern districts.7 This arbitrary division caused seven years of communal violence and bloodshed among the Hindu and Muslim populations of Bengal, along with a sharp rise in anticolonial activity and general political anarchy.8 Hindi Punch sought to convey the gravity of the 1905 partition in a cartoon entitled “Vandalism! Or, The Partition of Bengal!” that featured a woman (representing Bengal) who has been chopped by an ax into pieces that represent Assam and East Bengal (figure 1).9 The tumult surrounding the partition had marred George’s reception in India as Prince of Wales in 1905 and led him to conclude that the decision had been a serious political error. The repeal, advocated by George V, was agreed upon after a year of secretive debate concerning “the partition crisis,” as the home secretary put it, in which British officials “surveyed the widening cracks in the wall of British authority as a consequence of five years of chaos.”10 The Delhi Durbar thus provided “a unique occasion for rectifying what is regarded by Bengalis as a grievous wrong.”11 But the repeal also signaled the beginning of imperial disintegration, for the partition decision had provided the needed catalyst for effective Indian resistance.12

Masking the Durbar

The Durbar, whose Indian memorial will be the buildings of the new capital, is to be commemorated in England by a masque composed by Sir Edward Elgar.

—The Globe, 9 January 1912

To mark the occasion of the Delhi Durbar, Elgar collaborated with Henry Hamilton on The Crown of India, an “Imperial Masque” produced by Oswald Stoll at the London Coliseum and performed in a mixed music hall program that opened on March 11, 1912.13 The Crown of India was advertised by the London Times as “a project which will evoke extraordinary interest and will, no doubt, prove, under Sir Edward Elgar’s treatment, worthy of the historic event that it is designed to commemorate in so graceful a fashion.”14 Not only graceful, but also elaborate: production costs exceeded £3,000, a huge sum at the time, with ornate costumes and lavish settings by Percy Anderson; after all, the Daily Telegraph remarked, “so vast and dazzling a subject cannot, obviously, be treated in the spirit of parsimony.”15 And the Eastern Daily Press assured readers that “no effort is being spared to imbue the spectacular symbols of the durbar with all the glowing, gorgeous colour of the Orient, and … the score … casts a powerful spell over the whole production.”16 Photographs of scenes from The Crown of India, viewed alongside the colorful illustrated reports that described the spectacle of the Delhi Durbar to the British public, show how closely the masque’s sets resembled those of the actual occasion (figure 2).17

Figure 1. “Vandalism! Or, the Partition of Bengal!” from Hindi Punch, July 1905. Courtesy the British Library.

Press reviews claimed that the masque “put the events of the Durbar in front of the British public in an attractive and concrete form” and that it was “a reconstitution of the scene of the Durbar.”18 Yet the masque staged only part of the events. The first tableau was dominated by the dispute between the cities of India as to whether Delhi or Calcutta should become the new imperial capital and the second tableau featured India and all her cities assembling with the character of St. George and the East India Company to do honor to England and the British Raj.19 That the masque represented (in great detail) transfer of the capital to Delhi is unsurprising, since the move was a calculated step to guarantee the continuance of British rule in the face of ever-increasing Indian demands for political power: Delhi had a long history as the site of India’s imperial throne.20 Yet the most significant moment of the Durbar, the reunification of Bengal, found no mention in The Crown of India, despite the king’s dramatic announcement (reportedly “making history and geography at once”), which might have seemed ideal material for the Coliseum masque.21 Bengal could not be represented because it alluded to a spectacular policy failure and also suggested the narrowing limits of imperial authority. Thus a selective view of the Delhi Durbar, achieved by ignoring successful native resistance to the Raj that led to the partition repeal, served the interests of both the Raj and British sovereignty.

Figure 2. India, from the steps of the throne, hails the advent of the King-Emperor and Queen-Empress: A scene from the Crown of India masque, Daily Graphic, 12 March 1912. Courtesy the British Library Newspapers at Colindale.

The Crown of India was, accordingly, a tool for manipulating popular consciousness.22 India’s personification in the masque, a vivid depiction of how the English spoke for India and represented Indians, determined both what could be said about India and what could count as truth. The words put into the mouth of the figure of India parrot the sentiments and ideology that the British used both to justify their reign in India and to make it palatable for themselves:

Each man reclines in peace beneath his palm,

Brahman and Buddhist, Hindu with Islam,

Into one nation welded by the West,

That in the Pax Brittanica is blest …

Oh, happy India, now at one, at last;

Not sundered each for self as in the past!

Happy the people blest with Monarch just!

Happy the Monarch whom His People trust!

And happy Britain—that above all lands

Still where she conquers counsels not commands!

See wide and wider yet her rule extend

Who of a foe defeated makes a friend,

Who spreads her Empire not to get but give

And free herself bids others free to live.23

Having the figure of India express such uncontested judgments about India and its rulers allowed Hamilton and Elgar to demonstrate to their audience that Indians accept British rule because it is “a mild and beneficent, a just and equitable, but a firm and fearless rule.”24 This has historically always been the way that European imperialism represented its enterprise, for, as Edward Said has argued, nothing could be better for imperialism’s self-image “than native subjects who express assent to the outsider’s knowledge and power, implicitly accepting European judgment on the undeveloped, backward, or degenerative nature of native society.”25 Moreover, by studiously omitting any reference to the partition repeal and excluding the all-too-present challenges to British rule, Hamilton and Elgar eliminated any chance of showing two worlds in conflict. The Crown of India, masquerading as a colorful depiction of the Delhi Durbar, was carefully inscribed with its creators’ considered beliefs and suppressions.

The Composer’s Burden

Edward Elgar had a personal connection with the ventures of the British in India. His father-in-law, Major-General Sir Henry Gee Roberts (1800–61), joined the East India Company in 1818, launching a distinguished military career. During the 1857–58 Indian Rebellion, he commanded the Rajputana Field Force that succeeded in capturing the town of Kota in March 1858.26 Later he was honored in a parliamentary motion of thanks for the skill “by which the late Insurrection has been effectively suppressed.”27 Caroline Alice, Sir Henry Roberts’s daughter, who was born in October 1848 in the residency at Bhooj in Gujarat, married Elgar in 1889, and they lived in a house scattered with Indian artifacts collected by her father.28 Following in the footsteps of his father-in-law, Elgar himself was knighted in 1904, later receiving the Order of Merit in July 1911.29

The family’s links with the Raj can be seen in the larger context of the extraordinary presence of “India” within English life during the years surrounding the turn of the century.30 Following the 1857 Rebellion, the English sought to strengthen their increasingly precarious hold on the subcontinent by perpetuating the powerful fictions (of civilizing savages, of liberal philosophy, of democratic nationalism) that justified the Raj.31 After Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India in 1876, displays of the glories of British rule in India became immensely popular. The 1886 India and Colonial Exhibition, for example, attracted nearly four million visitors.32 International exhibitions that drew attention to India were hosted by Glasgow in 1888, 1901, and 1911, and by London’s Shepherd’s Bush in 1909, 1910, 1911, 1912, and 1914.33 The 1895 Indian Empire Exhibition and the 1896 India and Ceylon Exhibition, both at Earl’s Court, together with the 1908 Franco-British Exhibition at Wembley were renowned for their displays of the arts, music, architecture, crafts, and “tribes” of India.34 These cultural practices were exhibited before the British as microcosms of the larger imperial domain.

Outside these exhibitions, representations of “India” and of the historic events of the Raj became a central subject for musical spectacles during the decades around 1900, including The Grand Moghul (1884), The Nautch Girl (The Savoy, 1891), The Cingalee (Daly’s, 1904), and H. A. Jones’s Carnac Sahib (1899). The last of these was much admired both for its jeweled palace at (the fictional) Fyzapore and for its evocative music, including excerpts from Delibes’s Lakmé and “a Hindu march.”35 Perhaps the most striking of all was the grand pageant India, produced by Imre Kiralfy, director-general of several Indian and colonial exhibitions.36 Staged at the 1895 Earl’s Court Indian Exhibition, Kiralfy’s “historical play,” with music by Angelo Venanzi, was an affirmation of English rule in India. It presented a selective account of Indian history that led naturally from the “Fall of Somnath—The Muhammadan Conquest” in 1024 to Victoria’s imperial coronation at the 1877 Delhi Durbar, culminating in a “Grand Apotheosis” in 1895 (during which “Britannia Crowns Her Majesty the Goddess of India”).37

The 1897 Diamond Jubilee celebrations had established Elgar as England’s imperial bard, a composer whose music glorified colonial policy. Elgar certainly took up “The Composer’s Burden.”38 His contribution to the Jubilee celebrations included the following works: the Imperial March (attributed to Richard Elgar!) played by vast military bands at the Crystal Palace early in 1897 and later by special command of the queen at the State Jubilee Concert (the only English work on the program); the two cantatas, The Banner of St. George, with its grand finale glorifying the Union Jack, and Caractacus, its ancient context encompassing the fall of the Roman Empire and prophesying the rise of the British nation.39 Performances of the Imperial March during that year—at the Albert and the Queen’s Halls, at a royal garden party and a state concert, and at the Three Choirs Festival—placed Elgar in the position of laureate for imperial Britain. The Crystal Palace hosted another grand occasion that year at which a new Elgar work was premiered. For this event, held in October 1897, “Ethnological Groups,” including “Indians, Bushmen, Zulu Kaffirs, Mexican Indians, Hindoos [sic], Tibetans,” were put on display in the south transept. Elgar contributed Characteristic Dances to the program.40 Five years later, Henry Wood gave the London premiere of Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance Marches in D Major and A Minor, conducting two encores of the former.41 Charles Villiers Stanford remarked that “they both came off like blazes and are uncommon fine stuff” that “translated Master Kipling into Music.”42 In October 1902, Elgar composed the Coronation Ode to commemorate the accession of Edward VII and his crowning as Emperor of India. At the king’s suggestion, the Ode included the choral setting of the expansive trio melody of Pomp and Circumstance March no. 1, a tune that would in Elgar’s words “knock ‘em flat” and which became known across the world (with words by A. C. Benson) as “Land of Hope and Glory,” the anthem of British imperialism.43

Yet, as inferred from the policies announced at the Delhi Durbar, these imperial festivals, resounding with marches and hymns, marked a high point for the public face, but not the imperial power, of British rule in India. An apologist for the Raj, Tarak Nath Biswas, prefaced his 1912 study of the Durbar by emphasizing how far relations had deteriorated within the Anglo-Indian colonial encounter:

The present peculiar situation of India demands a popular exposition of the bright side of the British rule, for the shade of discontent that one unfortunately notices in the country, can only be removed by a better understanding of our rulers and their beneficent and wellmeaning administration.44

The “shade of discontent” is an oblique reference to the seven years of horrors unleashed by the Bengal partition, and the “bright side of British rule” masks the fact that radical Bengali nationalists and other “enemies of empire” were sent to a prison of death on the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal.45 While The Crown of India boasted of Britain’s “beneficent and well-meaning administration” to a packed Coliseum during March 1912, English officials were hanging Indian dissidents in a desperate attempt to avoid a full-scale mutiny. As with so many of Elgar’s imperialist works, The Crown of India, in its subject matter, march topoi, brassy scoring, and massive performing forces, was secretly addressing a crisis of imperial—and thus national—self-assurance.

“East Is East and West Is West.”

Remarks by Elgar during the masque’s composition indicate the composer’s enthusiasm for the project. His earliest thoughts about the masque, outlined to Alfred Littleton of Novello, his publisher, on January 8, 1912, describe it as “very gorgeous and patriotic.”46 By February 3, the Daily Telegraph reported that Elgar had “expressed the keenest satisfaction with Mr. Hamilton’s work.”47 Later that month the composer declined an invitation from friends, explaining, “I must finish the Masque—which interests and amuses me very much.”48 Elgar divided Hamilton’s elaborate reconstruction of the Delhi Durbar into two tableaux comprising some twenty musical numbers together with passages of mélodrame.49 The cast was headed by “India” (played by Nancy Price), with twelve of her most important cities, Delhi, Agra, Calcutta (now Kolkata), and Benares (now Varanasi), as female singing roles; in addition, the masque featured St. George, Mughal emperors, the King-Emperor and Queen-Empress, and a herald called Lotus.

At rehearsals Elgar told the press he found the work hard but “absorbing, interesting.”50 The composer himself conducted the masque twice a day for the first two weeks of its successful run, often running rehearsals between performances.51 His dedication paid off, not least financially: “God Bless the Music Halls!” he exclaimed to a friend, Frances Colvin, at the thought of his emolument.52 The masque—and particularly its “gorgeous and patriotic” music—proved enormously popular with audiences and critics alike. In the production’s fourth week it was still, the Daily Telegraph reported, “a case of ‘standing room only’ at the Coliseum soon after the doors were opened for both the afternoon and evening performances.”53 England’s popular tabloid, the Daily Express, trumpeted Elgar’s “great triumph at the Coliseum,” declaring that “the call was for Elgar at the fall of the curtain… . Truly, The Masque of India is the production of the year.”54

The success of Elgar’s music was due at least in part to the manner in which the score drew on representations of India and its music that were then all the rage in popular culture. The London Times told readers that “the score contains ideas drawn from Oriental sources,” pointing to inclusion of the most un-Indian of instruments, “a new gong” contrived by Elgar “for his special purpose.”55 A “native musician with tom-tom” and a pair of “snake-charmers with pipes” also figured in the opening scene, the former by way of the tenor drum, and the latter by oboes. These touches suggest that Elgar must have absorbed the manner in which Indian music was routinely represented at exhibitions, to wit by “snake-charmers … dancers, musicians, jugglers, and beautiful Nautch girls.”56 Nothing in The Crown of India would have been recognizable as Indian music to an Indian musician, but for audiences caught up in the celebrations of the Delhi Durbar, and with exhibition entertainments ringing in their ears, these allusions were more than sufficient to establish the proper atmosphere. The Crown of India’s libretto, together with the elaborate costumes and stage design of its Coliseum run, brought it close to the late-nineteenthcentury “Indian” stage spectacle in which bayadères and Mughal emperors appeared in London’s music halls and theaters. Moreover, similar in theme, representational style, and imperial purpose to Kiralfy’s India, The Crown of India was intended as an edifying, historically accurate entertainment.

After completing the score, Elgar explained that “the subject of the Masque is appropriate to this special period in English history, and I have endeavored to make the music illustrate and illuminate the subject.”57 A perceptive review in The Referee addressed the difficulties of representing the Durbar musically:

When Sir Edward Elgar undertook to write music for a masque dealing with historical events in India for the Coliseum he was faced by several problems not easy to solve harmoniously. It was essential that the patriotic note should be made prominent. It was also distinctly necessary to suggest the mystery of the East… . Sir Edward might have made use of the Indian scales … and, by contrasting the two systems of music, reflected in his score the difference of Indian and British outlook. Mr. Hamilton’s libretto, however, mainly regards India from a British standpoint… . The result is that while his music illustrating the Indian portion of the libretto appeals to musicians who will distinguish with pleasure the hand of a master in subtleties of tone-colour and cross rhythms, the chief effect on the ordinary listener is almost entirely confined to the song, “The Rule of England.” This, with its diatonic refrain, sounds the imperial note of popular patriotism.58

Audiences did indeed delight in St. George’s song: critics described it as “a patriotic song of honest ring,” “very stirring,” and “destined to be heard for many a day outside the Coliseum walls.”59

The appeal of St. George’s rousing solo “Rule of England” can be understood in the context of its popular musical language, for which Elgar drew on several well-known idioms of the day. The chorus’s energetic four-square melody and marching bass, along with the text’s call to arms and imperialist sentiments, is akin to the “crusader” hymn tradition in general and to the popular exemplar “Lift High the Cross” in particular. The militaristic idiom and lofty imperialism expressed in such hymns and patriotic songs had been caricatured in Gilbert and Sullivan’s operettas to great acclaim at the Savoy Theatre since the 1870s.60 Elgar owned several of these libretti and had seen, played in, and conducted many of Sullivan’s works in the 1880s and ’90s, including Iolanthe which, along with HMS Pinafore, seems to have inspired “Rule of England.”61 Ironically, or perhaps with original irony intact and intended, echoes of Sullivan’s imperialist spoof, “He is an Englishman” (HMS Pinafore) can be heard in the male chorus section of St. George’s song with its marching bass and nationalistic text. And “Rule of England’s” risoluto section, with its ostinato, marked marcato, and lofty sentiments, appears to have strayed out of Lord Mountararat’s song with chorus: “When Britain really ruled the waves … in good King George’s glorious days.” Elgar even invoked his own “Land of Hope and Glory” in the song’s accompaniment to tug at nationalistic heartstrings.62

In contrast to this popular patriotism, the “Dance of the Nautch Girls” is one of the pieces “illustrating the Indian portion of the libretto” that “appeals to musicians who will distinguish with pleasure the hand of a master in subtleties of tone-colour and cross rhythms.” In writing a nautch girl’s dance, Elgar was tapping in to one of the most pervasive cultural signifiers of India in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century England. From the early days of the Raj, Indian dance had been a popular form of entertainment for the English. Yet, familiar with such dances as the waltz, the colonizers tended to misunderstand the dance they came across most often: kathak, the north Indian performance genre that includes mime, singing, accompanying music (usually tabla and sarangi) and intricate rhythmic improvisations with the feet in response to virtuosic tabla sequences.63 Kathak has a strong erotic character, as it often depicts the amorous exploits of Krishna with his consort Radha. Although traditional kathak dates back to the progressive Bhakti movement of medieval times and was later danced by skilled courtesans, or tawaifs, at the royal courts, it had, by the turn of the twentieth century, become synonymous with what foreigners termed “nautch” dancing (from the Hindi nach, meaning dance), a derogatory term associated with prostitution.64

Nautch songs and dances in all kinds of instrumental and vocal guises had become all the rage in England; these included Venanzi’s “Dance of the Bayaderes” in Kiralfy’s India, Walter Henry Lonsdale’s “Nautch Dance” for piano (1896), Frederic H. Cowen’s “The Nautch Girl’s Song” (1898), a setting of words by the well-known authority on Indian literature, Sir Edwin Arnold.65 In June 1891, the London populace first became privy to the secrets of the nautch girl when Edward Solomon’s opera The Nautch Girl began a successful run at the Savoy in a production designed, like The Crown of India, by Percy Anderson. As Hollee Beebee, a character in the opera, explained in tantalizing detail:

First you take a shapely maiden …

Eyes with hidden mischief laden, Limbs that move with lissom grace,

Then you robe this charming creature, so her beauty to enhance:

Thus attired you may teach her all the movements of dance …

Shape the toe, point it so, hang the head, arms out spread

Give the wrist graceful twist, eyes half closed now you’re posed …

Slowly twirling, creeping, curling … gently stooping, sweeping, drooping

Slyly counting one, two, three …

Bye and bye this shapely creature will have learned the nautch girl’s art,

And her eyes … throwing artful, furtive glances …

Wringing heartstrings as she dances, making conquests all along.66

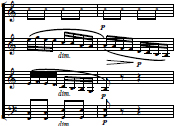

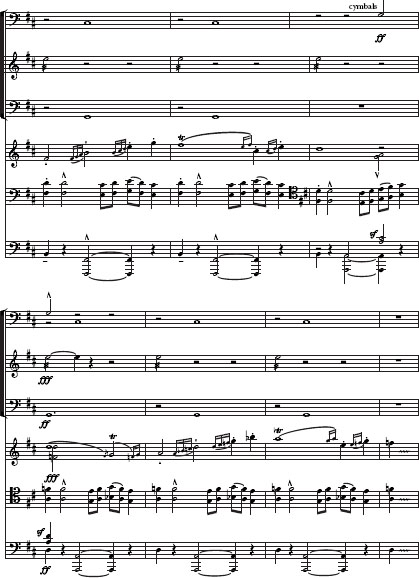

In his “Dance of the Nautch Girls,” Elgar evoked the (imagined) intricacies of kathak dance in an almost pointillistic sequence of musical gestures suggestive—to his Coliseum audience, at least—of the perceived eroticism of the dancing girl’s hand, head, and eye movements (“Limbs that move with lissom grace”/“Slowly twirling, creeping, curling”/“Eyes with hidden mischief laden”): pianissimo muted violin and flute running thirds in triplets and sextuplets with scrupulous attention to articulation; trills; tempo changes; muted string chords; and touches of muted horn, harp, and bass drum. Later, the Allegro molto features a repetitive rhythmic pattern on Elgar’s Indian drum (“Tomtoms”), along with fortissimo parallel fifths, flat leading tones, and a swirling sixteenth-note figure in flutes and piccolo to evoke the perceived wild or barbarous nature of the nautch as described by one onlooker in the late 1870s: “She wriggled her sides with all the grace of a Punjaub [sic] bear, and uttering shrill cries which resemble nothing but the death-shriek of a wild cat.” (See Example 1).67

Following the London premiere of the Crown of India Suite, one critic described the effect of hearing the “Menuetto” after the “Dance of the Nautch Girls”:

This movement follows as if to illustrate the statement that “East is East and West is West” in the dance as in other matters. Nothing could be in more effective contrast to the tempestuous conclusion of the Nautch Dance than this quiet and majestic old-world Minuet.68

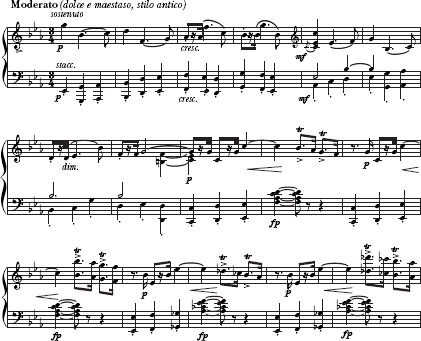

Beyond the irony that the minuet could be considered “old world” in comparison with the centuries-old tradition of kathak, the critic’s reference to Kipling’s “Ballad of East and West” (“Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet”) lends perspective to our understanding of The Crown of India’s music.69 In the masque, the stately E-flat minuet, titled “Entrance of John Company,” heralded the highest officials of “the Honourable East India Company” including Clive of India, Lord Wellesley and Warren Hastings, as well as several “heroes” of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 such as Sirs Henry Lawrence, Colin Campbell, and Henry Havelock. Marked dolce e maestoso, stilo antico, its trills and rhythmic gestures conjure up the social hierarchy of courtly eighteenth-Century European aristocracy in which the minuet promoted a particular kind of grace, agility, and control (Example 2). The minuet exemplified the European idea of dancing as a social activity in which both sexes participated. It would be difficult, then, to find two more contrasting dance forms and musical accompaniments than the European and Indian styles that Elgar depicted in his masque.

Example 1. Allegro molto, “Dance of the Nautch Girls,” Crown of India

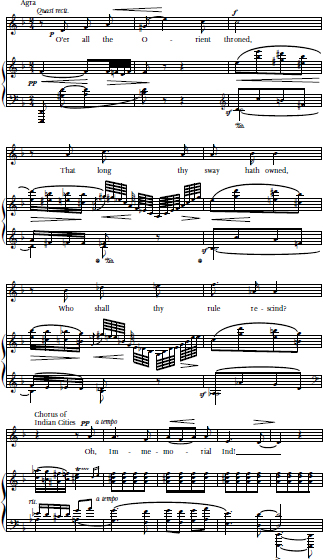

Perhaps Elgar’s most exotic composition in the masque, and indeed in his entire output, is Agra’s “Hail, Immemorial Ind!” Yet, far from displaying the kind of studied musical orientalism of the “Dance of the Nautch Girls,” Agra’s song has a refined musical setting in which Elgar drew on elements of his personal idiom and, inspired by the Indian subject, expanded their expressive capacities.70 The name Agra was evocative both for Elgar and his audience: it was the former capital of the Mughal Empire and the location of several wonders of the Muslim world, including Emperor Akbar’s city Fatehpur Sikri and Shah Jehan’s Taj Mahal, which served as Agra’s backdrop at the Coliseum.71 The song unfolds in the form of a historical “mythography” of India’s glories from ancient times to British conquest and rule and is, as Benares explains, essentially an homage to India:

O Mother! Maharanee! Mighty One! …

Thy daughters bless thee and their voices blend

With that unceasing song.72

Written for alto solo and an orchestra scored to depict the mysterious delights of the distant land of its text, Agra’s song recalls Elgar’s earlier song cycle for alto and orchestra, the well-known Sea Pictures (1897–99). The sea—Shakespeare’s realm of “strange sounds and sweet aires”—inspired a highly evocative, often exotic musical language for Elgar (as it did for other composers, including Debussy, Ravel, and later, Britten). While Elgar seems to have used these earlier songs as a touchstone for Agra’s aria, the Indian imagery of Hamilton’s verse evidently suggested to Elgar an extended and more nuanced vocabulary of musical expression with which he evokes every detail of this historical paean to India.73 Agra’s rich contralto, timbrally redolent (for an audience brought up on nineteenth-Century exotica) of the feminized East, begins with a refrain colored by an insistent and exotic augmented triad (A–C#–F), and closes with a suspended ninth resolving downward in the lowest regions of the orchestra (bass tuba, basses, bass drum). This gesture is derived from Agra’s singing of “Ind” and it musically suggests the ancient, mystical, and, in Agra’s own description, “dark” depths of “immemorial” India (see the first return of this refrain as it is taken up by the chorus of Indian cities in Example 3). Agra’s “quasi recitative” is peppered with tritones that call to mind “the Orient,” as Elgar’s setting of those words to a rising G#–D attests. Her vivid descriptions are brought to life by an attendant orchestra of shimmering ponticello tremolo strings, harp, flute, oboe, bassoon, clarinet, piccolo, cymbals, triangle, and glockenspiel that lead Agra’s narrative through a harmonic sequence of chromatic lines punctuated by diminished-seventh harp glissandi and ornaments (see fourth bar of Example 3).

Example 2. Moderato, “Menuetto,” Crown of India.

Example 3. Agra’s aria, “Hail, Immemorial Ind!” Crown of India

Agra’s aria, along with the rest of the masque, has largely been condemned to the obscurity its colonialist premise might seem to deserve.74 The complete music from the masque was published in vocal score by Enoch & Sons in 1912, but only the well-known orchestral suite, originally published separately by Hawkes & Son (owing to the demise of the Enoch firm in the 1920s), is extant in full score and parts.75 When, in 1975, Leslie Head wished to conduct the complete masque, only two movements could be found (Agra’s song and the “Crown of India March”), and any performance of the work today would involve orchestrating the vocal score. How far, though, do memories of the masque inform our hearing of the Crown of India we know today, the orchestral suite, op. 66?

Can the Mughals March?

Martial music, in a decidedly Indian vein.

—The Daily Sketch, 12 March 1912

In September 1912, six months after the successful run of his imperial masque, Elgar conducted the premiere of his Crown of India Suite, comprising five movements: Introduction, Dance of the Nautch Girls, Menuetto, Warriors’ Dance, Intermezzo, and March of the Mogul Emperors.76 Praised as one of Elgar’s exemplary marches, this last was favored by its composer, who chose to record it several times, the last being with the Gramophone Company in 1930.77 These recordings were made, along with “Dance of the Nautch Girls,” to the delight and approval of Elgar who declared “Mogul Emperors” to be “a terrific! record.”78 The following year, Alan Webb recalled his first meeting with Elgar: “It at once became evident that most of the evening would be taken up with listening to records… . I was fascinated by his choice … of his own music, we had ‘March of the Mogul Emperors’ from The Crown of India, the new Pomp and Circumstance March no. 5, and the opening and close of the First Symphony.”79

Soon after the Crown of India’s run at the Coliseum, the “March of the Mogul Emperors” was singled out as a popular choice for patriotic and imperial occasions. A fine example of the former is the “great patriotic concert” held at the Royal Albert Hall in April 1915 which involved more than four hundred performers drawn from army recruiting bands, and from which all proceeds went to the Professional Classes War Relief Council and the Lord Mayor’s Recruiting Bands.80 At the concert, “Mogul Emperors” was featured alongside “Land of Hope and Glory” and such favorites as “Tipperary” and “Your King and Country Need You.” Nearly a decade later, Elgar contributed music for the British Empire Exhibition held at Wembley in the summer of 1924.81 His name appeared some twenty times on the program of the grand Pageant of Empire, most prominently in “The Early Days of India” that featured his Indian Dawn (setting of Alfred Noyes) written for the occasion, along with three numbers from The Crown of India: the Introduction, the “Crown of India March,” and the “March of the Mogul Emperors.”82 These, interspersed with the other exemplary “Indian” works such as Old Indian Dances by an unidentified Shankar (undoubtedly Uday), represent what best depicted India for the British public and how India was perceived.83 For an England intoxicated by imperial power, India could be no more vividly evoked than by Elgar’s “Indian” March.

In a preview of the masque, a critic for the Daily Telegraph had noted that “the score fairly bristles with marches, in the composition of which we all know Elgar to be an expert.”84 Some seventy years later Michael Kennedy exclaimed that the “clue” to Elgar’s marches is “how nostalgic they are,” and that “they also represent aspiration and hope”; he described the “March of the Mogul Emperors” in particular as “a fine piece of Elgarian imperialism which requires no apology.”85 More recently, in her article on the composer for the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Diana McVeagh suggests:

[Elgar’s] unaffected love of English ceremonial, and of the grand moments in Meyerbeer and Verdi, prompted him to compose marches all his life: independent pieces like [the Pomp and Circumstance marches], or for particular occasions (Imperial March, 1897; Coronation March, 1911; Empire March, 1924) or as parts of larger works (Caractacus, The Crown of India). Mostly they are magnificent display pieces, apt for their time, and still of worth, if they can be listened to without nostalgia or guilt for an imperial past … Elgar’s march style causes embarrassment only where it sits uneasily, as in the finales of some early choral works, or as an occasional bluster in symphonic contexts.86

We might, however, also understand Elgar’s celebrated marches, especially “Mogul Emperors,” as belonging, musically and ideologically, to the late-nineteenth-Century tradition of the march as the favorite signifier of the Raj. By midcentury, the prevailing militarism was generating marches with titles such as “Empire,” “Oriental,” “Battle,” “Hindu,” “Cavalry,” “Delhi,” and even an “Indian Wedding March.”87 In Adolphe Schubart’s fantasia The Battle of Sobraon, published in London in 1846, Sikhs can be heard marching to their entrenchments to the strains of “There Is a Happy Land.”88 Queen Victoria’s crowning as Empress of India in 1876 inspired a further plethora of the genre, including John Pridham’s The Prince of Wales’ Indian March (1876) and General Roberts’ Indian March (1879), whose title refers to Elgar’s father-in-law.89 Kiralfy’s India featured two “grand” marches, those of “the Rajahs at Delhi” and of “the Mogul Court.” By the 1897 Diamond Jubilee, the march had come to signify both imperial expansion and national celebration; in the process, it had become linked specifically with British India, as exemplified by Thomas Boatwright’s 1898 Indian March: The Diamond Jubilee.90

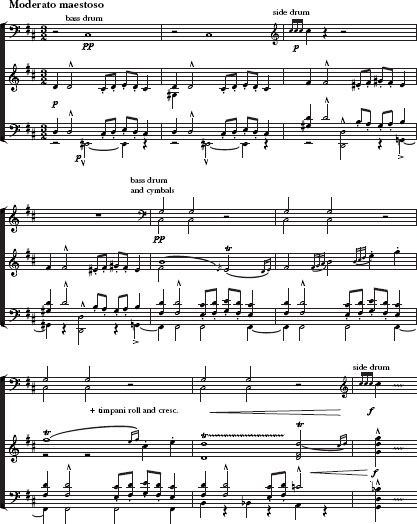

The “Mogul Emperors” was not Elgar’s first exotic march. It followed by eleven years Pomp and Circumstance March no. 2, dedicated to the master of Indo-Persian exotica, Granville Bantock. In that earlier (nonprogrammatic) A minor march, Elgar created an exotic sound chiefly by omitting the leading tone in the main theme. For these marching Mughals, Elgar expanded his orientalist musical armor considerably. At first glance the stately moderato maestoso with its marziale and pomposo sections played by a vast orchestra of full brass and percussion (cymbals, timpani, bass drum, side drum, tambourine, tom-tom, and large “Indian” gong) does seem to be an unequivocal instance of Elgarian imperialism. Listening to the music with insight, however, suggests a rather different interpretation. The first sounds we hear hint at the march’s unconventional character; the piece begins not, as we have come to expect from such a genre, with consonant affirming triads but with an accented diminished seventh (EJ-D) followed by a dissonant tritone (D-GJ /GJ -D) as if to conjure up the oriental despotism of the Mughal emperors depicted within (Example 4).91

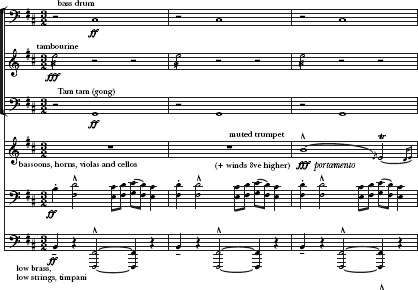

In The Crown of India masque, this was the music that accompanied the emperors Akbar, Jehangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb onto the Coliseum stage: “Four names,” Delhi announces, “whose splendours nothing shall annul … Come, oh ye mighty ones from out the Past”92 Unusually for Elgar’s marches, the music is cast in 3/2 with a distinctly triple-meter feel, lest we forget Kipling’s rejoinder that it was, after all, “well for the world” only if the “White Men tread their highway side by side,” marching in 2/4 or 4/4 naturally!93 Indeed, Elgar’s Mughals do not march at all, but rather “process” to a (thinly disguised) polonaise, with all its ceremonial associations, just as Rimsky-Korsakov’s Nobles did in Mlada (1892).94 Elgar’s three swaggering beats divided by two; second-beat accents (see Example 4); striking eighth-note fanfare figures; and the appearance of the rhythm popularized in examples of this genre by Chopin, Glinka, Tchaikovsky, and others, reveal this “march” to be a polonaise. (Example 5, a rare passage of thematic development, shows the polonaise rhythm that permeates the final section.) For these courtly Mughals of bygone times, Elgar drew on the polonaise’s history in nineteenth-Century Russian art music as a stately, processional dance associated with the court; in this guise the polonaise often replaced the march where official “pomp and circumstance” was desired.95 While the “Mogul March” emulates the particular style of Rimsky-Korsakov’s grand maestoso polonaise with its brassy fanfares and prominent timpani, Elgar may also have known the “parade-ceremonial” polonaises with patriotic overtones in Tchaikovsky’s Vakula the Smith and Yevgeny Onegin, and in the opening choral pageant of Borodin’s Prince Igor.96

Example 4. Opening, “March of the Mogul Emperors,” Crown of India.

Example 5. Polonaise, “March of the Mogul Emperors,” Crown of India.

The generic resonance of the polonaise with which Elgar tacitly casts his Mughal music effectively invokes not only noble or martial associations but also, more significantly, the borderline between dance and processional. Elgar thereby suggests, with the help of several orchestral effects designed specifically for his Mughal depiction, the image of a colorful, festive oriental parade. As the motif introduced in bars 5–8 (see Example 4) is extended upward in a series of trills and pseudo-glissandi, it seems to mimic the trumpeting of elephants as they carry their Mughal masters. This is particularly striking when trumpets, muted (for effect rather than volume), repeat the phrase portamento (with slides) and fortississimo; they are punctuated by bass tuba, trombones, bass clarinet, contra-bassoon, double-bass, timpani, bass drum, and “Indian” gong (tam-tam) in second-beat accents (a la polonaise) suggestive of ponderous elephant steps (Example 6). These trumpet trills, used earlier in the masque’s minuet to portray European gentry in the entrance of the East India Company, now gaudily cloaked by tambourine, cymbals, and gong, become audible manifestations of Indian ornamentalism (opulent Mughal costumes and jewelry, lavishly decorated elephants, bejeweled Mughal swords, and so on). A series of illustrations of “Greater Britain” published in The Sketch, a popular London weekly, demonstrates how the Mughal emperors and elephants Elgar depicted in the march served, at the time, as symbols of India itself (figure 3).97 India, for the British, in Elgar’s march as in The Sketch’s illustration, is represented as a bejeweled, hedonistic, and trumpeting elephant-Emperor, an allegory of wealth and self-indulgence.98

Example 6. “Trumpeting” motif, “March of the Mogul Emperors,” Crown of India.

Figure 3. “India.” Part of “Greater Britain.” The Sketch, 21 April 1897. Courtesy the Bancroft Library collections, University of California at Berkeley.

Elgar’s marches, like most examples of the genre (and famously on account of Pomp and Circumstance March no. 1), contain a central trio section of a less martial, more lyrical or nobilmente character. Yet the Mughal emperors’ polonaise has no such trio to interrupt the fanciful orientalist procession. Instead, the “trumpeting” motif dominates, taken up by all the instruments in turn and juxtaposed with the dissonant opening theme. This trumpeting, together with the militaristic polonaise rhythm reiterated by timpani and side drum, and the heavy second-beat polonaise-style elephant steps punctuated by cymbals and bass drum conjure what the Musical Times referred to as “the magnificent barbaric turmoil” of this inspired, and somewhat eccentric, polonaise.99

Elgar the Barbarian

The cymbal-crashing, gong-ringing fortississimo that brought to a close the “Mogul March,” and hence The Crown of India Suite, came to embody the acme of Elgarian imperialism for the musical intelligentsia after the First World War. In A Survey of Contemporary Music in 1924, Cecil Gray, Scottish critic and composer, established what was to become a trope (with minor alterations) in Elgar criticism: the distinction between “the composer of the symphonies and the self-appointed Musician Laureate of the British Empire.”100 Concluding that “the one is a musician of merit; the other is only a barbarian,” Gray denounced all of Elgar’s marches, odes, and other occasional pieces, particularly The Crown of India—which he found “undoubtedly the worst of the lot”—as “perfect specimens” of jingoisim. By 1931, The Crown of India was, for F. H. Shera, professor of music at the University of Sheffield, an almost unmentionable piece of Elgar’s imperialism that had been “allowed to fade into deserved oblivion.”101

While Gray’s and Shera’s criticisms reveal the contemporary attitudes of many critics and modernists of their generation, they tell us little about the continuing popularity of Elgar’s music with the British public. In his study, “Elgar and the BBC,” Ronald Taylor states that by 1922, Elgar’s music could be heard on at least one of the BBC stations most days of the year.102 Significantly, not only were his imperial works among the most regularly broadcast but, of them (apart from the literally countless broadcasts of “Land of Hope and Glory” and Pomp and Circumstance March no. 1), The Crown of India suite (the “worst” product of Elgar’s “barbarian” mind) was heard most frequently—102 times between 1922 and 1934.103

Radio Times, a magazine reflective of popular tastes, featured an article in December 1932 that appears to have been crafted in response to the criticisms of Gray, Shera, and others. The author, Alex Cohen, in a spirit of fervent support for the Raj, suggested that “superior folk” had “sniffed” at Elgar’s imperialism and that these detractors thought the composer “should have adequately equipped himself … first by a study of oriental mysticism … followed by a few years apprenticeship as a Hindu ascetic.”104 Cohen’s contempt for such criticism of Elgar’s lack of engagement with India in his music is evident in his retort, in which he derided not only the Indian practice of meditation but also Mohandas K. Gandhi’s satyagraha in particular as years of Hindu asceticism Elgar “might have spent standing on one leg and contemplating the very essence of things until he grew talons a yard long and could subsist on air alone.” (Gandhi’s staunch adherence to satyagraha was widely considered by many British at best eccentric and at worst an extremely effective form of resistance.) Cohen concluded that “west is not east and the miracle has never been achieved … he was the child of his environment” who, accordingly, had mixed in his music “the faith of St Francis the Visionary and an admiration for Cecil Rhodes, the Empire-builder.”105

Along with the position accorded The Crown of India by Gray, Shera, and others in their censure of Elgar’s imperialist music, Cohen’s perceived connection between Elgar’s orientalism and the maintenance of colonial rule in India suggests a way of understanding the critics’ changing interpretations. Their rejection of The Crown of India and other imperialist works in the late 1920s and early 1930s coincides with significant changes in Anglo-Indian colonial relations and policies during that time. In 1930, Gandhi broke the salt law, thereby setting in motion a flurry of civil actions against British authorities; that year also saw the first roundtable conference summoned by the British concerning a new Indian constitution. Anticolonial sentiments from English liberals intensified in the face of negligible native participation in the constitution’s makings and even more in 1932 when the Indian Congress was declared illegal and Gandhi was arrested. It was perhaps neither Elgar’s death in 1934 nor a received view that his music had become outmoded but rather the passing of the Government of India Act in 1935 that proved the most potent catalyst for his music’s reinterpretation as pastoral. The India Act provided for the establishment of an All-Indian Federation and a new system of government on the basis of provincial autonomy—signaling the beginning of the end of colonialism. As Jeremy Crump argues:

Only in the 1930s, at the time of the Peace Pledge Union and concern for the League of Nations, when the Indian Act [of] 1935 marked a commitment to a less expansionist phase of colonial imperialism, [did] the pastoral became dominant in some interpretations of Elgar. The retreat to rural values was consonant with the view of “sunset splendour” in the Edwardian Elgar, and coincided with a cultural conservatism, marked in music by the decline in the fashion for experimental works like Walton’s Fagade (1921).106

Thus, the earlier association of empire and the war was dismissed from Elgar’s music so that it could provide a locus of nostalgia for the Edwardian era. Along with the ever-growing resistance to English imperial might in India, the breakup of landed estates and economic crisis all contributed to what Crump describes as “a yearning for past glories and a mythical, stable social order”—at home and in the colonies.107 In response to this yearning, Elgar’s music was reinterpreted as redolent of the imagined virtues of a preindustrial rural Britain that many sought. His music was not only increasingly related to the English countryside but was also seen as belonging to the folk music revival, particularly by Ralph Vaughan Williams, who suggested that Elgar’s exploitation of the musical idiom of “the people” was comparable with Burns’s and Shakespeare’s use of the vernacular.108 Writers at this time often emphasized the English spirit of Elgar’s music, asserting its power to “express the very soul of our race,” as Ernest Newman put it in 1934, much as during previous decades.109

One of the strategies used to distance this intangibly English Elgar from the English imperial enterprise is to largely ignore his nationalistic works (except at graduation time or the Last Night of the Proms). Lovers of Elgar’s music have, since the 1930s, regularly tried to save the composer from himself. As a result, the established Elgar canon is based on the Enigma Variations, the symphonies and concertos, the overtures, Dream of Gerontius, and some smaller instrumental works, including the Serenade, and Introduction and Allegro for strings. The subsequent dismissal of a large body of Elgar’s music has been justified by denying the integrity of his output and appealing to the “two Elgars” theory, seen in embryo in Gray’s criticism.110 In 1932, A. J. Sheldon claimed that “political ideas can never inspire the artist in the same way, or to a like extent, as poetical ideas can.” Thus he declared that Elgar’s music connected with imperialism “should be buried soon; at present it is a clog on the endearing place Elgar holds in our estimation.”111 Three years later, Frank Howes clarified this view of the two Elgars, with only one worthy of retaining, stating that “the two Elgars may be roughly described as the Elgar who writes for strings and the Elgar who writes for brass.”112

The result has been that long-established nationalistic myths (pastoral, spiritual, and nostalgic) have dominated interpretations, forming the basis of the composer’s revival in the 1960s.113 Historian Jeffrey Richards has noted that the pillars of this revival, Ken Russell’s BBC documentary Elgar (1962) and Michael Kennedy’s Portrait of Elgar (1968), “seriously distort the picture” because of a desire to “exculpate Elgar from imperialism.”114 Works like The Crown of India have thus either been put off limits or uncritically celebrated. Yet, listening insightfully to Elgar’s music with attention to its political subtext can tell us far more about the music and its times than abstract notions of imperialism.

The emergence of a postcolonial consciousness has sparked discussion about the British Empire that promotes a new understanding of what Britain was—and is. Landmark scholarship has done much to remedy the historiographical distortions surrounding the composer and his music.115 Alain Frogley recently argued that consideration of imperialism by scholars of English music is a necessary part of challenging “the prevailing orthodoxies of British music historiography.”116 Thus, while a reevaluation of Elgar is well under way, one of the challenges for historians of early-twentieth-century England today is to connect the musical works of Elgar and his contemporaries not only with the pleasure of listening but also with the British imperial enterprise—particularly the Raj, “a reign of such immense range and wealth as to have become a fact of nature for members of the imperial culture.”117

In this context, Elgar’s Crown of India, like Rudyard Kipling’s Kim (1901), can be understood to be central to the high point of the Raj and in some ways to represent it. The masque is a fascinating work of imperialism: historically illuminating and often musically rich, it is nevertheless a profoundly embarrassing piece—a significant contribution to the orientalized India of the English imagination.118 We might hear it, in some ways, as the realization of British imperialism’s cumulative process: the control and subjugation of India combined with a sustained fascination for all of its intricacies. As The Crown of India’s emphases and omissions suggest, Elgar not only recognized the nature of imperialism, but also recognized the situation of the Empire in the early years of twentieth century, when it began to dawn on the British that India was once independent, that England now dominated it, and that, in time, growing native resistance to British rule would inevitably win back India’s freedom.119

But there is, I think, a larger conclusion. The works of the “real” Elgar have, for the most part, been received as powerful artistic statements from the pioneer of English musical nationalism. Yet the critical obsession with identifying in them an essential Englishness, while ostensibly intended as an affirmation of their worth, has served only to separate the music from the mainstream and confine it within the nation’s boundaries. That Elgar has often been drawn on to define England musically has set the limits on what should—and can—be heard in his music. Reluctance to acknowledge that Elgar’s music is imbued with traces of the empire it played a part in promoting is reflective of a larger and equally counterproductive unwillingness to understand modern England as having been, in many ways, shaped by its colonial rule and its colonial Others.

NOTES

I am indebted to Richard Taruskin who helped me at every stage in my examination of Elgar’s musical relation to the British Empire. Thanks also to Roger Parker and Bonnie C. Wade for their enormously helpful critical input on an earlier version of this chapter. I am also grateful to Mariane C. Ferme, Paul Singh Ghuman, and the late Edward W. Said for their role in shaping my work on imperialism and music. Thanks also to Byron Adams, Alain Frogley, Mary Ann Smart, and Paul Flight for their suggestions, advice, and encouragement at various stages of my work. Finally, I appreciate the assistance offered to me by staff at the Elgar Birthplace Museum during my research visits there.

1. The Pall Mall Gazette from which this essay’s epigraph was drawn was found in the cuttings files, Elgar Birthplace Museum, Lower Broadheath, Worcester, vol. 7 (June 1911–June 1914), ref. 1332, 9; hereafter, EBM Cuttings.

2. A “Kinemacolour” film of the Delhi Durbar, titled With Our King and Queen Through India, was shown in London from February 1912. E. A. Philp, With the King to India, 1911–12 (Plymouth: Western Morning News Co., 1912); The Historical Record of the Imperial Visit to India, 1911, compiled from the official records, with illustrations (London: John Murray, 1914). The “Programme of Ceremonies” is included in The Delhi Durbar Medal 1911 to the British Army, ed. Peter Duckers (Shrewsbury: Squirrel Publishing, 1998); John Fortescue, Narrative of the Visit to India of Their Majesties King George V and Queen Mary and of the Coronation Durbar Held at Delhi 12 December 1911 (London: Macmillan, 1912).

3. N. D. Barton, “The Durbar Ceremonials,” in At the Delhi Durbar 1911: Being the Impressions of the Head Master and a Party of Fourteen Boys of the King’s School, Parramatta, New South Wales, Who Had the Good Fortune to be Present (March 1912), ed. Stacy Waddy, British Library, India Office: ORW 1989, A.2237, 22–28.

4. Ibid., 71.

5. Gargi Bhattacharyya has observed that the dutiful use of the term British rather than English glosses over the fact that in power relations there is no difference between them: British was imposed by the English on the non-English. For this reason, I generally use these terms interchangeably. “Cultural Education in Britain,” from the Newbolt Report to the National Curriculum, in Robert Young, ed., “Neocolonialism,” Oxford Literary Review 13 (1991): 4–19, 19n.

6. Quoted in Shelland Bradley, An American Girl at the Durbar (London: John Lane, 1912), 162–63.

7. The boundaries of the old province of Bengal, those of the provinces in 1905, and the provinces as rearranged in 1911 are shown in Muir’s Historical Atlas—Mediaeval and Modern, 9th ed., ed. R. F. Treharne and Harold Fullard (London: George Philip and Son Ltd., 1962), 73.

8. For a detailed account of these years, see Nirad Chaudhuri, “Enter Nationalism,” The Autobiography of an Unknown Indian (1952); repr. in Modern India: An Interpretive Anthology, ed. Thomas Metcalf (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Private Ltd., 1994), 303–22.

9. Barjorjee Nowrosjee, ed., Cartoons from the “Hindi Punch” 1905 (Bombay: Bombay Samachar Press, 1905), 57.

10. Richard Paul Cronin, British Policy and Administration in Bengal, 1905–1912: Partition and the New Province of Eastern Bengal and Assam (Calcutta: Firma KLM Private Ltd., 1977), 207–13.

11. Ibid., 441.

12. Ibid., introduction, in which Cronin analyzes the implications of the partition and its repeal.

13. The London Coliseum program for the opening week of the masque (commencing March 11, 1912) is in the British Library (BL): London Playbills (1908–13), ref. 74/436. Two copies are also held at the Elgar Birthplace Museum: Concert Programmes (Jan–July 1912), ref. no. 1126.

14. Times, 9 January 1912, 6.

15. Daily Telegraph, 4 March 1912, EBM Cuttings, 16.

16. Eastern Daily Press, 24 February 1912, EBM Cuttings, 16.

17. Three photographs from the masque appeared in The Daily Sketch,12 March 1912, 8–9. Illustrations and photographs of the Delhi Durbar abound: see, for instance, John Peeps Finnemore, Delhi and the Durbar with Twelve Full-page Illustrations in Colour by Mortimer Menpes (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1912); Sir Stanley Reed, KBE, The King and Queen in India. A Record of the Visit of Their Imperial Majesties to India, from December 2nd 1911 to January 10th 1912 (Bombay: Bennet, Coleman & Co., 1912); The Great Delhi Durbar of 1911, written to accompany a series of lantern slides (1912), BL: 010056.g.26.

18. The Standard, 1 March 1912, EBM Cuttings, 16.

19. The Crown of India: An Imperial Masque, written by Henry Hamilton, composed by Edward Elgar, op. 66 (London: Enoch & Sons, 1912); BL 11775.h5/2; hereafter, Hamilton, The Crown of India: libretto.

20. For a discussion of the motivation behind the transfer of the capital, see Cronin, British Policy, 217.

21. Barton, At the Delhi Durbar 1911, 75.

22. Such interpretation of pageants, masques, and other imperial entertainments as pieces of popular propaganda dates back to J. A. Hobson, The Psychology of Jingoism (London: G. Richards, 1901). For more recent examples of this general view see two important books, John M. MacKenzie, Propaganda and Empire: The Manipulation of British Public Opinion 1880–1960 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984); and Imperialism and Popular Culture, ed. John M. MacKenzie (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1986).

23. Hamilton, Crown of India: libretto, 7 and 18. For detailed analyses of the belief systems that justified the Raj, see Thomas Metcalf, Ideologies of the Raj (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995); and Bernard S. Cohn, Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1996).

24. This was how the Illustrated London News described Victoria, Empress of India’s rule of India during the 1886 India and Colonial Exhibition, 8 May 1886; quoted in Kusoom Vadgama, India in Britain: The Indian Contribution to the British Way of Life (London: R. Royce, 1984), 61. In the masque, these sentiments are echoed by “India” as she pays homage to the King-Emperor and Queen-Empress at their feet; Hamilton, Crown of India: libretto, 22.

25. Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (London: Vintage, 1994), 180.

26. Robert Anderson, “Elgar’s Passage to India,” Elgar Society Journal 9, no.1 (March 1995): 15–16.

27. Anderson, Elgar (New York: Schirmer Books, 1993), 16–17.

28. Anderson, “Elgar’s Passage to India,” 16, 19. See also Anderson, “Immemorial Ind,” in his Elgar and Chivalry (Rickmansworth: Elgar Editions, 2002), 312–13. In addition, Elgar would have come to know of the opulence of Indian arts and crafts from his mother, Ann; Anderson notes that she kept a scrapbook of cuttings that included some on Indian art.

29. Elgar clipped and kept the following announcement in The Bystander: “Sir Edward Elgar, strongest and most individual of all English composers, has, by assuming the Order [of Merit], redeemed knighthood from being the charter of mediocrity in music”; 15 November 1911. EBM Cuttings, 1.

30. The presence of Indians living in Britain around the turn of the century, as distinct from the idea of “India” constructed at the exhibitions, was not large. Although no official statistics are available before 1947, the Indian National Congress conducted a survey of “all Indians outside India” in 1932, which estimated 7,128 Indians in the United Kingdom. Some idea of the numbers of Indians in England’s cities can be gleaned from these figures: in 1939 the Indian population in Birmingham was about 100, which included some twenty doctors and students; by 1945 it was 1,000. Of professional-class Indians, the largest group was in the medical profession: it is estimated that before 1947 about 1,000 Indian doctors practiced throughout Britain, 200 of them in London. Three Indians/Pakistanis were elected to the House of Commons between 1893 and 1929. Rozina Visram, Ayahs, Lascars, and Princes: Indians in Britain, 1700–1947 (London and Dover, N.H.: Pluto Press, 1986), 190–94.

31. The Indian Rebellion (also known as the Indian Mutiny) of 1857, began in Meerut on May 10 and spread quickly to the capture of Delhi by the mutineers. The British slaughtered the mutineers, and this act was celebrated as a victory over native resistance. For many in India, the Mutiny was a nationalist uprising against foreign rule and came to be considered the First War of Independence. An enormous amount of writing, British and Indian, covers this important event; it has been acknowledged as having provided a clear demarcation for both Indian and British history; see, for example, Christopher Hibbert, The Great Mutiny (London: Viking 1978).

32. H. Trueman Wood, ed., Colonial and Indian Exhibition Reports (London: William Clowes & Sons Ltd., 1887).

33. The 1901 Exhibition, for example, opened May 2 and closed November 9; it covered some 73 acres in Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Park. Admission was one shilling, season tickets were one guinea. The attendance figures were 11,497,220; profits were £39,000 (pub. figure of 1905). Free music was a big selling point for the exhibition; Perilla and Juliet Kinchin, Glasgow’s Great Exhibitions (Bicester: White Cockade, 1988), 15, 87–88.

34. For instance, a complete “Indian City” was erected for the Empire of India Exhibition in 1895. Raymond Head notes that “the apotheosis of the use of an Indian style at an exhibition was at the Franco-British Exhibition in 1908,” which featured Mughal or IndoSaracenic rather than Hindu forms, in The Indian Style (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1986), 128–29, 141–42. See also Franco-British Exhibition Official Guide (London: Bemrose & Sons Ltd.,1908); F. G. Dumas, Franco-British Exhibition Illustrated Review (London: Chatto & Windus, 1908), esp. 295; Illustrated London News, 15 June 1901; Imre Kiralfy’s notes for his India and Ceylon Exhibition (1896), BL India Office, V 26652, 37–40.

35. John M. MacKenzie discusses these productions in his Orientalism: History, Theory and the Arts (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1995), 194–96; quotation, 196.

36. Imre Kiralfy, India (1895), BL1 1779, Kb, folio 5.

37. Ibid., 41. For a more detailed discussion of Kiralfy’s India, see “The English Musical Renaissance, An(other) Imperial Myth,” in A. Nalini Ghuman Gwynne, “India and the English Musical Imagination,” Ph.D. diss., University of California at Berkeley, 2003, 25–28; see also MacKenzie, Orientalism, 196–97.

38. The reference is to Rudyard Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden: The United States & The Philippine Islands, 1899” which begins “Take up the White Man’s burden/send forth the best ye breed …” in Rudyard Kipling’s Verse: Definitive Edition (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1929).

39. Anderson, Elgar, 35.

40. Crystal Palace Programme and Guide to the Entertainments, 1901, BL Miscellaneous Programmes 1898–1923, Shelfmark 341, no. 4. See also Anderson, Elgar, 36.

41. Sir Henry Wood recalled the historic Promenade Concert held at the Queen’s Hall at which the D major march was premiered and “accorded a double encore”: “The people simply rose and yelled. I had to play it again—with the same result; in fact, they refused to let me go on with the programme… . Merely to restore order, I played the march a third time.” Wood, My Life of Music (London: Gollancz, 1946), 154.

42. Quoted in Anderson, Elgar, 49–50.

43. Robert Anderson surmises that it was probably Clara Butt (rather than King Edward VII) who suggested the use of the trio tune from Pomp and Circumstance March no. 1, in Elgar, 53. For further details on such national and imperial occasions as the 1902 coronation, including the Second British Empire Festival of 1911, see Michael Musgrave, The Musical Life of the Crystal Palace (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), esp. “National and Imperial Festivals,” 211–12. See also David Cannadine, “The Context, Performance and Meaning of Ritual: The British Monarchy and the ‘Invention of Tradition,’ c. 1820–1977,” in The Invention of Tradition, ed. Eric Hobsbawm and Terrence Ranger (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983; repr. 1989), 101–64.

44. Tarak Nath Biswas, Emperor George and Empress Mary: The Early Lives of Their Gracious Majesties the King-Emperor and Queen-Empress of India, rev. Panchanon Neogi, 4th ed. (London: New Britannia Press, 1921).

45. See Cathy Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy, “Survivors of Our Hell,” The Guardian Weekend, 23 June 2001, 30–36.

46. Quoted in Anderson, “Elgar’s Passage to India,” 16.

47. Daily Telegraph, 3 February 1912, EBM Cuttings, 11.

48. Letter (January 1912), reproduced in Jerrold Northrop Moore, Letters of a Lifetime (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), 242.

49. The Crown of India: An Imperial Masque, arranged for the piano by Hugh Blair (London: Enoch & Sons, 1912), 52–64, BL g.1161.e; hereafter, Elgar, Crown of India: vocal score.

50. From a report in The Standard, 1 March 1912; quoted in Moore, Edward Elgar: A Creative Life (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 629. See also EBM Cuttings, 7.

51. Moore, Edward Elgar: A Creative Life, 630.

52. Cited in ibid.

53. Daily Telegraph, 9 April 1912, EBM Cuttings, 23.

54. Daily Express, 12 March 1912, EBM Cuttings, 18.

55. Times (London), 7 March 1912, EBM Cuttings, 15.

56. Franco-British Exhibition held at Shepherd’s Bush, London, 1908, Official Guide, 47–48.

57. The Standard, 1 March 1912; quoted in Moore, Edward Elgar: A Creative Life, 629.

58. The Referee, 17 March 1912.

59. Excerpts from 1912 reviews in the Morning Post (12 March) and the Daily Telegraph, 24 February and 12 March, respectively; EBM Cuttings, 17.

60. “Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus” is another such hymn popular at the time. Hymns Ancient and Modern Revised (London: William Clowes and Sons Ltd., 1950), 872–73.

61. Raymond Monk, ed., Elgar Studies (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1990), app. 1 and 4, 16–33.

62. The quotation from “Land of Hope and Glory” appears in St. George’s final verse to accompany the words “Dear Land that hath no like!” Elgar, Crown of India: vocal score, 61.

63. Gerry Farrell discusses European reactions to kathak in his Indian Music and the West (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 29–30, 54.

64. The O. E. D. definition of nautch: “An east Indian exhibition of dancing, performed by courtesans or professional dancing girls.” Due to the impact of the anti-nautch movement in 1892, the courtesans who danced traditional kathak were stigmatized as the infamous nautch.

65. Walter Henry Lonsdale, Nautch Dance (London: Alphonse Cary, 1896); Frederic H. Cowen, “The Nautch Girl’s Song.” (London: Joseph Williams & Co., 1901).

66. Edward Solomon, The Nautch Girl, comic opera in two acts (London: Chappell & Co., 1891).

67. Richard Burton, Sindh Revisted: In Two Volumes (Karachi: Department of Culture and Tourism, Gov. of Sindh, 1993), 2:53.

68. Unidentified review of The Crown of India Suite performed at the Proms on September 7, 1912, EBM Cuttings, 41.

69. Rudyard Kipling’s “The Ballad of East and West” begins: “Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.” Gunga Din and Other Favorite Poems (New York: Dover Publications Thrift Editions, 1990), 6–9.

70. “Hail, Immemorial Ind!” Elgar, Crown of India: vocal score, 21–31.

71. Scene description for Tableau I, Hamilton, Crown of India: libretto, 3.

72. Hamilton, Crown of India: libretto, 5.

73. For a detailed analysis of Agra’s song, see “Elephants and Moghuls, Contraltos and G-Strings: How Elgar Got His Englishness,” in A. Nalini Ghuman Gwynne, “India and the English Musical Imagination,” 134–63.

74. Agra’s song and the “Crown of India March” can be heard on Classico CD 334 (Olufsen Records, 2000); a 1912 recording of the “Crown of India March” by the Black Diamonds Band was released by the Elgar Society, CDAX 8019, 1997. A new edition of the masque has recently been published that includes Henry Hamilton’s libretto, the orchestral suite of five numbers from the masque arranged by the composer, the vocal score of the masque, and two numbers reconstructed from the extant orchestral parts: Agra’s song, “Hail, Immemorial Ind!,” and “Crown of India March.” The Crown of India, 3rd ed., ed. Robert Anderson (London: Elgar Society, 2005), 18.

75. The Crown of India Suite, op. 66, score (Hawkes and Son, H. & S. 4936), BL h.3930.w.(1.); and orchestral parts, BL h.3930 (42). The suite is published in full score by Edwin F. Kalmus & Co.

76. Elgar conducted the London Symphony Orchestra in the suite’s premiere at the Three Choirs Festival, Hereford, on September 11, 1912; program held at the Elgar Birthplace Museum, ref. 1037. Elgar used the Anglicized spelling Mogul, rather than the correct Mughal.

77. See Elgar’s letter, 13 August 1930, quoted in Moore, Elgar on Record: The Composer and the Gramophone (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1974), 113. The recordings were made between September15 and 18 with the London Symphony Orchestra in the Kingsway Hall. The “March of the Mogul Emperors” was recorded, as was the “Menuetto,” and the “Warriors’ Dance.” These were transferred from shellac by A. C. Griffith to LP (RLS 713). The “Introduction” and “Dance of the Nautch Girls” was also recorded. For further details, see Moore, Elgar on Record, 114–15. See also the letter from Gaisberg to Elgar, 16 October 1930, in Moore, Elgar on Record, 117.

78. Letter from Elgar to Fred Gaisberg, 15 October 1930, in Moore, Elgar on Record, 116.

79. Quoted in ibid., 128.

80. Times (London), 26 April 1915. This concert is described by Jeremy Crump in “The Identity of English Music: The Reception of Elgar 1898–1935,” in Englishness: Politics and Culture 1880–1920, ed. Robert Colls and Philip Dodd (London and Dover, N.H.: Croom Helm, 1986), 164–90, 173. The event was, perhaps, an attempt to bolster public morale during the war years, at a time of increasing pressure for conscription; Crump suggests that the concert was “an apotheosis of self-confident militarism.”

81. British Empire Exhibition pamphlet no. 7: Pageant of Empire Programme—Part II July 21–Aug 30 1924 (Fleetway Press Ltd., London), Elgar Birthplace Museum Concert Programmes 1912, Ref. 1126: 5. The oft-quoted letter that Elgar wrote to Alice Stuart-Wortley deploring the vulgarity of the event might suggest the composer’s renunciation of overt celebrations of the British Empire. See Jerrold Northrop Moore, ed., Edward Elgar: The Windflower Letters. Correspondence with Alice Caroline Stuart Wortley and Her Family (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), 289–90.

82. I have not been able to locate a score of Indian Dawn, nor find any further references to it.

83. Similarly, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s Bamboula represented South Africa in the pageant, along with Hamish McCunn’s Livingstone Episode, Elgar’s “The Cape of Good Hope,” “Dutch Boat Song,” and “Old ‘Hottentot’ Melodies,” et al. Uday Shankar came to London in 1920 to study art; his father, Shyam Shankar produced an Indian ballet in London in 1924 in which Uday danced. Ravi Shankar, My Music, My Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1968), 63.

84. “Elgar’s New Masque,” Daily Telegraph, 24 February 1912, EBM Cuttings, 15.

85. Michael Kennedy, “Elgar the Edwardian,” in Monk, Elgar Studies, 116–17; and Kennedy, notes to CD Hamburg Deutsche Grammophon 413 490–2 (1982) that includes the Enigma Variations, Pomp and Circumstance March, op. 39, along with the Crown of India Suite, Leonard Bernstein.

86. Stanley Sadie, ed., The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan, 2001), 8:125.

87. Hindu Marches by Raymond Roze and Sellenick, 1899. Many other pieces are “Indian” marches in all but name, such as Edward Clarke’s “Song of the Indian Army” to words by B. Britten (London: F. Moutri, 1859). Carl Bohm’s Miniature Suite for piano includes an “Indian March” (Leipzig: Arthur P. Schmidt, 1907). See also Austin C. Ferguson’s Indian Wedding March for piano (London: West & Co., 1914); and John Faulds, The Indian: Grand March for piano (London: E. Marks & Sons, 1913). The spelling of the composer’s name here is not one John Foulds (1880–1939) seems ever to have used, unless it is an error. Foulds scholar Malcolm MacDonald states that, as far as he is aware, there is no mention of such a piece in Foulds’s work lists, and that no work of Foulds is known to have been published by Marks & Son (personal correspondence, 25 May 2006). Foulds did, however, write a “Grand Durbar March” in 1937 when he was in India, which is a suggestive parallel.

88. Along with other Indian exotica, this piece is discussed in Derek B. Scott, The Singing Bourgeois: Songs of the Victorian Drawing Room and Parlour (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1989), 177–78.

89. John Pridham, The Prince of Wales Indian March (London, 1876) and General Roberts’ Indian March (London, 1879). Other examples include Stephen Glover’s The Fall of Delhi “characteristic march for the pianoforte” (London, 1857) BL h.745 (5), and The Oriental March of Victory (London, 1858), BL h.745 (9).

90. Thomas Boatwright, Indian March: The Diamond Jubilee (London: Klene & Co., 1898): BL g.605.k (1). See also Richard F. Harvey, The Royal Indian March for piano (London: Francis Day & Hunter, 1901).

91. “March of the Mogul Emperors” no. 5, The Crown of India Suite, op. 66, full score (Miami: Edwin Kalmus & Co.), 35–53. For an artistic and political study of Mughal court culture, see Bonnie C. Wade, Imaging Sound: An Ethnomusicological Study of Music, Art and Culture in Mughal India (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), which includes an extensive bibliography for further reference.

92. Quotation from Delhi’s speech, First Tableau; Hamilton, Crown of India: libretto, 12–13. These are four of the great Emperors of the Mughal Dynasty: Akbar (reign: 1556–1605), Jehanghir (r.: 1605–27), Shah Jahan (r.: 1627–58), and Aurangzeb (r.: 1658–1707). After the last Mughal emperor, Bhadur Shah Zaffar, was exiled to Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon, Myanmar) in 1858 following his post-Rebellion capture by the British, a formal end was declared to the Mughal Dynasty (that began with Babur in 1526). The title of Emperor of India was eventually taken over by the British monarch (in 1877), in the person of Queen Victoria, and held until India won independence from Britain in 1947.

93. The Kipling quotation, from his poem “A Song of the White Men,” reads: “Oh, well for the world when the White Men tread / Their highway side by side!” Verse (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1954), 280.

94. A five-movement orchestral suite was extracted from Mlada in 1903 and published the next year. Including a suggestively titled “Indian Dance,” Rimsky-Korsakov’s suite concludes with the grand “Procession of the Nobles.”

95. For a detailed tracing of the history of the polonaise in Russia, see Richard Taruskin, Defining Russia Musically (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1997), 281–91.

96. Elgar certainly knew Rimsky-Korsakov’s music: he had conducted the Fantasia on Serbian Themes and the suite from The Snow Maiden in 1899. Monk, Elgar Studies, App. 2, 25.

97. “India,” part of “Greater Britain,” The Sketch 17, no. 221 (21 April 1897): 556–57. Images of Ganesh, the elephant-headed god of the Hindu pantheon, also contributed to The Sketch’s representation of India.

98. Such imagery endures: the cover of Sony’s 1992 recording of The Crown of India Suite (SBK 48265) features a painting of finely decorated elephants carrying Akbar and his cohorts who are engaged in military activities using ornate swords and shields. The painting Akbar, Grossmogul von Indien (1542–1605), is in the Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte, Berlin.

99. Musical Times 53, no. 836 (1 October 1912): 665–66; The Referee similarly spoke of “a touch of the barbaric appropriate to the situation” in the “March of the Moghul Emperors” (17 March 1912), EBM Cuttings, 19.

100. Cecil Gray, A Survey of Contemporary Music (London: Oxford University Press, 1924), 78–79.

101. F. H. Shera, Elgar: Instrumental Works (London: Oxford University Press, 1931), 6.

102. Ronald Taylor, “Music in the Air: Elgar and the BBC,” in Edward Elgar: Music and Literature, ed. Raymond Monk (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1993), 337.

103. Ibid., 336.

104. Alex Cohen, “Elgar: Poetic Visions and Patriotic Vigour,” Radio Times, 2 December 1932, 669.

105. Ibid., 669.

106. Crump, “Identity of English Music,” 184.

107. Ibid., 184.

108. Ibid., 181.

109. Ernest Newman in the Sunday Times (25 February 1934); quoted in Crump, “Identity of English Music,” 180.

110. Frank Howes, “The Two Elgars,” Music and Letters 16, no. 1 (January 1935): 26–29.

111. A. J. Sheldon, Edward Elgar with an introduction by Havergal Brian (London: Office of “Musical Opinion,” 1932), 16.

112. Howes, “Two Elgars,” 26–29.