Figure 10.1 An early adopter of Google Glass (source: Wikipedia).

Throughout this book we have focused on the role of information in human activities, from shopping to governing, arguing for the importance of high-quality information and open access to information when there is no compelling reason for secrecy. We have described tools for improving the quality and the completeness of information in the overall market and particularly in health care, government agencies, and annual reports.

We have also emphasized the recurring theme “information is power,” but of course that isn’t necessarily true. Information can confer tremendous authority at times, and can result in greater awareness and participation. But it can also be trivial, overwhelming, misleading, or incomprehensible. It can be feckless, which is why the better-informed of two political candidates has no guarantee of winning an election; other factors, such as an especially engaging smile, can prove more influential than access to all types of information. And yet the winning candidate will almost certainly make use of potent informational tools—for example, lists of donors, demographic data on voters, social media, opinion polls, and phone banks.

“Information is power” is really our shorthand for something more elaborate and more elusive than the simple phrase suggests. Information is no guarantee of power, just as owning a bicycle is no guarantee that you will use it to speed across town. But the bicycle gives you the potential to move faster and further than you could on foot. Information does the same thing; it makes certain types of power possible. To stretch the analogy even further, a small bike with training wheels can empower a small child in certain ways, but less fully than a mountain bike empowers an adult-sized rider. Information comes in different varieties and flavors, and creates different potential utilities for its end users.

We also have made use of the old engineering adage “garbage in, garbage out.” We find, looking back over what we have written, that “GIGO” is a more universal phenomenon than one might first suppose. Bad input not only confounds computer models; it affects all the systems we have looked at in this book: the health-care system, the Soviet Union, environmental management systems, financial reporting, government bureaucracies, and the economic system as a whole. When information inputs are severely limited—because the information is false (Enron), missing (Starbucks), unnecessarily confusing (hospital bills), too restrictive (environmental regulation), outdated (Soviet Five-Year Plans), confidential (business), or top secret (government)—the outputs from the systems are suboptimal.

By necessity, the decisions based on those outputs are suboptimal as well, creating widespread inefficiencies in how the systems perform. The inefficiencies are ultimately correctable and, in the happiest of situations, can even lend themselves to self-correction. We saw this in the Dupreshi example: The sustainability-reporting mechanism created what can be thought of as a mini-marketplace for information. Everyone “consuming” information from the Dupreshi website had the option of commenting on what information was valuable, what information was credible, and what information was suspect. The dynamics of the site created an incentive for providing additional details and establishing what actually was occurring at the Dupreshi facility. Bit by bit, the process, at its best, separates the wheat from the chaff.

However one chooses to interpret the phrases we have used, the links between high-quality information and the capabilities of institutions and individuals will strengthen in the decades ahead. As ordinary objects become ever more sophisticated conduits for information, society will continue to grapple with the tensions between the empowerment these objects confer and the threats of an expanding information milieu.

Telephones are already sophisticated devices for receiving and transmitting information. Soon other items—refrigerators, televisions, cars—will be hooked in to the information cloud that the Internet is becoming. A nascent technology dubbed Li-Fi even envisions Internet-enabled light bulbs that will not only illuminate our homes and workplaces but also allow high-speed data transmission, even when the lights are turned off. Tiny pill-shaped health-monitoring devices that patients swallow will temporarily transmit medical information, as will smart contact lenses that monitor blood sugar. Wireless implants offer more permanent capabilities.

The innovations on the horizon are wildly interesting and touch upon almost all areas of human activity. Google’s Flu Tracker is an early-warning system for flu outbreaks that takes note of increased activity in Web searches for “flu shots” and similar terms. A site called HealthMap.org takes a more comprehensive approach, consolidating information from searches, news items, official reports, medical forums, and diverse other sources to identify outbreaks of infectious diseases around the world; the site claims to have spotted the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa more than a week ahead of the World Health Organization’s first announcement of it. Information-exchange applications, such as Uber and Lyft, have disrupted industries. Companies are exploring the prospects of using real-time data gleaned from consumers’ photos, sales transactions, and direct data inputs from shoppers to generate instantaneous financial statistics; that, in turn, promises a fuller, faster, more finely detailed picture of inflation data, employment levels, and other changes in the economy well before the Federal Reserve and the Department of Commerce publish their assorted statistical updates.

Of course, changes and innovations that are positive for some industries and some fields may carry significant negatives for others. The taxi industry certainly isn’t enamored with peer-to-peer ride-sharing services, and physicians profess little affection for the complex electronic health-records systems that are coming to dominate the health-care industry. The types of tensions that emerge with new technologies are illustrated, in a small way, by the commercialization of Internet-enabled eyeglasses. Google Glass was the first widely publicized wearable fashion accessory with full Internet capabilities. The somewhat awkward looking but not totally unattractive eyewear offers high-speed wireless Internet access, responds to users’ voice commands, and displays results on one lens. The display is visually equivalent to viewing a 25-inch screen. This compact technological marvel weighs no more than an ordinary pair of glasses.

Figure 10.1 An early adopter of Google Glass (source: Wikipedia).

Functionally, Google Glass isn’t very different from a typical smartphone in its informational capabilities. Both devices can help users find the nearest Chinese restaurant, navigate to grandma’s house, keep abreast of breaking news stories, and take photos and videos at a moment’s notice. It’s that last function that has generated controversy.

A user of Google Glass can take a photograph or begin recording a video with a subtle, almost undetectable command. People generally rely on some visual cues that they are being recorded, such as a camera or a cell phone held in a characteristic I’m-taking-a-photo position. Google Glass offers no such obvious cues. A Google Glass wearer could be recording video images in a locker room, at a confidential business conference, on a beach, or during a casual but presumably private conversation. The technology strikes some as an overly intrusive invasion of privacy. Some restaurants and other businesses have banned the wearing of Google Glass devices on their premises out of concern for privacy, and a few casinos have prohibited it out of a fear of card counting.

The resistance to Google Glass surprises some adherents of the device, since the capability to record almost any situation has existed for years in cell phones and in even smaller devices (such as hidden “nanny-cams “and “spy pen” video cameras). Google Glass, they argue, is no different. But like the automated license-plate-reading cameras we discussed in chapter 8, Google Glass takes capabilities for monitoring to a higher level, even though it merely consolidates several existing technologies rather than creating a fundamentally new form of electronic record keeping. The fate of Google Glass is uncertain, as Google has withdrawn the device from the market, at least temporarily. But the technology will continue to mature, and as devices become lighter, more powerful, and less obvious, and as battery life improves, the appeal of wearable computing is likely to increase and concerns about it are likely to multiply.

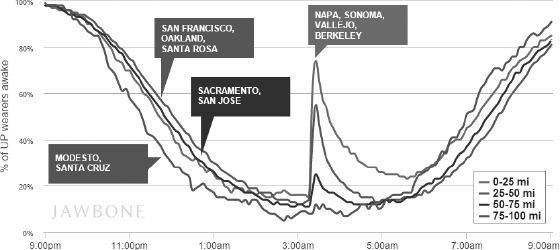

Web-enabled eyeglasses aren’t the only things that are going to give us pause. We are comfortable with the notion that Santa Claus knows when we are sleeping and when we are awake, but will we be so sanguine about the Internet having that information? A day after a strong late-night earthquake rattled northern California, a company called Jawbone published a graph of how the quake disrupted sleep patterns in the area. In Napa Valley, close to the epicenter, 74 percent of people were shaken out of bed; in San Francisco (45 miles away) about 55 percent were awakened; further still, in San Jose, only 25 percent. Jawbone gleaned the data from users of one of its products: a personal activity tracker, worn as a bracelet, that tracks eating habits, exercise levels, and body motions. Although the data Jawbone reported were consolidated and anonymous, they represent a growing phenomenon of people who are always online, even in their sleep.

The emerging era of ubiquitous online connections from a wide variety of devices, dubbed the Internet of Things, will be a substantial factor in the magnification and reshuffling of social power related to information tools.

Consider what an Internet-enabled refrigerator will bring to a household. Efforts to create smart refrigerators have relied on bar-code readers and other identification technologies to keep track of what is stored in them. So far such devices have been clunky, expensive, and unimpressive, but so were the early wearable computers. In the years to come, smart refrigerators will grow more sophisticated, more versatile and cheaper. The technology, if it catches on, will probably track contents in something akin to the way human beings do—for example, by visually “recognizing” a green pepper or a container of orange juice and using available cues to gauge quantity and freshness. These smarter refrigerators will be able to notify owners when it is time to go food shopping, to prepare a shopping list, and perhaps even to do the shopping itself by messaging an order to a supermarket. The system will be able to suggest meals on the basis of the items on hand, and to issue a warning when a certain food or beverage is approaching the end of its shelf life. Chemical sensors could even be on the alert for telltale odors of putrefaction.

A smart refrigerator is more than simply a convenience. The capabilities to track food items, monitor freshness, and make better use of the items on hand make individual consumers more efficient. This is no small achievement. Like the innumerable tweaks we discussed earlier—countless small changes that can lead to a more sustainable marketplace—smart refrigerators could conceivably bring about significant positive changes to our overall food system.

But smart appliances, with always-on connections to the World Wide Web, open doors to other scenarios as well. A refrigerator will become a two-way communication device, not simply delivering information to “you” but sending information to “them.” A refrigerator will come with an end-user licensing agreement, terms of service, and a privacy statement, just as Web browsers, video games, and smartphone service packages currently do. Your food items may become part of your overall demographic profile—for example, if the sensors detect a birthday cake, you may start seeing ads for birthday presents. Certain refrigerated medicines may trigger “helpful” communications from pharmaceutical companies, nursing facilities, or even funeral homes. These advertisements may be displayed on your refrigerator’s built-in screen, may show up in your email inbox, may appear on your smart television, or may be transmitted to any of dozens of other devices.

And darker intrusions will be possible. A smart refrigerator, like any online device, can be “hacked” (although what hackers would do with such access is a bit harder to imagine). Law-enforcement agencies may desire to “search” refrigerators remotely, much as they would do at an in-person search of a home, looking for cash, body parts, or drugs. Spy agencies may search for certain ethnic or foreign-sourced food items as clues to the identity of those using the refrigerator. Landlords may try to track quantities of food consumed as an indication of the number of people living in a household.

There is no way of knowing precisely how any new smart technologies will play out, but it is safe to say that any new technology has ramifications that go well beyond the individual user. Each new information tool plugs its users into a cyber-ecosystem in which no one is quite independent of anyone else. The primary user of the technology—the owner of a smart refrigerator, say—puts its information capabilities to use, thereby enhancing, in a small way, his or her own informational status in the world. But these same capabilities also restructure society in a modest but significant way.

Ideally, smart refrigerators can mean a more effective food system overall, with lower food costs, less food waste, and more efficient use of the energy needed to deliver, store, and dispose of food. Those are good outcomes that benefit society as a whole. In a less-than-ideal situation, however, tensions may arise—between private, commercial, police, and government concerns—that may require public discourse to find the appropriate balance between competing priorities, or (to put it another way) the appropriate balance of power.

As we were drafting this chapter, the shooting of a teenager by a policeman inflamed tensions in the Missouri community of Ferguson and ignited national debates about several matters. One of these matters is purely informational: Should more police be required to wear body cameras so as to record their interactions with civilians? Body cameras are regarded as presenting a much more complete and unassailable accounting of such interactions than witnesses’ personal recollections, with their seemingly inevitable he-said-she-said, yes-he-did-no-he-didn’t quality. The cameras are presumed to have a moderating influence on the behavior of both the police wearing them and the public on the opposite end of the camera lens. When inappropriate behaviors would be unambiguously recorded and deniability would be less available, the inappropriate behaviors of all parties would be minimized—or so it is hoped.

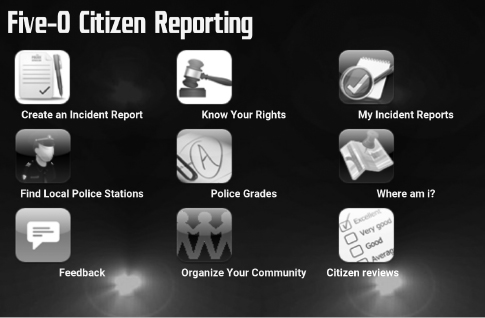

We are intrigued, though, with another tool capable of providing information on interactions between police and civilians: Five-0, a cell-phone app created by a group of teenage programmers. Five-0 is essentially a form that one fills out to rate an interaction with the police. At a minimum, it is a convenient, always-at-hand tool for keeping a methodical record of one’s interactions with the police. It can easily be used immediately after a traffic stop, a stop-and-frisk action, or a response to a 911 plea for assistance. But the potential power of an app like Five-0 lies not in the individual ratings of police activities, but in the consolidation of thousands or millions of such records on the Internet. Five-0 information is designed to provide anonymity to the individuals creating the report, but to be accessible to anyone using the app. Users can view individual reports on individual police officers or can consolidate rankings for entire communities. The app creates “a dynamic grade for courtesy and professionalism” both for individual police officers and for communities. The police force in one town may receive an overall grade of A from citizens pleased with their interactions, while a neighboring town might receive a C and the next town over an F. One wonders what rating the police in Ferguson would have received before the shooting death that triggered months of unrest in that community.

Figure 10.3 A screen shot of the Five-0 app for rating interactions with police.

At the time of this writing, Five-0 has just been released and doesn’t have any track record to speak of. We can only wait and see how widely it will turn out to be used and what effects its use will have. As is true of any online service, Five-0 might well be supplanted by some other tool that grabs users’ attention. But it isn’t difficult to envision that a tool of this sort might enable communities to provide important feedback to their local police about the collective level of satisfaction with police services. Nor is it difficult to imagine websites and news articles along the lines of “The 10 Worst Police Forces in the US” or “The Top Five Police Forces in Texas” that will be based on fine-grained information from Five-0-style feedback.

It seems likely that, at some point, the capabilities of tools such as Google Glass, body cameras, sleep-monitoring bracelets, and Five-0 will merge. When almost everyone is connected to the Internet full time and is able to record interactions, to create reports, and to upload geocoded, anonymous information for the rest of the world to access, it is possible to imagine that everything from police to pedicures to pediatricians will receiving crowdsourced ratings from the masses.

Five-0 and related services are, in essence, people-powered report cards similar to those offered by most shopping websites—for example, Amazon’s five-star rating system, which lets shoppers quickly gauge users’ satisfaction with a product, and which itself served as a starting point for our suggestion of a sustainability rating system based on inputs from users. A patient-based rating system for doctors, clinics, and hospitals could provide information that at present is missing from our health-care system—information that would lead to invisible-hand-style improvements in the market for medical services.

Many factors come into play that might make rating tools useful or render them quite useless. Five-0 could be used to unfairly malign a particular officer or police force if one person were to take it upon himself to file a series of negative reports and organize his friends and acquaintances to do likewise. A police officer might have a grudge against another officer and use the app to file invented complaints. One doesn’t have to read many user-provided comments at Amazon or at other shopping sites to recognize that some of the laudatory comments seem generic, uninformed, and excessive, and to surmise that they probably were posted because a business offered a small benefit to anyone who posted a positive review of the product.

In our imaginary example of the Dupreshi product-sustainability webpage, the users’ comments included information that was directly contradictory to statements from the company, leaving visitors to the site uncertain as to which statements best reflected the true state of affairs. Yet the Dupreshi webpage, taken as a whole, provided useful information. The presence of ambiguous and unverifiable information created a dynamic for self-improvement in the system. A similar dynamic is in play in sustainability ratings, in shopping sites’ product ratings, in sites for rating physicians, and in apps such as Five-0. Amazon would have a hard time staying in business if the information at its shopping site were not reliable. As merchants and users moved to “game” the product-rating system, Amazon took steps to improve its reliability. For Five-0 to be a viable tool in the long term, it would have to do likewise. The same holds true for any other rating scheme.

The examples we have discussed throughout this book have the potential to rebalance societal relationships between individuals and institutions, as do the suggestions we have made for revising information systems in commerce, health care, government bureaucracies, and financial reporting. We would like to close this chapter by stating, as clearly as we can, why such rebalancing is called for.

First, very large institutions are collecting very large banks of data on ever-increasing numbers of people in ever-finer detail. National-security organizations compile data the government deems necessary to protect society from threats of terrorism. Police departments collect data deemed necessary to maintain social order. Government agencies require information needed to collect taxes, to issue drivers’ licenses, and to do various other things that government agencies do. Businesses have been equally productive in finding ways to identify, collect, collate, and analyze huge banks of information on individuals’ creditworthiness, Web and email habits, online and offline spending, educational records, geolocation information, criminal history, property ownership, phone use, legal entanglements, and debt obligations, and are probably collecting equally large amounts of information in categories we aren’t even aware of.

This trend toward amassing large data files in increasingly fine detail for more and more individuals throughout their lives is going to continue, grow more pronounced, and become even more routine as the Internet of Things makes possible the tracking of our individual lives down to daily eating, exercise and sleeping habits. This tracking will take place with very little notice, and will unfold for decent, even noble reasons—the information can be used to provide substantial benefits for everybody, ranging from increased national security to free access to Google Maps, online translations, and other wonderful tools of the Information Age.

But when governments and businesses have a vast, almost endless set of information on each individual, it seems fundamentally necessary that each individual have better information tools with which to understand and interact with governments and businesses. It doesn’t seem likely to us that the informational tools of government agencies and commercial enterprises will be weakened or curtailed in any significant way, so it becomes necessary to strengthen the informational tools available to anyone who wishes to make use of them. If we may belabor our catchphrase one last time, information is power. And power belongs to the people.

Second, we are, admittedly, enamored with the prospects of using information, in a more or less pure form, to bring about positive change. By “pure form” we mean using information itself as the agent of change. This is easily clarified by reference to the Toxic Release Inventory, which we described in chapter 9. Before TRI, agencies created permit programs requiring companies to reduce pollution, and collected information as a means of making sure the requirements were being followed. The environmental permit was the agent of change—the thing intended to modify institutional behavior regarding pollution—and the information was a compliance tool to make sure the intended changes were occurring. TRI achieves much the same end—substantial reductions in toxic chemical releases—not because such reductions were mandated but because the public provision of information (the report-card effect) created a powerful incentive for the reporting companies to reduce the quantities of pollution they released to the environment.

TRI wasn’t the first program that made environmental data available to the public, but it differed from all previous environmental data systems in several important ways. It provided consistent information across all sources, and the data were easily available, with much “friendlier” access tools than older systems offered. TRI also answered questions that were important to the general public, rather than to environmental specialists. Permit writers who collected data wanted answers to questions along the lines of “Is this particular piece of equipment operating within specified parameters before discharging materials into the air or water?” Communities downwind or downstream from a facility were more likely to be interested in questions such as “What is emitted from the plant?” “How much?” and “Are emissions getting larger or smaller with time?”

The ability of information to answer general, obvious questions as well as specialized, arcane questions deserves elaboration because its importance is easily overlooked. We saw this earlier in the Securities and Exchange Commission’s “Show me the money” explanation of financial reports. However, the report from Starbucks didn’t really show the money (not very clearly, anyway), although it displayed a host of fairly minor details about the company’s operations that addressed specialist interests. Shoppers have no way to answer straightforward questions such as “Was this shirt made in a sweatshop?” or “Is this food genetically engineered?” Patients can’t answer very basic questions about health care—“How good is my doctor?” “How much will my treatment cost?”—because the current marketplace simply doesn’t provide information pertaining to those particular questions.

Though we may now be in the Information Age, we haven’t yet learned to give information very much attention. It is still something we get on other topics, but rarely is it the main topic itself. Today’s pre-eminent information managers, librarians, often get requests along the lines of “I’d like some information on China” or “I need information on Ebola,” but we are fairly confident that few librarians have had to field the request “I’d like some information on information, please.” The glare of a very strong spotlight on the technology of information management—storing, moving, securing, and manipulating data—hid in the shadows a weak focus on the information itself—weak enough so that economists could hypothesize about perfect information without ever coming to grips with what even pretty good information looked like in real-world transactions. The American Medical Association can offer the “perfect” DoctorFinder service seemingly without considering what sort of information patients would like to have about the doctors they are about to visit. The Securities and Exchange Commission insists that the rules for financial reporting require companies to “show the money” even while the companies’ reports omit big chunks of the picture of where the money comes from, where it goes, and how it is being used. Government agencies are bound by freedom of information as a means of engaging the public, yet manage to withhold the bulk of the information generated and, in the name of transparency, often provide information that is nearly impossible for the public to make sense of.

Throughout this book, we have made reference to looking at our societal systems through a lens of information. Let’s apply that lens to one final example of a discrete system that serves a valuable function and appears to work reasonably well, but that could be much more valuable and work much better after several improvements.

Consumer Sentinel is a large database maintained by the Federal Trade Commission, the agency that has, in its own words, “championed the interests of the American consumer.” Consumer Sentinel houses the records of millions of consumers’ complaints, detailing allegations of identity theft, telemarketing scams, phony sweepstakes, bogus health products, misleading money-making opportunities, and many other activities. The information is used by law-enforcement agencies throughout the United States and around the world to identify victims of scams and to compile evidence on the nature of various fraudulent activities and the financial losses they cause.

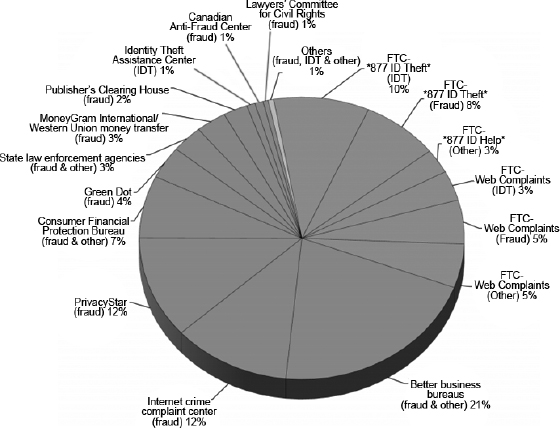

The complaint records contained in Consumer Sentinel originate from a variety of sources. Roughly one-third of the information in the database comes from complaints filed directly with the FTC by means of telephone hotlines, online complaint forms, and other methods. About 5 percent of the complaint information comes from businesses in the private sector, particularly Western Union, Moneygram, and Publishers Clearing House. Almost all of the remaining information fed into Consumer Sentinel comes from governmental and non-profit programs aimed at assisting consumers with fraud complaints.

From an administrative perspective, the collection of information sources—illustrated in more detail on the pie chart from the FTC in figure 10.5—makes good sense. The information providers are largely governmental or quasi-governmental organizations charged with protecting consumers from fraudulent activities and inclined, by their very mission, to share data with one another.

Figure 10.5 Sources of 2.1 million complaints received in 2013 by the Federal Trade Commissions’ Consumer Sentinel.

When we look at this at through an information lens, the perspective changes. Yes, these information providers are valuable sources of information. But are there other potential sources of data that have even better information available? Sources with more records, finer-grained detail, quicker access to complaints data? Sources that can serve as early-warning systems when new scams arise, or when older ones resurface? Think of the experience you may have had when filing a complaint. Was the Federal Trade Commission or your state attorney general’s office your first point of contact, or more a last resort? If you are like most consumers, your initial complaint regarding a disputed charge, if the merchant can’t provide satisfaction, is made to the company that transmitted the billing charge to you—perhaps American Express, Visa, or MasterCard; perhaps PayPal; perhaps a phone company that bills not only for telephone services directly provided but also for third-party services such as apps and games. These firms, by necessity, become referees of sorts between consumers and merchants when charges are in dispute.

Credit-card companies generally keep records of disputes, defer collecting payments on disputed charges, and act as a communications conduit between customers and merchants trying to get disputes resolved. A credit-card company may also act as final arbiter of the dispute, charging the amount back to the merchant so that the customer doesn’t have to pay or determining that a product or a service was appropriately delivered, that the merchant responded to any complaints, and that the customer is responsible for the charge originally billed.

The record keeping involved in tracking and managing disputes is a potential treasure trove of information for the FTC or a similar organization. Any sizable merchant relying on credit cards and online payment services for handling transactions will undoubtedly have a small but steady trickle of transactions that end up being disputed by customers. The presence of outstanding disputes, by themselves, are no reason to suspect a company of wrongdoing; even a million outstanding disputes may not be much of a red flag for a company involved in billions of transactions.

But it would require only a little number crunching of the raw data to see that certain merchants stand out: merchants with an unusually high percentage of disputed transactions, for example, or those with a sudden spike in disputes. A merchant that has, say, 0.1 percent of its charges in dispute may well be statistically typical, whereas 10 percent of charges in dispute is a clear sign that something is terribly amiss—exactly the type of thing that consumers should be alert to, and that the FTC should be looking into. Yet Consumer Sentinel doesn’t take advantage of the rich sources of data that credit-card companies and similar payment processors could provide.

The literature on Consumer Sentinel’s database offers no discussion of why some sources of data are included while others are not. Data from government sources (including the FTC) dominate the system and were perhaps the easiest sources to obtain and integrate into a central database. A smattering of data from Western Union and Publishers Clearinghouse are included, but for the most part data from private firms—including those with the most obvious capabilities for providing dispute-related insights—are missing from the overall picture.

It is easy to imagine obstacles to incorporating private-sector data into a public-sector database: the FTC may not have the authority to compel data submission; consumers’ privacy concerns may stand in the way of data transfer, and costs to both government and industry may pose an obstacle to gathering data and painting a fuller picture of consumer disputes. But it is also possible to imagine solutions to any or all of these concerns that would allow the FTC to overcome obstacles, build a more robust system, and better target merchants for review when their dispute records signal practices causing widespread problems for consumers.

It may also simply be the case that the FTC never thought to include data from credit-card companies and similar commercial sources. Consumer Sentinel has the feel of a government-built system focused on government data sources—a system that expanded to include several non-governmental sources as something of an afterthought. Overlooking what is probably the best source of data on consumer disputes, if that is what occurred, would be a prime example of neglecting to view possibilities through the lens of information.

Consumer Sentinel has another built-in constraint that is worth examining through an information lens: The data in the system are available only to law-enforcement agencies. The FBI, state attorney generals’ offices, local police departments, and computer-crime task forces can access the information. But despite the word ‘consumer’ in the title, an actual consumer wishing to know if a certain business has a large portion of outstanding disputes can’t use Consumer Sentinel to find out.

From an informational point of view, denying access to those who could most make use of the information that Consumer Sentinel provides imposes an unnecessarily severe restriction on the overall flow of information. For example, the FTC relied on internal data when bringing an enforcement case against a company named Your Yellow Pages. The FTC claimed that YYP was engaged in a broad scam to fool businesses, churches and even local governments into thinking a solicitation from YYP was actually an overdue bill for advertising in the Yellow Pages. The YYP solicitation even included Yellow Pages’ well-known “walking fingers” symbol. The FTC shut down YYP’s operations and froze its assets in 2014.

The data in Consumer Sentinel formed part of the basis for the case against Your Yellow Pages. The frequency, nature, and consistency of complaints alerted enforcement officials to potential abuses through misleading solicitations for payment. However, the individuals and small businesses who were solicited by YYP had no way of seeing the red flags, at least not in Consumer Sentinel’s database, since the system is totally closed to public view. Imagine the power of providing consumers with a quick online look-up service so that anyone could check a company’s record.

Through an administrative lens, the self-imposed limitations of Consumer Sentinel’s database make perfect sense. Relying almost exclusively on government sources of data sidesteps the sticky issues of either commanding or cajoling data from the private sector. Restricting data access to law enforcement avoids many of the privacy concerns that would arise from allowing full public access to a database that included private information, such as the names and addresses of the individuals involved in disputes.

But the administrative picture should be seen side by side with the perspectives gained through the lens of information, and some obvious and straightforward questions should be asked: What are the best sources of information on disputes involving consumers? How can the data be put to best use in meeting the interests of the consumers that FTC seeks to serve? Who should have access to the database? Such questions argue for an expanded conception of the Consumer Sentinel effort that would make use of additional sources of information and would allow public access to select portions of the data.

Looking back, we can understand the administrative point of view that created the Consumer Sentinel information system with a strict law-enforcement focus, a highly selective set of information sources, and careful prescriptions as to who can and who can’t access the system’s information.

Looking forward, we can foresee the evolution of a system, with a broader informational focus, in which the most robust information sources are included in the dataset and the information is managed so that a much wider range of users have access to the value—perhaps we should say the power—that the information provides.