CHAPTER 2

Slow Beginnings

The first task was creating the battalion to send to South Africa. Although mostly a volunteer force, as already mentioned, the Battalion had a core of 100 Regular serving soldiers who would act as the leadership and training cadre. The actual mobilization of the 2nd Battalion was astonishingly fast. This was particularly surprising since the unit was made up of eight companies (Coy) that were drawn from across Canada:

“A” Coy raised in British Columbia and Manitoba;

“B” Coy raised in London;

“C” Coy raised in Toronto;

“D” Coy raised in Ottawa and Kingston;

“E” Coy raised in Montreal;

“F” Coy raised in Quebec;

“G” Coy raised in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island; and

“H” Coy raised in Nova Scotia.

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

The RCR

The Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR) is Canada’s oldest serving regular force regiment, formed on December 21, 1883, to instruct the Canadian Militia. The regiment’s first task was participation in suppressing of the North-West Rebellion in 1885. During the short conflict The RCR soldiers fought battles at Fish Creek, Cut Knife Creek, and Batoche.

In 1898 The RCR returned to the North-West, this time to Dawson Creek. The gold rush had attracted thousands of prospectors and entrepreneurs, who flooded into the Yukon Territory to make their fortune, overtaxing the North-West Mounted Police. The government sent in soldiers to help maintain law and order. Once the gold rush died down so did the need for the Royals.

However, the Royals were not idle for long. The war in South Africa prompted Canada to deploy a contingent called the 2nd (Special Service) Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry. It served with distinction during a one-year tour of duty, earning a special parade at Windsor Castle for its part in the victory at the Battle of Paardeberg.

The RCR also served in the First and Second World Wars, participating in many actions and once again serving with distinction. Unfortunately, the postwar peace did not last long. In 1951 The RCR once again deployed overseas, this time in Korea, where they fought a number of key engagements, most notably the battle of Kowang San. For its part in the Korean War, The RCR was awarded the battle honour Korea 1951–53.

Throughout the Cold War (1948–89), as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) faced down the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies, The RCR were active at the Canadian garrison in Germany.

At home, the Royals deployed to Ottawa and Montreal during the October Crisis in October 1970, when FLQ terrorists threatened to spread violence in Ottawa and Quebec to attain their political goals. In the spring to fall of 1990, The RCR assisted when violence erupted in Oka, Quebec. Throughout its history, The RCR also assisted fellow Canadians faced with natural disasters as well as man-made emergencies, such as searching for missing peopled and hunting for fugitives.

The RCR has also participated in many peacekeeping and peace-stabilization missions, including tours in Cyprus from 1964–90 and the former Republic of Yugoslavia from 1991–99. Royals deployed in Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm from 1990–91.

In the new millennium, overseas duty exploded. The RCR sent personnel to Eritrea and Haiti on peace support missions, and has had a heavy presence in Afghanistan since 2006.

Throughout its 128-year history, The RCR has maintained a proud tradition of courage, duty, and professionalism.

On October 23, 1899, the different companies were ordered to assemble in Quebec City. Four days later the Battalion was formally established. Incredibly, the entire unit, numbering 41 officers and 998 enlisted ranks (for a total of 1,039), was loaded onto the SS Sardinian on October 30. The entire force was recruited, equipped, and embarked for deployment to South Africa in less than two weeks.

The troop transport was very quickly dubbed the “Sardine.” It was anything but adequate. The converted cattle ship, reported Lieutenant-Colonel Otter, “proved to be a very slow ship, and greatly lacking in room and accommodation for the numbers on board … sanitary arrangements were particularly bad, and so crowded was the ship that parades or drills were matters of extreme difficulty.”

The troops were even more critical. Private Frederick Ramsay revealed, “We are packed like sardines in our bunks and hammocks.” Arthur Bennett wrote in a letter, “This boat is the greatest old tub to roll that was every built, she rolls around like an intoxicated man if there is the slightest swell…. Some of the fellows had it [seasickness] pretty badly, and for the first day thought they would die, and the next more afraid than ever in case they wouldn’t.” At the time they had no idea that this was a sign of things to come.

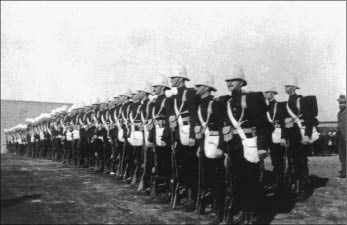

Members of “D” Company on parade.

LAC, C-7981.

When they arrived in Cape Town it became clear to the Canadians that the war was not going well. They soon heard how the Boers had repeatedly beaten the British Field Force.

The inexperienced Canadian volunteers entered what appeared to be a desperate struggle against a wily and very capable enemy. Nonetheless, the “green” Canadian soldiers were eager to get in to the fight. The Battalion disembarked at Cape Town on November 30, but it was not allowed to linger long. The desperate situation in the field necessitated their presence at the front. They entrained the next day for Belmont. But contrary to their expectations and desires, they were not deployed to battle. Instead, they spent the next two hot and monotonous months securing the lines of communication. Their battles were more with boredom, hunger, and the harsh environment than with the Boers. These conditions very quickly created morale problems.

IMPORTANT FACTS

SS

The SS Sardinian, dubbed the “Sardine” by the troops because of its inadequate size and facilities.

LAC, PA-212769.

The SS Sardinian was built in 1875, for the Allan Line Steamship Company, as a passenger cargo vessel. The Allan Line of steamers was well-known at the turn of the century. Sardinian was 400 feet long and 42.3 feet wide. She made her maiden voyage from Liverpool to Quebec City and Montreal.

In addition to transporting Canadian soldiers to South Africa in 1899, the Sardinian also holds a special place in Canadian history. In 1901 the steamer carried Guglielmo Marconi and his radio equipment to Newfoundland. There, Marconi climbed to the top of Signal Hill, at the entrance to St. John’s harbour, and made the first transatlantic radio transmission to Europe.

The Sardinian was sold to the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company in 1915, resold to Astoreca Azqueta, in Spain, in 1920, which reduced her to a coal hauler, then resold again to Compania Carbonera in 1934, and final sold as scrap in 1938.

Outpost duty was both demanding and particularly tedious. “Our present duties has I think a depressing effect upon the men — these duties consist of outpost fatigues and working parties and are very heavy,” Otter wrote in the unit report. Private Ramsay explained, “We sleep in our tents with most of our clothes on and our accoutrements at our side…. I haven’t had my boots off for nearly two weeks and have forgotten what a bath is like.”

Map by Chris Johnson.

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

Battle Honours of The Royal Canadian Regiment

(Italics indicates those Honours emblazoned on the Regimental Colours)

Northwest Canada

1. Saskatchewan

2. North-West Canada, 1885

South Africa

3. Paardeberg

4. South Africa, 1899–1900

First World War

5. Ypres, 1915

6. Gravenstafel

7. St. Julien

8. Festubert, 1915

9. Mount Sorrel

10. Somme, 1916

11. Pozieres

12. Flers-Courcelette

13. Ancré Heights

14. Arras, 1917

15. Vimy, 1917

16. Arieux

17. Scarpe, 1917

18. Hill 70

19. Ypres, 1917

20. Passchendaele

21. Amiens

22. Arras, 1918

23. Scarpe, 1918

24. Droucourt-Queant

25. Hindenburg Line

26. Canal du Nord

27. Cambrai, 1918

28. Pursuit to Mons

29. France and Flanders, 1915–18

30. Landing in Sicily

31. Valguarnera

32. Agira

33. Adrano

34. Regalbuto

35. Sicily, 1943

36. Landing at Reggio

37. Motta Montecorvino

38. Campobosso

39. Torella

40. San Leonardo

41. The Gully

42. Ortona

43. Cassino II

44. Gustav Line

45. Liri Valley

46. Hitler Line

47. Gothic Line

48. Lamone Crossing

49. Misano Ridge

50. Rimini Line

51. San Martino-San Lorenzo

52. Pisciatello

53. Fosso Vecchio

54. Italy, 1943–45

55. Apeldoorn

56. North-West Europe, 1945

Korea

57. Korea, 1951–53

The harsh environment and the inadequate logistical support also tested the troops. From the first day the Canadians faced conditions they would soon become only too familiar with. “Little or nothing to eat, stinking slushy water to drink, no tents for shelter on a hot summer day in Africa and a terrible rain storm,” reported one participant. And when it was not raining there was the other constant irritant. “There is nothing but sand, sand, sand and a few little tufts of sage brush here and there and then there are sand storms,” complained Private Jesse Briggs. “They are dense, choking, blinding and penetrate every crevice.”

The South African environment was also very hard on the clothing. “The wear and tear upon clothing and boots is excessive and Canadian made clothing (khaki) is very much inferior to the English,” stated a unit report. Both of these issues would become very problematic in short order.

The shortage of food was another major aggravation. “Things are going from bad to worse here in the way of grub,” complained Private Bennett. “We are on poor rations and we are even on water rations.” On a number of occasions Bennett passed on advice to those who may have been considering volunteering for the Second Contingent: “Well if the boys took my advice they would stay at home … for there is nothing here but a burning sun and desert storm…. This is the most forsaken country I have ever seen.”

Lieutenant-Colonel Otter was another major aggravation. “How the boys dislike that man,” revealed Private J.A. Perkins. Although experienced and a skilled trainer, he was dour and uninspiring. The men found him rigid and uncompromising. They chaffed at his discipline and endless drill. One letter home revealed a common complaint:

The Colonel, who commands this regiment has lately taken it into his head that a march every day would do us some good and harden our feet, so at 4.30 p.m. every day we are paraded and marched off under the burning sun, over rocks and sand for about 10 miles, getting back about 8 o’clock, which gives us exactly half an hour to get our supper and fix our blankets before the bugle sounds “lights-out.” We are, of course, wet to the skin with perspiration and have no time to change, so sleep in our wet things, and as it gets cold as the deuce at night, the boys are all getting cold.

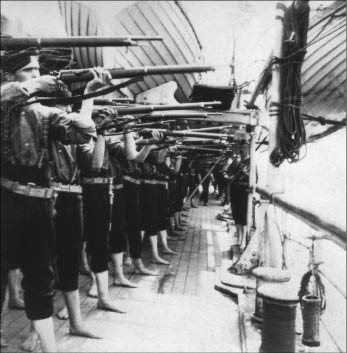

RCR troops doing rifle drill onboard the SS Sardinian, en route to South Africa.

Photographer James Cooper Mason, LAC, PA-173032.

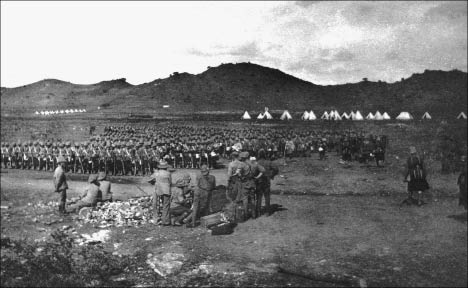

RCR camp at De Aar, South Africa, 1900.

Photographer S.M. Rogers, PA-185357.

They resented Otter’s refusal to allow a dry canteen where additional food and drink could be purchased by the hungry troops — even though all other regimental camps had them. He would not even allow the YMCA to provide such a service. The men also felt he did not push his British superiors for better, more active employment. “I don’t think much of Colonel Otter…. The boys call him the Old Woman and many other pretty stiff names,” confided one soldier in a letter home. “He is too fond I think of giving the men too much marching, and that at a time when it interferes with a fellow’s grub time.”

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

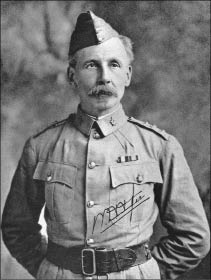

General Sir William Dillon Otter

Lieutenant-Colonel W.D. Otter, Commander First Canadian Contingent, the 2nd (Special Service) Battalion, The RCR.

LAC, C-20010.

General Sir William Dillon Otter was born on December 3, 1843, near Corners, Upper Canada (present-day Ontario). He began his military career in the Toronto militia in 1864, when he joined the Queen’s Own Rifles. In 1866, as the unit’s adjutant, he saw his first action at the Battle of Ridgeway when the unit deployed against the invading Fenians. In 1883, when Canada established a small permanent force, Otter was appointed as the commander of the infantry school depot in Toronto. Two years later, Otter was sent to the North-West to serve in the North-West Rebellion.

Given command of a column to relieve the town of Battleford, Otter precipitated a battle at Cut Knife Creek, which he lost. His choice of ground, ineffective cannon, and a very mobile enemy who maximized the use of terrain caused him to suffer a humiliating defeat. This did not hurt his career. In 1893 he was appointed as the first commanding officer of The Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry, and six years later, in 1899, the government selected Otter to lead the 2nd (Special Service) Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment (2 RCR) overseas during the second Anglo-Boer War. Although he was unpopular with his troops, Otter and 2 RCR were highly regarded by their British commanders. In 1908 he became the first Canadian to command the nation’s military forces. He retired in 1910. However, he came out of retirement during the First World War (1914–18) to command internment operations of enemy nationals resident in Canada.

Otter was knighted in 1913. In the aftermath of the First World War he chaired the “Otter Commission,” to aid in the continuation of Canadian Expeditionary Force units that served overseas. He was promoted to general in 1923. Otter died on May 6, 1929.

The fact that Otter was the interim commandant of Belmont Station did not help matters. His seemingly preoccupation with garrison duties and mundane training created resentment. The eventual arrival of the British appointed commandant, Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Pilcher, just enflamed the problem. Within his first week, Pilcher organized a flying column that included “C” Company, The RCR, and launched a highly successful strike against a group of Boers who were conducting operations near the town of Douglas.

IMPORTANT FACTS

Kopje

Kopje is the term used to describe an isolated granite formation, such as a rock hill, ridge, or small mountain that rises abruptly from the level surrounding veldt in southern Africa. Kopje is originally a Dutch word from which the Afrikaans term koppie was derived.

On January 1, 1900, Pilcher’s flying column surprised the Boers at Sunnyside Kopje. As the artillery shelled the unprepared enemy, the Royal Canadians seized a small kopje, 1,200 metres from the enemy position, and opened fire on the Boers. As the other British forces closed the noose on the Boers, the Canadians advanced on the enemy position, closing to approximately 200 metres and awaiting the order to charge. However, after four hours of fighting and being almost totally surrounded, the Boers fled toward Douglas. The fight had been a great success. The small British force had killed six enemy, wounded 12, and captured 34.

This engagement represented the first experience under fire for the Canadians, yet they seemed to have conducted themselves well. “Although the fire of the Boers was apparently very hot for a time,” reported Otter, “LCol Pilcher who commanded the flying column … speaks very highly of the steadiness under fire and general good conduct of the Royal Canadians during this special service.”

The attack at Sunnyside simply increased the grousing. It was not lost on The RCR soldiers that Pilcher, even though he had just become commandant of Belmont Station, spent his time planning and conducting offensive operations instead of doing administrative tasks. Not surprisingly, the criticisms of Otter continued and grew.

IMPORTANT FACTS

The Battle of Ridgeway

The Battle of Ridgeway was fought on June 2, 1866, near the town of Fort Erie, Ontario. The battle occurred when the town was raided by Fenians.

The Fenian brotherhood was established in Ireland in 1858, in order to free Ireland from British rule and establish the Republic of Ireland. John O’Mahony, leader of the U.S. branch, thought that a Fenian occupied Canada could be traded for a free Ireland.

Approximately 1,000 Fenians crossed the border and occupied Fort Erie on June 1, 1866. That night they marched to present-day Ridgeway. The next morning approximately 850 Canadian militiamen attacked. At first the Canadians seemed to be winning, but the tide quickly turned and the Fenians chased the Canadians off the battlefield with bayonets. The Fenians then burned the town of Ridgeway to the ground and withdrew to Fort Erie. Nine Canadians were killed and approximately 37 were wounded. The Fenian casualties were unknown, although Canadian sources stated that at least six were killed.

The Canadian defeat was embarrassing but not surprising. Compared to the battle-hardened war veterans serving with the Fenians, very few of the Canadian militia troops had actually practiced firing live rounds.

The Fenian force defeated another smaller Canadian contingent (a company of the Canadian volunteer Welland Field Battery and the Dunnville Naval Brigade) later that day in Fort Erie. However, realizing that a large reinforcement of British regular troops was on the way, the Fenians quickly withdrew across the river to return to the United States.

But the expectations of the soldiers were somewhat misguided as well. Their inexperience could be fatal. Otter’s memories of the fight at Ridgeway in 1866 against the Fenians, and later combat in the North-West Rebellion in 1885, taught him the importance of drill, discipline, and fitness. His emphasis on marching and battle drill, specifically the new “rushing tactics” that stemmed from the lessons of the defeats of Black Week, was instrumental in preparing the Royal Canadians for their upcoming campaign. So were the occasional forays into the outlying areas on reconnaissance. These activities improved the physical endurance of the troops and gave them experience in operating in the harsh environment, as well as a better knowledge of the country and terrain. As late as February 11, Otter noted, “I confess to being somewhat disappointed in the condition of many of the men … I find that there are many who it is unsafe to put upon any extra strain for the reason that they are constitutionally unable to meet it.” Therefore, this initial period, as monotonous as it may have seemed, was instrumental in preparing the men for what lay ahead.

IMPORTANT FACTS

The North-West Rebellion

The North-West Rebellion was a short and unsuccessful uprising by the Métis and First Nations of the current province of Saskatchewan in 1885. The Métis and Native peoples were frustrated with the increased settlement of their lands and the reduction of the buffalo herds. Although they appealed to the government to protect their rights and land, little was done. In 1884, Louis Riel took up their cause, as he had done in 1869–70 during the Red River Rebellion in Manitoba. On March 8, 1885, Riel called a meeting and passed a 10-point “Revolutionary Bill of Rights,” for the Métis. Ten days later Riel announced the creation of a provisional government under his control, which included its own armed force held at Batoche. Riel sent a force to Duck Lake, midway between Batoche and the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) garrison at Fort Carlton. On the morning of March 26, 1885, Riel’s force engaged the NWMP force. After a short skirmish, the NWMP force withdrew. In total, nine volunteers and three police were killed. Riel’s group lost six dead.

Using the new CPR rail line, the government dispatched approximately 3,000 troops to the west to reinforce the 1,700 men already stationed there, giving Major-General Frederick Middleton, the commanding general, almost 5,000 soldiers.

Throughout that spring and summer many battles and skirmishes were fought. In the end, the government forces prevailed. By the end of August, the Canadian troops sent to put down the rebellion had returned home.

Louis Riel was tried for treason in front of a jury of his peers. He was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. His execution was postponed three times to allow for appeals and to determine his level of sanity. However, Riel was hanged at Regina on November 16, 1885. As for the Native key leaders, Poundmaker and Big Bear were also tried and sentenced to three years in prison.

The adage “be careful what you wish for” never rang more true. The Battalion clamoured for action and they would soon realize their wish. On February 12, 1900, the Battalion moved to Graspan and joined the 19th Brigade under Major-General Horace Smith-Dorrien. The Battalion now began an epic campaign. Lord Robert’s army of 35,000 men was set to march to Bloemfontein, which would effectively relieve the siege of Kimberley and Ladysmith since it would force the withdrawal of the besieging Boer armies from their positions of vantage in Natal and Cape Colony or risk themselves being cut-off and surrounded. The march, however, would be done without railway support. This necessitated the bare minimum of supplies. Tents, extra equipment, and all other superfluous materials were left behind.

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill was an adventurer, artist, military officer, journalist, politician, and statesman. He is best known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War, when he served as the British prime minister. He was born the aristocratic family of the Duke of Marlborough on November 30, 1874. As a junior officer in the British Army, he participated in combat in India, the Sudan, and the Second Anglo-Boer War, where he was captured by the Boers and later escaped. He became a well-known writer and war correspondent as a result of his writings about the campaigns that he both witnessed and participated in. In fact, he remains the only British prime minister to have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. However, he is most well known for his achievements during his fifty years in politics. He held various key positions during peace and both world wars.

Churchill, who died on January 24, 1965, is considered among the most influential men in British history.

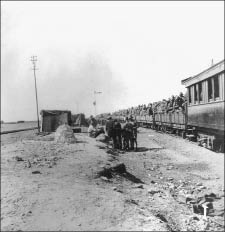

Rail move to the front. Note how the soldiers were packed into open rail cars.

LAC, PA-181416.