CHAPTER

10

From Racial Discrimination to Class Segregation in Postcolonial Urban Mozambique

In 1968, Sebastião Chithombe left his family's farm in Mozambique's countryside and headed for the city of Lourenço Marques. Mozambique, stretching some 1,500 miles along the coast of southeast Africa, was at the time a colony of Portugal; Lourenço Marques, in the far south, was its capital. Chithombe was 14. He came to the city hoping to earn some cash, buy shoes and nice clothes, and then return to his parents’ fields. But staying in the city soon became its own justification.

Chithombe's first home in Lourenço Marques was in the backyard of the Portuguese-owned cantina where he worked, at the edge of the city's shantytowns. Within a year he moved into the shantytowns, to a ramshackle compound built of zinc panels where he shared a small airless room with several other young men. There was no furniture. Between them they had a coal-burning stove, a cooking pot, dishes, a pail to fetch water with, and two reed mats for the five of them to sleep on. Chithombe opened a stall at a local market, made more money, and over the years moved into one larger room in the compound after another. By 1974, he was sharing a two-room unit with his brother. The roof did not leak as much as the other rooms he had lived in.

Mozambique became independent of Portugal in June 1975. In the months leading up to the scheduled handover, most of the Portuguese population left, many going to Portugal and many to neighboring South Africa. In Lourenço Marques, most whites lived in what was colloquially known as the City of Cement, the formalized part of the city, and as they departed, some left their homes in the care of African friends or employees. One of Chithombe's friends was gifted an apartment by a Portuguese friend. When Chithombe visited his friend at his new home, it was the first time Chithombe had ever been inside an apartment in the City of Cement as a welcome visitor, rather than as a laborer. The experience was bewildering. Entering through the apartment's front door, rather than the servants’ entrance, Chithombe went to the bathroom and washed his hands. “It was the first time I'd ever been in a bathroom like that for a reason other than to wash the floors,” he said in a recent interview. In the living room he turned the light switch on and off. He took pride in knowing the light was “ours,” even though the apartment was not his.

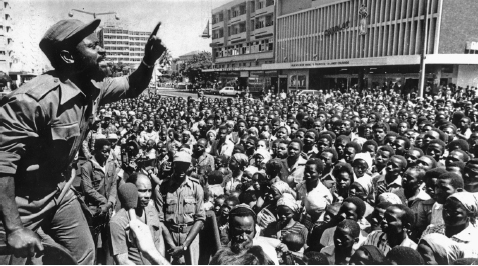

Chithombe and thousands of other shantytown residents were soon offered an opportunity to acquire an apartment of their own in the City of Cement. On February 3, 1976, Chithombe was listening on the radio to Samora Machel, Mozambique's first president, as he spoke before thousands of supporters in a plaza at the edge of the city. Since independence from Portugal the year before, Frelimo, the armed independence movement Machel led, and which now governed the country, had nationalized all land, health clinics, schools, and even funeral parlors. Now the moment had come to nationalize rental housing. With most of the city's white population now gone, tens of thousands of homes and apartment units in the City of Cement were available for occupation. “The city must have a Mozambican face,” declared the president. “The people will be able to live in their own city and not in the city's backyard!” (Machel 1976, 69). Lourenço Marques, Machel announced, would now be called Maputo.

If one were to write a global history of white flight, it might begin with a chapter on U.S. cities in the 1950s and 1960s, when court-mandated school integration and federal subsidies of suburbanization encouraged many white residents to leave urban centers and black neighbors behind. It would also have to include a chapter on South Africa in the 1980s and 1990s, as the fortified edifice of apartheid began to crumble and whites fled behind the walls of gated suburban communities. These are classic examples, and the similarities between them are clear: just as racial segregation was weakened, a new form of racial segregation took shape. The most dramatic episodes of white flight, however—dramatic because of how quickly and completely they took place—may have been those witnessed in the settler cities of colonial Africa during the era of decolonization. This chapter is about one of these cities. In Maputo in the mid-1970s tens of thousands of white residents didn't just pack up and move down the highway, but rather removed themselves from the country en masse and nearly overnight. Post independence Maputo raises an intriguing question about race and the urban landscape: What happens to racial privilege when there is no longer a privileged race?

There are only a handful of cities that share circumstances roughly comparable to Maputo's: cities such as Luanda, capital of Angola (which also became independent from Portugal in 1975), and the larger coastal cities of Algeria, from which the French withdrew in 1962 (Greger 1990; Lesbet 1990). Like Maputo, these were sizable African cities developed for the almost exclusive use of white settlers. Indigenous populations lived mostly in outlying shantytown slums (and in the case of Algiers, a centrally located ghetto as well). And these cities were all abandoned so rapidly that there was no significant period of transition from one situation to another; there was neither meaningful racial integration nor gradual racial turnover. In mid-1974, a year before Mozambique's independence from Portugal, a large majority of residents of the City of Cement—perhaps 70,000 people—were white (Rita-Ferreira 1988). By mid-1976, a year after independence, a large majority of residents of the City of Cement were black.

Rarely has a city found itself in a position to so utterly reorient itself. Nonetheless, the City of Cement remained a zone of privilege. It became the home to party elites, war veterans, military families, and those with better salaried work, generally as government functionaries—Mozambique's nascent African middle class. For most shantytown dwellers, the City of Cement remained out of reach. Many never even considered the possibility. Sebastião Chithombe, for instance, never did.

This chapter draws heavily from Lefebvre's (1991) and Foucault's (1980) insights regarding space: how the urban landscape, rather than simply reflecting existing social inequalities, at the same time, engenders them. This dynamic, furthermore, has as much to do with competing conceptions of the city as with the physical reality of the city itself—conceptions, for instance, of what constitutes modernity and civilization, and ideas about who is sufficiently “modern” or “civilized” to deserve the amenities of urban life. A central theme of this book is how such inequalities, once embedded in the urban environment, manage to persist, though perhaps in different forms. Maputo represents an extreme case in this regard.

It would be difficult to find circumstances that, at first glance, seemed more favorable to undoing a grossly unequal system of housing than the conditions that prevailed in Maputo in the years after independence. Following the Portuguese flight, Maputo was given what seemed to be a virtual blank slate, and it was governed by staunch Marxists often disposed to treating class privilege as a crime. Yet the new regime decided that for the tens of thousands of houses and apartment units of the City of Cement to be of any use at all they would need relatively privileged tenants capable of paying a rent sufficient to maintain them. And even when rents were lowered, most people still couldn't afford to live there. That Maputo remained during this revolutionary period a largely dual city, divided between the formal City of Cement and its shantytowns and, to a significant extent, between two different ways of life, lends further confirmation to just how rigid a social hierarchy can be once it has been reinforced in concrete.

Portuguese Colonialism, Whiteness, and Racial Segregation in Urban Spaces

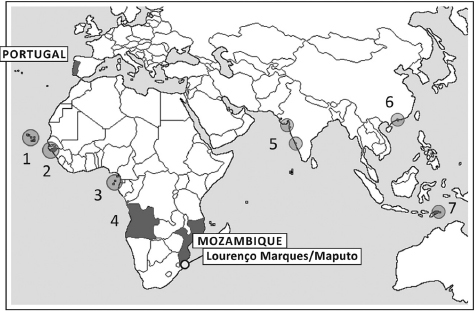

Portugal is today, a small, economically marginal country on the western edge of Europe. It also had a marginal economy when it was one of the European powers claiming a controlling stake in Africa—the unlikeliest member of a select club. Portugal's African colonies in the twentieth century were a vestige of its dominance in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when Portugal maintained a mercantilist empire with a truly global reach (Boxer 1973). Portuguese caravels were the first European vessels to explore the West African coast and, in 1497, to venture beyond the continent's southern tip, opening a seaborne trade with India and the Far East. Portugal initiated the trans-Atlantic slave trade as well, shipping Africans from present-day Angola and other parts of the west coast of Africa to Portugal's vast sugar plantations in Brazil. Dutch and English sea power eventually muscled Portugal out of most markets. The independence of Brazil in 1822 rendered Portugal's long and steep decline irreversible. Portugal nonetheless held on to a number of territories in various far-flung corners of Africa, India, and Southeast Asia.

For centuries, the Portuguese presence in these places was confined mostly to coastal towns and fortified trading posts. But in the late nineteenth century, during the Scramble for Africa, competition from Britain, France, and Germany threatened Portugal's tenuous positions on the continent. Only then was Portugal compelled to move beyond its coastal enclaves and exercise direct control over the interior of Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea, for fear that one of the other European powers would claim them instead. With most local populations in the various hinterlands violently “pacified” and the boundaries of European control settled, Mozambique and Angola became Portugal's most populous and important colonies. White settlement, however, proceeded slowly until the midtwentieth century, when Lisbon sponsored a series of ambitious efforts to encourage immigration from the metropole to its territories overseas. By the eve of independence, the white population had reached 190,000 in Mozambique and 324,000 in Angola (Castelo 2007).

Figure 10.1 Portugal and its possessions in the twentieth century. Key: 1. Cape Verde, independent in 1975; 2. Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau), independent in 1974; 3. São Tomé and Príncipe, independent in 1975; 4. Angola, independent in 1975; 5. Diu, Daman, and Goa, annexed by India in 1961; 6. Macau, transferred to China in 1999; 7. Portuguese Timor (now East Timor), independent in 1975. (Credit: Luciana Justiniani Hees and Wikimedia Commons)

Portugal's long colonial career entered its terminal phase in 1961. That year, an armed revolt shook Angola and India annexed Portuguese possessions on the Indian coast. As in Angola, guerilla-based independence movements were soon launched in Guinea and then Mozambique, and Portugal waged three wars in Africa for more than a decade. In 1974, a coup in Lisbon led by left-wing army officers toppled Portugal's right-wing dictatorship, and the independence of Portugal's five African colonies— which also included two small island groups—followed in late 1974 and 1975. Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea-Bissau (as it was now called) entered the community of nations as some of the poorest, most underdeveloped countries in the world. (Perhaps the true end of empire, however, was in 1999, when Portugal's last colonial enclave, Macau, a city near Hong Kong, was ceded to China, 502 years after Vasco da Gama's first journey past the Cape of Good Hope.)

Portugal had been the first Europe-based power to colonize sub-Saharan Africa, and it was the last to leave. Portugal's tenacious staying power was a testament to the dominant role the colonies played in the imagination of successive Lisbon regimes; the country's future was said to depend on the preservation of an empire that echoed its heroic “Age of Discoveries” of centuries before (Duffy 1962). An oft-used item of propaganda, from the Colonial Exhibition held in Porto in 1934, showed Portugal's various possessions superimposed on a map of Europe and covering an area stretching from the Iberian Peninsula to Russia (Cairo 2006). The map's title: “Portugal is not a small country.” Despite Portugal's past exploits, however, and despite the accumulated landmass flying its flag, Portugal itself remained a poor backwater, economically dependent on Britain. For centuries successive Lisbon governments struggled to raise the capital and maintain the administrative capacity to profitably exploit the colonies to Portugal's benefit. Colonialism often seemed to be an enterprise far beyond its means (Duffy 1962; Isaacman and Isaacman 1983; Newitt 1995; Castelo 2007).

After World War II, perhaps what most distinguished Portuguese colonialism in Africa from practices in other European colonies, and which for a time made Portugal something of a pariah nation, was the institution of forced labor. This was known in Mozambique as chibalo. According to laws in effect since the late nineteenth century, virtually all Mozambican men were subject to long spells as plantation workers or dockworkers or ditch diggers, and with men compelled to work away from home, or to flee Mozambique altogether, women were often left with the sole burden of compulsory cotton cultivation on their own small family fields (Penvenne 1995; Isaacman 1996; Sheldon 2002).

Chibalo differed from slavery; terms typically lasted six months (though sometimes years), and there was nominal compensation (which was often not paid). Like slavery under the Portuguese, the mortality rate on work gangs was high, and as one dissident Portuguese general put it in 1961, at least with slavery, masters valued their assets (Castelo 2007). Even after the official abolition of chibalo in 1961, long after the practice had been officially abolished in other European colonies in Africa, forms of coercive labor persisted in the countryside until independence (Vail and White 1980; Munslow 1983).

Other European colonial powers frequently portrayed Portugal as back-ward and inhumane and undeserving of its African possessions, and in the 1950s and 1960s, as the French, British, and Belgians departed Africa and their colonies became independent, Portugal faced mounting international pressure to do the same. The Portuguese regime stubbornly resisted. Lisbon argued that the Portuguese were exceptional, particularly suited for colonization in ways the other European powers had not been (Duffy 1962; Bender 1978).

Portugal's argument boiled down to a question of race. The Portuguese, asserted the regime's propagandists, had demonstrated over the course of centuries a genius for assimilating different cultures and peoples into Portuguese civilization. Large mixed-race populations in Brazil, Angola, and elsewhere were supposedly testament to Portugal's history of harmonious racial relations (Andrade 1961; Godinho 1962; Freyre 1961; Boxer 1963; Bender 1978; Castelo 2001). To advance this claim, a 1951 constitutional makeover changed the status of the African territories from “colonies” to “overseas provinces” of a single multicontinental, multiracial Portuguese nation. And following reforms in the 1960s, the laws of Portugal recognized as legal Portuguese citizens all those who lived within its many borders. The international community was generally cold to Portuguese claims. They saw African societies dominated and exploited by white minorities.

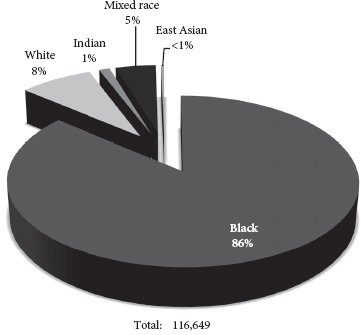

Declarations of racial harmony were in any case of little significance to the millions who lived in Mozambique's countryside, where in the 1960s perhaps one in three children died before the age of five and illiteracy neared 100 percent (Garenne, Coninx, and Dupuy 1996; Cross 1987). Only a small percentage of Mozambicans, fewer than 10 percent, lived in urban areas (Pinsky 1985). But the Portuguese presence was felt most directly in cities, where white populations were concentrated. Segregated Lourenço Marques cast in particularly sharp relief the contradictions of what Lisbon insisted was the colorblind character of its rule.1 The population of Lourenço Marques, it must be said, could by no means be described in simple black and white. The 1960 census for both the city and shantytowns registered 41,165 whites, the vast majority of them Portuguese (Direcção Provincial dos Serviços de Estatística Geral 1960). Among recent arrivals to the city, some had been peasants in the Portuguese countryside who came and worked in cantinas or as day laborers, and some were young professionals or military men with their families, sent from Lisbon to work as government administrators (Castelo 2007). Others were second-and third-generation laurentinos who had never seen Portugal, and who worked in mid- and low-level jobs in the civil service or as shop-keepers or as railroad workers.

Since at least the early nineteenth century, cities all along Africa's Indian Ocean coast possessed significant Indian populations, and Lourenço Marques—with 6,565 Indians in 1960—was no exception. As elsewhere on the coast, many were involved in retail and other forms of trade, particularly in businesses with an African clientele, and occupied a kind of middle ground in colonial society: able to exercise great mobility in the economic sphere, though often marginalized as outsiders in civic and political affairs (Pereira Bastos 2005). The census also registered a small population of Chinese, like Indians largely involved in retail trade.

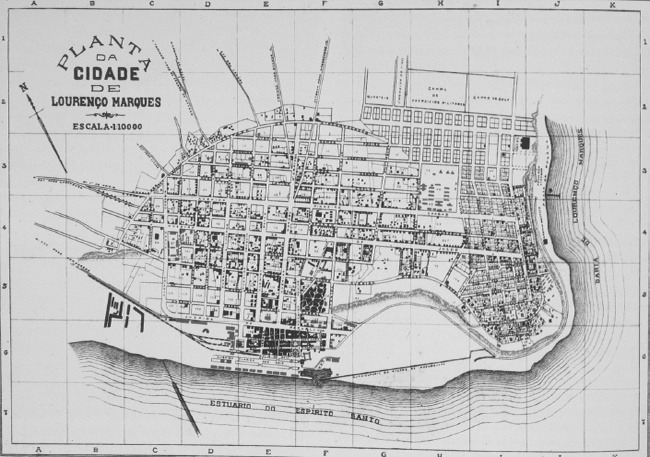

Figure 10.2 The city of Lourenço Marques in 1929, showing the curving street, later called Avenida Caldas Xavier, that divided the formalized city from its shantytowns. The shantytowns are represented in the map by blank spaces. (Credit: Morais 2001)

For a long time Portuguese immigrants to Mozambique were predominately men, and there were a number of people descended from the unions of these men and African women (Castelo 2007). In 1960, there were 7,440 residents of mixed race living in Lourenço Marques. Their level of schooling and employment, and thus their social standing, often depended on their relationship to white fathers (or kind-hearted godfathers), some of whom maintained multiple households—one with a white wife in the city, the other with an African companion in the slums (Honwana 1988; Penvenne 2005).2 The rate of children born from interracial relationships in Lourenço Marques declined dramatically following World War II as more white women immigrated to the city, the white community grew, and with it the social stigma attached to unions that did not propagate whiteness (Castelo 2007).

The 1960 census counted 122,460 blacks living in Lourenço Marques. Most Africans in Lourenço Marques were from southern Mozambique, and as interviews with residents have borne out, many originating from the immediate vicinity of the city sometimes looked with condescension on “newcomers” from other districts, who were often in more desperate situations. African women were largely shut out of waged work, and single women lived in particularly precarious circumstances. Many brewed traditional beer illegally to get by, others resorted to prostitution (Sheldon 2002; Frates 2002). A number of Africans were from the distant north of the colony and the nearby Comoros Islands and shared affinities with the Muslim Swahili culture of the East African coast, while those from the south tended to belong to the Catholic Church or Protestant denominations. Among the most important distinctions to be made, though, the one that for an African in Lourenço Marques was the ultimate determinant of one's place in the colonial-era hierarchy, was that between indígena and assimilado.

Figure 10.3 Population of Lourenço Marques/Maputo, 1940–97.

As with most European colonial regimes, the Portuguese had long cultivated a class of more privileged Africans (Honwana 1988; Penvenne 1989, 1991, 1995). Under the laws that prevailed until the early 1960s, blacks who officially “assimilated” were recognized as Portuguese citizens, with the limited rights that citizenship under a dictatorship conferred, including the right to live in the City of Cement. The path to assimilation was arduous, and few Mozambicans had either the resources or opportunity to attempt it. One had to achieve a certain level of formal education, formal employment, and literacy in Portuguese. After one achieved assimilado status, an official visited one's home to verify that only Portuguese was spoken, that meals were “Portuguese” and eaten with a knife and fork, and that husband and wife both dressed in appropriately Western clothing. The family also had to reside, at minimum, in a decently built wood-framed, zinc-paneled house, rather than a house built of reeds.

Assimilation was a degrading process, predicated on the complete dis-avowal of one's African traditions and values—at least outwardly. It was humiliating, too, that whites didn't also have to prove they were “civilized.”3 And so, though legal assimilation was a virtual requisite for better employment opportunities, there were some Mozambicans with many of the necessary qualifications who refused to go through with it (Penvenne 1995; Castelo 2007). For decades the path to assimilation served as Portuguese proof that its policies did not distinguish by race, since even Africans could become citizens.

In 1960 there were approximately 5,000 assimilados in a colony of about 6 million (Newitt 1995). All other blacks were identified as indígenas (“natives”) and black men were subject to forced labor if not formally employed. The fact that fractionally few blacks met the Portuguese standard reinforced the notion that the essence of blackness was to be uncivilized. Whiteness, meanwhile, was linked to a bundle of practices and experiences—language, cuisine, dress, a specific educational curriculum, occupation—that defined what it meant to be civilized, or evoluído, evolved. And whiteness remained linked to a specific place: the formalized city.

Assimilados were office clerks, printing press typesetters, truck drivers, nurses, and schoolteachers. Though they earned more than black men who unloaded ships at the port, or black men who laundered the clothes for Portuguese families in town, or black women who worked on plantations at the city's edge, their incomes were still very modest by the standards of what most whites earned. In the 1960s, many better-off blacks stood with men of mixed race in the societal pecking order: working in jobs below whites in the civil service or as laborers, and often for a great deal less pay (Penvenne 1995; Castelo 2007). With few exceptions, white Portuguese received preference for job openings (Honwana 1988; Penvenne 1995).

Figure 10.4 Lourenço Marques and its neighborhoods at independence, 1975. Key: 1. Port and rail facilities, Subúrbios (yellow); 2. Chamanculo; 3. Xipamanine; 4. Mafalala; 5. Munhuana; 6. Aeroporto; 7. Maxaquene; 8. Polana Caniço City of Cement (red); 9. Alto Maé; 10. Baixa (downtown); 11. Polana; 12. Sommershield. (Credit: Luciana Justiniani Hees, adapted from a map in Henriques 2008)

The legal division of the black Mozambican population into assimilado and indígena was abolished along with the regime of forced labor in 1961. During the last decade or so of Portuguese rule, as the Lisbon regime battled Frelimo guerillas in northern Mozambique, Portuguese authorities attempted to win over Mozambican “hearts and minds” (Castelo 2007). Educational opportunities for Mozambicans in Lourenço Marques improved, and as wartime development boosted the city's economy, employment prospects improved as well. The numbers of relatively favored black Mozambicans, still commonly referred to as assimilados, grew. But, as Penvenne points out, a wage ceiling remained in place: with the continual swelling of the city's white population, the incomes of assimilados with the highest levels of formal education stagnated (Penvenne 2011).

The city, meanwhile, became perhaps more racially segregated than it had been before. The vast majority of whites lived in the City of Cement. Asians—those not living in the shantytown cantinas they owned—lived mostly in the two commercial neighborhoods within the City of Cement (Mendes 1985). Most people of mixed race as well as the great majority of Africans lived in the shantytowns. The lines were not definite: Hundreds of poor whites lived in the shantytowns and thousands of blacks lived as servants in the backyards of the City of Cement (Castelo 2007). But that the City of Cement was “the white city” was not a matter in dispute for those who actually lived in Lourenço Marques, black or white, in the 1960s and early 1970s (Rita-Ferreira 1967; Honwana 1988; Oliveira 1999; Frates 2002; Penvenne 2011). Antoinette Errante argues that racial segregation was part of the “artificial homogenization” of the diverse white population of Lourenço Marques (Errante 2003, 14). Establishing European superiority meant masking the class differences among whites, and this, in turn, meant rescuing poor, often illiterate Portuguese from comparison with Africans.

Segregation in Lourenço Marques was not achieved through overtly racial laws (Frates 2002). The city wasn't governed by anything similar to the ruthless legal apparatus of apartheid South Africa, which eliminated “black spots” in areas officially designated for white habitation. Rather, early dislocations of blacks from the city to the shantytowns were largely effected through the passage of new building codes, which outlawed the construction of lower-quality housing within city limits (Rita-Ferreira 1967; Frates 2002). Thereafter the racialized job market ensured that even better paid assimilados usually couldn't afford to build or rent a home in the city, and the reforms of the 1960s which opened up more opportunities for Africans did not at the same time open the doors to the City of Cement (Penvenne 2011). The few blacks with sufficient means were often blocked by the simple racism of landlords (or assumed they would be). Against such bigotry, ever more rigid with the continuing influx of white immigrants, there was no real recourse (Castelo 2007; Penvenne 2011).

In many respects, Portuguese colonial urbanism mirrored cities elsewhere on the continent. Whether ruled by France, Britain, Belgium, fascist Italy, or Portugal, cities in colonial Africa were usually organized on the basis of racial classification (Abu-Lughod 1980; Winters 1982; Prochaska 1990; Wright 1991; Çelik 1997; Myers 2003; Coquery-Vidrovitch 2005; Fuller 2007; Njoh 2008; Myers 2011). The logic of colonialism, like its apartheid variant, demanded separation of the races, at least where whites were present in any numbers. Without the notion of a hierarchy of peoples European control lacked a convincing self-justification. Cities maintained this social hierarchy through spatial hierarchy.

A typical settler-colonial city was consciously developed as the embodiment of what modernity and European civilization were said to represent and what African societies might eventually aspire to under European guidance: it was rationally planned, technologically superior, hygienic according to the latest principles of medical science. Until the 1930s, a “sanitation syndrome” guided urban development across the continent. Fear of Africans as vectors of malaria and other disease justified the demolition of African neighborhoods in city centers and the removal of their residents to undeveloped, unserviced, and usually low-lying land beyond the city's edge, often separated by a cordon sanitaire of open space. As if to enhance the contrast, some colonial cities were, architecturally, more deliberately “European” than European cities themselves.

Indigenous populations were to be kept close enough to be of use, while at the same time kept in their place—whether in backyards or the city's margins—and only for as long as their labor was needed. Movement was often strictly controlled. Until the 1960s, for instance, a person classified indígena was only permitted to live in the area of Lourenço Marques— including its shantytowns—if he or she carried an official pass granting that right, a pass predicated on formal employment. Getting caught without a pass could subject the offender to beatings, jail time, forced labor, or in extreme cases, deportation to the cocoa plantations of the island of São Tomé (Penvenne 1983, 1989, 1995; O'Laughlin 2000). The idea of an African city, a city populated mostly by Africans and shaped by the complexities of African life, was contrary to what a city was supposed to be.

The various European colonial powers did not share an identical vision. Some cities in Britain's African empire, notably Nairobi, opted for a standard apartheid-like arrangement (Myers 2003), and the British were in general less circumspect in using race as the criterion for spatial separation. The Portuguese (until the 1960s, at least) shared a great deal of affinity with the French. Like the French, the Portuguese provided some Africans with an avenue to citizenship and equal rights, including the right to live in European districts (Wright 1991; Çelik 1997; Morton 2000). But all these different legalisms were not nearly as significant as the ultimate de facto reality of racial residential segregation which so many white settler cities held in common until independence.

If Portuguese colonial urbanism set itself apart (i.e., apart from all but French Algeria) it was in the sheer size of white settler populations in its cities and the intensity of construction necessary to house them. By the 1960s the streetscape of Lourenço Marques was dominated by high-rise apartment buildings, a glaring contrast with the low-density neighborhoods of bungalows characteristic of white districts in many other African cities. One result was that the City of Cement—particularly images of its modernist architecture—played an unusually large role in giving meaning and content to being white and Portuguese in the Mozambican context (Frates 2002; Penvenne forthcoming). One might say that the City of Cement was built as it was for this very purpose. In any case, it gave the independent government of Mozambique an entrenched built legacy of considerable size to contend with.

The second significant difference pertained to shantytown growth. With greater industrialization and the greater need for African labor, nearly all urban areas in Africa experienced a dramatic increase in African population after World War II (Freund 2007). The growth was even more pronounced in the 1960s, in large part because newly independent governments abolished urban influx controls. In Portuguese cities in Africa, however, influx controls were eased years before independence. Shantytown populations exploded in size for a further generation while still under colonial rule, sharpening the distinction between the booming City of Cement and its booming shantytowns and between the daily lives of whites and the daily lives of blacks.

The Cement City and Its Shantytowns

Lourenço Marques emerged in the late nineteenth century as the principal port city for the goldfields of neighboring South Africa. By World War II, it was one of the busiest ports in Africa, and it soon became one of southern Africa's most populous cities. With ever-increasing Portuguese immigration, it also possessed one of the largest white settler communities south of the Sahara (Duffy 1962; Castelo 2007; Penvenne 2005, 2011). During the last generation or so of colonial rule, Lourenço Marques had the appearance of being two cities: one mostly white and the other mostly black—two distinct urban landscapes, divided for the most part by the curve of Avenida Caldas Xavier (Anon 1974).

The City of Cement was inside the curve, which for a number of years was also the official city limit. Nearly all buildings were built of concrete blocks or clay bricks, cars drove on a grid of paved roads, and homes were hooked up to electricity and running water. The neighborhood of Alto Maé, in the northwest part of the formalized city, was the one area with a notable degree of integration, a part of town where Indians, lower-income whites, people of mixed race, and a small number of blacks lived side-by-side (Mendes 1985; Penvenne 1995; Frates 2002).

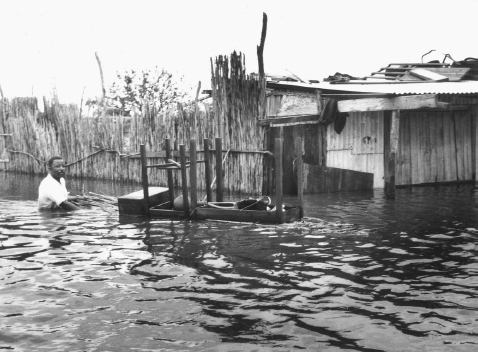

Figure 10.5 Lourenço Marques's City of Cement, 1971. (Credit: F. Sousa/AHM)

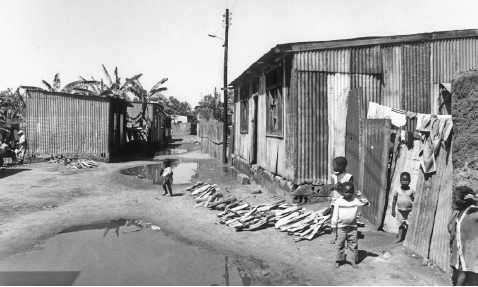

Outside the curve the shantytowns began. The subúrbios, as the shantytowns were often called, existed in the gray area of the law. Housing there was unauthorized, and therefore officially illegal, but it was tolerated (Morais 2001). Most houses were built of reed walls with zinc roofs, roads were mud tracks, homes were lit with paraffin lamps, and fetching water was a daily tribulation. In the absence of sewage and drainage systems, flooding and cholera outbreaks were common and malaria rampant. In the 1960s, the local press dubbed the shantytowns the Cidade de Caniço, the City of Reeds (Rangel 1996).

In the workplace and in bars after work, men from different backgrounds often mixed easily—particularly when the black men were assimilados. In private homes in the city it wasn't unusual for the children of black women to grow up with the children of the women's white employers. This kind of essentially human conviviality persists pretty much anywhere, but while people may have felt close to each other as individuals, they inevitably met on profoundly unequal terms (Errante 2003). In L. Lloys Frates's study (2002) of Mozambican women's memories of late colonial Lourenço Marques, the City of Cement was described as a place where one walked with caution if one went there at all. Assimilados, particularly men, could be seen at restaurants, the cinema, schools, and in shops.

Figure 10.6 The shantytowns of Lourenço Marques were built on poorly drained, flood-prone land that was deemed undesirable for European development. During the annual rainy season, African residents of many neighborhoods lived with standing water in their homes, and malaria and cholera took a heavy toll. This photo was taken in 1966, in the aftermath of the historically catastrophic Tropical Depression Claude. (Credit: AHM)

The beach and government buildings, though, were strictly white places. Mozambican women without shoes or wearing traditional capulana wraps couldn't get on downtown buses or enter stores. “We were not relaxed in the city and we went to work and returned to the suburbs when the work was over,” said Fernas Tembe. “When we walked in the street they did not pay any attention to us, but, for example, the children of Whites provoked us” (Frates 2002, 194–95). In more recent interviews, men described the tension of any encounter with authorities, when forgetting to remove one's cap in respect could result in physical punishment.

One former ranking official, João Pereira Neto, once the intelligence chief for Portugal's Overseas Ministry, recalled in a recent interview that he was shocked by the polarized racial climate that prevailed in Lourenço Marques, which seemed to have more in common with a city in South Africa than it did with its colonial sister city, Luanda. On a visit to Mozambique's capital in 1970 he was astonished by the sight of black workers rushing home to the caniço after work in the City of Cement, hoping to avoid being caught up by an informal nine p.m. curfew. “It wasn't an official curfew,” said Neto, “but they knew that they ran the risk of running into a group of whites, those that the Mozambicans called a ‘posse.’” Mozambique in the 1960s and 1970s functioned as a kind of renegade province, Neto said—a place where local officials and white civilians undermined Lisbon's attempts at reform.

The city's shantytowns were terra incognita for most Portuguese, less known and less well understood than many parts of the Mozambican countryside (Penvenne 2011). Maps of Lourenço Marques rarely showed anything beyond Avenida Caldas Xavier, as if the neighborhoods that sheltered the majority of the urban area's population were nameless, or did not exist (Morais 2001; Frates 2002). These neighborhoods were only a few miles from City Hall, but as one resident recalled, during the war for independence the Portuguese distributed propaganda in the shantytowns by dropping leaflets from helicopters.

The racial division of Lourenço Marques was visibly so stark in part because it was inscribed in the architecture. To build within city limits, one had to use permanent materials—hence the colloquial designation “City of Cement” (Rita-Ferreira 1967). In the shantytowns, however, construction in permanent materials required a builder to jump through so many costly regulatory hoops that it was effectively prohibited. The shantytowns were areas zoned for prospective expansion of the formal European city; concrete houses there would have made the work of bulldozers more difficult (Morais 2001).

But because the differentiation of African society was contained within the confines of the shantytowns, they were nonetheless places of great diversity in construction. Residents interviewed about the housing choices they made in the colonial era described what was essentially a three-tiered shantytown society.4 The most destitute residents, often recent arrivals from the countryside, rented single-room units in cramped compounds. Many people shared the same room, and perhaps dozens of people would share the same latrine and, if one was available, a single water spigot. In the 1960s, rent for a single-room unit might run from 20 to 50 escudos a month.

Those with steadier employment and greater means generally lived in a one- or two-roomed reed shack built with their own hands. Many also rented such units, paying perhaps 150 escudos per month.

And in the older, more established neighborhoods, such as Chamanculo, Xipamanine, and Mafalala, half the homes or more were wood-framed, zinc-paneled houses. Some of these were featureless shacks, not much of a step up from the reed version. The grander examples, the homes of the shantytown elite, featured multiple-pitched roofs with high gables and covered verandahs and wood floors and large pigeon coops, all of which spoke eloquently of the relative wealth and taste of its owner. Some people clandestinely built concrete walls behind the zinc panels. These finer houses, when rented out, might go for 500 escudos a month.

Figure 10.7 Zinc-paneled houses in the Maputo Neighborhood of Minkadjuine, 1987. (Credit: CDFF)

The disparities within the caniço were in some ways as striking as those that distinguished the caniço from the City of Cement. A kind of proto-middle class emerged: assimilados and mestiços who spoke fluent Portuguese, who in the workplace formed relationships with white Portuguese that exceeded the typically narrow dynamic of servant and patrão, and for whom the formalized city—predominately white though it might be—was, if not completely welcoming, at least not completely foreign. Stifled by the racial barriers of Lourenço Marques, this shantytown elite was, following independence, poised to enter Maputo with confidence.

The experience of personal racial humiliation in Lourenço Marques influenced many early policy decisions by Frelimo (Hall and Young 1997). Many leaders of the new government, including President Samora Machel, had themselves been assimilados, had been promised equality by the Portuguese in principle, and then denied it in practice. During Machel's 1976 speech announcing the nationalization of rental housing, he recalled for his audiences the apartheid structure of the colonial capital. Nationalization—which appropriated for the government not just abandoned properties around the country, but all rental housing in Mozambique's various Cities of Cement—would be an important victory over the legacy of colonialism, as it would end capitalist speculation and abolish racial and social discrimination in housing. The apartment buildings of the city were “built on top of our bones, and the cement, sand, and water in those buildings is none other than the blood of the workers, the sweat of the workers, the blood of the Mozambican people! Buildings are the highest forms of exploitation of our people” (Machel 1976, 60).

Figure 10.8 Mozambique's President Samora Machel addresses a Maputo crowd, 1980. (Credit: Martinho Fernando/CDFF)

As Machel ended his speech, he issued a caveat. The president warned that not everyone who wanted an apartment or a house in the City of Cement would get one. Only those who made a reasonable income, he said, would be able to afford to live in a nationalized building. The buildings were state assets. The loans that had financed their construction somehow had to be paid off. Although rents were dramatically reduced from what they had been previously, the nationalization of rental buildings was still geared toward those who could recoup the government's investment and best maintain the physical condition of the colonial inheritance.

Much of the best vacant property was spoken for. Most of the posh districts, such as Polana and Sommerschield, were quickly occupied by Frelimo officials and various state institutions, or reserved for foreign diplomats and the many foreigners, Frelimo sympathizers, who arrived in Maputo to volunteer their skills to the socialist cause (Mendes 1989; Sidaway and Power 1995). Thousands of former Frelimo guerillas and their families were offered apartments in the rest of the city, as were the victims of flooding earlier in the year. Officials of APIE, the state agency created to manage the newly nationalized properties, became notorious for helping themselves, illegally, to many of the best units (Zunguza 1984).

The rental policy was soon made more equitable, with rent pegged to income. Families earning less were charged less than higher income families, no matter where in the City of Cement they were housed (Jenkins 1990). Yet, the formerly European core remained privileged territory (Mendes 1989). By 1980, only about 8 percent of the houses and apartments of the country's Cities of Cement were occupied by people who were officially categorized as “working class” (Carrilho 1987). The majority of units in formalized urban areas were occupied by people in the services sector (and the majority of these were government workers) the relatively few who earned a decent wage in the postcolonial order.5

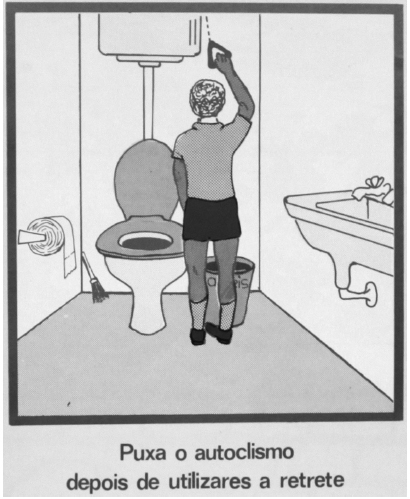

As residents of the city recalled in interviews, rent wasn't the only cost to living in Maputo's City of Cement. One also had to factor in the costs of electricity and water. To cook the meals most people were accustomed to—and that they could afford—they would need their large mortars and pestles to make corn meal. But you were prohibited from bringing them into apartments because thousands of people pounding corn cobs on verandahs would compromise the structure of buildings. Nor could one use a coal-burning stove.

People like Sebastião Chithombe never even considered a move to the City of Cement. By 1976, he was living in the shabby backroom of a shanty town cantina he had purchased at a deep discount from a departing Portuguese the year before. His friends in the compounds were laborers, and not able to afford the rent in the city. There was some reluctance to make that move, even among those with greater means, people generally from assimilado backgrounds for whom such a move was potentially possible. Helena Macuacua, a young teacher living in the Aeroporto neighborhood, thought it was too risky. “I couldn't put the money together for it,” she said in a recent interview. “I saw the rent was going to be very high, and also my husband wasn't someone I could trust. I preferred to plant myself here where things were accessible rather than go to the city and afterward suffer the consequences.” Benjamim Benfica, another schoolteacher, lived in a zinc-paneled house in Chamanculo that his father, a truck driver, had built. He chose to honor his late father's wish that he never give up the house. “We didn't have electricity, we didn't have a sewage system, but it was my house. This is the fundamental part.”

Benfica was young for a homeowner, only twenty-one at independence. Many of his friends, and many of Helena Macuacua's friends, jumped at the chance to live in the City of Cement—though many also returned to the subúrbios within a few years when costs proved too much to bear. (It was not unusual for people who had ventured a life in the City of Cement to return after a month or two.) Many others, like Benfica's father, had spent their adult lives saving up to build a house of their own in the shantytowns, and some families had lived on the same plot for decades. A house was the one solid investment that one could pass on to successive generations. For many people of this older generation, the City of Cement had been so distant and the lifestyle it required so unattainable that living there never took shape as an aspiration. A common anxiety that cropped up in interviews, far from unreasonable, was that the government would not survive and that the old order would return. Given that the new housing rules dictated that a family could only have one house,6 the situation was too uncertain to exchange the home one had for a home one had not even hoped for.

For all the drama accompanying the nationalization of rental housing in the City of Cement, the real impact for most shantytown dwellers was the policy's consequences for shantytown housing. In some neighborhoods of the caniço, as much as 70 percent of the housing units were rentals (Rita-Ferreira 1967). According to a recent interview with former housing minister Júlio Carrilho, the nationalizations were never intended to apply to the shantytowns. But neighborhood-level activists, inspired by Machel's speech and Frelimo's characterization of rent as “exploitation of man by man,” began “nationalizing” compounds and rental shacks in the subúrbios as well.

This spontaneous, grassroots phenomenon—rare under a government known for its heavy-handed, top-down approach (Hall and Young 1997)— spoke more to the nature of most people's expectations than the reoccupation of the City of Cement did. Shantytown nationalization, as Carrilho later reflected, addressed a long-held and heartfelt desire: it was a demand by shantytown dwellers for a meaningful form of citizenship, one in which the government acknowledged its responsibility for all parts of the city. Within a week of Machel's speech, the government became the reluctant landlord to a good share of the shantytown landscape.7

Frelimo in the first years of its rule regarded the seat of its power with suspicion (Hall and Young 1997; Sidaway and Power 1995). The capital city had been the colonial regime's beating heart—a place where the Portuguese influence had been most direct, and where, after independence, an African “petit bourgeoisie”—assimilados—with their supposedly colonized minds, lurked as a potential internal threat. Machel said he looked forward to the influence on the city of an influx of people from the countryside, who would bring with them their rural, communitarian values, and to putting city dwellers to work in the countryside, where they would learn what it meant to be authentically Mozambican (Machel 1976).

Yet it was this same petit bourgeoisie that was given the keys to the City of Cement. One of the contradictions of Portuguese propaganda had been that even those Africans considered “civilized” were effectively barred from living within the borders of the designated civilized enclave. That contradiction had now been resolved, so that the postindependence dispensation gave a measure of coherence to colonial-era attitudes linked to race—attitudes that distinguished between “civilized” and “uncivilized” ways of life, between the fixed city dweller and the rural sojourner who was best suited to the shantytowns.

Frelimo was itself marked by contradiction. For all its championing of traditional rural values, Frelimo also demonstrated a distaste—in word and in practice—for what it regarded as country backwardness, and Frelimo leaders considered themselves the clear-eyed agents of modernization (Hall and Young 1997; Pitcher 2002; Mahoney 2003; Sumich 2005). Perhaps populating central Maputo with civil servants was another example of how its ideas of what constituted modernity—and the modern city—echoed Portuguese notions (and not just Portuguese notions, of course). While listing the do's and don'ts of making a home in the City of Cement—such as not bringing livestock into buildings—the president instructed future tenants to not hang their colorful capulanas outside their apartments. “Otherwise the city will look as if it belongs to monhés,” a common, though pejorative term for Indian and Arab Muslims (Machel 1976, 69).

Figure 10.9 Following independence, apartment living was unfamiliar and uncomfortable for many of the new occupants of the City of Cement, where many accustomed practices were prohibited, such as cooking on open coals, pounding cornmeal, and keeping chickens and goats. Pictured is a detail from an undated poster demonstrating the proper use of fl ush toilets, distributed by Mozambique's Health Ministry. (Credit: Ministério de Saude/DNMP)

But continuities with colonial-era mentalities can be overstated. The practical reasons to favor more privileged Mozambicans in the distribution of City of Cement housing were obvious: the City of Cement would likely fall apart otherwise. Given the limited number of apartments relative to the urban population, occupation of the City of Cement was never going to be more than a partial solution to Maputo's housing problems in any case (Jenkins 1990). And much was beyond Frelimo's ability to control. There was little the government could do, after lowering rents, to make apartment living affordable, or for that matter, livable.

It should be noted that the new tenants of the City of Cement were not all the so-called petit bourgeoisie. Many new residents (it is difficult to estimate how many) had come directly from the countryside, such as the many families of ex-guerillas. Or they were among the poorer households from the shantytowns, such as those evacuated from flooded neighborhoods. For them, the City of Cement was an uncomfortable fit. Despite prohibitions, many of these residents continued with their daily routines: cooking on open coals, raising goats and chickens in their apartments, and pounding grain on their verandahs. Common spaces of buildings became trash dumps (Anon. 1981). Journalists played up stories of simple Mozambicans baffled by the use of bathtubs and flushing toilets, and children who relieved themselves everywhere except where they were supposed to (Manuel 1985). Housing officials despaired of the threat to public health, and the damage to what they considered the nation's patrimony.

The building stock of the City of Cement was indeed deteriorating, and at a rapid pace (Jenkins 1990, 2011). It wasn't just the pounding of cornmeal contributing to the physical decline. The generalized collapse of the Mozambican economy following the Portuguese withdrawal resulted in dire shortages, including shortages of building materials. In Maputo, nails and cement mix and tools became scarce items (Tembe 1987). At the same time, when coal or cooking gas was short (which was often) cooking fires were often fueled by the wood of parquet floors (Ribas 1983).

And conditions continued to worsen. The decade of the 1980s was among the most trying in Mozambique's modern history. Apartheid South Africa bankrolled an anti-Frelimo insurgency, called Renamo, fueling a catastrophic war. Hundreds of thousands fled from the countryside to Maputo, seeking protection from the violence. The population of the city roughly doubled between 1980 and 1997 (Henriques 2008) and the capital and its shantytowns took on the character of a crowded refugee camp. Overwhelmed by the influx, Frelimo embarked in 1983 on a draconian program to purge Maputo of “unproductive elements”—people who could not prove they had formal employment. Tens of thousands of people lacking the proper documentation and who could not return to the rural homes from which many had fled were “evacuated” to remote provinces to work on state farms (Castanheira 1983a; 1983b; 1983c; Naroromele 1983).

By 1987, the Frelimo government, brought to its knees by war, drought, and economic hardship, gave up its socialist program, and adopted the market reforms imposed by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank (Pitcher 2002). At the end of that year, the rent structure was adjusted to more closely reflect perceived market demand (Carrilho 1987). Rents, on average, more than doubled over the next five years (Sidaway and Power 1995). For many who had managed to endure in the City of Cement for a decade, the rent hike was the last straw, and it forced a move to the shantytowns (Mendes 1989).

Those who were able somehow to hang on during the brutal winnowing of Maputo were able to profit handsomely. In the 1990s, the government started selling rental properties to their occupants, and tenants, in turn, either sold or rented their apartments (Jenkins 2011). It was a seller's market, with home prices and rents boosted by the foreigners who came with the dizzying array of United Nations agencies and nongovernmental organizations that descended on Maputo, many after the end of the war with Renamo in 1992 (Hanlon 1997). Until then, living in the City of Cement had been a dubious luxury. Now, with an apartment an increasingly valuable asset to leverage, a relatively privileged group of city dwellers became even more privileged, and the social gap between themselves and those who lived in other parts of the city widened. For some an apartment became the primary source of income; some used the profits from selling an apartment, or the income from renting one out, to build a concrete-block house in the subúrbios or the city's distant and spacious exurbs (Jenkins 2011). The City of Cement didn't just house the African middle class. A generation after independence it also brought the middle class fully into being.

Theoretical Considerations: Transformations from a Racial System to a Class System

What can critical geographers and Marxist sociologists learn from the nationalization of housing in Maputo's City of Cement? The quick transformation after independence from a city divided principally by race to a city divided principally by class was not remarkable in itself: it was the common experience in cities throughout the decolonized world. African and Asian elites moved into neighborhoods built to house European elites (Coquery-Vidrovitch 2005). In most colonial cities, white districts were not particularly large, and their occupation by ruling parties amounted to little more than a changing of the guard. But in Maputo, after the new regime occupied the choicest real estate, much of the extensive City of Cement still remained to be parceled out. And as it distributed these properties, Frelimo favored an already favored class of people who in speeches it vilified as potential counterrevolutionaries.

Perhaps this decision reflected an inveterate modernizing impulse, one evident in so many state interventions after independence. Perhaps Frelimo envisioned a “modern” city as an essentially European one in its order, appearance, and stratification. If so, Frelimo's policy was an only slightly modified recapitulation of attitudes that shaped the city in the past, and those Mozambicans called assimilados were the natural inheritors of the “civilized” part of the city. Another, more important factor, however, was at work: Concrete. On the one hand, the buildings of the City of Cement weren't going anywhere. On the other hand, the buildings were subject to falling apart if not properly maintained, requiring an investment in the buildings themselves, in the almost 900 building superintendents to look after them, and in the bulky bureaucracy required to manage it all. To foot this bill, Frelimo was compelled to preserve the kind of economic and social segmentation that in other areas—such as public health and education—it refused to do. There is more to consider, furthermore, than Frelimo policy. Even for many people earning steady wages, life in a low-rent apartment, and even a rent-free apartment, proved considerably harder than life in the subúrbios. Inequality was seemingly hardwired into the city's structure.

One of the lessons to be learned from the case of Maputo (or rather, learned again) is the significance of the relative durability of urbanism itself: how a built legacy can convey the values of the past into the present, long after planners and builders are gone from the scene. Much of the work on colonial-era architecture and urbanism in Africa begins with Foucault as a starting point (whether he is acknowledged or not) with an emphasis on the intentions of colonial administrators and architects—the ideologies they brought to the drawing board, and that were embedded in the finished product (Wright 1991; Çelik 1997; Fuller 2007). As the work of Garth Myers (2003) suggests, one needs to examine, too, how people actually lived in colonial-era built environments over time, and reconfigured them to their own needs. His approach shares something of the spirit of Michel de Certeau (1984): ordinary people aren't the hapless victims of the spatial structures of control as Foucault makes them out to be.8 The insight is an intuitively satisfying one, but in Maputo's City of Cement it finds an empirical test: there, even the new regime could not make the built landscape conform to new priorities; demolition, let alone construction, was a luxury. A converted movie theater served as the young nation's popular assembly.

Ultimately, though, the issue was not that most Mozambicans were ill-suited to the City of Cement, and the living arrangements it presupposed, but rather that the City of Cement was fundamentally unsuitable for Mozambique—a constant reminder of colonialism's colossally bad fit., The center of gravity of African life in Maputo has long been located on the city's margins, whether during the colonial era or afterward. Today, the “shantytown” designation is far less appropriate than it was before. Most houses are built of concrete block, and people from all walks of life live in them. Houses in the subúrbios are still unauthorized for the most part, still officially illegal, but the aspiration of the people who live in these neighborhoods is not to move to an apartment in what was once called the City of Cement. Rather, when most people in Maputo talk about their future, they imagine building a house on a larger plot of land in the peri-urban areas of Matola or Marracuene, even further from downtown, and that much closer to the countryside.

Acknowledgments

This chapter draws upon research that was generously supported by the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, the Fundação Luso-Americana, the University of Minnesota Office of International Programs, and a Fulbright Program grant sponsored by the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the U.S. Department of State and administered by the Institute of International Education.

Glossary

APIE—Acronym for Administração do Parque Imobiliário do Estado, the Mozambican state agency that administered all state-owned real estate following the nationalization of rental buildings in 1976.

Assimilado—During most of the colonial era, one of several thousand black Mozambicans who were considered legal Portuguese citizens. To “assimilate,” an African had to establish that he or she was sufficiently “civilized,” a standard that included reading and writing Portuguese, eating and dressing as a European was said to eat and dress, and achieving a certain level of income and formal education.

Caniço—Portuguese for “reed,” until recent decades the most common building material in Maputo's shantytowns. The band of shantytown settlements around the city was often called the caniço or the Cidade de Caniço (“City of Reeds”).

Cidade de Cimento—“City of Cement.” During the colonial era, the common term for the formalized, largely European part of the city where streets were paved and most buildings were built in concrete or brick.

Frelimo—The Frente da Libertação de Moçambique, or Mozambique Liberation Front, the one-time anticolonial guerilla force that, as a political party, has governed the country since independence. Indígena—Portuguese for “native,” the official classification of the vast majority of Mozambicans for most of the colonial era. Those with indígena status were denied the rights of Portuguese citizenship and subject to terms of forced labor, called chibalo.

Renamo—The Resistência Nacional Moçambicana, or Mozambican National Resistance, an armed insurgency assembled from Frelimo discontents by Rhodesia's white minority (the country became independent as Zimbabwe in 1980), and later backed by apartheid South Africa. From 1976 to 1992 the group sought to disable Frelimo's ability to govern, doing so mostly through attacks on civilian populations. The civil war that resulted—Frelimo calls it a “war of destabilization”—cost the lives of as many as one million Mozambicans and displaced millions more.

Subúrbios—Another, more official term for the Cidade de Caniço, still in common parlance. Unlike the English word suburb, which indicates a lack of urban density, subúrbio indicates a lack of urban infrastructure, such as paved roads, sewage systems, and water provision.

Notes

1. Historian Jeanne Penvenne is the widely recognized authority on colonial-era Maputo, particularly in matters of labor and class, and the rest of this section owes a particularly heavy debt to her work.

2. A number of people of mixed race were also of Indian or Chinese heritage.

3. Some 40 percent of the Portuguese who left Mozambique for Portugal in 1974–75 were illiterate (Errante 2003).

4. Frates (2002) describes a three-tiered society of the city as a whole: black, assimilado, and white.

5. By 1982, most of the country's economy was state-run (Pitcher 2002).

6. A second home was permitted if it was located in the countryside.

7. Nationalization of rental housing should not be confused with nationalization of land. In order to put a halt to speculation, the government has claimed since 1975 the sole right to buy and sell land.

8. See Martin Murray's observations regarding de Certeau and urban squatters in and around Johannesburg (Murray 2008, 106).

References

Abu-Lughod, Janet L. 1980. Rabat: Urban Apartheid in Morocco. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Andrade, António Alberto Banha de. 1961. Many Races–One Nation: Racial Non-Discrimination Always the Cornerstone of Portugal's Overseas Policy. Lisbon: Tip. Silvas.

Anon. 1974. “‘Apartheid’ na habitação” [Apartheid in housing]. Tempo, October 27.

———. 1981. “Janela Aberta” [Open window]. Notícias, January 30.

Bender, Gerald J. 1978. Angola under the Portuguese: The Myth and the Reality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Boxer, C. R. 1963. Race Relations in the Portuguese Colonial Empire, 1415–1825. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

———. 1973. The Portuguese Seaborne Empire, 1415–1825. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Cairo, Heriberto. 2006. “‘Portugal Is Not a Small Country’: Maps and Propaganda in the Salazar Regime.” Geopolitics 11 (3): 367–95.

Carrilho, Júlio. 1987. “Ajustar as rendas ao valor das casas” [Adjusting rents to the value of the houses]. Tempo, October 4.

Castanheira, Narciso. 1983a. “Operação Produção: punir os desvios” [Production Operation: punish deviations]. Tempo, July 24.

———. 1983b. “Operação Produção: de casa em casa” [Production operation: From house to house]. Tempo, August 14.

———. 1983c. “Operação Produção: até onde é que devemos intervir?” [Production operation: How far should we intervene?]. Tempo, August 28.

Castelo, Cláudia. 2001. O modo portuguê s de estar no mundo: o luso-tropicalismo e a ideologia colonial portuguesa (1933–1961) [The Portuguese way of being in the world: The Luso-tropical colonial ideology]. Porto: Afrontamento.

———. 2007. Passagens para África: o povoamento de Angola e Moçambique com naturais da metrópole (1920–1974) [Flights to Africa: the population of Angola and Mozambique with natural metropolis]. Porto: Edições Afrontamento.

Çelik, Zeynep. 1997. Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations: Algiers under French Rule. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Certeau, Michel de. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life, translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine. 2005. “Residential Segregation in African Cities.” In Urbanization and African Cultures, edited by Steven J. Salm and Toyin Falola, 343–56. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

Cross, Michael. 1987. “The Political Economy of Colonial Education: Mozambique, 1930–1975.” Comparative Education Review, 31 (4): 550–69.

Direcção Provincial dos Serviços de Estatística Geral. 1960. III Recenseamento geral da população na Província de Lourenço Marques. [III Population census in the province of Lourenço Marques]. Lourenço Marques: Author.

Duffy, James. 1962. Portugal in Africa. Baltimore: Penguin.

Errante, Antoinette. 2003. “White Skin, Many Masks: Colonial Schooling, Race, and National Consciousness among White Settler Children in Mozambique, 1934–1974.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 36 (1): 7–33.

Foucault, Michel. 1980. Power/Knowledge. Brighton, UK: Harvester Press.

Frates, L. Lloys. 2002. “Memory of Place, the Place of Memory: Women's Narrations of Late Colonial Lourenço Marques, Mozambique.” PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles.

Freund, Bill. 2007. The African City: A History. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Freyre, Gilberto. 1961. Portuguese Integration in the Tropics. Lisbon: Tip. Silvas.

Fuller, Mia. 2007. Moderns Abroad: Architecture, Cities and Italian Imperialism. London: Routledge.

Garenne, Michel, Rudi Coninx, and Chantal Dupuy. 1996. “Direct and Indirect Estimates of Mortality Changes: A Case Study in Mozambique.” In Demographic Evaluation of Health Programmes: Conference Proceedings, edited by Myriam Khlat, 53–63. Paris: Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography (CICRED).

Godinho, António Maria. 1962. O ultramar português: uma comunidade multiracial [The Portuguese overseas: A multiracial community]. Lisbon: Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, Semana do Ultramar.

Greger, Otto. 1990. “Angola.” In Housing Policies in the Socialist Third World, edited by Kosta Mathéy, 129–45. Munich: Profil.

Hall, Margaret, and Tom Young. 1997. Confronting Leviathan: Mozambique Since Independence. Athens: Ohio University Press.

Hanlon, Joseph. 1997. “Mozambique: Under New Management.” Soundings (7): 184–94.

Henriques, Cristina Delgado. 2008. Maputo: cinco décadas de mudança territorial [Maputo: Five decades of territorial change]. Lisbon: IPAD.

Honwana, Raúl Bernardo Manuel. 1988. The Life History of Raúl Honwana: An Inside View of Mozambique from Colonialism to Independence, 1905–1975, edited by Allen F. Isaacman, translated by Tamara L. Bender. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Isaacman, Allen F. 1996. Cotton Is the Mother of Poverty: Peasants, Work, and Rural Struggle in Colonial Mozambique, 1938–1961. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

———. Barbara Isaacman. 1983. Mozambique: From Colonialism to Revolution, 1900–1982. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Jenkins, Paul. 1990. “Mozambique.” In Housing Policies in the Socialist Third World, edited by Kosta Mathéy, 147–79. Munich: Profil.

———. 2011. “Maputo and Luanda.” In Capital Cities in Africa: Power and Powerlessness, edited by Simon Bekker and Göran Therborn, 141–66. Johannesburg, SA: HSRC Press.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Lesbet, Djaffar. 1990. “Algeria.” In Housing Policies in the Socialist Third World, edited by Kosta Mathéy, 249–73. Munich: Profil.

Machel, Samora. 1976. “Independência implica benefícios para as massas exploradas” [Independence implies benefits for the exploited masses]. Speech Given February 3, 1976. In A nossa luta é uma revolução [Our struggle is our revolution]. 33–70. Lisbon: CIDA-C.

Mahoney, Michael. 2003. “Estado Novo, Homem Novo [New State, New Man]: Colonial and Anti-Colonial Development Ideologies in Mozambique, 1930–1977.” In Staging Growth: Modernization, Development, and the Global Cold War, edited by David C. Engerman, Nils Gilman, Mark H. Haefele, and Michael E. Latham, 142–175. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Manuel, Fernando. 1985. “Habitação não é só a casa.” [Housing is not only the house]. Tempo, April 7.

Medeiros, Eduardo. 1989. “L’évolution démographique de la ville de Lourenço-Marques (1894–1975). “[Demographic evolution in the city of Lourenço-Marques]. In Bourgs et villes en afrique lusophone [Market towns and cities of lusophone Africa], edited by Michel Cahen, 63–73. Paris: Editions L'Harmattan.

Mendes, Maria Clara. 1985. Maputo antes da Independência: geografia de uma cidade [Maputo before Independence: Geography of a colonial city], vol. 68. Memórias do Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical 2) [Archives of the Institute of Tropical Research, 2]. Lisbon: IICT.

———. 1989. “Les répercussions de l'indépendance sur la ville de Maputo” [The repercussions of independence on the city of Maputo]. In Bourgs et villes en afrique lusophone [Market towns and cities in lusophone Africa], edited by Michel Cahen, 281–96. Paris: Editions L'Harmattan.

Morais, João Sousa. 2001. Maputo: património da estrutura e forma urbana, topologia do lugar [Maputo: Its heritage and the urban form of the structure, topology of the place]. Lisbon: Livros Horizonte.

Morton, Patricia A. 2000. Hybrid Modernities: Architecture and Representation at the 1931 Colonial Exposition, Paris. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Munslow, Barry. 1983. Mozambique: The Revolution and Its Origins. London: Longman.

Murray, Martin J. 2008. Taming the Disorderly City: The Spatial Landscape of Johannesburg after Apartheid. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Myers, Garth A. 2003. Verandahs of Power: Colonialism and Space in Urban Africa. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

———. 2011. African Cities: Alternate Visions of Urban Theory and Practice. London: Zed Books.

Naroromele, Albano. 1983. “Operação Produção: uma missão histórica” [Operation Production: a historical mission]. Tempo, August 14.

Newitt, Malyn. 1995. A History of Mozambique. London: Hurst.

Njoh, A. J. 2008. “Colonial Philosophies, Urban Space, and Racial Segregation in British and French Colonial Africa.” Journal of Black Studies 38 (4): 579–99.

O'Laughlin, Bridget. 2000. “Class and the Customary: The Ambiguous Legacy of the Indigenato in Mozambique.” African Affairs 99 (394): 5–42.

Oliveira, Isabella. 1999. M. & U., Companhia Ilimitada [M & U, an unlimited company]. Porto: Edições Afrontamento.

Penvenne, Jeanne. 1983. “‘Here We All Walked with Fear’ The Mozambican Labor System and the Workers of Lourenço Marques, 1945–1962.” In Struggle for the City: Migrant Labor, Capital, and the State in Urban Africa, edited by Frederick Cooper, 131–66. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

———. 1989. “‘We Are All Portuguese!’ Challenging the Political Economy of Assimilation: Lourenço Marques, 1870–1933.” In The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa, edited by Leroy Vail, 255–88. London: Currey.

———. 1991. Principles and Passion: Capturing the Legacy of João dos Santos Albasini. Boston: African Studies Center, Boston University.

———. 1995. African Workers and Colonial Racism: Mozambican Strategies and Struggles in Lourenço Marques, 1877–1962. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

———. 2005. “Settling Against the Tide: The Layered Contradictions of Twentieth-Century Portuguese Settlement in Mozambique.” In Settler Colonialism in the Twentieth Century: Projects, Practices, Legacies, edited by Caroline Elkins and Susan Pedersen, 79–94. New York: Taylor & Francis.

———. 2011. “Two Tales of a City: Lourenço Marques, 1945–1975.” Portuguese Studies Review 19 (1–2): 249–69.

———. Forthcoming. “Fotografando Lourenç o Marques: a cidade e os seus habitantes de 1960 a 1975” [Photographing Lourenço Marques: The city and its inhabitants from 1960 to 1975]. In Os outros da colonizaç ã o: ensaios sobre tardo-colonialismo em Moç ambique [The Others of colonization: Essays on late-colonialism in Mozambique], edited by Cláudia Castelo, Omar Ribeiro Tomaz, Sebastião Nascimento, and Teresa Cruz e Silva. Lisbon: Imprensa de Ciê ncias Sociais.

Pereira Bastos, Susana. 2005. “Indian Transnationalisms in Colonial and Postcolonial Mozambique.” Stichproben: Wiener Zeitschrift fü r Kritische Afrikastudien 8: 277–306.

Pinsky, Barry. 1985. “Territorial Dilemmas: Changing Urban Life.” In A Difficult Road: The Transition to Socialism in Mozambique, edited by John S. Saul, 279–315. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Pitcher, M. Anne. 2002. Transforming Mozambique: The Politics of Privatization, 1975–2000. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Prochaska, David. 1990. Making Algeria French: Colonialism in Bône, 1870–1920. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Rangel, Ricardo. 1996. “Os primeiros passos de um fotojornalista famoso” [The first steps of a famous photojournalist]. In 140 anos de imprensa em Moçambique [140 years of press in Mozambique], edited by Fátima Ribeiro and António Sopa, 121–123. Maputo: Associação Moçambicana da Língua Portuguesa.

Ribas, Filipe. 1983. “Não há gás, não há carvão, não há lenha” [No gas, no coal, no firewood]. Tempo, November 20.

Rita-Ferreira, António. 1967. “Os africanos de Lourenço Marques” [The Africans in Lourenço Marques]. Memórias do Instituto Científica de Moçambique [Archives of the Institute of Science of Mozambique] 9 (C): 95–491.

———. 1988. “Moçambique post-25 de Abril: causas do êxodo da população de origem europeia e asiática” [Mozambique following April 25: Reasons for the exodus of the European and Asiatic population]. In Moçambique: cultura e história de um país [Mozambique: Culture and history of a country], 119–169. (Publicações do Centro de Estudos Africanos No. 8. [Publication of the Center for African Studies]). Coimbra: Universidade de Coimbra.

Serviços de Centralização e Coordinação de Informações de Moçambique. 1973. Moçambique na actualidade [Mozambique today]. Lourenço Marques: Author.

Sheldon, Kathleen. 2002. Pounders of Grain: A History of Women, Work, and Politics in Mozambique. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Sidaway, J. D., and M. Power. 1995. “Socio-spatial Transformations in the ‘Postsocialist’ Periphery: The Case of Maputo, Mozambique.” Environment and Planning A 27 (9): 1463–91.

Sumich, Jason Michael. “Elites and Modernity in Mozambique.” PhD diss., London School of Economics, 2005.

Tembe, Alfredo. 1987. “Materiais de construção: quem não tem divisas fica ‘a ver navios’” [Building materials: who has no foreign currency is “dust”]. Tempo, September 20.

Vail, Leroy, and Landeg White. 1980. Capitalism and Colonialism in Mozambique: A Study of Quelimane District. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Winters, Christopher. 1982. “Urban Morphogenesis in Francophone Black Africa.” Geographical Review 72 (2): 139–54.

Wright, Gwendolyn. 1991. The Politics of Design in French Colonial Urbanism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zunguza, Rui. 1984. “Doença da APIE: financeira não … de gestão talvez!” [Disease APIE: financial management maybe not …]. Tempo, August 19.