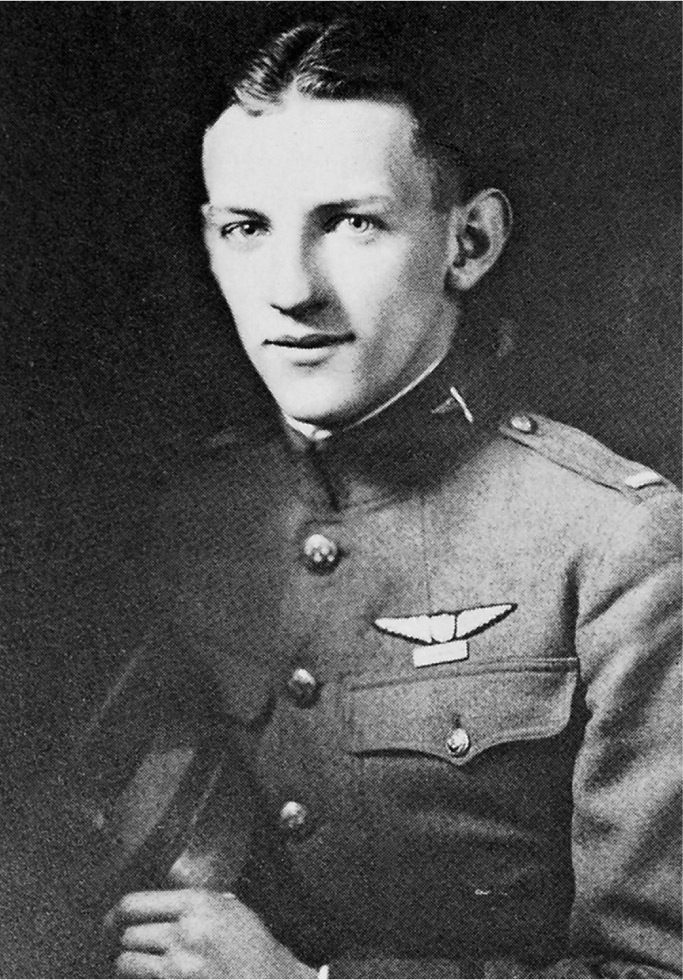

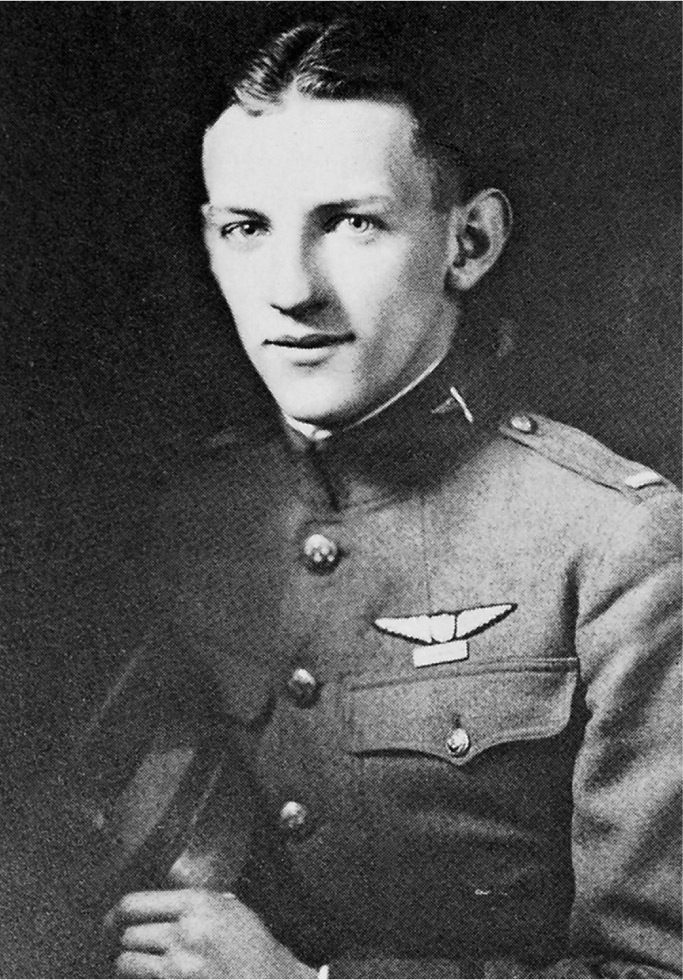

George Vaughn was an ace with thirteen victories who lived to be ninety-two. “All you had to do was fly the plane and shoot the guns,” he said modestly, shortly before his death.

I’m Going to Tell Them I Raised Hell

George Vaughn came from Brooklyn—from the Washington Avenue area, to be exact. Born in May 1897, he enrolled at Princeton University in 1915 and two years later put his name down for the fledging Aviation Corps. “They are organizing here,” Vaughn wrote his parents on February 7, 1917. “But [I] don’t know whether I will be able to get in it or not, as they are going to have examinations for nerves, endurance, etc.”

Vaughn had to wait a couple of months for his medical examination, by which time the Princeton Aviation School had been firmly established and war had been formally declared by Congress. “Committees composed of members of the Faculty and of the undergraduates were formed,” reported the Princeton Bric-a-Brac, the university’s undergraduate yearbook. “Several members of the Faculty volunteered to give lectures on the construction, operation and maintenance of an airplane motor…[and] towards the end of March came the gratifying announcement that sufficient funds had been collected and orders for two airplanes of the Curtiss JN-4B type of military tractor biplane were at once placed with the Curtiss Aeroplane Company.”

Vaughn underwent his physical examination in April, the doctor noting the cadet’s brown hair, blue eyes, and ruddy complexion in his file. Vaughn wrote his family on May 4 to explain that after undergoing the equilibrium and eye test, he had been subjected to a thorough medical “that has put a good many fellows out of the Corps. It was a physical examination such as I never even imagined before, and lasted over two hours and a half. You have to be practically perfect in every part of your body to get by, so I at least have the satisfaction of knowing that I am physically pretty well off.”

George Vaughn was an ace with thirteen victories who lived to be ninety-two. “All you had to do was fly the plane and shoot the guns,” he said modestly, shortly before his death.

Vaughn was one of thirty-six Princeton men out of more than one hundred volunteers who passed the medical, as was Elliott White Springs. “They are very particular about whom they take for the Aviation Corps and examine us very minutely,” Springs had written his father on May 1. “It’s the most exacting examination the Army gives. They spin you around on a stool, make you balance blindfolded, fire pistols behind you and all sorts of things like that.”

Springs confessed to his father that he’d feared his eyes might let him down—“as they only allow a small percentage of variations from normal”—but he passed the medical, unlike Arthur Taber, who failed his. Though an enthusiastic rower and member of the Princeton gun team, the portly young man lacked finesse and aggression. He didn’t lack connections, however, not with so wealthy and influential a father. The dean of the college, Howard McClenahan, wrote to the Aviation Corps to tell them of the student’s “strictest integrity,” while Taber also paid a visit to Washington “and called on a friend…a retired Brigadier-General, whose help in attaining this object he asked.”

At first the RFC resisted the pressure to accept Taber, but, finally, they relented and he was admitted into the Princeton Aviation School in July, by which time Vaughn and Springs and their thirty-four classmates were already accomplished aviators. “I can’t begin to tell you the wonderful fascination of flying and I enjoy it more every time I go up,” Springs wrote his father. “I had control of the plane yesterday for twenty minutes at an altitude of 4,000 feet and I don’t know when I enjoyed anything more.”

The students were taught in the Curtiss JN-4 biplanes on what Vaughn described as “a privately-operated field, located between Princeton and Lawrenceville,” and it was here that Taber joined them, if not trusted to take to the skies, then at least able to participate in “such subjects as theory of flight, internal combustion engines, machine guns, Morse code telegraphy, navigation, etc.” The students, most of whom had hitherto led lives of easy deportment, also encountered military discipline and close order drill for the first time. “All this drill was excessively tiresome and a dreadful bore,” Taber wrote his father on July 26. “…I sometimes regret that I did not join the naval aviation for in that branch now I could make a greater contribution to the Allied cause than where I am.”

Elliot White Springs beams for the camera after walking away unscathed from this flying accident in France.

With the six-week course complete and the cadets now “enlisted as Privates First Class in the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps,” the army faced the problem of what to do with them. “At that time there were no advanced flying schools in this country,” recalled Vaughn. “Fortunately for us, the Allies had started offering the use of their flying training facilities, so the army finally decided to send us abroad for advanced flying training.”

At the end of August the Princeton cadets were sent to Mineola flying field on Long Island, later the site of the Roosevelt Raceway, where they encountered cadets from other flying schools also waiting to embark overseas, some to France and others to Italy.

For Arthur Taber the stay at the Mineola airfield was his first exposure to the rich diversity of his country’s inhabitants. Reared in Lake Forest, Illinois, and schooled in Coconut Grove, Florida, the formative years of Taber’s young life had been spent in a privileged and serene environment. Earnest and studious, Taber entered Princeton, where he was a member of the university’s gun team, which contested an intercollegiate shoot with teams representing Dartmouth, Yale, and Cornell. This was the circle in which Taber felt comfortable: among the wealthy and well-educated, among America’s elite.

On August 28, his first evening at Mineola, Taber wrote his father, explaining: “This seems to be a concentration point for the men who are going to Italy: today a batch came in from Cornell. They are a clean-cut, military-looking lot, and I am rather heartened by their appearance. They are surely exceptional in being trim in appearance, for the average is very low, I regret to say.”

Taber had no issue with the Cornell men, nor with fellow Princetonians such as George Vaughn, Frank Dixon, Harold Bulkley, and Elliott Springs, even if Springs did have something of a wild reputation. At Princeton, he had spent much of his time striking a pose in his Stutz Bearcat, even driving the vehicle to Long Island when they were ordered to Mineola.

However, at least Springs—the son of a wealthy cotton-mill owner from South Carolina—had breeding. Taber wasn’t so sure of some of Springs’s acquaintances, budding aviators who had been ordered to Mineola from other flying schools across America. Clayton Knight, a native of Rochester, New York, and, at twenty-six, one of the oldest men at Mineola, was an artist who had studied under the iconoclastic modernist painter Robert Henri before enlisting in the military in 1917 and being sent to aviation school in Texas.

But if Knight was tainted by association in the eyes of Taber, John McGavock Grider was tainted, period. Born in 1892 at the family cotton plantation in Sans Souci, Arkansas, Grider—or “Mac” as he preferred to be called—had quit the Memphis University School aged seventeen to marry a fellow student, Miss Marguerite Samuels. To escape the scandal, Grider and his young bride retreated to the plantation, where she soon gave birth to two sons, John McGavock and George William. Neither Grider nor his wife adapted well to parenthood; he was working all hours on the plantation, and she found the responsibility too much to bear. The couple separated, Marguerite returning to her family in Memphis with the children, Grider throwing himself into his work. But he was still young and restless, and America’s entry into the Great War was the excuse he needed to flee Arkansas. Writing his family of his decision to enlist, he said: “Do you think I’m going to tell John and George when they get to be men that I raised cotton and corn during the war? Not by a damned sight, I’m going to tell them I raised hell.”

One of the “Three Musketeers,” Laurence Callahan was not just a brilliant ragtime pianist but also an ace with 85 Squadron and 148th Aero.

Grider was sent to the School of Military Aeronautics of the University of Illinois for aviation training, during which he wrote a friend back home of his first flight. “I have been up. God it is wonderful! I have never experienced anything like it in my life.”

Grider’s roommate was Larry Callahan, a tall, laid-back twenty-three-year-old from Kentucky who had curtailed a career in finance to serve his country. The pair hit it off straight away. Callahan was a gifted pianist and Grider loved to dance, the foxtrot being his favorite. They also shared a passion for liquor, women, and cards. Such pastimes were not the preserve of Taber. “I am not a prude about the question of drinking,” he wrote his father, “but I don’t like to see men take too much, first, because of the dire result of their actions upon themselves, and secondly, because someone else is sure to suffer, for some regrettable thing never fails to occur when one is temporarily and abnormally excited.”

Grider and Callahan were separated upon arrival at Mineola. Grider, like Taber, had volunteered for active service in Italy, while Callahan had been assigned to the contingent headed to France. The Italian detachment had as its cadet sergeant Elliott Springs, confident and strong willed despite having just turned twenty-one. A natural leader and a superb aviator, Springs was invested with the limited authority by the officer in charge, Maj. Leslie MacDill, with instructions to ensure the men did nothing to discredit America in the eyes of the watching world.

It was an onerous task for Springs, an exuberant and forceful personality whose character had been shaped in a large part by his prickly relationship with his domineering father. “I am opposed to your joining the aviation corps,” Leroy Springs had written his son in April 1917. “I do not feel that I should give my consent to it.” Aviation was the younger Springs’s escape from parental control, a joy he described in a letter to his stepmother as “the nearest thing to the Balm of Gilead I know.”

But there were other balms in Springs’s life: the same pleasures enjoyed by Grider. At Mineola, Grider discovered that Springs played bridge and liked music, so he told him, “I have a friend over here at this other place that’s a good bridge player and plays the piano. You better get him over here.” The friend in question was Callahan. Springs did as requested, arranging the transfer of Callahan to the Italian detachment of aviators. The three young men complemented each other: the blond, handsome Grider, the eldest of the three but with an infectious boyish enthusiasm for life; Springs, who looked like a boy, his face unmarked by toil or trauma, but whose personality was more complex than either Grider’s or Callahan’s; and Callahan, who asked himself fewer questions than his two friends and just got on with life, taking its vagaries in his languid stride. Before long the trio were calling themselves “the Three Musketeers.”

A reporter from the New York Times ventured to Mineola to spend several days in the company of the cadets and captured the tedium felt by many of the raw recruits in an article entitled “Long, Weary Waiting for Airplane Student.” “The first sight of the high board inclosure [sic] of the flying field brings a distinct thrill,” wrote the correspondent. “But after sitting in barracks day after day, fingering brand-new equipment, cleaning brand-new pistols, hearing the airplanes of the fortunate buzz by overhead, ever and again sneezing in the plentiful dust—that yellow Long Island dust which rises so thickly when the ground is scratched that even the general’s car must slow down on the high road—well, that thrill wears off.”6

As for the cadets who sat listlessly in the classroom, desperate to fly but damned to spend hour after hour studying theory, the reporter from the New York Times sympathized with their plight, writing: “The men who have volunteered for training in Italy are in a curious state of mind. They have no idea of where they are going or of what is going to happen to them when they get there; but they are perfectly sure that it will be the best possible. No one has been sent to Italy for flying training yet, or at least no one has been there long enough to send back word what it is like, and these men will be the first in that particular field, pioneers, explorers. And that is enough.”

On Sunday, September 16, 1917, Major MacDill ordered Springs to tell “everyone to get rid of their cars” except for Springs himself and to “place sentinels around the barracks to keep anyone from leaving even for a few moments.” MacDill and Springs then drove into New York to “arrange the final details” of their embarkation for Europe, and the following day, September 17, Springs deposited his treasured Stutz at the Blue Sprocket garage with instructions for it to be returned to the manufacturer. Springs then drew some money, dined out at a fashionable restaurant, and returned to Mineola at 2:00 a.m. “to find special orders waiting on me to have breakfast at 4:30 and be ready to break up camp at 6:30.”

A Curtiss-Herring at Mineola airfield in the early days of aviation. Library of Congress

Springs did as instructed, and at 7:00 a.m. on Tuesday, September 18, he and approximately 150 other cadets boarded a train bound for Long Island City. Once they arrived, remembered George Vaughn, they were taken on a tugboat to SS Carmania of the Cunard Line. “Since there were not supposed to be any troops abroad, we were boarded via rope ladders on the river side, where we could not be seen from the dock.”

Carmania wasn’t the first vessel to transport American aviators across the Atlantic to Europe. A month earlier RMS Aurania had sailed from New York to Liverpool with a detachment of fifty two cadets under the command of Capt. Geoffrey Dwyer, including 1st Lts. Bennett Oliver and Paul Winslow, both of whom had been obliged to take their turn on watch, their eyes scanning the gray ocean for signs of dreaded German submarines. Half an hour before midnight on August 30, Winslow had spotted a light in the distance. “It was Ireland,” he wrote in his diary, “and nothing ever seemed so good as the sight of something indicating land, as it meant we were safe once more.”

The mood among the second contingent of American flyers destined for Europe was carefree; the men were unconcerned by the prospect of submarine attack. After nearly three weeks of being stranded at Mineola they were finally on their way to war, and wrapped tight around them as they scaled Carmania’s rope ladders was the invincibility of youth.

Carmania, launched in 1905, was the pride of the Cunard fleet, powered by steam turbines with a speed of eighteen knots. The aviators were shown to their quarters in first class along with a handful of civilian passengers, some army officers, and forty Red Cross nurses. “The boat we have is a very good one,” wrote Vaughn to his family. “There are a lot of regulars with us, mostly infantry, and all riding in the steerage, and I guess it is not too pleasant down there.”

For Vaughn and his fellow aviators, however, the voyage was “just like a vacation trip for us; lots of sleep, excellent food, deck chairs and all our time to ourselves.”

Once she left New York on Tuesday, September 18, Carmania headed north to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where it arrived two days later, joining a convoy of ships teeming with New Zealand infantrymen.

The following day, September 21, the fourteen-strong convoy slipped out of Halifax and into the Atlantic. “As we came thru from the inner basin down the river south to the sea we passed the British battle cruisers, their bands all playing ‘the Star Spangled Banner,’” wrote Grider in his diary, “and their crews cheering with their well-organized ‘Hip Hurrah,’ the ‘Hip’ being given by an officer thru a megaphone. As we were coming out of the inner basin, one of our convoy steamed past us with one lone bugler playing our national anthem and everyone on board standing rigidly at attention. I never had quite such a thrill from the old tune before.”

With North America behind them, the aviators settled into a routine for the twelve-day passage to England. The only disagreeable part of the day was the hour of calisthenics each morning, led by Springs, who also oversaw a daily boat drill each afternoon. Otherwise the aviators could do as they please. “The only distinction between us and the regular first class passengers is our uniform,” wrote Vaughn.

There were daily Italian lessons, taught either by Capt. Fiorello LaGuardia, a New York congressman who had enlisted in the Aviation Section, Signal Corps, following the outbreak of war; or Albert Spalding, a celebrated concert pianist with the New York Symphony and an enlisted man when he first boarded the Carmania. But upon hearing of Spalding’s presence, Springs persuaded Major MacDill “to move him up from steerage to a vacant stateroom.” La Guardia brought with him two of his ward bosses as cooks, and soon Springs was writing his parents to explain that, despite the daily calisthenics, he was “getting fat as a pig.”

If the men weren’t eating or exercising or learning Italian, they were enjoying the ship’s myriad activities. “We have the usual shipboard games, shuffle board, etc., to amuse us,” wrote Vaughn. “All kinds of deck chairs, reading rooms, smoking rooms and lounges to sit around in.”

What better place than a deck chair or smoking room for the 150 aviators to become better acquainted, to swap stories, and to compare experiences of their introduction to flight?

As Carmania made steady progress toward Europe, the young aviators who weren’t on submarine watch or confined to their cabins by seasickness continued to exchange experiences. They compared notes on what they’d been taught at ground school about active service: how a pilot “must be constantly on the alert against attack from below, behind and above as well as from in front”; the importance of watching the wind in case its direction should turn; the necessity of always having “a landing field in sight in case the motor goes bad”; how an aircraft’s machine gun is not accurate beyond three hundred yards; and, most important of all, the fact that an airplane “is usually invisible when it is on your level and over two miles away.” What that meant, the instructors had drummed into their pupils, is that should you glance over your shoulder for seven seconds to check for hostile aircraft, an enemy in front of you “would have passed you although it was out of sight when you first turned round! Such a thing is easily possible with a speed of 120 mph.”7

As Carmania approached the west coast of Ireland, some of the men sat down to write letters home, ready to mail them the moment they stepped ashore. On October 1, George Vaughn wrote his family, “I think we will probably land to-morrow, and I will start writing now, in order to send this off as soon as possible.” He went on to describe the voyage, the games they played, the Italian they learned, and the “excellent” food they enjoyed. As to the future, Vaughn explained that none of them knew what that held: “Even the major [MacDill] does not know what we do or where we go when we land so I cannot say much anyway…[Y]ou will know everything is o.k. when you get it through, and that is all that is necessary. Will write again as soon as possible.”

Elliott Springs was in an ebullient mood when he wrote his stepmother on the eve of their arrival in Europe. “Gee, it’s great to be alive and you can’t imagine how rosy this existence has become. I feel like a prince now,” he began, concluding, “I feel now that I can make good and all I want is a chance to do it. I have gotten away with this so far and it’s given me unbounded confidence in myself that it will take a lot to shake.”

The emotions of John McGavock Grider were less bullish, more melancholic. A few months earlier, down in hot, sultry Arkansas, he had written his sisters of his wish to go to Europe to “raise hell.” It was easy to be brave thousands of miles from the frontline. But now he was about to arrive in Europe, where, for over three years, men had been slaughtering each other in unimaginable numbers. Nearly two weeks at sea had given Grider ample time to think—about his life thus far, about the future, and about the two young boys he had left far behind. “There’s a full moon tonight and the sea is beautiful,” he wrote in his diary. “Oh for words to describe it! it makes me sad and makes me ache inside for something, I don’t know what. I guess it’s a little loving I need.…I have always longed for better things but didn’t know how to go about getting them. But now Fate has tossed me this opportunity. I must make the best of it! All I have to pay for it is my life.”

On October 1, as they came within sight of Ireland, Grider wrote his youngest son, George, on the day of his fifth birthday:

Dear little George or should I say big George, now it’s your birthday. Don’t you feel big? I wish daddy could see you and give you five big kisses and a hug. I want you to know daddy is thinking of his boys tonight and of you sweet child. I remembered your birthday and am enclosing some money for mamma to buy a present with. Daddy is on a big ship now, going across the ocean and when you get this you will know he’s gotten across safely and is in Italy, flying an aeroplane and thinking of his darling little boys at home. If I had you and John here I would be perfectly happy. I may come home next fall, son, and you and John must be good and learn how to read and write lots of things. I bet you have grown a foot. I would rather see you both tonight than anyone in the world.

George, you and John must never forget me. And never forget that I love you better than anyone else in the world.