The intrepid Fred Libby claimed fourteen kills with the British, most as an observer and most before America had even entered the war.

The King and the Cowboy

On Friday November 2, 1917, the same month that Elliott Springs was posted to 74 Squadron, the Repository newspaper in Canton, Ohio, carried a photo of Captain Frederick Libby, under which was an article describing him as an “American ace of British fliers.” Libby was in the news because he was in the United States, no longer a member of the RFC but a newly appointed instructor in the Aviation Section, Signal Corps.

Libby had actually arrived in New York a fortnight before the article appeared. With him was another American aviator who had flown in the RFC, Captain Norman Read. The pair split for the weekend, with Libby accepting the hospitality of his cousin at his Long Island home. When Read and Libby met up on the Monday morning, they took a train to Washington to report to the Signal Corps. On the train south they described their weekends. Neither had much good to say about the experiences. “They all want to hear horrible things,” said Libby. “Certainly, the war is no picnic, but who the hell wants to talk about war all of the time, just to satisfy curious people?” In short, he added, “small-town talk gives me a pain in my rear.” Read agreed. It would be good to be back among military men.

The next day Libby and Read reported to the adjutant general’s office in Washington. They received a glacial welcome from a major who didn’t deign to get to his feet. Nor did he ask about their experience in France, or show any interest in their backgrounds. Instead he told the pair they must shed their British uniforms, swear an oath of allegiance to America, and then start at the bottom as junior military aviators without wings, training on Curtiss Jennys. It was all too much for Read. “In a language this bird can understand [he] tells him to shove his wings, the Jenny and his damn commission where it will do the most good,” recalled Libby. Then Read jumped to his feet, banged the desk of the startled major and yelled: “Your treatment of us today is unbelievable! Libby has had two years of RFC in four fighting squadrons, has more hours in the air and more enemy ships to his credit than any American. All of this you must know. He is the only American with a real record.”

The intrepid Fred Libby claimed fourteen kills with the British, most as an observer and most before America had even entered the war.

Born in the small cowtown of Sterling, Colorado, in the summer of 1892, Libby experienced his first tragedy before he turned four. His mother died, and young Fred was reared by his father and his big brother, Bud, who taught him how to break horses to ride. By the time he was eighteen, Fred Libby was breaking horses for a living in the Mazatzal Mountains in Arizona. In the years that followed, the horses, and his sense of adventure, took Libby to Colorado, New Mexico, and Washington State. In the summer of 1914 Libby and a friend took a train to Calgary where they heard the Canadian government would offer good support to people wanting to work on the land. Libby had it in mind to build a ranch, but, a few weeks after his arrival in Calgary, Canada and the rest of the British Empire declared war on Germany.

The war had nothing to do with Libby but he sauntered over anyway to one of the many recruiting rallies in Calgary, curious about the crowd of young men gathered outside. “Three dollars and thirty cents a day, every day including Saturday and Sunday, with everything furnished, a chance to travel, starting immediately, tomorrow, no training required.”9 Hell, thought Libby, when he learned of the deal, why not? He had just turned twenty-two, had no ties or responsibilities, and no reason to idle away his youth in North America while over in Europe was the chance to taste glory in war.

Less than a year later Libby was in France with a Canadian motorized unit, trying to reconcile himself to the fact that it was his own choice that he was up to his knees in mud.10 “Such rain I have never seen,” he wrote in his memoirs. “With water everywhere, it is impossible to keep dry, and along with the weather there are the damned rats, cooties and, just a rock’s throw away, our enemy, the Hun.”

Then, in early 1916, Libby spotted a notice pinned to the bulletin board of his unit’s orderly room. The notice sought volunteers for the RFC, specifically observers who would be given a thirty days’ trial with the possibility of a commission at the end of that period. Libby knew nothing about airplanes, nor what an observer was required to do, other than “observe” something, but he did know one thing: “It might be a nice way out of this damn rain.”

Libby put his name forward, and, a few days later, he was standing before a colonel in the RFC. The British officer asked Libby what he knew about airplanes. “Absolutely nothing,” replied the American, but explained that he could break a horse. The colonel roared with delight, “as he was the owner of several polo ponies.” The interview took on a more equine nature and, at its conclusion, Libby was informed he would be given a thirty-day trial as an observer.

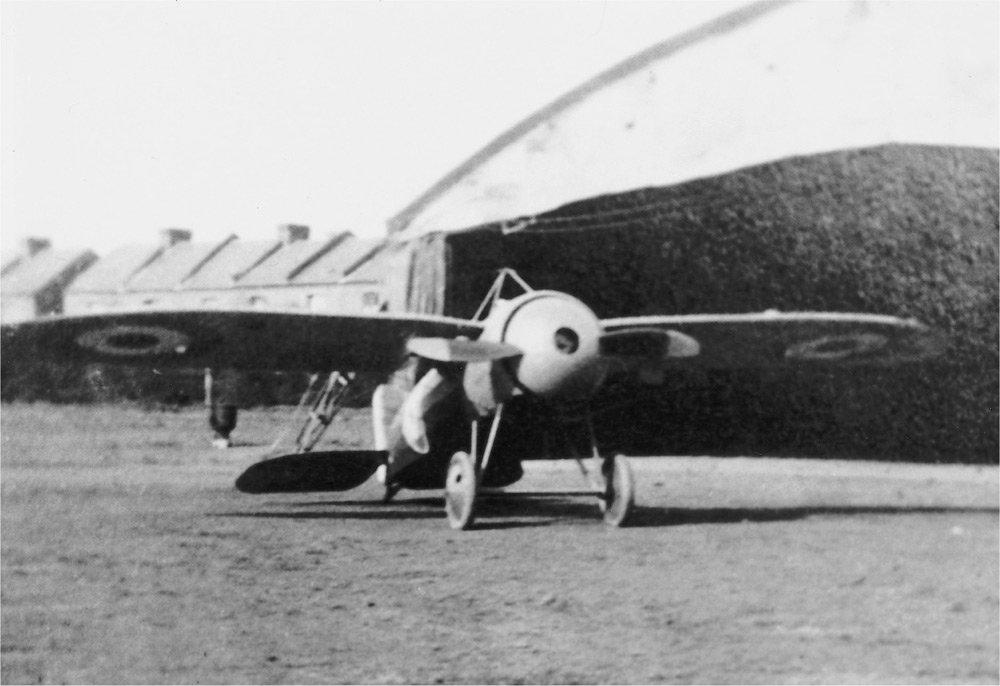

Libby was posted to 23 Squadron, based at Le Hameau, ten miles west of the town of Arras; the unit had recently arrived from England in their F.E.2b two-seater biplanes. There were eighteen of the aircraft when Libby arrived at the aerodrome, which appeared to him to be nothing more than an abandoned field with nine canvas hangars. Once the introductions were over, Libby was asked what he knew about machine-guns. As little as knew about airplanes, he replied. Libby was given half an hour’s shooting on the firing range with a Lewis gun. When he returned an F.E.2b was waiting for him on the runway, piloted by Lt. Stephen Price. Libby was horrified, not only at the prospect of going up in the air for some target practice but at the “ship” before him.

Captain Stephen Price was so impressed with Libby’s sharpshooting as an observer in F.E.2bs that he took the American with him when he became commander of 11 Squadron in 1916.

The F.E.2b was known as a “pusher” aircraft: the engine was at the back, “pushing” the machine. Aircraft with their engines in front were known as “tractors” because they and the propeller pulled the machine through the air. “Pusher” aircraft had a reputation for stability and for excellent visibility, and the enormous engine to the rear of the pilot and observer offered a measure of protection from the bullets of a surprise attack from behind. But the aircraft also had a couple of deadly drawbacks. Any loose object—such as an ammunition drum or a map case—could easily be sucked into the rear-mounted propeller in mid-flight, with fatal consequences. And if the F.E.2b was forced to crash land, the chances of survival were slim. Far more likely both the pilot and observer would be crushed to death by the engine.

Libby was 5 feet 9 inches tall, so not a particularly small man, which caused him some problems, as he explained in a letter:

The pilot was in front of the motor in the middle of the ship and the observer in front of the pilot. When you stood up to shoot [in the F.E.2b], all of you from the knees up was exposed to the elements. There was no belt to hold you. Only your grip on the gun and the sides of the nacelle stood between you and eternity. Toward the front of the nacelle was a hollow steel rod with a swivel mount to which the gun was anchored. This gun covered a huge field of fire forward. Between the observer and the pilot a second gun was mounted, for firing over the F.E.2b’s upper wing to protect the aircraft from rear attack.…Adjusting and shooting this gun required that you stand right up out of the nacelle with your feet on the nacelle coaming [sic]. You had nothing to worry about except being blown out of the aircraft by the blast of air or tossed out bodily if the pilot made a wrong move. There were no parachutes and no belts. No wonder they needed observers.

Libby judged his first flight a disaster. At the first pass, the goggle-less Libby couldn’t even see the target (a large gasoline tin) because his eyes were streaming from the rush of wind; on the second pass, he fired the entire forty-seven-round drum from the Lewis gun, hitting the tin, but losing the empty drum as he replenished his ammunition. The discarded drum narrowly missed both the head of Lieutenant Price and the propeller, and Libby returned to earth crestfallen.

However, the British were delighted. The fact he had hit the target was a bonus, they told the American, but his greatest accomplishment was in firing at all. “I have seen them freeze and never shoot,” said Chapman, the gunnery sergeant. “Shooting from the air, where you are all exposed, with nothing but your gun to keep you steady, is why so many men fail as observers.”

Libby was given twenty-four hours to learn as much as he could about identifying enemy aircraft—how to tell if the small silhouette in the distance was a German Fokker or Albatros, a French Nieuport, or one of their own Bristol scouts.” The pilot to whom he was assigned, Lt. Ernest Hicks, formerly a postal inspector from Winnipeg, offered some advice to Libby:

The rear gun is to keep Fritz off your tail when returning home from across the lines, when you can’t turn and fight with the front gun. If this happens, you lose your formation back of the lines and have to fight your way home alone. This is tough and is just what the Hun is after. A lone ship they all jump on, so we try to keep formation at any cost if possible. Fighting your way home in a single ship, the odds are all in favor of your enemy. The wind is almost always against you because it blows from the west off the sea—this they know and they can wait.…[S]hoot at anything you see and don’t know.

Libby learned quickly, but he was also a natural. “Aerial gunnery is ninety percent instinct and ten percent aim,” he wrote in a letter, proving it on July 15, 1916 when, on a patrol with Hicks, he shot down his first enemy aircraft.

Such was Libby’s prowess that when Lieutenant Price was promoted captain and appointed a flight commander of 11 Squadron—also stationed at Le Hameau—he took the American with him. On August 22, Libby was given credit for shooting down three LFG Roland C.IIs, reconnaissance aircraft that like Libby’s own “ship” comprised a pilot and observer. “Two bursts and he is upside down, then into a spin,” wrote Libby of one victim. “I thought Price would jump out of our ship he was so happy.”

Though the British Bristol M.1C was powerful, the Air Ministry didn’t trust it because it was a monoplane.

The observer’s half wing was looked down on by some pilots, but great courage was required to perform the unenviable role. This observer, R. C. Dunn, fell to Manfred von Richthofen in 1917.

Three days later, August 25, Libby shot down another aircraft, this an observation machine called an Aviatik C. He had now downed five aircraft, the number that qualified a pilot for “ace” status. But observers didn’t receive the credit bestowed on fighter pilots. They were very much the poor relation within the RFC. Another American observer in the RFC, Arch Whitehouse, recalled the occasion in 1917 when he asked squadron orderly if there were any special insignia for his tunic.

“When you’ve done your first fifty hours over the line—and you pass all your ground tests—you get your wings. Then perhaps you’ll be sent home to England for a commission and pilot training.”

“A commission?” I positively glowed.

“Perhaps, that is,” he added cautiously. “Anyway, you get your wing. It’s a single-wing idea with an ‘O’ at the bottom.” He leaned over again and whispered: “’Ere, we call it the flying arse-hole.”11

Most observers, however, referred to themselves as P.B.O.s—Poor Bloody Observers—who performed the most dangerous job in the RFC. Nonetheless when they sewed the “flying arse-hole” on to the left breast of their tunic there was a feeling of overwhelming fulfillment. “This wing I shall always be proud of,” wrote Libby when the time came for him to pick up the needle and thread. “When I think of all the observers who have ‘gone west’[died] that were flying when I started, I have indeed been awfully lucky.”12

Luck had played a part in Libby’s survival—luck in having a pilot as skilled and calm as Captain Price—but his aggressive instincts were also a factor. In tandem, the pair were a match for any foe. “We were greatly outnumbered by the enemy,” wrote Libby of his first “dogfight.” “Here I learn the true value of a cool, experienced pilot like Price, who is alert and able to maneuver so the observer can keep the front gun in action, as in a dogfight the back gun is useless for the quick action necessary to keep the enemy from shooting you loose from your tail.”

On September 26, Libby, by now commissioned as a second lieutenant, was awarded the Military Cross, one of the most prestigious gallantry medals in the British military. “As an observer, he with his pilot attacked 4 hostile machines and shot one down,” ran the citation. “He has previously shot down 4 enemy machines.”

In November 1916, Libby left France for England, and the School of Aeronautics, where for several months he learned to be a pilot and also collected his Military Cross from King George V at Buckingham Palace. For a cowboy from Colorado, the pomp and ceremony of the British monarchy was bewildering. Everywhere Libby looked in the palace were men in white wigs, boys in bright uniforms, and ornaments that dazzled. Luckily he had Stephen Price for support, also there to have a medal pinned on his chest. “He seemed very tired,” Libby wrote of the king. “This damned war must be hell for him.”

The ceremony over, Price and Libby left the palace and were photographed outside by the British press, all eager to make the most of the American cowboy who had just met the British monarch. Also waiting for Libby was Walter Hines Page, U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom, with an invitation to dine at the Embassy.

Libby returned to France in late April 1917, joining 43 Squadron who were flying Sopwith 1½ Strutters, a two-seater aircraft that, despite its rotary 130-horsepower engine, was easy prey for the German Albatros D.I fighters.

Libby’s presence was badly needed in 43 Squadron; that month, “Bloody April,” they had suffered thirty-five casualties. Morale was low but Libby lifted the spirits with his reputation and his accent. “Everyone is kidding me now that America has declared war on Germany with good natured jibes such as ‘How did you get here so soon?’” he wrote.

On May 6, Libby claimed his first kill as a pilot, “by simply pulling up the nose and pressing the control” of the front-facing Vickers machine gun. By the end of the month he was an acting flight commander, and in possession of a Stars and Stripes, a gift from a fellow officer who bought the flag while on leave in London.

As a flight commander, Libby was required to tie two colored ribbons, called streamers, to the struts of his aircraft to denote his rank (the second in command tied one streamer). Major Alan Dore, the squadron C.O., “upon seeing the flag, suggested I use it as a streamer or streamers just to show the Hun that America had a flyer in action.” Libby cut the flag into two streamers and on May 28 flew with them on a patrol over German lines, continuing to do so for the rest of the summer.

He added three more victories to his total in the following months—the last two as a captain and flight commander in 25 Squadron—to take his tally to fourteen by the end of the summer of 1917. Then in early September Libby was told he was going home to the United States, whether he liked it or not. He was needed to train up America’s novice aviators.

Libby’s arrival back home after three years overseas was a disorienting experience for a young man still only twenty-five years of age. Having encountered the prurience of his relatives and the envy of his superiors, Libby was confronted with the zeal of the public when he returned to New York after his ordeal in Washington. After agreeing to auction his Stars and Stripes streamers to raise money for the Liberty war bonds drive, Libby was the center of attention when the auction was held on the steps of Carnegie Hall. His streamers were the second item on the bidding list, after the ribbon from a French Legion of Honor. That went for a six-figure sum prompting the auctioneer to announce as he unfurled Libby’s streamers: “If the cordon of the French Legion of Honor is worth a million dollars, how much is Old Glory worth?” Bidding was ferocious, with the New York police department, the American Exchange National Bank, and silent movie actor William Farnum among those vying for the potent symbol of the American spirit. Eventually the flag was sold to The National Bank of Commerce, for the staggering sum of $3,250,000.

The American flag carried into battle by Fred Libby sold for a staggering $3,250,000 during an auction at Carnegie Hall in New York. Library of Congress

The New York Tribune described the scene outside Carnegie Hall:

A timid young officer with a tattered thing in his hand mounted the Liberty Theater platform yesterday, and while he stood there, cheeks burning with embarrassed red and eyes looking straight down his nose, a crowd that the moment before had gaped and grinned and jostled, after one slow stare, stormed toward him with sudden passion. They rolled forward in a tumult of noise, men and women with welcome in their voices and tears in their eyes—not Fifth Avenue sightseers cheering a show but a people greeting their own hero.…The first American flag to fly over the German lines, in the hands of the aviator who carried it there, had come back to New York to be baptized with the tears and kisses of a motley New York throng. Those hundreds sought to grasp the precious stripes of red and white and to shake the hand of Capt. Frederick Libby. This torn old thing, amid all the bright flags of Fifth Avenue, was a holy banner and so the procession passed along, touching a rag as though performing a sacrament. Some touched it lightly. Some shook it lightly, some shook it as if it were a paw. The women kissed it, the soldiers saluted it, while Captain Libby still tried to hide behind it with the shame that any real hero seems to have for their own valor.