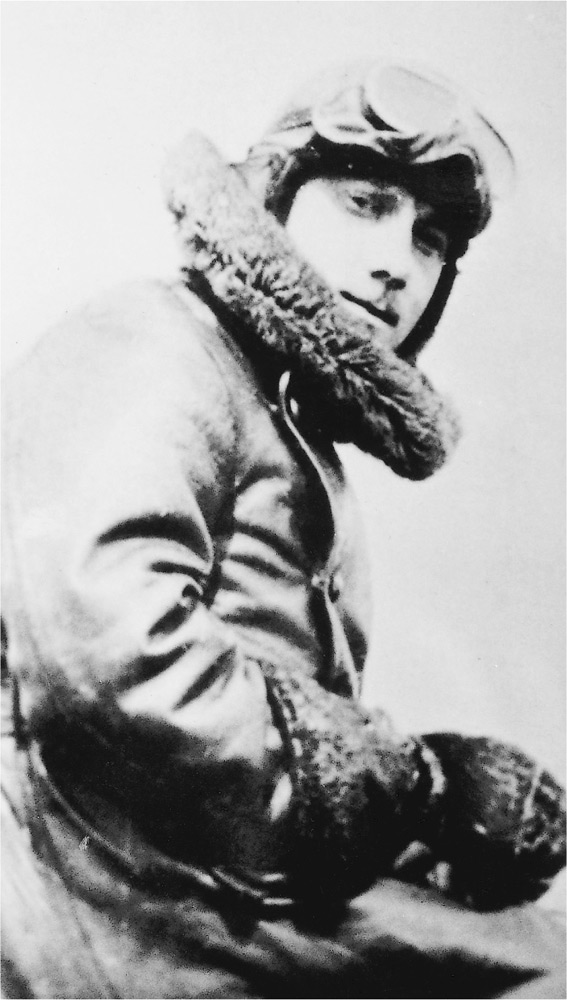

The son of a federal judge, Reed Landis was among the original fifty-two cadets who sailed to England in August 1917 aboard RMS Aurania. He finished the war an ace with twelve kills.

The Cream of the Cadets

In the same week of February 1918 that Harold Bulkley was buried, Elliott Springs wrote his father from his quarters at London Colney. “The Three Musketeers have extinguished themselves again in high society. Yes, we went raspazassin the other night—Callahan, Grider and myself—and not since the days of Oxford did we burst forth with such glory.”

Springs’s father had no idea what his son was talking about. “Raspazassin”? What the hell was that? Springs explained. A “real raspazas affair” was different from “snaking,” the Musketeers’ other favorite pastime—save for flying. “Snaking” was accepting a dinner invitation from a well-to-do English family in which one was wined and dined, and in return the Musketeers told the lady of the house “all about flying and why it isn’t like riding an elevator.” The result? “You get another free meal and if you’re good at it you sort of get to be a member of the family and drop in without invitation.”

But raspazassing was different. “Say we’re out snaking and our hostess has Lady Agatha to dinner and Lady Agatha takes a fancy to us and invites us to dine with her next Thursday at a state dinner at eight and will send her car for us. Lord and Lady —— will be there as will the Hon Bertie and the Honorable Alice etc. No entertainment is expected of us—nor will be tolerated. For once the Americans will be overawed. Well, that is raspazassing.”

The raspazassing that Springs was so keen to tell his father about concerned an invitation to a dinner in which the great and the good of English society appeared to have gathered. The dinner itself was “stiff” and formal; Callahan, Grider and Springs were all a bit overwhelmed by the amount of cutlery and the breadth of conversation.

Later, the the evening took a different turn. Grider, his inhibitions loosened by port, “got very sacrilegious trying to get the titles straightened out.” So you’re Lord X, and you’re the Earl of Y, and the gentleman over there is the Duke of where?

The Englishmen found it hilarious, unaccustomed as they were to the Americans’ merry irreverence to their standing in life. Once the port and cigars were finished, the gentlemen joined the ladies in the drawing room. One lady of impeccable breeding was sat at a piano playing what seemed to Springs like a dirge. “I lazed over to our hostess and told her that Cal [Callahan] could play some native American music,” Springs told his father. “She asked him to and he made for the piano and sort of fingered it tenderly for a moment. Then he dug down into the insides of that instrument and extracted a rag such has never been heard before. The piano roared and swayed like a dozen Jazz bands and everybody began to look up and wiggle.”

One of the Englishwomen squealed with delight, and grabbing Grider exclaimed: “Do show me how you Americans dance!”

Grider was only too happy to oblige, taking the hand of the “sweet young thing” and showing her how to dance ragtime. Others followed their lead and soon the drawing room was a dance floor as the English cast off their cloaks of reserve. “The party became a regular cabaret,” Springs told his father. “One of the Englishmen did a burlesque drill with a German musket (captured at Ypres) and Mac [Grider] had to sing the Blues four times before they’d let him stop. Somebody played the piccolo and the flunkeys simply panted from their labors.”

On February 15, the roistering came to a temporary end when some of the Americans were posted to gunnery school in Scotland. The qualification for gunnery school was the completion of twelve hours of flying time in a “service type” machine—the sort of aircraft the student would fly once posted to a combat squadron.

Springs and Callahan filled the criterion and travelled north to Turnberry, a small coastal town fifty miles southwest of Glasgow; Grider had yet to qualify. There, they were reunited with a number of other cadets from the Carmania, among them Lloyd Hamilton and Donald Poler. Springs considered Turnberry to be a genteel, conservative town with no girls and no ragtime. “Everyone very snotty,” he told his diary on February 16. Three days later, Springs wrote that Reed Landis had showed up in Turnberry.

Like Springs, the twenty-one-year-old Landis came from good stock. His father, Kenesaw Landis, was a federal judge who in 1920 would be appointed the first commissioner of baseball. Landis had served as a private in the Illinois National Guard on the Mexico border in 1916. One of the fifty-two cadets who sailed from New York on RMS Aurania in August 1917, Landis was a fine-looking young man with strong features and slicked-back brown hair. But he brought to Turnberry bad tidings: Harold Bulkley and another cadet, Lindley DeGarmo—along with Elliott Springs, the first of the cadets to qualify for their commission—had been killed in flying accidents. The next day, February 20, came news of another fatal accident, the death of Donald Carlton who failed to come out of a practice spin. To lift the depression Lloyd Hamilton and three other cadets hosted a party. “Never have I seen a bunch drunker,” wrote Springs.

The son of a federal judge, Reed Landis was among the original fifty-two cadets who sailed to England in August 1917 aboard RMS Aurania. He finished the war an ace with twelve kills.

For the rest of February, Springs and his compatriots flew regularly, usually west over the Irish Sea, where they practiced their gunnery. On February 27, the Americans graduated from the gunnery school and were sent a few miles up the west coast of Scotland to Ayr, and the No. 1 School of Aerial Fighting.

John McGavock Grider arrived at Turnberry just as Springs and Callahan were departing for Ayr. He informed his fellow Musketeers that Clark Nichol had been killed at Stamford during his first solo flight. Another of the Carmania crew was gone.

Arthur Taber had soloed for the first time on January 15, 1918. He was so excited about the momentous event that he wrote a long letter home elucidating why it had taken him so long to fly without an instructor. Firstly, there was the difference in aircraft control. Some of the Curtiss JN-4 biplanes came with a stick control, others with a Deperdussin control wheel. “It is like changing from a saddle-horse, which is bridle-wise, to one which is not,” Taber explained. Then there were his instructors, five in total since he’d arrived in England. Each had a different way of coaching, said Taber:

… and I had to adapt myself to the man I was flying with; for instance, one man would fly straight and level until he came abreast if a point he wanted to make, then he would throw the machine over on one wing until the planes were nearly vertical, whirl about and flatten out again (he had been on scouts at the front); another man would make a wide and gradually sweeping turn (he had been on night bombing); another would make a moderately sharp turn, something between the two extremes, and would want me to do likewise. There is one more causing for the delay in my getting off, and that is that the eight hours of [dual] instruction were spread out over such a long period, one forgets during the interval between flights, and loses the knack.

It was a sorry litany of excuses for his own ineptitude as a pilot. The truth was that while the rest of his Oxford classmates had long since became proficient aviators, Taber was still struggling to master the basics. But at least he was alive. He owed that to his innate sense of caution, that once he was in the air verged on timidity. While Vaughn, Hamilton, and the Three Musketeers got a kick out of looping the loop and putting their “ships” into vertical spins, Taber found merely flying in a straight line a challenge. “As you fly along with the machine under complete control, you wonder what could possibly happen, and feel as safe as can be, even making allowances for the motor’s failing,” he wrote his father on January 24. “This is the time to look out for, and it is at just such as this time that good pilots are caught napping.” Taber ended his letter with a reassurance for his father: “The exercise of prudence and common sense will see you through all right, and I am putting these convictions into practice.”

Taber’s timidity hadn’t escaped the attention of his British instructors. They had no use for someone of Taber’s docility so they didn’t even bother to send him to Scotland to learn how to become a fighter pilot. Instead, they asked the Americans to take him off their hands. In February, Taber was sent over the Channel to join the American Expeditionary Forces’ 3rd Air Instructional Center in Issoudun, central France. On one of his several jaunts into Paris, Taber ran into an acquaintance from the States and complained that “he had not had enough to do in the English camp or here in France.”

In contrast, George Vaughn had impressed his British instructors so much that by the first week of March 1918, he was deemed ready to make the transition from Sopwith Pup to the S.E.5 (Scout Experimental 5). A single-seater biplane, the S.E.5 had entered service in April 1917 and proved itself fast—it could reach 132 miles per hour at 6,500 feet—and sturdy, if a little lacking in maneuverability, with its power provided by a new water-cooled 150-horsepower Hispano-Suiza 8 engine. Soon, however, the engine got a reputation for unreliability because of its gear reduction system problems, so a 200-horsepower Wolseley Viper engine was fitted. Elliott Springs also got to fly the machine in the spring of 1918 and recalled that “it would climb at 1,800 RPM to 20,000 feet in about thirty minutes.” As for its armaments, the S.E.5 had two guns—“a Vickers firing through the prop[eller] and a Lewis on the top wing.”

On March 9 Vaughn went to American headquarters in London to collect his commission, only to discover that it, along with those of all the other cadets, had come through as a second lieutenant and not a first. “Ours should be along very soon now,” he told his family. “Just as soon as they can get it straightened out in Washington.” The correct commission arrived a day or so later, along with confirmation that, as an officer, he would receive $185 a month. Glowing with pride, Vaughn completed his twelve hours of flying time on the S.E.5 and headed north to the Gunnery school.

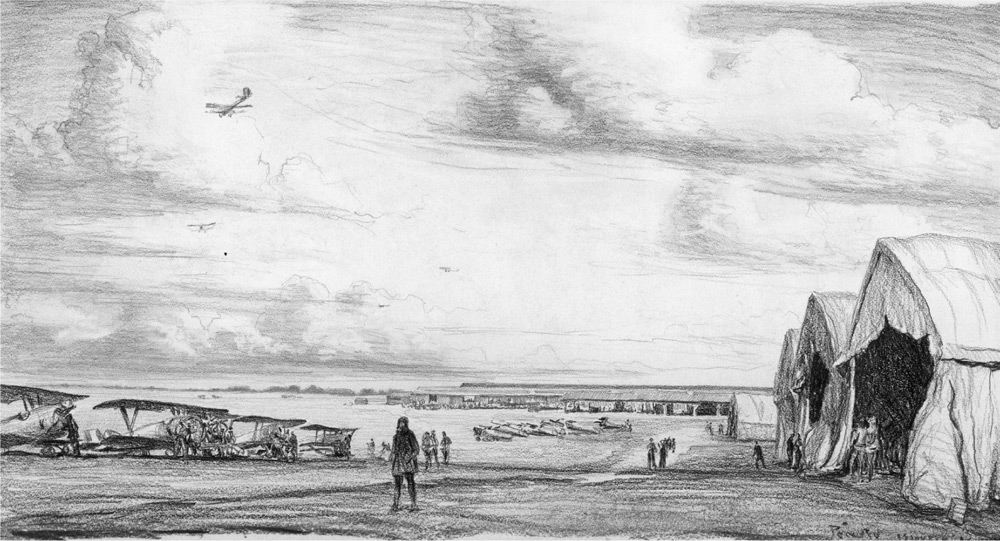

The flying field at Issoudun, central France, where Arthur Taber spent much of his time. Smithsonian Institution

He arrived in Turnberry just as John McGavock Grider finished his own gunnery course and departed for Ayr. “Your little Bud is now a graduate pilot,” he wrote his sister. “I can fly any old thing they build; I can’t fly very well yet, but I can fly safely. I have passed the crashing stage. I think I am pretty lucky, too; ten of our boys ‘went west’ [an RFC euphemism for death] in training, and not over seven or eight of the two hundred are through yet. I expect my commission to arrive in about two weeks. I was recommended five weeks ago so it should be coming along any day now.”

Grider likened his time at gunnery school to “teaching a boxer all sorts of funny side steps and counters, and then teaching him how to use them.” All in all, Grider’s prose glittered with contentment, and not for one minute did he regret leaving the plantation behind. Their shared experience had made the cadets “real friends,” explained Grider, and Scotland he described as “a wonderful place.”

The S.E.5 entered service in April 1917 and proved itself fast and sturdy. It carried a Vickers that fired through the propeller and a Lewis gun on the top wing.

Springs was pleased to see Grider walk through the door at Ayr. Though he wasn’t short on self-confidence, Springs derived a comfort from Grider’s presence that he found hard to articulate. It might have been the fact that Grider was older, more worldly-wise, and in a way, the big brother he had never had. Grider came from a loving family, but Springs had lost his mother when he was young and was at constant war with his controlling father. With Grider, Springs could broach subjects that he never could with his father.

The first thing Springs told Grider when he arrived at Ayr was the death in training of Cushman Nathan, “a fine fellow, a very good friend of mine and an excellent pilot.” Nathan was the second of Springs’s roommates to die in a month, the first being Lindley DeGarmo. That night the Three Musketeers went out on the town together to drink to the memory of Nathan.

On March 25, Springs, Callahan, and Grider travelled south to London to meet Maj. Billy Bishop, a twenty-four-year-old Canadian who had just returned from a triumphant tour of his homeland. Bishop was the RFC’s most successful fighter pilot. Holder of Britain’s highest military honor, the Victoria Cross (VC), and slayer of fifty enemy aircraft, Bishop was second only to France’s René Fonck and the great Manfred von Richthofen in the list of wartime “aces.”

Not everyone liked Bishop, particularly some of his fellow pilots who had noted that more than a few of Bishop’s “kills” were uncorroborated. Even his VC was shrouded in suspicion with no witnesses to his claim that he had swooped single-handedly on a German airfield and destroyed three aircraft as they prepared to take-off. Protocol demanded that for a VC to be awarded there must be witnesses, but, in this case, there appeared to be none, just the bullish claims of Bishop, a man who didn’t share the reticence of many of his RFC comrades.

However, by late 1917, the British Empire was in need of clean-living heroes and Bishop fitted the bill. He was shipped off to Canada where he married his sweetheart, Margaret Eaton Burden, daughter of a business magnate, in the celebrity wedding of the year. Bishop also wrote his memoirs, Winged Warfare, a thrilling account of life as an ace. “It is great fun to fly very low along the German trenches and give them a burst of machine-gun bullets as a greeting in the morning, or a good-night salute in the evening,” he wrote. “They don’t like it a bit, we love it. We love to see the Kaiser’s proud Prussians running for cover like so many rats.”

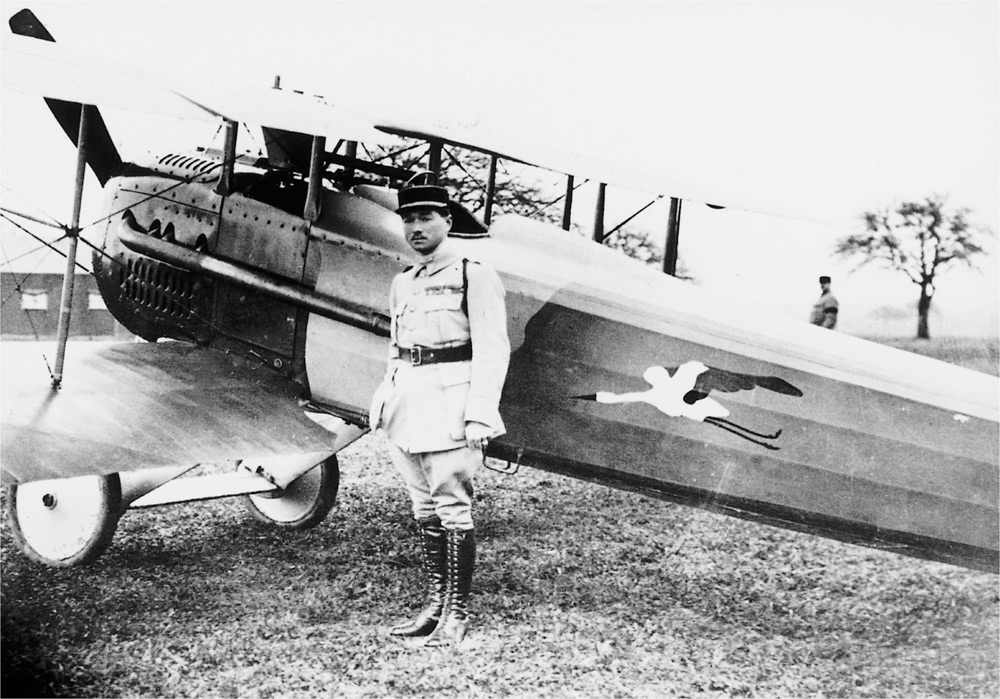

French pilot René Fonck was the leading Allied ace with seventy-five victories, second only to Manfred von Richthofen overall.

Such drivel only further antagonized Bishop’s comrades. Everyone in the RFC feared low-level strafing above all else and no one found it “fun.” As one pilot wrote home after reading the book: “There’s no doubt that he’s one of the best pilots that ever climbed into a machine, but writing about it and telling how I did this and I did that isn’t considered too good form out here.”

But the Three Musketeers were in awe of Bishop when summoned to see him in London. Upon his return to England, the Canadian had been given command of a newly-formed fighter squadron, No. 85, flying S.E.5s, and free rein to handpick his pilots. Many of those he chose he had flown with the previous year but he was also on the lookout for fresh talent, particularly from his own part of the world. One of the men selected as a flight commander by Bishop was Captain Spencer Horn, one of the senior instructors at Ayr, and an ace in Bishop’s previous squadron, No. 60. Horn’s father, William, was an Australian mining magnate and politician who had refused a knighthood because he objected to “titular distinction being made a matter of diplomacy, personal influence and barter.”

Horn told Bishop that he might want to have a look at some of the American cadets now that they were all fully qualified. Specifically Horn mentioned Springs, Grider, and Callahan. Bishop summoned them to London and found Horn hadn’t been wrong, saying later, “I knew cream when I saw it.” But when the British approached the Americans for permission to have the men sent to 85 Squadron they were knocked back; the Americans also recognized “cream” and wanted the trio for themselves.

The son of an Australian mining magnate and politician, Spencer Horn recommended Springs, Grider, and Callahan to Billy Bishop.

On March 27, Springs and his two friends sat glum-faced on the train heading north. “Back to Ayr after spending a day trying to fix it up to go overseas with Bishop,” he wrote in his diary. “It can’t be done. He’s certainly a Prince.”

But Bishop wasn’t the most famous flyer in the British Empire for nothing. Five days later, April 1, Springs told his diary: “Maj. Bishop intercedes. Capt. Horn and I throw a big party.” The American Aviation Section Headquarters in London had relented and Bishop had his men.

Grider couldn’t contain his excitement in a letter to his sister, Josephine. “Sis, I have glorious prospects of going over the lines with the fastest company in France,” he wrote. “If I make the grade, my reputation is made; if I don’t, why then I stand as good a chance as any of the other boys. I hope I make it, you will be proud of me if I do.” In addition the Three Musketeers had also received their commissions. “Your brother’s done good,” exclaimed Grider, “and I am now a real honest-to-God officer!”

Captain Edwin Benbow was another of the aces handpicked by Billy Bishop for 85 Squadron in April 1918.

On April 7 the Three Musketeers moved into an apartment in one of the most exclusive addresses in London: Berkeley Square. Their landlord was Lord Athlumney, an Englishman typical of his generation and standing. A former Guards officer he was, recalled an associate, “a strict disciplinarian and at the same time radiated considerable bonhomie, allowing everybody to call him Jim.” How the three Americans came to receive such an illustrious invitation is a puzzle, though perhaps his lordship was one of the aristocrats at the party earlier in the year when Callahan had played ragtime piano and Grider sang the blues.

In 1918, Lord Athlumney was the Army Provost Marshal of London, a man with an “unrivalled knowledge of life after dark” in the capital. It was common knowledge that he exploited his position by inviting “the ladies of the theatre to join the brethren of Athlumney Lodge after dinner and then to go on to a night club to complete the evening.”

The day the Musketeers took up residence in Berkeley Square they had what Springs described in his diary as a “big housewarming party.” Billy Bishop and his young bride were invited, as were Capt. Horn and Capt. Edwin Benbow, another ace handpicked for 85 Squadron. Among the women present were four sisters called Beard, and a dark-haired beauty from Kentucky, named Hallye Whatley, whose fragrant qualities couldn’t mask the whiff of scandal that clung to her chiffon gowns. Estranged from her American husband, the twenty-three-year-old Whatley had come to London to spice up her life. She had succeeded spectacularly, with one contemporary newspaper describing her as “prominent in the liveliest set of fashionable society.”

A week later, April 14, the Three Musketeers were joined by a number of their fellow American aviators for a party at the Elysee Hotel, close to Kensington Gardens, and within walking distance of Berkeley Square. It was a hell of a party. Grider manhandled a British officer trying to come between himself and his dancing partner, and only the intervention of Callahan saved the Englishman from serious damage. Springs, meanwhile, drank so much he lost the sight in his left eye for a couple of hours.

However, there was a reason for the excess—that is, if the Three Musketeers ever needed a reason. The next day several of the American cadets left for France to take up postings with fighter squadrons, among their number Bennett Oliver, Reed Landis, and Alex Matthews. They must have woken the following morning with more than just a sore head; probably a tight stomach would have accompanied the realization that they were finally on their way to the front line. They would have been aware, too, that the previous week Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron, had accounted for three more British pilots in two days, taking his tally to seventy-eight.

In his book, Winged Warfare, Bishop admitted the Baron was possessed of “undeniable skill,” but had nonetheless endeavored to demean the great German ace with a story about the time in 1917 he and his fellow pilots had gone pig-hunting in France. A big fat sow had been caught, wrote Bishop, and “upon her we painted black crosses; a huge black cross on her nose, a little one on each ear and a large one on each side. Then on her back we painted Baron von Richthofen. So that the other pigs would recognize that she was indeed a leader, we tied a leader’s streamer on her tail. This trailed for some three feet behind her as she walked.”

If only the real Richthofen were so easy to catch.