Oliver LeBoutillier, “Boots” to his buddies, was an American ace who witnessed the death of the Red Baron while flying with 209 Squadron.

The Red Baron’s Last Fight

April 1918 marked the first anniversary of Oliver LeBoutillier’s combat initiation. “Boots,” as he was better known, had been born in Montclair, New Jersey, in May 1894. Two days after he turned twenty-three he shot down his first German, an impressive feat for a young man who had made his first solo flight just ten months earlier.

LeBoutillier had been nine when the Wright brothers flew into history, an age when young boys are liable to become obsessed by the incredible. Thereafter he was fixated on learning to fly and, in 1916, he enrolled at the Mineola flying school on Long Island. “Win, lose or draw I had to be close to those old airplanes,” he recalled. “There was a bi-plane with two propellers driven on bicycle chains, just like the original Wright aircraft. The engine was sat right in the center of the pilot and student, the pilot on the left side and the student on the right.”

Four hours’ instruction was all LeBoutillier had on the Wright Model B before his instructor, Howard Rinehart, said to him one morning in early July 1916: “Boots, it’s very quiet, very swell, now you take off.”14

Oliver LeBoutillier, “Boots” to his buddies, was an American ace who witnessed the death of the Red Baron while flying with 209 Squadron.

So LeBoutillier took off, opening up the engine and listening to “these two big old propellers in the back clanking with these bicycle chains.” He did a lap of the airfield, landed without too much problem, and became the 566th recipient of a Fédération Aéronautique Internationale license.

LeBoutillier returned to his family and showed them his license. They weren’t too impressed, declaring he was “crazy” to want to fly. His father asked what he was going to do now with his life. “I want to fly,” replied LeBoutillier, “and the only place I know is Canada.”

His father was outraged and refused to pay his son’s fare north. But his mother did, and when the American presented himself to the RFC in Ottawa, the British couldn’t believe their luck. Here was a twenty-two-year-old in prime health, eager to fight, who was already a solo aviator, so there was no need to send him to the Curtiss Aviation School in Toronto. “They said I was just what they wanted,” recalled LeBoutillier, who was sent immediately to England aboard “an old freighter” to join the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS).

Two weeks later, LeBoutillier stepped off the ship and was directed toward the RNAS training facility at Crystal Palace, a few miles south of central London. Here “Boots” underwent his basic training and became acquainted with the ways of the Royal Navy. Time was measured in “bells” and the glass-structured palace was divided into decks as if it were a ship. To help him—and the dozens of Canadian recruits undergoing training—LeBoutillier was issued a handbook entitled The Flyer’s Guide by Capt. N. J. Gill.

On the question of learning to fly, Captain Gill had this sanguine advice for the cadets: “If you look down, do it in a disinterested sort of way without wondering how hard you will hit the earth if something happens. It won’t happen so why fill your head with rot of this kind? If you do feel that you are not quite happy, fight the feeling, and say to yourself ‘it is all nonsense!’”

Upon arriving in England in 1917, LeBoutillier was posted to the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), where pilots—such as this one—wore the blue of the navy, not the khaki of the RFC.

He also reminded them that “the word ‘joystick’ is never to be used in the Royal Naval Air Service.” As for their behavior in public, cadets hardly needed reminder that jewelry of any sort was bad form for a man and for an officer in uniform was intolerable. In addition, “Officers should not smoke pipes in the street when in uniform.” Finally, he had a word or two about etiquette in the mess: “Leave Senior Officers to themselves unless they show they want to talk to you. This is the best rule.” And above all, “never mention a lady’s name and do not use any form of swear word, or tell doubtful stories.”

Once he had passed basic training, LeBoutillier was sent to Redcar, on the north-east coast of England, to learn how to fly Maurice Farman and French Caudron machines. The Caudron was a twin-engine biplane used, since its introduction the previous year, as a bomber. LeBoutillier crashed one on his first flight. Hauled up in front of the base commander, LeBoutillier expected to be returned to the United States in disgrace but the officer was “an old Englishman, very stern but very honest, and very careful about screening students.…[H]e knew it wasn’t my fault, that the instructor had tried to push me too fast, so I got another instructor and another chance at flying, and then I did pretty good from then on.”

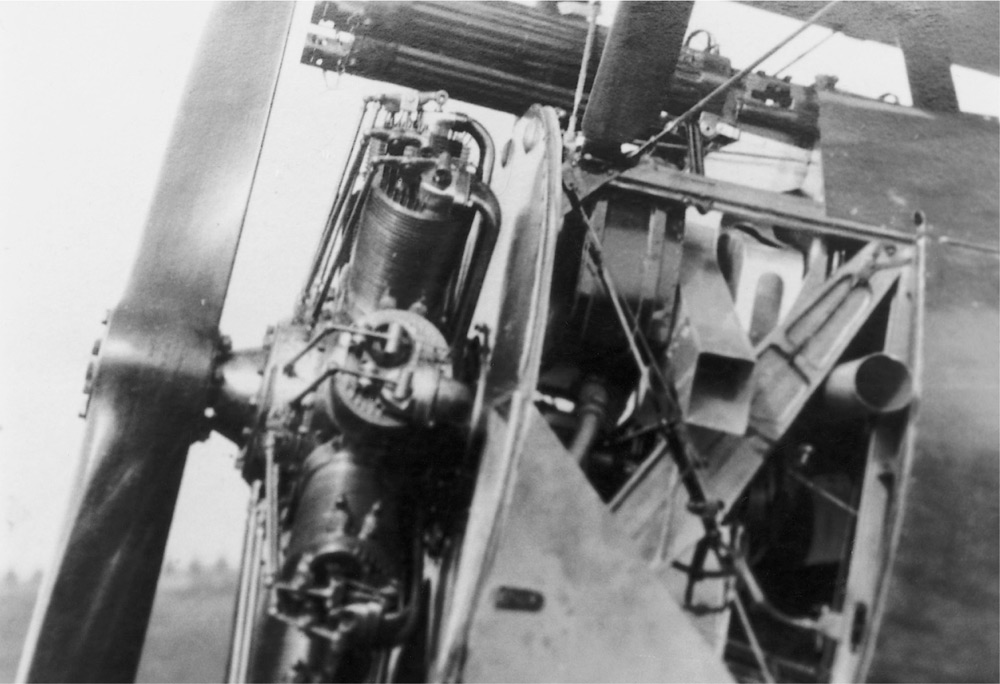

At the start of 1917, LeBoutillier was sent down south to Dover, the nearest point in England to France, just nineteen miles across the English Channel. The historic town with its white cliffs was the “checkout point for pilots flying single seaters before they went to France.” At Dover LeBoutillier was introduced to the Sopwith Camel, heralded as the superior version of the Sopwith Pup. Its armaments were indeed formidable; for the first time in a British-designed machine, two .303 Vickers machine guns were mounted directly in front of the cockpit with their synchronization gear enabling them to fire through the propeller disc. But that was one of the few positive points in the eyes of the men ordered to fly the Camel, which gained its name from the hump created by a metal fairing over the gun breeches to stop them freezing at altitude. Ninety percent of the Camel’s weight was contained in the front seven feet of the aircraft—engine, fuel tank, pilot, and guns—so it was unstable and not anything like as maneuverable as the Pup.

The Sopwith Camel was well armed but unstable and got its nickname from the hump created by a metal fairing over the gun breeches designed to stop them freezing at altitude.

In addition, the Camel’s 150-horsepower Bentley rotary engines generated so much heat that ordinary engine oil proved useless. Instead, recalled LeBoutillier years later, they “used pure castor oil as lubricant.” He continued: “At first it was pretty hard to get used to because when they start the engines the fumes came right back at you in the cockpit, and you’re breathing castor oil the whole time. The castor oil gets into your flying suit and we smelled of castor oil all the time.”

In April 1917 LeBoutillier, now a sub lieutenant, was assigned to 9 Squadron, RNAS, despite the fact he had logged only twenty-nine hours of solo flight time. The British had identified in the young man from New Jersey the traits required for a fighter pilot. These, recalled LeBoutillier, were “a certain aggressiveness…[and] the boys who seemed to be the best fighter pilots were the ones that had done things the hard way; they didn’t phase out when the odds were against them. They knew how to cope with it.”

In addition, the Camel’s 150-horsepower Bentley rotary engines generated so much heat that ordinary engine oil proved useless. They resorted to pure castor oil as lubricant, which created terrible fumes.

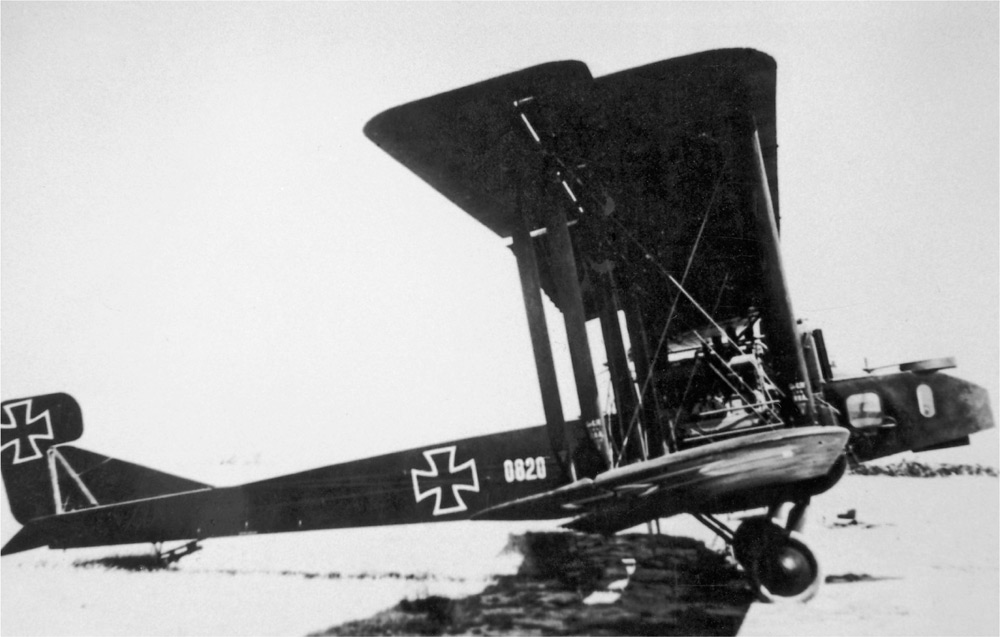

The task of 9 Squadron in the early summer of 1917 was to intercept German bomber squadrons bound for southern England. Attacks had been increasing in intensity in the preceding months ever since the Germans began replacing Zeppelins with the twin-engine Gotha bomber. On May 25, a fleet of more than twenty Gothas attacked the Channel port of Folkestone, killing seventy-one civilians, including twenty-seven children. The British were incensed, but powerless to hit back against an aggressor whose distant cities were beyond the reach of their own aircraft.

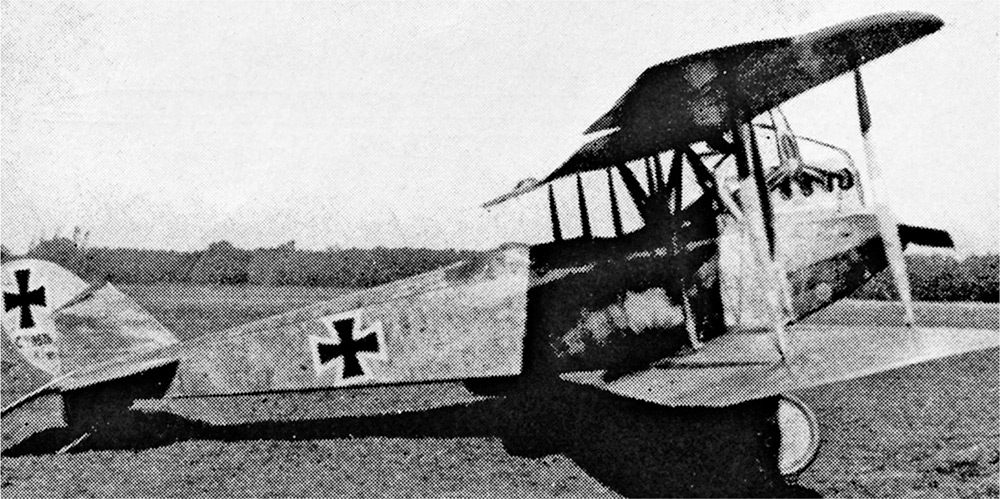

The next day the Germans came again, this time with a fleet of LVG (Luftverkehrsgesellschaft) bombers. However, they were intercepted by 9 Squadron over the Channel, and LeBoutillier claimed his first victim. Ten days later, he scored a second victory when his patrol encountered several Albatros scouts over the French coast waiting to escort a bombing mission to England. A third German fell to LeBoutillier’s guns in July 1917, again an Albatros scout, which “turned on its back and went down out of control.” At the end of the month “Boots” had four enemy aircraft to his credit.

By early 1918 LeBoutillier was one of 9 Squadron’s veterans, a captain and the commander of B Flight. On April 1, the RNAS merged with the RFC to become the Royal Air Force [RAF]. No. 9 Squadron was reconstituted as 209 Squadron, and ordered to France to help repel the German ground offensive of March 21, a mass attack along the Western Front in which the Kaiser’s army achieved the deepest advances by either side since 1914. It was the last throw of the dice for the Germans, an offensive aimed at defeating the British and French armies before the United States had the chance to bring its full weight to bear on the Western Front.

The arrival in France of 209 Squadron increased the RAF presence to sixty-three squadrons (an increase of eleven squadrons in four months thanks in no small part to the arrival of aviators from North America, Australasia, and South Africa) but of its 1,232 aircraft on the Western Front, only 580 were ready for combat at the point of attack, compared to 750 enemy machines.

LeBoutillier’s squadron was one of several based at Bertangles, close to the Amiens-Albert road, about ten miles west of the front line, while “the Germans and Richthofen were stationed in a little place called Cappy, I’d say approximately the same distance on the other side of the German line.”

One of LeBoutillier’s early tasks was to shoot down the twin-engine Gotha bombers that replaced Zeppelins as the primary aerial threat to Britain. On one raid on the Channel port of Folkestone in May 1917, a squadron of Gothas killed seventy-one civilians, including twenty-seven children.

LeBoutillier’s first kill was an LGV (Luftverkehrsgesellschaft) bomber in May 1917.

LeBoutillier’s respect for the Red Baron ran deep, and, like most RAF pilots, he knew much about his opponent. Unlike the British, as reluctant as ever to turn their top pilots into celebrities, the French and Germans had from the outset acclaimed the feats of their “aces.” Neither nation shared the British concern that by creating a hierarchy among pilots they might damage the delicate camaraderie within a squadron; might not some of these ardent young men be tempted to go glory-hunting in the hope of joining the exalted ranks of the aces; to stray from the flight formation in the pursuit of fame rather than the foe?

In 1917 Richthofen wrote his autobiography, Der rote Kampfflieger (translated into English the following year), and Germans hung on his utterances, however bland or inconsequential. Americans, too, were transfixed by the Baron. On April 30, 1917, Ohio’s Lancaster Daily Eagle was one of several newspapers to laud Richthofen, describing their enemy as “brilliant and daring.” From the newspaper’s breathless prose one wouldn’t have guessed that their country had declared war on Richthofen and his comrades less than a month earlier. The Red Baron had just been awarded the Pour le Mérite, German’s highest military medal (also known by the more informal moniker Blue Max on account of its color) by his Kaiser and the Daily Eagle told its readers: “He is the youngest man ever to receive this distinction, being twenty four years old. Von Richthofen shot down his fortieth enemy airplane, winning three air victories in a single day (on April 13, 1917).”

Six months later, in November 1917, the Kansas City Star carried the comments of Richthofen concerning the “reported preparation to place twenty thousand American aviators on the western front.” It was his opinion that these inexperienced pilots will “be unable to judge the military conditions and at least twenty-five per cent of the machines will be disabled during the long transport.”

In LeBoutillier’s opinion, Richthofen had amassed so many kills because of his sharpshooting skills. “When he was a young fellow they gave him a gun and he’d go out and shoot the upland birds,” he said. “He knew how to lead the birds so that stood him in good stead when it came to combat.…[H]is ability to lead and shoot a moving target. He had that one thing going for him.”

The Baron shot down his seventy-eighth machine on April 7, 1918, but then, recalled LeBoutillier, the weather closed in and for several days “we had heavy clouds.” For thirteen days Richthofen was unable to add to his tally but, on Saturday, April 20, the weather was fine and he bagged two more victims, both Sopwith Camels belonging to 3 Squadron.

The second of the two Camels was flown by a nineteen-year-old Rhodesian called Tommy Lewis, a rookie in combat who was easy meat for the Baron’s bright red Fokker triplane. His emergency fuel tank ablaze, Lewis found himself “hurtling earthward in flames.” His machine hit the ground at around 60 miles per hour, but miraculously the teenage flyer was catapulted clear suffering nothing more than a few minor burns. LeBoutillier heard later that “Richthofen came over while he was brushing the fire off his flying suit and waved to him. Tommy Lewis waved back.”

When dawn broke on Sunday April 21, a mist was draped over the Somme valley. The pilots of 209 Squadron had breakfast and waited for it to clear. The tension was palpable. “We knew things were going to be pretty tough that day,” said LeBoutillier. A few days earlier word had reached the squadron that “Richthofen’s squadron was getting pretty upset with 209 and they wanted to try and wash them out.”15

Although 209 Squadron had only been recently posted to France, many of its pilots were veterans having flown countless offensive patrols against German bombers the previous year. LeBoutillier was in charge of B Flight; Captain Oliver Redgate, an “ace,” led C Flight; and Capt. Roy Brown was A Flight’s commander. Brown was a twenty-four-year-old Canadian who had joined 9 Squadron in March 1917 and received the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) later that year “for the excellent work he has done on active service.”

Captain Roy Brown, the twenty-four-year-old Canadian of 209 Squadron, who many believe shot down the Red Baron in April 1918. Others believe it was ground fire from Australian infantry that downed Germany’s top ace.

The spring sunshine soon burned off the early morning mist and 209 Squadron began taking off, each of the three flights comprising five aircraft. “We had certain sectors to cover over the Somme River Valley along the front over the Morlancourt Ridge,” recalled LeBoutillier. “Underneath was the Australian artillery.”

At about the same time as 209 Squadron embarked upon their morning patrol, Richthofen and his pilots were climbing into their Fokkers twenty miles to the east, their gaudy colors a striking contrast to the vernal French countryside. The Baron was wrapped up well in his woolen flying jacket and deerskin trousers, the Pour le Mérite cross around his neck.

Once airborne, LeBoutillier led his B Flight toward the southern end of their sector at a height of 15,000 feet. “Brown was a little to the north and Redgate more or less center,” recalled the American. “I was sent south because they said there were enemy aircraft there we should take out.…[W]e took out one.” LeBoutillier, together with Lt. Robert Foster, shot down an Albatros two-seater in flames over Beaucourt but then “everything broke to the north of us.”

Sunday, April 21, 1918, dawned cold and misty on the Western Front, and von Richthofen wrapped up warmly before what he assumed would be another day of rich pickings against his British opponents.

LeBoutillier estimated that it took his flight three minutes to fly north, a lifetime in aerial combat. By the time he and his four Sopwith Camels arrived, the pilots of 209 Squadron were fighting for their lives against Richthofen’s Circus. Frank Mellersh of A Flight had shot down a Fokker while Canadian Bill MacKenzie had been wounded in a duel with a German. LeBoutillier recounted that already “we’d lost four of our planes” so 209 Squadron was down to eleven aircraft against twenty-eight Germans.

“All you saw were Sopwiths and trip-lanes, all together,” recalled LeBoutillier. “There were three or four red triplanes, but nobody knew Richthofen was in one of them.” LeBoutillier opened fire on a Fokker but missed the target and “then one chased me for about twenty seconds. I pulled out to see if my wings were all shot up.”

After shaking off his pursuer, LeBoutillier suddenly glimpsed “a pilot going under me with a red triplane after him.” Only later would he learn the British pilot fleeing for life was Lt. Wilfrid May, a young Canadian from Manitoba who had joined the squadron a fortnight earlier. Brown had taken his compatriot under his wing and now saw the danger he was in. He joined the chase, hunting the triplane that was hunting May. LeBoutillier could tell it was Brown because of the streamers attached to his Sopwith. “He came down at a forty-five degree angle on the triplane and you could see the tracers going into the cockpit,” recalled LeBoutillier. “Then he [Brown] pulled up into a climbing turn and he didn’t see the red triplane again, and I didn’t see Roy Brown again because I had my eyes on the triplane, which broke off from chasing May and at that time he started to make a great big gentle turn to the right.”

LeBoutillier saw the triplane land in a field on a hill near the Bray-Corbie road. “He didn’t hit too hard, hit on his wing-tip and right wheel and he hopped along the ground a little bit and stopped.” LeBoutillier “came down, made a pass over, so I could go back and report it to the squadron.” As he made his pass, the American noticed Australian soldiers on the ground.

They were the first to reach the downed triplane and to their amazement soon learned the identity of the pilot. Later that day word reached 209 Squadron that it had been the Red Baron himself in the downed triplane, the great man killed by a single bullet. The Australians claimed they’d fired the shot but that made no sense to LeBoutillier. “Richthofen had one bullet that went in his right shoulder at a forty-five-degree angle, that went through his body, at the same angle that Brown was firing at him,” he reflected. “So they can say what they want about ground troops…but in my opinion von Richthofen was hit by Brown.” The debate over who killed Richthofen continues to this day.

Instead of becoming the eighty-first victim of the Red Baron, Lt. Wilfrid May, a young Canadian from Manitoba, became known as the man who caused him a moment of fatal complacency.

Von Richthofen’s bright red Fokker triplane was swooped on by souvenir hunters, all eager for a piece of the legendary Red Baron. The pilot who had decorated his own quarters with trophies taken from his eighty victims was a mute witness to the desecration of his legendary aircraft. “Our mechanics went over there and cut a piece of fabric from von Richthofen’s aircraft,” remembered LeBoutillier. “And the eleven pilots in that combat fight signed it.” Above the signatures someone wrote, “Piece of fabric from Baron von Richthofen’s aircraft, shot down by Roy Brown.”