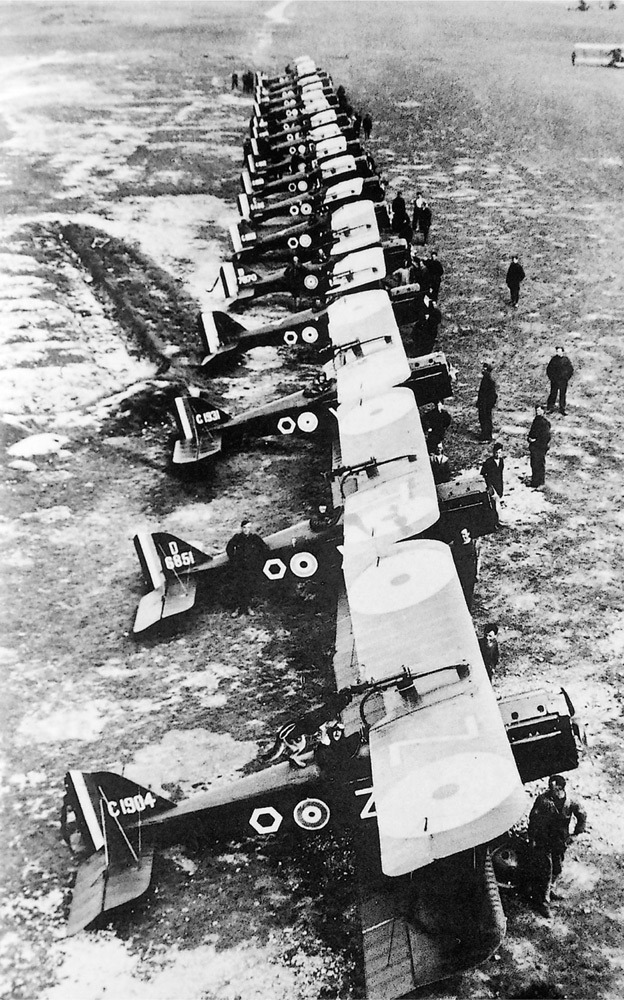

Some of 85 Squadron. From left to right: Springs, Horn, Langton, Callahan, Dymmand, Thompson, and Brown.

Am I to Blame?

May 1918 found Arthur Taber still at the 3rd Air Instructional Center in Issoudun, as far away from becoming a fighter pilot as ever. Instead, as he explained in a letter to his parents, he was the center’s officer of the guard, “keeping records and doing paper work all day, and inspecting every guard on his post in the camp three times a night.” Ever the dutiful son, however, Taber made sure he wrote to his mother on May 12 to wish her a happy Mother’s Day, and to assure her he was being as virtuous as ever. In fact, only that morning he had been at Sunday service where the sermon centered on “the responsibility of the men in the A.E.F. to live straight so that they may go home untainted and fit to cope with the problems of America as the greatest world-power.”

Nearly a fortnight later, Saturday May 25, the ladies of the Red Cross canteen gave a dance for the Center’s officers to which “several truck-loads of nurses were imported from a hospital near here.” Taber rated the nurses “not too impressive,” but fortunately the refined ladies of the Red Cross were more to his delectation and he “found several good dancers.” It was, he told his sister, an enjoyable evening and he hoped “more of such hops will be held for a diversion.”

On the same Saturday night that Arthur Taber was dancing with the ladies of the Red Cross canteen, the Three Musketeers were still settling into their new home at Petite Synthe, just a couple of miles from the French coastal city of Dunkirk. Elliott Springs wrote his father that he “was at peace with the world.” The move to France had intensified the camaraderie within 85 Squadron and Springs was writing the letter moments after Billy Bishop had provided some entertainment by inadvertently using cold cream for toothpaste. Boy, how they’d laughed—all except Bishop’s orderly.

Some of 85 Squadron. From left to right: Springs, Horn, Langton, Callahan, Dymmand, Thompson, and Brown.

The airfield at Petite Synthe was in a rough triangle “between the main railway line from Dunkirk to Calais, the by-road running from Petite Synthe to Pont de Petite Synthe on the Bourbourg Canal, and the sidings of the railway on which hospital trains belonging to the French Medical Corps were drawn up.” Springs’s equable state of mind may also have owed something to the surroundings: the aerodrome was appealingly bucolic, a delightful patchwork of colors—varying shades of greens, browns, and grays—with the road to the squadron’s home lined by a row of tall, elegant poplars.

There were no dances or parties for 85 Squadron that night, nor would there be for the foreseeable future, but Springs wasn’t bereft. On the contrary, as he told his father, “it’s a great relief to be sure that it will be at least six months before you’re going to see a woman again, that is anything eligible.…[Y]ou should see the difference in the squadron in France and in England. In England the chief consideration is feminine as in the States and the fellowship is somewhat neglected. Over here the detraction and distraction is removed and you can see what a man’s world is really like. And strange to say, our social graces improve. We don’t lapse into a state of degenerate coma as is the popular supposition. Woman’s refining influence is not missed at all.”

The next day, Sunday May 26, Springs and the other untested pilots of 85 Squadron began familiarizing themselves with their sector, under the eye of Captain Horn. The squadron was scheduled to become operational on June 1, but Bishop couldn’t wait that long. Out of combat since April 1917, he went out looking for the enemy and he soon found one. “The major bags a Hun!” wrote a starstruck Springs in his diary on May 26. “Major Bishop is unquestionably the greatest fighter of the age.”

John McGavock Grider thought so, too, exhorting his sister in a letter to buy Bishop’s book. “It will you give you some idea of the man I am with,” he declared. “He is one of the best and we all love him.”

On May 27, Bishop added two more victims to his score, the major setting an example that the squadron’s other aces felt obliged to match. Captain Benbow went out in hunt of a “nice fat Hun,” but encountered six and was chased back to base under fire. “He was awfully fed up about it,” wrote Springs, who found it comical that the Englishman always flew wearing a monocle rather than goggles. Benbow swore vengeance and the next day took off to find his ninth victim of the war. Instead, he found another ace, Hans-Eberhardt Gandert of Jasta 51, who shot down and killed the monocle-wearing Benbow.

The following day was another mixed one for the squadron. Bishop bagged his customary German but Captain B. A. Baker and a pilot called Brown both crashed, although neither was seriously injured.

Springs and Grider went into Dunkirk to stock up on essentials, the most important of which was toothpaste. Neither knew the French word so Springs made his desires known to the young blonde sales assistant while Grider gave a running commentary on her appearance. “You’ve got a pretty face but a square ankle,” was one of his judgments, much to the amusement of Springs, who nudged his friend in the ribs and told him to quit making him laugh.

When the time came to pay the sales assistant glared at the pair and asked in flawless English: “Do you want it wrapped or will you take it in your pocket?” The two Americans fled in embarrassment.

A graver miscalculation ensued on the last day of May, when Springs spotted a German patrol 200 feet beneath him, over Armentières. Alone but full of confidence, Springs saw that one of the six enemy aircraft was straggling behind the others. This was irresistible! If Bishop could kill at will, then so could Springs. He dived on the German and opened fire, missing the target, and alerting the rest of the patrol to his audacity. In a matter of seconds Springs was again fleeing, only this time it was to escape a “peppering” from six German fighters. “I hadn’t the faintest idea what to do,” he admitted the next day in a letter to his stepmother. “I knew what the major would do—turn and shoot a couple of them down and chase the rest of them home—but somehow or other I thought I needed a little more experience before trying that.”

Springs dived—“wondering mildly how long before my wings would fall off”—and eventually the Germans gave up the chase, and retreated back to the safety of their own lines. Back at Petite Synthe Springs was “the joke of the squadron,” with Grider “in hysterics” at his friend’s foolhardiness.

Bishop was less amused. Springs had fallen for the same trick that Benbow had a few days earlier, attacking a “straggler” when in fact he was the bait laid by the Germans. For the next few days, Bishop told Springs, he would “tag along” with him so he could better keep an eye on the impetuous American.

The next day Springs, now considered the secretary of the “Sadder-but-Wiser” club, went on patrol with Bishop, Horn, and Capt. Malcolm McGregor, a New Zealander with two kills to his credit. It wasn’t long before they spotted the German patrol, with what Springs called “my six friends” laying the same trap for their enemy. This time, however, the hunters became the hunted, and only two of the Germans escaped with their lives. Of the other four, two were shot down by McGregor, one by Bishop, and one by Springs.23

However, Springs was still not satisfied. He set off after the two Germans fleeing east, but quickly “decided that discretion was the better part of valor.” His decision was influenced by a ferocious blizzard of anti-aircraft (A.A.) fire as he flew deeper into German territory. “About three Hun Archie batteries opened on me and the whole sky turned black,” he wrote to his stepmother. “Pooof, pooof, right under my wing tips goes Archie and my heart beats 200 higher. Pooof, pooof, he’s got my range again, dive quick, then turn and climb. This won’t do, I’ll run for it.”

As Springs knew from the veteran pilots, it wasn’t the A.A. bursts one heard that were dangerous, rather those one didn’t that did the damage. But Springs was lucky. The German gunners couldn’t get his range and he returned to base intact.24

Bishop’s remarkable success rate continued into June, the major downing six enemy aircraft over a three-day period to reclaim his mantle of leading ace from the British pilot, James McCudden. Springs failed to add to his tally, but nonetheless the fact he had one made him a “changed man.” He had shot down a German, thus proving himself a combat pilot in the eyes of the squadron, and that gave him “sensations I never knew existed before.”

Larry Callahan experienced a similar excitement when, on June 4, he, Bishop, and a Canadian pilot called Herbert Thomson, took on a German patrol. Bishop and Thomson shot down one each, and Callahan sent a long burst into his adversary. Callahan’s aircraft wasn’t seen to crash so he returned to base unable to say he had emulated Springs.25

The procedure for claiming a victory was complex for Allied pilots, as most engagements were fought over German lines, rendering emphatic confirmation virtually impossible. Upon returning from a patrol a pilot would complete a combat report in which a number was entered for one of three categories: 1) Destroyed. 2) Driven down out of control. 3) Driven down.

Once approved by the commanding officer, the form would be sent to Wing Headquarters, then Brigade headquarters, and finally on to RAF Command in France, where staff officers “had the advantage of cross checks not available at lower levels.” Using the limited intelligence at their disposal—information from observation posts and other squadron’s combat reports—they would then rate the pilot’s claim “Decisive” or “Indecisive.”

Although neither Callahan nor Grider had yet to emulate Springs’s feat of downing a German, both were adjusting to the physical demands of daily patrolling. It was early summer in France but at 18,000 feet it was still cold as hell and liable to make a pilot sleepy. (Two thousand feet higher, the average temperature was minus ten degrees.) Springs complained of such a condition in a letter home dated June 6, also informing his father that “my ears are very sore from high altitudes and long dives and my eyes are rather sore from flying without goggles.” He added that no one wore goggles when “you’re out hunting,” since painful eyes were a small price to pay for an unobstructed view. Being exposed to the elements in the small cockpit of the S.E.5a resulted in other afflictions: split lips, frostbite, and headaches. Pilots were taught to “swallow or hold your nostrils and blow to relieve the pressure on your ears” when descending; fine in training but not so practical when diving to escape an enemy patrol.

Exposed to the elements at 20,000 feet, pilots often had to improvise, as this one is doing wearing a leather mask to protect his face.

A device called a “peter tube” allowed pilots to urinate, but that was a challenge in itself when most took to the air wearing three pairs of gloves (silk as a base layer, then chamois, and then “a heavy pair of flying gloves over the lot”).

Springs, however, was blessed with an iron constitution, and could cope with the physical demands of flying. It was day-to-day living that was proving problematic in early June. “I’m having great difficulty getting liquor,” he complained to his diary. Eventually the Three Musketeers could stand it no more and, on June 6, they went to Boulogne on a booze run. “Bring back a lot,” wrote Springs. “Inside us.”

On June 11, the squadron moved twenty miles south to a new aerodrome at St. Omer. The airstrip wasn’t up to much, but everyone was impressed with their quarters; instead of the tents of Petite Synthe, the pilots were quartered in Nissen huts, and Grider considered the Mess “wonderful.” He added in a letter home: “We have a piano which Larry [Callahan] tries to paw to pieces every night, a phonograph and hundreds of the latest records, the best food in France, and one of our A.M.s [air mechanics] is an artist. He is decorating the mess hall and the ante-rooms. We are comfortable and happy.”

Grider had been blooded in combat on June 9 when he clashed with a German fighter during a dogfight. The pair had turned and half-rolled, trying to maneuver into a firing position, before the German broke off the attack and headed east “with Mac still popping at him.”

Callahan rated Grider “an excellent shot,” and a man of “very great determination [who] was willing to take any kind of chance there was.” He had only one weakness, in Callahan’s eyes: Grider “was a fairly ham-handed pilot.”

Grider told his sister she needn’t “worry about anything happening to me,” as he was in the best squadron in France; he reiterated his desire to return to Arkansas and see out his days on the San Souci plantation.

Three weeks after arriving in France, the bravado of the Three Musketeers had lost some of its luster. They now appreciated there was no dishonor in running from a fight if there were four of them and one of you; only a fool—or an idiot—would take on such odds. They had learned, too, how to watch the sun for direction when spinning or turning, so as not to become disorientated and crash into the earth, and A.A. fire they treated with respect, but not terror.

85 Squadron poses for a photograph in France, believed to be taken in June or July 1918.

June 17, 1918, was a highly important day for the Three Musketeers. In the previous nine months they had got drunk together, chased women together, trained together, laughed and cried together, and now they were going on patrol together.

Their three S.E.5s took off from St. Omer early in the morning and crossed into what they called “Hunland” at 15,000 feet. Springs saw a flash of light “five miles ahead of me and 2,000 feet below.” He waggled his wings, pointed toward the light, and led his two friends toward the target. In the German two-seater, the observer had seen the threat and was behind his machine-gun waiting for the three aircraft to come into range. What he failed to note, however, was the approach of Lt. John Canning, another 85 Squadron pilot, who had spotted the enemy aircraft at the same time as the Three Musketeers. “They dived from behind and I dived in from in front and slightly to one side,” he wrote in his combat report. “Opened fire at 100 yards and emptied one drum of Lewis and 100 rounds from my Vickers into the center section and engine of the E.A., which burst into flames.”

As Canning broke off his attack he identified Grider “right on the E.A.’s tail, his tracers seemed to be going into the observer’s cockpit.” The American’s own report on the incident concluded with his glancing over his shoulder as “the E.A. crashed in a cloud of flame and smoke.”

Back in the mess, the Three Musketeers whooped and hollered, “feeling very proud of ourselves.” Springs told everyone that he’d been so close to the burning Hun he felt the heat from the flames. Grider said he’d kept on firing till he was no more than twenty-five yards from the enemy aircraft.

The next morning, June 18, the Three Musketeers took an early breakfast of coffee, shredded wheat, and eggs benedict. The men felt no apprehension. The war was still fun. It was agreed Grider would lead this time and flush out any lonesome Germans. Out on the airfield, however, bad news awaited Callahan. His engine wasn’t firing properly, and his mechanics said they needed time to resolve the problem. Grider, meanwhile, was dismayed to discover that his lucky mascot, the doll given him by Billie Carleton, was not in his aircraft. It had been damaged the previous day, and one of the ground crew had promised to have it repaired and returned by the morning.

Callahan watched as his two friends took off into an overcast sky and headed due east toward the town of Menin in Belgium. The pair climbed to 16,000 feet and flew deep into enemy territory, their eyes scanning the sky to the front and the rear. Suddenly they saw a German two-seater several thousand feet below them and a couple of miles to the east.

This time Springs dove onto the enemy’s tail firing “one Lewis drum and Vickers from immediately behind.” The German observer, gamely standing in his cockpit blazing away with his machine gun, was trapped in a deluge of fire. Springs could see tracer rounds shredding his body. He broke away in a climbing turn, and together with Grider watched as the Rumpler reconnaissance plane toppled from the sky with neither noise nor flame.

Callahan was still on the aerodrome when Springs returned. As his friend taxied along the grass runway, the ground crew running excitedly over to hear if he had had a good morning’s hunting, Callahan continued to scan the sky. “Where’s Mac?” he asked. Springs didn’t know; he couldn’t understand where his friend had got to. However, he wasn’t worried, sure that Grider would soon appear, and entertain them all with some hilarious escapade.

At lunch there was still no sign of Grider, nor was there when 85 Squadron took their seats in the mess for dinner. Springs returned to his billet, sat on his bed and opened his diary. “Mac missing,” he wrote. “Oh Christ. Am I to blame.”