Bogart Rogers, a twenty-year-old Californian, arrived at 32 squadron in the early summer of 1918 with a devil-may-care attitude.

From Toronto to the Trocadero

On the morning of May 27, 1918, four days after the Three Musketeers had arrived in France with 85 Squadron, the third battle of the Aisne began. Four thousand German artillery guns erupted along a twenty-four-mile stretch of the Allied lines as the Kaiser’s army attacked positions on the Chemin des Dames ridge, in the Aisne River region of France, approximately eighty miles northeast of Paris.

The attack was a stunning success, German soldiers advancing behind a cloud of poison gas to reach the Aisne in just six hours. By nightfall on May 27, the German army had pushed more than twenty-five miles into Allied territory, demoralizing eight enemy divisions and seizing an estimated fifty thousand prisoners. By June 3, German troops were within thirty-five miles of Paris, and panic began to grip the city’s inhabitants.

However, Gen. Erich Ludendorff had asked too much of his men in too short a period. The German supply line began to creak, casualties mounted, exhaustion increased, and then the American 3rd Division arrived to take up positions on the south bank of the Marne near Château-Thierry. They were green troops, but they were fresh and eager to prove themselves to their British and French Allies.

So, too, were the two American pilots flying S.E.5s in 32 Squadron. Lieutenants Bogart Rogers and Alvin Callender were both untested in aerial warfare, but as anxious as the infantry to show what they could do. On Sunday June 2, the squadron commander, Maj. John Russell, was ordered to move seventy miles south to Fouquerolles, near the town of Beauvais. The role of 32 Squadron was twofold: to escort observation planes; and strafe enemy soldiers, artillery, and transport.

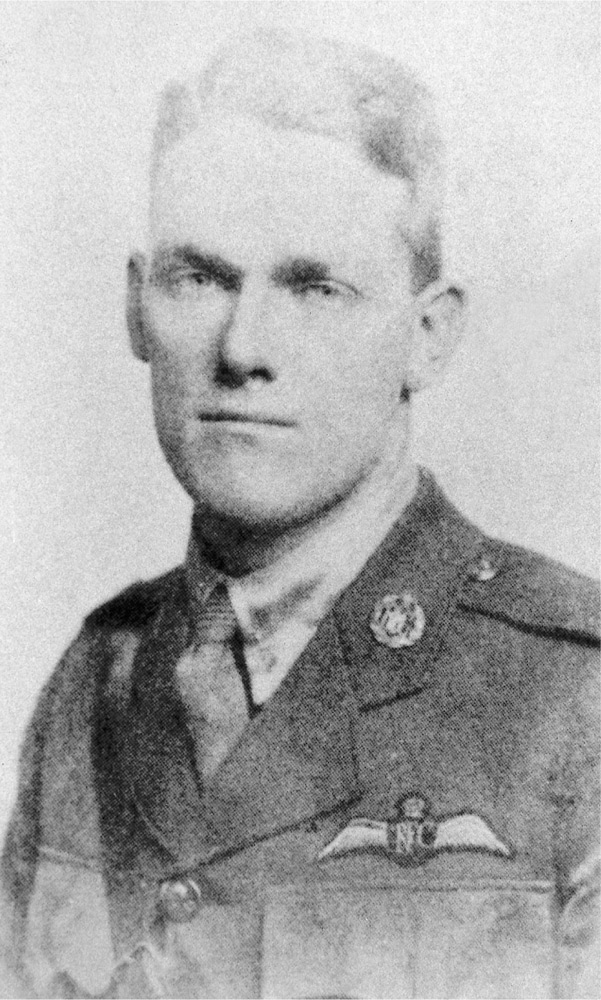

Bogart Rogers, a twenty-year-old Californian, arrived at 32 squadron in the early summer of 1918 with a devil-may-care attitude.

Rogers, a twenty-year-old Californian, wrote his girlfriend, Isabelle Young, “a petite history major with a lovely soprano voice,” whom he had wooed while they were students at Stanford University. “We have been ordered to be ready to move and have been packed for two days. Like Mohammet, if the war won’t come to us, we shall go to the war. Apparently that’s what is going to happen. If we move where we expect to we’ll get a lot of hard work.”

Rogers finished the letter, snuffed out his candle, and settled down to sleep. Minutes later he heard heavy steps on the stairs and the door to his billet was flung open. It was Major Russell. “Rogers, everything to be packed in half an hour,” barked the Englishman. “Only keep out what things you can carry in a haversack in your machine.”

Rogers did as instructed, loading his belongings with the help of his orderly on to one of several trucks. Around three in the morning the convoy departed for Fouquerolles. Russell told his pilots to get their heads down for a couple of hours. They would fly south in the morning. Rogers and his friend Alvin Callender “went up to the aerodrome, crawled into flying suits and climbed up on top of the hangars for a few hours’ sleep.” For Callender it must have been a strange moment, sleeping under the stars in northern France, almost twelve months to the day after enlisting in the RFC.

Alvin Andrew Callender was born on July 4, 1893, in New Orleans. He studied architecture at Tulane University before youthful restlessness got the better of him. Designing buildings could wait; adventure couldn’t. He joined the Louisiana National Guard’s Washington Artillery and served on the Mexican border in 1916 during the Pancho Villa hostilities. That disturbance only temporarily slaked Callender’s thirst for excitement; he craved more, and he figured enlisting in the RFC would be the quickest way to get into “a bit of a scrap.” Callender looked like a man who enjoyed a scrap: he had a strong jaw, broad shoulders, and a hard, intense look in his eyes.

Alvin Callender wrote his mother in May 1918 that he didn’t “think much” of the war.

He joined the RFC in the first week of June 1917, and trod the well-worn path from the Cadet Wing of the University of Toronto to Deseronto, “a little country town on the north bank of the St. Lawrence about half way between Toronto and Montreal.” After graduating from training, Callender was shipped out to England, and a month later, April 1918, he was posted to 32 Squadron, joining them at Beauvois (not to be confused with the town of Beauvais to the south).

Bogart Rogers’s posting to the squadron was even more precipitous. On April 23, he was writing to his fiancée from the School of Aerial Fighting in Ayr, telling her how he was playing a lot of golf to while away the hours. Five days later he was in France.

So far Rogers liked what he saw of 32 Squadron. The mess wasn’t much to write home about, “a dingy little building on a corner with ‘Au Trocadero’ in large red letters over the door,” but the men inside were first-rate. “The O.C. [Maj. John Russell] is very popular [and] the fellows seem to be far above the ordinary,” he told his fiancée. One of the fellows was an Irish ace from Belfast by the name of Walter Tyrell. He was little more than a boy, being only nineteen, but, when Rogers arrived in the mess, he was pointed out as the squadron’s top ace with ten kills. The next day Tyrell took his tally to thirteen, and Rogers, even though a year his senior, wrote home of the event with juvenile infatuation.

Rogers and Callender settled smoothly into the squadron routine, one which Rogers depicted to his fiancée in a letter home. Having first described how the squadron was on standby from 0930, Rogers wrote that often it was not until the late afternoon that they were called upon to escort a bomber squadron on a raid over enemy lines. In such a case: Major Russell briefs the pilots on the mission, ordering them to be ready to take off at 1600 hours. Half an hour before that appointed time, the ground crew wheel out the aircraft from the hangars and at 1545 hours the engines are started. The pilots emerge from the mess, where they’ve just taken tea, and walk across the grass to their machines dressed in their flying kit, talking, joking, and maintaining an air of insouciance. A last word with the squadron commander, a final check of the map, and then the pilots climb into the cockpits. He straps himself in, arranges everything to his satisfaction, checks the mascot is in place, and then runs up his motor, slowly at first, then to maximum power as a mechanic clings to each wing and a third holds on to the tail of the S.E.5.

Once the pilot is happy, his hand goes up and the blocks come out from under the wheels. The aircraft begins to taxi out to take off, waiting for the flight commander to lead them up. The rest follow in their given formation and, after a couple of turns of the airfield, the flight heads off into the sky.26

Walter Tyrell of 32 Squadron was a dashing Irish ace whose luck ran out in June 1918.

On May 16, Rogers was a member of an offensive patrol that flew south-east into the German lines. As he explained later to his fiancée, his eyes had yet to acquire the sharpness of their experienced pilots. At 14,000 feet, his flight commander, Capt. Sturley Simpson—a former British infantry officer who never took to the air without a lavender silk handkerchief in his pocket—turned due east and dived. For a moment or two Rogers was nonplussed. Then he saw six enemy fighters on the tail of a British R.E.8 reconnaissance plane. Glancing above him Rogers spotted six more Germans, “nasty looking machines with big black crosses and painted in gaudy colors.” Rogers’s flight was the meat in a Flying Circus sandwich, but fortunately for the British another flight from 32 Squadron was close on hand to spoil the enemy feast.

“The first thing that came to my mind was having been told that when a Hun was on one of your machines’ tails, open fire no matter what the range,” he wrote to his fiancée. “You probably won’t shoot him down but he’ll quickly lose interest in his target when a few bullets whizz by. So down I went motor full on, got a squirt at one little purple and white devil, and let him have both guns. In the meantime Hun tracers streaked by leaving thin smoke trails and darn near scaring me to death. I pulled out, did a climbing turn, half rolled and dived again. Just as a grand dog fight was about to start, one of the guns jammed and I pulled away. It was all over in less than a minute, for all of the Huns dived east and disappeared.”

Later on in the mess Rogers joined in the retelling of the scrap. The veterans slapped him on the back, thrust a beer into his hands, and assured him the first dogfight was always the worst. What mattered most wasn’t shooting down a Hun, but returning alive. Back in his quarters, Rogers confessed to his fiancée: “Everything happens so quickly in a scrap that one hasn’t time to think, scarcely time to act. I surely was scared blue.”

The British R.E.8 reconnaissance plane was easy meat for the German fighters.

Alvin Callender missed the dogfight on May 16. The previous day a cylinder on his engine cracked during an offensive patrol and he lost all his water through the exhaust, forcing him to crash land near Crepy. Callender spent a frustrating day badgering his mechanics to hurry up and install his new engine.

Ground crews were the unsung heroes of every squadron, described by Air Marshal Hugh Trenchard as “the backbone of our effort.” Nonetheless at every aerodrome in France there was a “them and us” attitude between the pilots and the ground crew. Pilots were officers, the ground crew were not; the social distinction was like a chill breeze sweeping the aerodrome. No fitter or rigger or armorer could ever enter the pilots’ mess and dine at the same table as a lieutenant or captain.

Nonetheless most pilots respected and relied upon their ground crew, who, in some squadrons numbered two hundred. “They carry a great responsibility,” wrote Fred Libby. “One little slip or mistake by your ground crew would be curtains for a ship, the pilot and observer.”

With the responsibility came pride. Ground crews were proud of their work, and prouder still of their pilots. Every enemy aircraft shot down was one for their own tally, just as a gun jam or a cracked cylinder was a source of anxiety. But nothing was worse than the death of a favorite pilot. “I have seen them standing out on the edge of our landing field, scanning the skies, hoping against hope that by some chance they will see their ship returning long after the time has passed when their pilot should be home,” Libby wrote.

Callender had to sit on the edge of the conversation on the night of May 16, listening to an account of the dogfight, hearing of the sharpshooting of Lt. Wilfred Green, who had shot down a Pfalz; the Albatros blasted at point-blank range by wee Jerry Flynn, a nineteen-year-old Canadian “devil,” and the smallest man in the squadron. The grandest man in the squadron was Capt. Edmond William Claude Gerard de Vere Pery, also known as Lord Glentworth, son of the Earl of Limerick. However, no one used his title in the mess: he was just one of the boys, and “a fine chap” to Bogart, who shared a room with his lordship. He was a fine shot, too, and had accounted for two Germans in the dogfight.

Two days later the Viscount went off on an early morning sortie with 1st Lt. Parr Hooper, a twenty-five-year-old from Baltimore recently arrived at the squadron. They attacked a pair of German two-seater aircraft over Etaing, but heavy and accurate fire from the observers drove them off. Hooper saw the Viscount’s aircraft go into a spin. There was no smoke, no flames, and the aircraft didn’t appear to be damaged. Hooper watched as the Viscount wrestled with his machine, struggling to bring it under control as the German ground fire intensified. Back at base the American made out his report. It was garbled and indefinite, Hooper unable to say with any certainty if the Viscount was alive, but he thought he’d seen him jump clear of the aircraft.

“Being a gentleman of some importance close enquiries were made,” Rogers wrote his fiancée a few days later. The news came back that the Viscount was dead.

Callender’s frustration grew as May deepened without his seeing any action. “After looking over this here war, I don’t think much of it,” he wrote to his mother on May 27. Despite one or two patrols a day, always well into German territory, he’d only caught sight of enemy aircraft away in the distance. They had no inclination for a scrap, “so barring unavoidable accidents, such as might happen in a street car at home, I’ll be back for a Christmas dinner in about six months.”

Callender’s luck changed the following day. This time the Germans his flight encountered “did not turn east and beat it,” but instead came to fight. There were four beneath Callender’s patrol and nine above. Another 32 Squadron patrol, led by Captain Simpson, engaged the Germans above, leaving Callender and his flight commander, Capt. Arthur Claydon, a Canadian from Winnipeg, to deal with the four Pfalz. Two escaped but two were caught, Claydon downing one, Callender the other. “I got about 75 shots into him before he turned over and fell out of control,” he wrote his mother a couple of days later. “…so this Hun is up playing with the angels now anyway instead of dropping bombs on hospitals.”