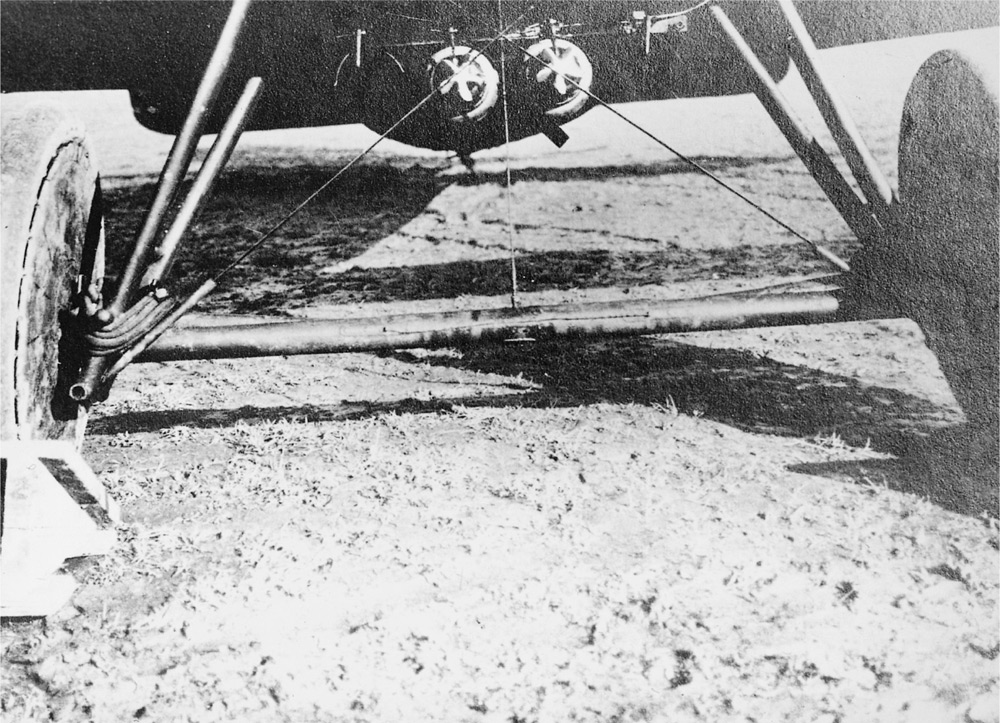

Aircraft, such as this Camel, could receive terrible superficial damage in combat and still return safely to base.

Chills Down My Spine

On June 3, 1918, 32 Squadron moved seventy miles south from Beauvois to Fouquerolles, one of nine RAF squadrons (162 aircraft in total) detailed to augment the stretched French air service struggling to cope with the latest German offensive.

Their new aerodrome was deserted when Rogers and his fellow pilots touched down. The column of trucks containing the ground crews and equipment had yet to arrive. With nothing to do Major Russell led his men into Fouquerolles. They found a small café where the owner was delighted to see airmen. Airmen meant money and soon she was serving them all “horrible wine and lemonade.”27

The move south had brought 32 Squadron closer to the war. Two nights after their arrival, there was an air raid on Fouquerolles, and, on June 5, the squadron had what Rogers described to his fiancée as a “stiff scrap” with several German Albatross. Callender had a lucky escape, said Rogers, his S.E.5 going down “for several thousand feet belching flames and smoke.…[I]t surely looked like curtains for him but he dove the fires out and came home with nothing worse than a pale face and rather shaky nerves.”

Callender made light of the terrifying incident in his own account, written to his sister on June 8. He began the letter in characteristically chest-thumping fashion. “It’s a lovely war,” he declared, before giving a flourishing account of his second victory. Set upon by an Albatros, Callender evaded the enemy fire and then turned on his assailant, already running for home. “He certainly was funny,” he recounted. “I laughed so hard I could hardly shoot because he was such a fool, he shot wild, turned and dived. I whipped my machine over as soon as I heard him, and was right on top of him with both guns going.”

Aircraft, such as this Camel, could receive terrible superficial damage in combat and still return safely to base.

As for his own brush with death, Callender had little to say. A bullet had set ablaze his fuel tank, but “when the petrol was all burnt out it went out without spreading, and I had enough gas in my tank to finish the patrol.”

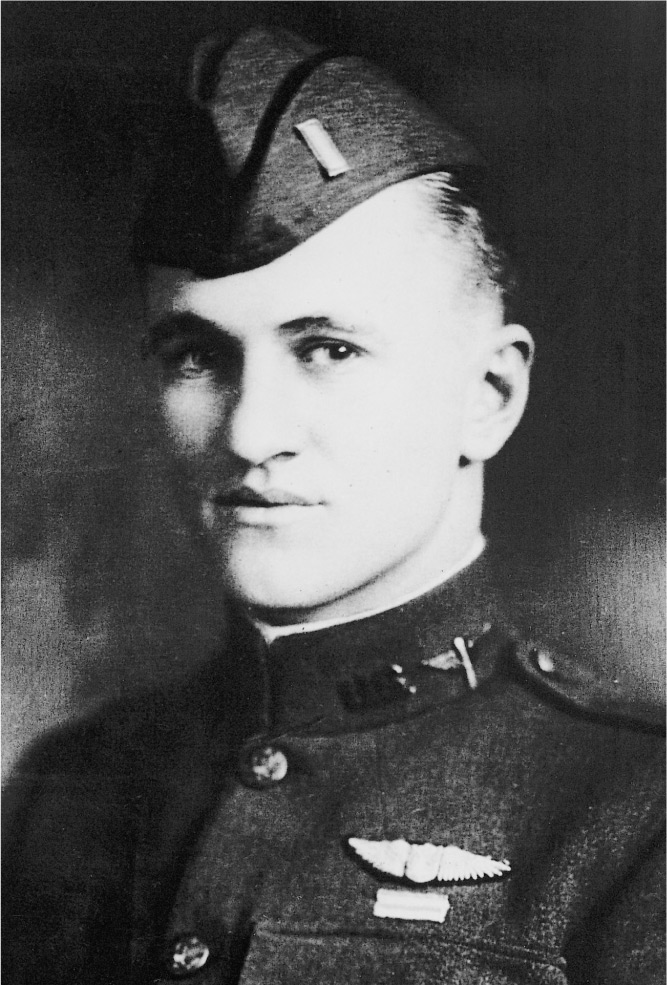

Rogers was assigned a new roommate following the death of Viscount Glentworth, a recent arrival by the name of Lt. Eric Jarvis. He was pleasant, unassuming, quiet but courteous, and at once Rogers feared for him. “Honestly, Izzy,” he wrote his fiancée. “When I wake up in the morning and look over at him, I can hardly keep from weeping. A more melancholy looking person can’t exist.”

Some pilots seemed marked for death the moment they arrived at a squadron, as if stalked by the grim reaper. More often than not they were docile men, ones who lacked the necessary aggression, even the nastiness, to survive a “scrap” or a “show” with the enemy. Others kept ahead of their nemesis for weeks, months, until finally its shadow fell upon them. Fred Libby remembered how life began draining from one of his friends in 43 Squadron. “For some reason he doesn’t seem up to par,” wrote Libby. “He seems to have something on his mind.” The pilot began to question his own ability, began asking Libby “what he has been doing wrong in his last flights.” Libby tried to reassure him that he had done nothing wrong, but to no avail. A few days later he was killed in a dogfight.

Premonitions were not uncommon among pilots. Lt. John Southey, an experienced member of 24 Squadron, recalled one June afternoon in 1918 when a mild-mannered pilot called James Dawe foresaw his own death as he sat in a deck chair. Southey and a couple of other pilots were playing a popular RAF game called bumble-puppy [the equivalent of swingball or tetherball]. “I asked him to have a game,” recalled Southey. “He refused and just sat brooding in his chair and was very quiet. He appeared to be under stress and seemed to bite his tongue as he sat there.” Dawe failed to return from a patrol the next day.

The men who coped best with the specter of death were those who accepted the odds. Nearly every pilot would crash at some stage, surmised Elliott Springs in March 1918, either by accident or as a result of enemy fire. “It’s absolutely unavoidable,” he wrote his stepmother. “Every time a man goes up he’s flirting with the undertaker and every time he makes a landing he’s kidding the three Fates about their scythes being dull.”

Celebrate life and don’t think about death, was Springs’s motto. If it happens, it happens. So, too, Rogers, who went to France a fatalist. “It was the only doctrine that would hold water,” he wrote. “If you embraced it, as many did, it was a great source of consolation. You simply decided your destiny was predetermined and inevitable and ceased worrying about what might happen to you. When your time came it would come, there was nothing you could do to stop it.”

Pilots, like these ones from 40 Squadron, tried to relax during missions, but by the summer of 1918 the stress of combat was drawing a heavy toll.

Lieutenant Eric Jarvis was returning from a patrol with 32 Squadron on June 6 when he stalled his aircraft on the approach to the airfield. The machine crashed to the ground from 200 feet and Jarvis died the same day in hospital. The death of such a callow pilot didn’t weigh heavily on the shoulders of the rest of the squadron. There was almost an element of natural selection in a frontline squadron. But three days after the death of Jarvis came the shattering news of Walter Tyrell’s demise, shot down by ground fire as the squadron strafed enemy positions near Audechy. Rogers was just one of several pilots who saw Tyrell’s aircraft smash into the ground from 1,000 feet. The next day, June 10, brought another death, this time Parr Hooper who spiraled into the ground after being hit during a bombing mission. “The short time that he was in the squadron he proved himself to be exceedingly brave and a good leader,” Major Russell wrote to Hooper’s father. “He will be a great loss to the Flying Corps, the U. S. Flying Corps, and especially to this squadron at the present time.”

Fear began to grip even the squadron’s most experienced pilots. They were no longer patrolling the sky searching for dogfights; they were strafing and bombing enemy transport, troops, and gun emplacements. It was hateful work. “Going fifteen miles over the lines at 2,000 feet, getting machine-gunned from the ground and archied all over the place is not my idea of a peaceful Sunday,” Rogers informed his fiancée. He described how he’d dropped four bombs on a road crowded with enemy troops, then swooped down to machine gun whatever he saw. “We were practically flying thru a barrage of shells, the Hun tracers streaking by uncomfortably close,” he continued. “It can’t be described. Finally after many darn good attempts archie got me and nearly ripped one aileron away, a great ragged hole that almost cut the controls and shattered the aileron.”

The explosives dropped by 32 Squadron were 20-pound Cooper bombs (which weighed 25 pounds when the explosive charge and fuse were fitted), carried on a rack under one of the S.E.5s’ wings. Each aircraft had four bombs in total and pilots released them in pairs, starting with the two on the outside. Upon release the “nose spinner was freed to turn which then rotated a plate in the nose, which eventually exposed the detonator to a firing mechanism, which would be activated when the bomb struck a solid object.”

British fighters carried 25-pound Cooper bombs for low-level bombing missions.

On June 9, Callender’s six-strong flight bombed an anti-aircraft battery east of Roye, but only two aircraft returned to base. No one was killed, but it was indication of the perils facing the squadron. Callender had been forced down by a broken propeller, a problem that was soon repaired so he was able to participate in an afternoon offensive patrol. In the evening the American was in the air again, on a bombing mission led by Major Russell himself. Callender dropped bombs on an A.A. battery near Faverolles and avoided the ferocious ground fire directed his way.

There was no rest for Callender. The next day, he and Claydon bombed another gun battery, only this time a flight of enemy aircraft was lying in wait among the clouds. Four Fokker D.VIIs went after Claydon; the other four targeted the American. Then nine more came into view.

The Fokker had entered service two months earlier, the most recent addition to the German air force and rated by Manfred von Richthofen as a brilliant fighting machine. He’d tested the prototype in January 1918 “and was so enthusiastic that he delayed reequip-ping his J.G.1.” A biplane of cantilever wing design with no external bracing, the Fokker D.VII was powered with a 185-horsepower BMW engine, could hit 130 miles per hour in level flight, and was capable of climbing to 13,200 feet in ten minutes.

The S.E.5s turned tail and fled for their lines, chased all the way by the Fokkers. Callender later counted eight bullet holes in his fuselage and one in his engine. “I hope my luck keeps with me,” he wrote to his mother two days later.

The low-level flying eased slightly in the days that followed. There was time to sit in the sunshine, gorging on strawberries and cherries. Some pilots challenged each other to games of tennis on an improvised court, others went into town and got drunk on cheap wine. Rogers and Callahan wrote letters home, reveling in their sudden “sweet slumber.” Callender told his mother he found the war “an interesting diversion with its enjoyable points.”

On June 28, the squadron moved north again, this time to an aerodrome at Ruisseauville, approximately twenty miles south-west of 85 Squadron at St. Omer, which they shared with a squadron of bombers. If the rumors were true, the Germans were about to launch a big offensive in Flanders.

The Fokker D.VII had a 185-horsepower BMW engine, could hit 130 miles per hour in level flight, and was capable of climbing to 13,200 feet in ten minutes.

However, there was no offensive, at least not in the first week of July. Callender found time to read an English translation of von Richthofen’s memoirs, The Red Battle Flyer, and Springs wrote a long letter home about the number of popcorn vendors in Los Angeles: thirty-two, of whom twenty-nine were Italian. On July 4, the squadron threw an Independence Day party for its two Americans, a lavish affair with the mess decorated in red, white, and blue and draped with a Stars and Stripes. The menu consisted of crab salad, soup, fish, chicken, cauliflower, asparagus, strawberries, nuts, and coffees, “to say nothing of liquid refreshment.”

The airmen were still partying at two in the morning and one or two of the abstemious pilots wondered what would happen if orders came through for a dawn mission. But dawn on July 5 rolled back to reveal thick cloud. God was clearly an American, said Rogers, who, like everyone else, slept until noon.

The von Richthofen brothers, Manfred and Lothar, are in the center of this group of Circus pilots.

Three days later, July 8, Callender shot down his third German, a Fokker D.VII, though another “sent streams of lead past my ear and chills down my spine.” Rogers was still searching for his first victim but instead found himself detailed to chaperon several new pilots on an afternoon patrol. He found it an irksome assignment, mollycoddling three novices when he was desperate to join in a dogfight below. At one moment he spotted three red Fokkers “sitting at about our level and east of the scrap.” The two enemies observed one another, cruising “around and around.” Were the Germans also there for the experience, or were they trying to lure the four British aircraft into a trap? Springs suspected the latter and kept his young charges under his wing.

On July 9, Callender got into another scrap with the Germans, one that cost the life of his flight commander, Arthur Claydon. Casualties were mounting, but replacements were arriving, one of whom was another American, John Donaldson, from Fort Yates, North Dakota. The son of Gen. Thomas Donaldson, the twenty-year-old was a graduate of Cornell University and a confident pilot who arrived at the squadron on July 3. He didn’t have long have to acclimatize to his new surrounds; on July 14, 32 Squadron moved two hundred miles south to Touquin, a town on the Marne, east of Paris, where perhaps this time the great offensive might unfold.

They were ordered to carry out low level attacks on the Marne bridges and strafe enemy troops and artillery. Every heart in the squadron sunk, except Donaldson’s, who had yet to become acquainted with the terror of low-level flying. On July 22 he scored his first victory, a Fokker D.VII shot down over Mont Notre Dame, the same dogfight in which Rogers finally got his name on the squadron scoreboard.

Some in 32 Squadron found John Donaldson brash, but all admitted he was a brilliant pilot.

It had been a hell of a scrap, Rogers wrote his fiancée, erupting as they escorted a squadron of bombers on a raid over German positions. The dozen Fokkers hadn’t spotted the S.E.5s flying above the bombers and they had “tumbled down on them like a load of bricks.” Two “particularly gaudy” Fokkers caught Rogers’s attention and he singled out one, giving him a couple of “good bursts at close range.” The machine turned on its back, its pilots doomed to an appalling death. All in all, four Fokkers were downed, cause for celebration had it not been for an incident on the way home. One of the bombers took a direct hit from an A.A. battery. “It went down a mass of flames,” wrote Rogers. “Not a pretty sight, especially as one of the chaps jumped out at about 12,000 ft.”

It rained throughout July 23, one of those wet summer days that feel like February with the cloud so low one could almost reach up and touch it. The members of 32 Squadron decided on a whim to head into Paris in a seven-passenger Packard and live it up for the night.

It was one of the incongruities of a combat squadron; the ease with which they could replace austerity with comfort and forgo terror in favor of gratification. First the eight pilots dined at Maxim’s, then they went to the Casino, which Rogers described as a “sort of combination theatre-café.” Afterward, they strolled through the streets of Paris, marveling at the women, and telling each other that while the air war could be hell, it was still a darn sight better than life led by the “Poor Bloody Infantry” in the trenches.