Anti-aircraft fire was rarely fatal, but it could cause a lot of superficial damage to aircraft, as seen from this shredded upper wing.

Why Are You Crying, Sir?

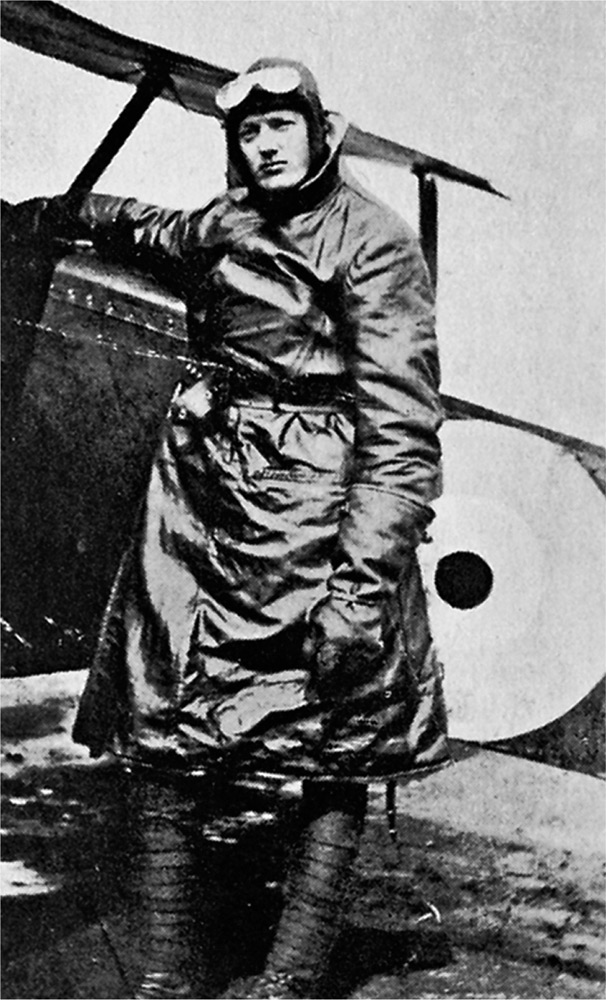

There was still no news of John McGavock Grider forty-eight hours after his failure to return from his patrol. Since his anguished entry in his diary the night of his friend’s disappearance, Elliott Springs had convinced himself all was well. In a letter to his stepmother dated June 20 he wrote: “I imagine his motor cut out. I don’t think Archie could have gotten him—I saw no Huns about—and I think I killed the observer so I don’t believe Mac got hit [during the attack on the enemy aircraft].…I feel sure that Mac is personally safe wherever he has landed. He’s a prisoner all right but no one knows how I miss him. No man ever had a truer friend, and the fact we fought together and in unison and harmony shows the confidence we had in one another.”

However, with each day that passed, Springs’s hope receded. If Grider was a prisoner, word would reach the squadron, more often than not dropped on the aerodrome by a single German aircraft. But no messages fell from the sky. One message did arrive at the Grider plantation in Arkansas, delivered into the hands of John’s father. It ran: “Lieutenant Grider reported missing in action June 18, 1918.”

Springs contacted the Red Cross but they had no record of a John McGavock Grider; undeterred he arranged for the charity to send Grider some food parcels the moment they learned of his prison camp. Mac wasn’t dead, Springs was sure of it. Anyone but Mac.

The Red Cross finally contacted Springs at the end of July. They had news from the Germans: a body had been identified as John McGavock Grider. The confirmation devastated Springs. He told his father about it in two short sentences, each one shackled by suppressed emotion. It was left to Captain B.A. Baker to write Grider’s two children:

My Dear John and George:

I am writing to you to tell you of your father, who came out to France with us and who one day after flying for a long way over into the enemy’s country, I am very sorry to say did not return; and whom, I am more sorry to tell you, neither you nor I will ever see him again. Your mother will read you this letter and I dare say there are many things in it you will not understand; but she will keep it for you and later you will be able to realize it more, and you will be able to see how fine a man he was. We came out to France in the middle of last May, a new squadron under a very famous leader. The pilots were carefully chosen and with us came three Americans, one of whom was your father. All of them were very keen and none more so than he. He was always cheerful and always out to hunt the Germans. He had several fights and with two or three other pilots helped to drive down several enemy machines. And then one day he went out, a cloudy day with a strong wind blowing from the west—blowing our machines over toward Germany. And he saw an enemy machine—a two-seater high up in the sky and about fifteen miles over. With another pilot he immediately made fast, keen only on bringing it down. They soon closed in on it and, after a short fight, down he shot the German. And then they both turned to come home, battling against the strong wind. After some time the guns from the ground opened fire, and the other pilot (also an American called Springs) lost sight of him and thought he was following, for it is often difficult to see other machines in the air. He (Springs) came home, but there was no sign of your father; we waited, hoping he had landed somewhere, but no news came, and we were forced to give him up as missing and could only hope that he was at least alive and a prisoner. But we were glad for a time that before he was lost he had brought down the German. Days went by and we hoped for news. And then one day it came through that he had fallen behind the enemy’s lines. I can-not tell you how sorry we were, for we had lost a very great friend, a fine pilot and a very brave soldier. And you will hardly realize the greatness of your loss, but you will remember enough of him, and your mother will tell you of him, so that you will turn out in later years as fine men as he was; and you will remember with pride how nobly he fell in the war, which I hope by the time you are grown men will be finished once and for all. And so now I will say goodbye to both of you, hoping that you will cheer up and cheer up your mother too, because, like you, she too feels very sad indeed and it is up to you to try to help her forget her sadness. And so goodbye.

[Signed] B. A. Baker, Captain.

Grider’s loss wasn’t the only one endured by 85 Squadron in June 1918. Billy Bishop was recalled to England in the second half of the month at the request of the Canadian government. His luck couldn’t last, they reasoned, if he kept hunting Germans on a daily basis. Sooner or later he would be shot down, and Canada wanted living heroes, not dead ones. He was ordered home to help organize the new Canadian Flying Corps. “This is ever so annoying,” he wrote to his wife.

The squadron gave Bishop a send-off to remember. Springs was to the fore of the celebrations, as assistant mess president and “representative of Bacchus.” Dinner was filet of sole, broiled chicken, and fresh peas, followed by strawberry ice cream, camembert, and coffee, all washed down with several bottles of wine of an excellent 1906 vintage.

With no Bishop and his replacement as squadron commander, the noted ace Mick Mannock, yet to arrive at St. Omer, Springs flew with less restraint than ever. On June 25, he spotted a German two-seater east of Kemmel. Springs left his patrol and dived on the enemy aircraft, confident this “cold meat” would take only a minute or so to destroy. “Not so,” he wrote his father. “I had picked the wrong Hun.” His adversary was, in RAF slang, “a stout fellow,” and for several minutes the two aircraft dueled. “Just as I was about to open fire the Hun turned sharply to the left and I was doing about 200 [mph] I couldn’t turn,” wrote Springs. “So I pulled up and half rolled and came down on him again. He turned up to the right and forced me on the outside arc giving his observer a good shot at me as I turned back the other way to cut him off from the other side.”

For a second Springs was the cold meat. If the observer had been good he would have dealt the American a fatal blow. But his shots went wide, and in an instant Springs pulled up, half rolled, and opened fire from above and behind. Still the German pilot tried to atone for the incompetency of his observer with a deft piece of flying: he stalled, side-stepped Springs, and allowed his gunner a second chance to end the fight. But Springs also had a clear shot and his burst hit his enemy’s engine. The German was now in serious trouble—cold meat. He put his machine into a spin in a desperate attempt to escape his assassin. Springs followed him down, “firing at him from every conceivable angle and [I] even got so exasperated that I threw an ammunition drum at him.”

The rest of the British patrol arrived to join in the kill, sending a “steady stream of lead into him.” Springs turned away from the destruction at 1,000 feet. It was no longer fun. The pilot had deserved better.

Two days later Springs was out again on patrol, accompanied by Captain McGregor and a newcomer to the squadron, Lt. Donald Inglis. They encountered a German two-seater east of Bapaume, this time crewed with an observer who knew how to hit the target. McGregor led the attack, overshot, so Springs seized the initiative in feverish pursuit of that all-important fifth victory. He came “in close from an angle and got under him.” His pressed his trigger finger but nothing happened. He pressed it again. Nothing. He became aware of tracer fire lacerating his wings, “like wood fire crackling, only more so.”

Then his oil pressure went dead. “There was nothing to do but try and glide back to the lines,” he recalled. As Springs slid slowly down from the sky, German anti-aircraft batteries opened up, and as he came nearer to earth, infantrymen joined in the fusillade with rifles and pistols. Springs even saw one soldier hurl a tin can in his direction. Then he saw the ground coming up, faster and faster. He covered his face with his hands and braced for the impact.

“Why are you crying, sir? You’re back home.”

It took Springs a few moments to recalibrate his senses. The voice wasn’t German, it was definitely English. The American pointed to his mouth and gibbered, “My teeth! They’re all gone!”

“No they’re not, sir,” said the British soldier. “Here they are.”

He reached a hand inside Springs’s mouth and pulled back his lips from his teeth. A field dressing was applied to the hole in his chin, and soon a padre arrived to pour cognac down his throat. By evening Springs was a patient in the Duchess of Sutherland’s hospital in St. Omer, clad in the red silk pajamas that he’d had on under his flying suit.

Anti-aircraft fire was rarely fatal, but it could cause a lot of superficial damage to aircraft, as seen from this shredded upper wing.

McGregor and Larry Callahan arrived at his bedside the next day, relieved to learn that apart from the hole in his chin, their comrade had nothing worse than a concussion. Callahan handed to the patient a “crocus sack full of champagne and we had a binge.” As they drank, Callahan promised he’d collect Springs’s replacement S.E.5 and fly it back to base so it would be waiting for him as soon as he returned to the squadron.

Captain Malcolm McGregor of 85 Squadron was a friend to the Three Musketeers.

However, when Callahan next visited Springs, he found his friend in a foul temper, cursing at a telegram he clutched in his hand. Springs had been appointed a flight commander in the 148th Aero Squadron, one of two all-American squadrons, 17th Aero being the other, attached to the RAF. “I want to stay with 85,” Springs complained to Callahan, “where I am reasonably sure of getting some Huns and where all is going well.”

A Flight of 148th Squadron: Wyly, Rabe, Kindley, Knox, and Creech.

Springs told Callahan he’d been on the phone to RAF headquarters to argue his case, only to be curtly informed that “I wasn’t doing the appointing this season.” Callahan suggested Springs should cable Washington to request the order be rescinded. It was a neat idea but it would take too long. They both knew how slowly the wheels of military bureaucracy turned. “It looks like I’ll have to go [to the 148th Aero] though I can’t figure why they would yank me away from 85 like this after all the trouble Major Bishop and Capt. Horn took to get me.”