Lieutenant George Wise of 148th Squadron. Library of Congress

I Am an Old Man

At the 3rd Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun, two hundred miles south of 32 Squadron’s base at Touquin, Lt. Arthur Taber wrote his father a long letter on July 7. He had been at the center three months and wanted his father to know why his aviation career appeared to have stalled. It was all because of his initial decision not to train as a fighter pilot. “I have analyzed minutely my attitude on this question and have come to the conclusion that my decision is based upon prudence and not upon cowardice,” stated Taber. “I am certainly not afraid to go out as a chasse [fighter] pilot; on the contrary, it is so alluring a career that it would be easy to do; but my feeling is that it is my duty to gain all the experience possible so that I may later on be a better chasse pilot than now, and thus save for the government a pilot and his plane.”

To validate his point, Taber chose the “striking example” of some of his classmates from Oxford. While there, he “lived with some Americans—all perfectly fine chaps and crazy to go chasse, like everybody else. Eighteen of them went to the front, and in six weeks there were six left. The fault was not with them, for there could not have been finer men, but they were not sufficiently experienced for such a tough job as chasse fighting. Three of them dived on one Hun machine with the result that they all collided and were killed, their planes utterly smashed, and the Hun escaped.”28

Taber had hoped to become a reconnaissance pilot, but, he told his father, he was reconsidering. He was concerned that if the Germans should develop a “a plane which can overtake and shoot down the now supreme reconnaissance planes, I shall not be so keen upon going out on the latter type.” Therefore, Taber said, he was having second thoughts about becoming a fighter pilot and might perhaps undertake the training after all.

Alas, a day after writing the letter, Taber was hauled out of flying school and assigned to duty as a transfer pilot. Not that he was crestfallen at the collapse of his ambition to fly fighters. It was, he declared, “the most extraordinary piece of good luck,” and to cap it all he was based just outside Paris. As he told his father, he was now “contributing materially to the success of the present allied effort by keeping the squadrons at the front supplied with new planes.”

Elliott Springs had also been busy writing letters. Time had been “hanging heavy” as he lay in the Duchess of Sutherland’s hospital in St. Omer recovering from concussion and waiting for the wound in his chin to heal. He was also coming to terms with the fact he had but no choice to comply with the order instructing him to join 148th Aero Squadron.

On June 28, he propped himself up in bed and composed a long letter to Maj. Harold Fowler, liaison officer between the British and American forces. It was Fowler’s job to best integrate the two all-American squadrons within the RAF, a role he doubtless found mundane given his experience as a combat pilot.

Born in Liverpool, England, in 1887, Fowler’s family had moved to New York when he was a boy but he retained a strong sense of his British identity. After a spell working in the New York Stock Exchange, Fowler was appointed in 1913 as secretary to Walter Hines Page, the U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain. Within two years, however, Fowler was serving in the trenches as an artillery officer, but, like so many junior officers, the allure of the airplane proved too strong and he soon volunteered for the RFC. He flew combat missions throughout the “Bloody April” of 1917, earning a Military Cross for his “conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty.”

However, as soon as the United States entered the war, Fowler applied for a transfer, and his experience was put to good in the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. On May 18, 1918, he replaced Maj. Thomas Bowen as liaison officer, an inspired appointment that proved of enormous benefit to the incorporation of the 17th and 148th Aero Squadrons into the 65th Wing of the RAF.

Lieutenant George Wise of 148th Squadron. Library of Congress

“He therefore understood better than many Americans the possibilities and the difficulties of British organization,” wrote Lt. Frederick Mortimer Clapp, the 17th’s adjutant. “He saw, as no one before him had in the slightest degree tried to see, the necessity of seconding us in the desire we entertained of making our relations with the British happy and friendly.”

Fowler was like no other liaison officer. He used his own Sopwith Camel to fly from airfield to airfield, seeking out the American pilots flying with RAF squadrons, and allowing him to indulge his love of flying. It was a thankless task for much of the time. Not only were many of the pilots unhappy at being uprooted, but so were the squadron commanders who, by the summer of 1918, held their American pilots in the highest regard. They were, as one squadron noted, “the flower of the American fighting stock.”

In Springs, Fowler knew he had one of America’s finest combat pilots; wasn’t that why Captain Morton Newhall, 148th’s commander, had been adamant he wanted Springs in his squadron?

Fowler might very well have flown his Camel when he came to visit Springs in the Duchess of Sutherland’s hospital, depositing some candy by his bedside, and then asking him to produce a memorandum on the principles of aerial combat.

The result was a detailed document that was as much an eulogy to 85 Squadron as anything else. Under Major Bishop, wrote Springs, they “worked on the principle that a scout patrol was ordered to perform a definite duty and this duty would be performed best by sticking closely to the job in hand and not by wandering about the skies indiscriminately in search of EA.”

Springs’s memo was surprisingly coherent considering his head was still heavy with concussion. His advice was just what Fowler wanted, pearls of wisdom to pass on to the inexperienced pilots.

• It is foolish to fight EA Scouts except when it is possible to start the fight from above.

• If the patrol leader does not lead the patrol down, individual pilots should not attack on their own.

• Great care should be taken in the morning when the sun is unfavorable [rising in the east, into the eyes of the RAF]. If you cannot attack with the advantage, don’t attack.

• Daring without skill is not an asset but a serious menace.

Springs was released from the hospital the day after writing his memo, but instead of heading to 148th, he hitched a ride back to 85 Squadron and pleaded one last time to remain with them. But there was nothing anyone could do. The appointment was official; he was now the commander of B Flight, 148 Aero Squadron, based at Capelle, three miles south of Dunkirk.

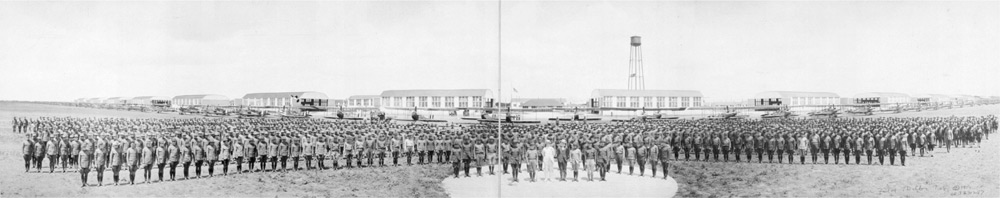

Young American recruits at one of the Texas training fields, circa 1918. Library of Congress

He arrived at his new base on the July 1, probably having been filled in by Fowler on the squadron’s history. Formed the previous fall, the 148th did their initial training at Fort Worth, Texas, a base that had been laid out to British specifications. As a Texas newspaper, the Bonham Daily Favorite, explained in its edition of August 8, 1917, an official communique had been issued the previous day, which stated that Lt. H. B. Denton would be responsible for overseeing the construction of the training facility. “This camp in Texas will mean still closer cooperation between the aviation societies of the American and British forces and a further standardization of work,” said Denton. “The plan is to reproduce in Texas aviation schools like those of Camp Borden.…[A] large number of the cadets recruited in New York will be sent to Texas to finish their training.”

Fort Worth consisted of three fields to the north, south, and west. Locals knew them as Hicks, Benbrook, and Everman but the cadets designated them Camp Taliaferro, Field Nos. 1, 2, and 3. Flying conditions in Texas presented a particular challenge to the cadets, as in the Lone Star State the air was “much dryer and less buoyant [than in Europe]. Calm air was the exception, despite the comparatively flat country.” In addition the temperature range at Fort Worth was extreme with the arrival of the “blue norther,” a Texas phenomomen in which a fast-moving cold front causes temperatures to plummet, sometimes, as was the case in 1918, from 70 to 20 degrees Fahrenheit in a couple of hours.

On February 24, 1918, two days before the 148th shipped out to England on board RMS Olympic, the Galveston Daily News ran an article about Fort Worth. It began with a declaration that “the American youth has a natural aptitude for flying,” and that over the winter the cadets in Texas “have proved almost startling to instructors from the allied armies who are here to give the Americans the advantage of their experience and knowledge.”

Nonetheless such proficiency had a price, continued the paper, noting that the death on February 23 of Franklin Fairchild of Pelham, New York, brought to forty-seven the number of the cadets killed since Fort Worth began training recruits in October 1917. This was forty more fatalities than the American-run training facility in Houston, and the Galveston Daily News was curious to discover why Fort Worth, with its veteran British and Canadian instructors, should have racked up so many fatal accidents. An officer cadet explained that: “[t]he British theory is that the men should receive early instruction in all the difficult work they will have to do in actual service while the American trainers spend a larger part of their time in drilling the fundamentals of flying.”

While American cadets flying under American instruction were forbidden from diving and looping and half-rolling, the British instructors had no such qualms about ordering their charges to perform such maneuvers. Partly this was because they were not subject to American military discipline and could not be punished for breaches of procedure, but also it was because the British and Canadian instructors were combat veterans. In the skies over France they had learned the hard way that the theory taught in warm classrooms by well-meaning but untested instructors was irrelevant in a dogfight. They preferred practical instruction, regardless of the danger that entailed.

After spending two weeks in England, the 148th arrived in France on March 17, 1918, and for the next few weeks shadowed 40 Squadron RAF “to learn something of the maintenance tasks involved in keeping a flying squadron airworthy.”

Springs’s chagrin at being plucked from 85 Squadron diminished when he arrived at Capelle and saw some familiar faces—men he’d last seen at Oxford, what now seemed a lifetime ago. These included Kent Curtis, Bill Clements, Linn Foster, and John Fulford, not to mention Henry Clay, and Bennett Oliver.

Kent Curtis was one of the Oxford cadets who later transferred to 148 Squadron.

Oliver was the son of a former senator of Pennsylvania whose first trip in an airplane had been a Thanksgiving joyride in 1916. Climbing out of the Curtiss Jenny cockpit on Governor’s Island after a flight around New York, Oliver exclaimed: “This is for me!” In May 1917 he began flight instruction, and three months later he was one of the fifty-two cadets aboard RMS Aurania under the command of Capt. Geoffrey Dwyer.

He had been one of the handful of Americans posted to 84 Squadron in May 1918, and over the course of the weeks and months that followed he’d learned much about the war in the air. The majority of German pilots, he believed, were short on “initiative and guts.” He told his new comrades in 148th Squadron that he had “never had a fight on our side of the lines” because the enemy were too scared to cross into enemy territory. Bennett was also dismissive about the German aircraft; although he admitted the Fokker D.VII was good, the Albatros lacked agility because of its “heavy slow speed and six cylinder engine,” and the Pfalz was “pretty slow.” He did admire the Germans for one thing, though: “they used smoke tracers which left a trail so that if you saw the shots go to the left, you simply turned to the right and vice versa.” Oliver (“Bim” to Springs) was appointed leader of A Flight, Henry Clay took responsibility for C Flight, and Springs was in charge of B Flight.

Henry Clay was another Oxford cadet.

Just as he was getting to know his new squadron, Springs fell ill. It was, he wrote home a fortnight later, a combination of factors: a toxic mix of “whiskey, brandy, anti-tetanus serum, and morphine.” Nothing to worry about, though, even if his eyes were bad and his joints swelled up to twice their size. Larry Callahan dropped in to see his fellow Musketeer, filling Springs in about his second victory and about life in 85 Squadron. Springs wanted all the news, and listened agog as Callahan told him they’d shot down twenty Germans since the beginning of July for the loss of just two men. “It makes me sick to think what I’ve missed,” Springs wrote his father.

Discharged from hospital on July 19, Springs was sent on leave to Paris for a few days, but he spent most of the time feeling like “a ham sandwich at a banquet.” He ate well, and drank much, but neither activity brought him much joy. He stared listlessly at the beautiful women gliding along the sidewalks of the French capital, but they too failed to arouse much interest. His thoughts were at the front. He wanted to be back with the boys; that’s where he was happiest. He sat at a café and wrote to his stepmother. “I am an old man,” he began. “The mirror shows no white hairs but mental reflections shows unmistakable signs of old age.”

He was back with the 148th by the end of July. “I feel much better,” he told his stepmother on July 30, the day he was chased home by a couple of Fokkers. However, he still clung to 85 Squadron like a child to its mother’s apron strings. He phoned Larry Callahan each day, congratulating his friend on taking his tally to four. But there was also bad news. The squadron’s new C.O., the great British ace, Mick Mannock, had been shot down and killed.

The next day, July 31, Springs celebrated his birthday. Callahan and Spencer Horn flew up from 85 Squadron for a birthday lunch and they spent much of the meal discussing the dead. Springs learned that Mannock had died in the way he’d always feared—shot down in flames—and Callahan brought confirmation that Grider’s remains had been formally identified.

Springs was now twenty-two, but there were days when he felt twice that age.