Jesse Creech was one of the first eight recruits to the 17th Squadron in 1917.

The 17th Aero Squadron

For such an unprepossessing individual, Orville Ralston had a rare distinction. He had been among the eight Canada-trained aviators who marched into Fort Worth on October 17, 1917, the first recruits into the 17th Aero Squadron.

Ralston was from Nebraska. Born in September 1894, he graduated from the Nebraska State Normal School (now Peru State Teachers College) and was in the second year of studying dentistry at the University of Nebraska when he decided to enlist. Ralston was stout with protruding ears and wavy brown hair. At university he answered to the name of “Wob” on account of his wobbling walk; in the military he was “Tubby.”

Ralston’s formative years had been quiet and unexceptional; he’d been one of those boys content to stay in the background, undistinguished and unnoticed by many of his peers. However, that changed when he was among the first Aviation Corps recruits to be transferred to the RFC in Canada.

Upon arriving in Toronto, Ralston wrote home: “It seemed rather strange to be the first ‘Yanks’ in Canada. I know I felt embarrassed at the way in which we were watched by the cadets as well as the public in general.”

Ralston was a natural pilot. On the ground he had an uneven gait, but once in the air he flew his machine with a singular smoothness. He was appointed commander of Flight C of the 17th Squadron when they began flying at Hicks Field, and in his letters home he described how he was growing accustomed to his newfound status. “People in Texas had never seen airplanes before,” he wrote in his diary. “Hundreds would come out, flock around the machines, whenever we would land near a town. Often we had meals out and met many swell girls.”

The hospitality of Fort Worth citizens toward aviation cadets became legendary. They subscribed $75,000 “to provide funds for the local branch of the American War Service Board, and rented a large club room and dancing hall in the center of the city, where comfortable accommodation was found for men of both the American and British services.” The town’s assorted ladies’ clubs organized dances and the Fort Worth branch of the Y.M.C.A. “saw to it that commodious huts and writing rooms were furnished.”

Jesse Creech was one of the first eight recruits to the 17th Squadron in 1917.

Ralston committed the name of the first eight cadets in the 17th to his diary: as well as himself there were Walter Jones, Ralph Gracie, Charles France, Ralph Snoke, Oliver Johnson, Harold Shoemaker, and Jesse Creech. They were soon joined by another eight recruits, and throughout the rest of the fall more young men arrived in Texas.33

Ralston was commissioned first lieutenant on December 31, 1917, nine days before the 17th Aero Squadron shipped out to England on board the Carmania, the same vessel that had conveyed the Three Musketeers to Europe four months earlier.

The 17th Aero Squadron arrived at an RFC rest camp at Romsey, Hampshire, in the south of England, radiating pride. They considered themselves the elite of American aviators; however, to the British, they were just fresh meat. “17th is split up,” wrote Ralston in his diary on February 19, as dismayed as the rest of the squadron at their fate. They had enlisted together, trained together, and they wanted to fight together, but the British had long since dispensed with military sentimentality.

The Americans were ordered to France, and once there the British cleaved the squadron, assigning Headquarters Flight to 24 Squadron at Martigny; A Flight to 84 Squadron, at Guizancourt; B Flight to 60 Squadron, at Sainte-Marie-Cappel on the Flanders front; and C Flight to 56 Squadron at Baizieux.

For the first few months in France “the flights were totally out of touch with one another,” recalled 1st Lt. Frederick Mortimer Clapp, who replaced Lt. Henry Bangs as squadron adjutant in the spring. The initial disquiet of the Americans at their treatment soon vanished when they realized this was all part of their instruction, and far more productive than attending some tedious flight school in Scotland. They were, wrote Clapp, “most exciting times” and the “men of the 17th Squadron learned much more than the mere care of their machines. They knew now what it meant to send out patrols and move incessantly from one aerodrome to another at the same time.”

Orville Ralston was absent from this invaluable schooling. Since he was one of the squadron’s ablest pilots, he had been kept behind in England to learn how to fly bombers. To Ralston it felt like a punishment. He wanted to fly fighters, and he confessed to his diary that he was “rather discouraged” at the unexpected turn of events. He began flying bombers—the DH.4 and “the deadly DH.9” (deadly to the pilots not the enemy on account of its unreliable engine)—and kept alive his dream of flying into combat inside a Camel or S.E.5. However, the news from France deepened his gloom. In June the 17th Aero Squadron began to reassemble at Petite Synthe aerodrome, recently vacated by Maj. Billy Bishop’s 85 Squadron. On June 21 the squadron—assigned to the RAF’s 65th Wing under the command of Lt. Col. Jack Cunningham—appointed as its commander Sam Eckert, who had performed well with 84 Squadron. Eckert’s three flight commanders, in charge of A, B, and C respectively, were Mort Newhall, Weston Goodnow, and Lloyd Hamilton.

Hamilton was notified of his appointment on June 20, and a day later he arrived at Petite Synthe accompanied by Lt. Bill Tipton. Between them, while serving with 3 Squadron, they had shot down seven enemy aircraft in two months; Hamilton accounted for five to make him the first of the 150 “Warbirds” to become an ace. Tipton was soon promoted to take charge of B Flight, while Goodnow became A Flight commander in place of Newhall, appointed commanding officer of 148th Squadron.

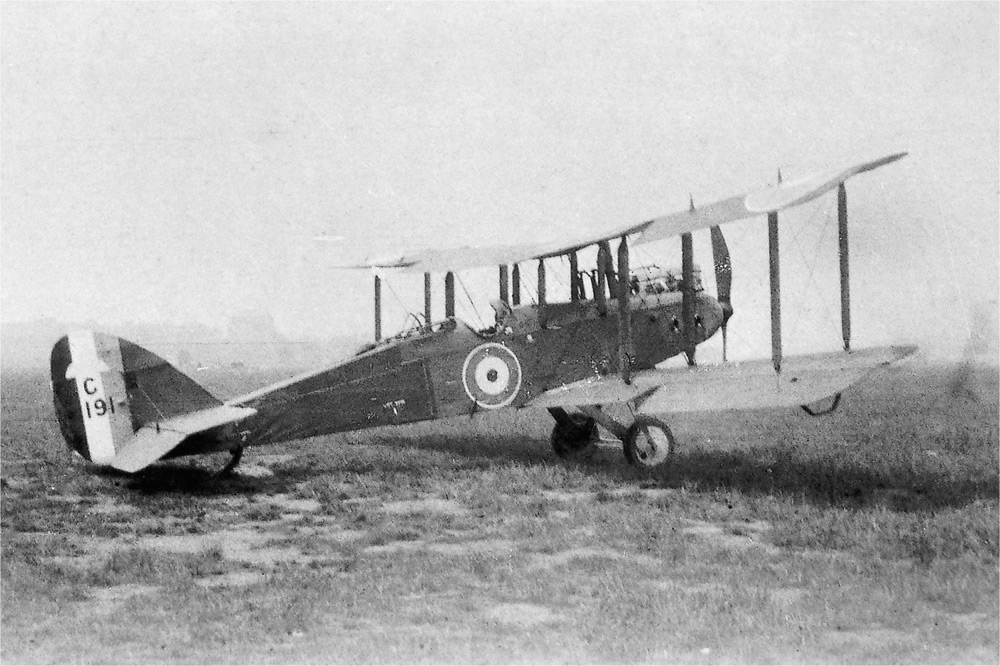

The DH.9 bomber was nicknamed “deadly” to British pilots on account of its unreliable engine.

Many of the pilots serving in the three flights had been shipped out with the 17th Squadron in January, including Ralph Gracie and Ralph Snoke, two of the cadets who had arrived at Fort Worth with Ralston. Others came “from the Training Brigade through the pool from which all British trained pilots were drawn.”

However, a squadron of combat novices wouldn’t survive long, so a nucleus of experienced pilots were transferred from the RAF squadrons they’d been flying in for months. Lieutenant Frank Dixon recalled that, on June 25, after scarcely a month with 209 Squadron, he and three fellow Americans were ordered to leave for 17th Aero Squadron. Henry Frost arrived at Petite Synthe from 210 Squadron, with whom he’d been flying since April 2; Merton Campbell turned up looking lost, bemused as to why after nearly four months of loyal service with 54 Squadron he’d been so abruptly uprooted.

To guard against the growth of resentment among his combat veterans, Sam Eckert adroitly nurtured an espirit de corps in the new squadron. An insignia was designed, “a white dumb-bell painted on each side of the fuselage aft of the cockpit” carried on all the 17th Squadron’s 114 Sopwith Camels.34

Eckert also dispatched some personnel to the Channel port of Calais to buy luxuries for their quarters at Petite Synthe. They returned laden with “all the light-green iron garden chairs the Nouvelles Gaieties of that place possessed.…[W]icker chairs and cushions were bought too.” Prints and pictures were hung from the walls of the mess, a piano was procured, along with a gramophone, and a stack of records, including Grieg’s “Asa’s Death” and the “Song of the Boatmen on the Volga.”

Eckert also insisted that although the 17th was an exclusively American squadron, and proud of it, it would honor the influence of its ally. “British-trained, we retained their customs at mess,” reflected Frank Dixon. “Dress without Sam Browne belts and waited for the C.O. to test the soup, although we failed to pass the port and drink to the King after dinner as the British did.”

Frederick Clapp, the 17th’s adjutant, recalled that the mess was a riotous place, reverberating with laughter most of the time as the pilots gleefully waited for some unfortunate pilot to arrive at dinner wearing his belt, or to light up a cigar before Eckert had a put a match to his own. “Nothing brought forth such peals of merriment as the infraction, through thoughtlessness, of any of our rules,” wrote Clapp. “The offender bought drinks or cigars or both all around, depending upon the gravity of his crime, to shouts of ‘Randolph, Randolph, take an order!’”

Like other pilots in the squadron, Dixon had a “tailor-made U.S. uniform from Burberry’s…[but] used an off-the-rack British tunic with tie and shirt for work.”

For the first couple of weeks of its existence at Petite Synthe, the 17th familiarized itself with its sector and aircraft. “The air was always full of the roar of engines on a fair day, and even on days when mists hung about the plains or clouds rolled up from the south and west, there was a roar at least from the test bench,” remembered Clapp. “We watched the big bombing formations of the 211th take off in front of the hangars—twelve, fourteen, even sixteen D.H.9s getting away, one after the other, and disappearing into the haze toward Calais to get their height.”

Lieutenant Rodney Williams shot down a Fokker D.VII on July 20, 1918, to claim 17th Squadron’s first kill.

The 17th Aero Squadron crossed the lines for its first offensive patrol on July 15. Five days later it claimed its inaugural victory when Lt. Rodney Williams shot down a Fokker D.VII just east of Ostend. Later that day a congratulatory message was received from General Salmond, commanding the RAF in the field. “It was a great day with us and the enlisted men were quite as excited as the officers,” wrote Clapp. “It meant much that at last, after so many discouragements and changes, we had achieved the beginning of our offensive career.”

A party was held in the mess on the evening of July 20, an occasion tempered somewhat by the news that Lt. George Glenn from Virginia had become the squadron’s first fatality after being shot down by a Fokker.

Lloyd Hamilton had missed the party in Williams’s honor. He’d been sent on leave to London a few days earlier, but by the start of August he was back, a day after Robert Todd recorded the squadron’s second victory.

On August 7, the day before the British Fourth Army launched their big offensive in Amiens, Hamilton and Merton Campbell were on an offensive patrol over Armentières. The pair were flying at 16,000 feet when they spotted a patrol of eight German Fokkers 8,000 feet lower. Refreshed after two weeks in London, Hamilton dove on his enemy with relish. “I settled on the tail of one Fokker and fired 200 rounds into him as he spiraled down,” he wrote in his combat report. “I followed him down to 5,000 feet at which point a cloud of black smoke issued from his cockpit and he went down in an extremely steep spiral through a cloud, apparently completely out of control.” Hamilton emerged from the cloud straight into the path of a second Fokker. The German fired; Hamilton climbed, turned, and came out behind his prey. He sent a stream of bullets into the aircraft. “As he dove away, Lieut. Campbell came in on one side and then on to his tail, firing several bursts,” wrote Hamilton. “I saw E.A. crash into a green field just east of Armentières. Lieut Campbell was at about 1,000 feet and I was at 500, both getting badly machine-gunned. When I was going toward the lines I saw another Fokker biplane badly crashed on the ground just east of Armentières in a trench.”

Robert Todd claimed the squadron’s second German a few days later.

When the British ground offensive at Amiens began, the 17th Aero Squadron was ordered to escort 211 RAF Squadron on a series of raids on the docks at Bruges. It was dangerous work requiring the aircraft “to fly out to sea and attack from east of the target, this making it a very long trip over the lines.”35 On one raid two Fokkers appeared out of the sun and Ralph Gracie was falling earthwards in flames before he’d barely had time to react. Two more pilots were wounded, including Ralph Snoke, another of the eight original members of 17th Aero Squadron.

Colonel Jack Cunningham, C.O. of the 65th Wing, wanted a “show,” something spectacular with which to delight the RAF top brass. Studying the map of the Flanders sector, he pointed to a large German airfield at Varsenare, a few miles to the west of Bruges. It was home to at least five squadrons of Gothas and Fokkers, all of whom were responsible for considerable inconvenience in recent days, and Cunningham had received word that the château on the northeast corner of the field was the pilots’ quarters. He wanted it bombed.

There was a problem, however: the target lay thirty miles behind German lines. Scrupulous planning would therefore be required by the four fighter squadrons chosen to support 211 Squadron for the raid: 17th and 148th, and 210 and 213 Squadrons RAF. Cunningham organized a series of dummy raids in the Calais area, “with the approach and departure in predetermined formations to avoid collisions.” He even took to the air in a Camel, accompanied by Sam Eckert and Harold Fowler, to supervise the dress rehearsals.

On August 11, two days before the raid, 148th Aero Squadron was moved out of the 65th Wing, and transferred south to reinforce the RAF in the Amiens sector. Their sister squadron, 17th Aero, saw them off in fine style, hosting an extravagant dinner in the mess on the night of August 12, what Clapp later described as a “great evening.”

Colonel Jack Cunningham, commanding officer of the 65th Wing, was an aggressive leader.

August 13 dawned misty as Hamilton and Goodnow led their men toward the machines being run up by their ground crew. Among the twelve pilots chosen for the mission were Frank Dixon, Merton Campbell, Robert Todd, and William Shearman. Initially everything went according to plan. The four squadrons rendezvoused over the sea, each machine carrying four Cooper bombs, with the exception of flight commanders who had phosphorous bombs to drop near the machine gun emplacements guarding the aerodrome.

The flock of aircraft flew up the coast at 2,500 feet, clouds whipping across the aircraft and scattering the formation. Lieutenant Colonel Cunningham became separated from the rest of the raiders, as did Dixon.

Looking down from his cockpit, Hamilton recognized the port of Zeebrugge up ahead. He banked to the right and went into a shallow dive, with the other ten Camels of 17th Aero squadron following in perfect formation as the target came into view. An RAF communique described what happened:

After the first two Squadrons had dropped their bombs from a low height, machines of No. 17th American Squadron dived to within 200 feet of the ground and released their bombs, then proceeded to shoot at hangars and huts on the aerodrome, and a chateau on the N.E. corner of the aerodrome was also attacked with machine gun fire. The following damage was observed to be caused by this combined operation: a dump of petrol and oil was set on fire, which appeared to set fire to an ammunition dump; six Fokker biplanes were set on fire on the ground, and two destroyed by direct hits from bombs; one large Gotha hangar was set on fire and another half demolished; a living hut was set on fire and several hangars were seen to be smoldering as the result of phosphorus bombs having fallen on them. In spite of most of the machines taking part being hit at one time or another, all returned safely, favorable ground targets being attacked on the way home.

Colonel Cunningham had been the first to return to Petite Synthe, followed a short while later by Dixon, who having lost contact with the squadron, went off on a lone bombing mission to Ostend. The pair stood by their machines, surrounded by ground crews, peering at the oyster gray sky to their east. “One by one the pilots came back, their machines badly shot up, but they themselves safe and sound,” remembered Clapp. Each of the American pilots was accorded a hero’s return as he leapt down from his machine. Questions came thick and fast and the answers in excited, breathless tones. Hamilton described how he’d “dropped four bombs on north hangars from 200 feet, shot fifty rounds into the windows of the château, made four circuits of the field shooting at a row of five Fokkers on the ground with engines running.” Todd explained that his four bombs had landed on the château, from no more than 250 feet. Did he see any other damage? “Saw seven enemy machines burning on the ground.”

Lieutenant Albert Schneider had seen a pilot climb into the cockpit of his Fokker. He admired his courage, but he still opened fire and shot the man dead. Shearman couldn’t say the damage caused by his bombs but he’d killed one man running toward a machine gun emplacement, fired a long burst into four Fokkers on the ground, and “on my way home [fired] at the crew of the anti-aircraft gun to the west of the aerodrome.”36

Cunningham had done it; he had pulled off a “show” that soon brought a warm message of congratulation from the Chief of the American Air Service. Addressed to Maj. Harold Fowler, the letter ran:

This office is in receipt of your letter of August 16th enclosing the details of the work of the 17th Aero Squadron on August 13th in its attack of the German airdrome at Varssenaere [sic]. Chief of Air Service is particularly pleased with the splendid work done by this squadron on the date mentioned. It shows the aggressiveness and working together as a squadron, which we are endeavoring to obtain for all units of the American Air Service.

I have furnished a copy of your report to the Intelligence Section, General Staff, who have informed me that they were greatly pleased with the work done and have cabled the information back to the United States for publication.

Please express to the Squadron Commander, pilots and soldiers of the Squadron the appreciation of the Chief Air Service for the excellent work performed by them.

[Signed] R. O. Van Horn, Colonel, A.S., Assistant, C.A.S.

Lloyd Hamilton was awarded the British Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for his “dash and skill” during the raid on Varsenare. Other members of 17th Aero squadron involved in the attack were less fortunate. Within twenty-four hours, two were dead. William Shearman was shot down and killed on an offensive patrol, and, a couple of hours later, Lyman Case’s tail was sliced off by an enemy aircraft out of control at 14,000 feet. The German pilot had been shot dead by Glenn Wicks, a horrified witness as his friend’s machine “went straight down flopping about.”

Wicks was killed later in the summer, as was Merton Campbell, shot down on August 23. Five days before the death of Campbell, 17th Aero Squadron had moved south to Auxi-le-Château, where the previous month the top British ace, James McCudden, had been killed in a flying accident. Death seemed to claim them all in the end, even the very best.

Hamilton was some way short of McCudden’s fifty-seven victories when he arrived at Auxi-le-Château, but he was proving to be one of the top American aces that summer. On August 20, Hamilton wrote his parents in Vermont that he hoped his new base would prove a “happy hunting ground.” It did. The following day he took his tally to nine, shooting down a Fokker and then an observation balloon. August 21 also marked the opening day of the Battle of Bapaume, an offensive launched by the British Third Army, and the second phase of the Battle of Amiens.

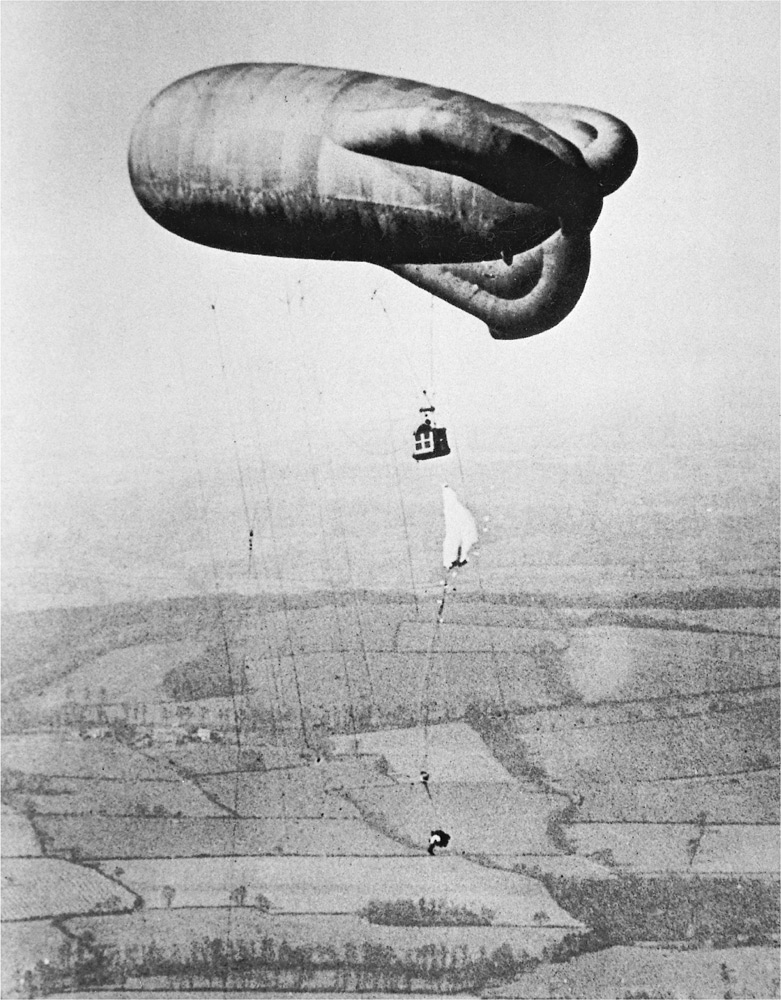

Unlike British pilots, balloon observers were issued parachutes; this one has just been deployed.

Campbell was killed in a low-level bombing sortie, and by August 24, the strain was beginning to tell on the squadron. Wicks described it in a letter home as “strenuous and nervous work to say the least.” Even Hamilton felt a sense of foreboding, telling the squadron’s medical officer, Lt. Jacob Ross, an old friend from the University of Syracuse, that “if this push continues, you will be writing home to my parents.”

Shortly after midday on Saturday August 24, Hamilton took off, accompanied by Lt. Jesse Campbell. The pair turned northeast toward the German lines. This was to be a day of improvisation, attacking targets as and when they arose. At 2:10 p.m. they bombed an enemy building close to the Bapaume to Cambrai road, and then they headed north to an observation balloon they could see. “We attacked an enemy balloon at about 1,000 feet,” wrote Campbell in his report. “I fired 150 rounds at close range and [the] balloon burst into flames and went down. I saw Lieut. Hamilton firing all the way down at close range on it.”

Suddenly Hamilton’s Camel shuddered, and then went into a spin. Campbell was forced to climb away from the scene because of intense ground fire. Back at Auxi-le-Château, he told Dr. Ross that Hamilton had been hit but he hadn’t seen his fate thereafter. That evening Ross wrote to Hamilton’s parents. He recounted Campbell’s description of the incident but was straight with them. There was a good chance their son was dead, he wrote, but they should cling to “the small hope that ‘Ham’ might still be alive and a prisoner.”

As Ross wrote Hamilton’s parents, the missing pilot’s best friend, William Tipton, sat slumped in the mess, alone with his grief. The whole of the next day, recalled Frederick Clapp, Tipton “played the gramophone to himself, holding his big, slightly bald, blond head in his hands, a dead cigar in the corner of his mouth. He did nothing but stare into the gramophone, while it wheezed and growled and squeaked out ‘Old Bill Bailey,’ ‘The Mississippi Volunteers,’ or ‘Poor Butterfly.’”

William Tipton of 17th Squadron survived being shot down to spend the rest of the war a prisoner.

On August 26, the 17th Squadron was instructed to assist the 148th Aero Squadron providing escorts to low-level bombing missions. Tipton led off eleven Camels, climbing slowly into a howling gale with winds up to 70 miles per hour. “Crossing the lines there were several Fokkers which attacked us, with several other flights of Fokkers coming through the clouds on us,” recalled Frank Dixon. “I was not very high. In the general mêlée one Fokker appeared in front of me. I fired, he went over in his back and down.”

Dixon spotted another Fokker closing in on a Camel. He intercepted the enemy aircraft and sent it into the ground with a short twenty-round burst. “Then my only thought was to get home,” he admitted. “Believe me, at such a low altitude, with pom-poms following me at every quick maneuver, it was no cinch. I managed to arrive back at the squadron.…Tipton, Todd, Frost, Jackson, Bittinger, and Roberts did not.”

In time, word was received that Howard Bittinger, Lawrence Roberts, and Harry Jackson—the latter on his first offensive mission—were dead. A month later, a postcard arrived at the squadron through the Aviation Officer in London. It was from Tipton. He, Todd, and Frost were all prisoners of war.