Claude Grahame-White was not only a pioneer pilot; he was also an aviation visionary. Library of Congress

A Useless Fad

On the penultimate day of December 1911, two young men greeted each other warmly in the dining room of New York’s Plaza Hotel. They were debonair, assured, their words and mannerisms those of men who had made their mark in the world. With them was a reporter from the World newspaper.

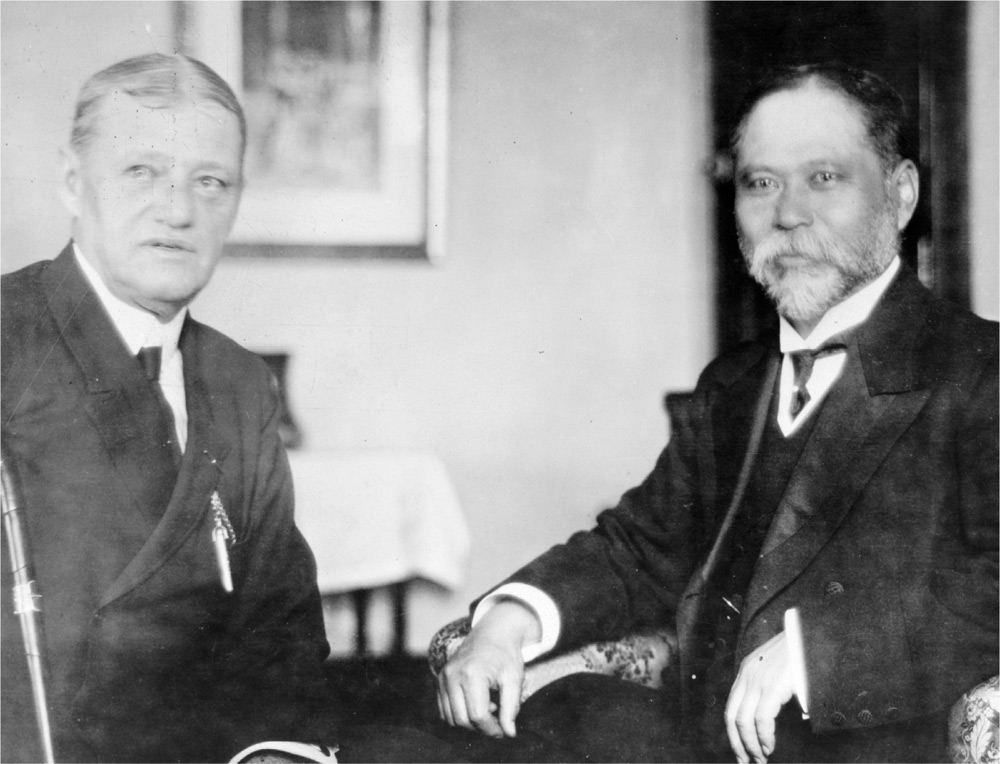

One of the men, Walter Brookins, was American, a native of Ohio and the first pilot to be trained by the Wright brothers. The previous year he had soared to an unprecedented height of 4,380 feet. His dining companion was Claude Grahame-White, a dashing Englishman with a touch of the dandy about him. He was a celebrity as much as an aviator and, in 1910, had taken the United States by storm winning the International Aviation Cup at New York’s Belmont Park and also scooping a $10,000 first prize in a race from the park to the Statue of Liberty and back.

Grahame-White was back in Manhattan visiting friends and the World wanted to hear both his and Brookins’s views on the future of aviation. The conservative American was of the opinion that this new mode of transport still had a long way to go; his eyes nearly popped out of their head when the radical Englishman in turn declared over his first course that he would “make a bet with anyone that in twenty years’ time we will be flying across the Atlantic Ocean in fifteen hours.”

The discussion turned to military aviation, and again Brookins erred on the side of caution. The German Zeppelin dirigible was, he said ominously, a most “dreadful weapon” that could revolutionize warfare. Grahame-White snorted dismissively. Why, the dirigible was obsolescent! No, the future was the airplane, said Grahame-White, adding as he reached for his glass, “I have made it a rule of late to avoid speaking about the uses of the airplane to avoid being laughed at.” The reporter asked why people laughed at him. “People don’t realize the importance of this branch of the military service,” replied the Englishman. “It is enough to say that the airplane’s field in military and naval work is unlimited.”

Claude Grahame-White was not only a pioneer pilot; he was also an aviation visionary. Library of Congress

Some of those who laughed at Grahame-White were military men. Britain’s chief of the Imperial general staff in 1910, William Nicholson, derided the airplane as “a useless and expensive fad,” a view shared by Rear Adm. Robley D. Evans, erstwhile commander of the “Great White Fleet,” the popular name bestowed upon the U.S. Navy battle fleet that circumnavigated the globe from 1907 to 1909 on the orders of President Theodore Roosevelt. Evans was widely quoted in newspapers in September 1910, declaring that “flying machines have plenty of work ahead of them before navy men will consider them a serious menace.” Evans was speaking shortly after Congress had refused to fund research into the use of the airplane as a weapon of war. Evans agreed with his political masters, rubbishing suggestions an airplane could ever sink a battleship. “It is only necessary to state that our service revolvers are deadly weapons at a range of 300 feet and that several hundred experts on each ship would be using them in earnest.”

Rear Admiral Robley D. Evans (left) of the U.S. Navy was skeptical that aircraft would ever pose a threat to battleships. Library of Congress

Evans commanded the “Great White Fleet,” the popular name bestowed upon the U.S. Navy battle fleet that circumnavigated the globe from 1907 to 1909. Library of Congress

Writing in the September 1910 issue of Popular Mechanics, Capt. Richmond P. Hobson, a naval man who had resigned his commission in 1907 to become Democratic representative from Alabama, said “the offensive power of the airplane…is almost negligible.” This view was challenged in the December issue of the journal by noted engineer Victor Lougheed, whose younger brothers, Allan and Malcom, would later form the Lockheed Aircraft Company. Far from the airplane having a negligible impact in war, Lougheed believed it was the battleship that was obsolescent, writing: “They must surely take their final place with the other extravagances and follies of progressing mankind with such other colossal extravagances of human efforts as the pyramids—like them wonders of a world, but regarded as such more because of their uselessness and worthlessness than of such downright efficiency and effectiveness as pertains to the irresistible advance of the inexpensive, developing and wonderfully promising vehicles of the sky.”

Lougheed finished his essay with a grave warning for the U.S. government and military: “To assume that the ‘offensive power of the airplane…is almost negligible’ is to court an obsession with the present status that will defeat even a most moderate insight into the future. All the probabilities are that the offensive power of the airplane of the future, and even of the present, is as much underrated as the defensive and offensive power of the battleship against aerial craft is overrated.”

Nonetheless, the faith of the U.S. military in the airplane eroded still further in 1913 during the Mexican War. The ten Curtiss biplanes sent to the region didn’t perform well and “proved more of a liability than a help, breaking down, having forced landings and diverting soldiers and cavalry on the ground from their traditional tasks to aid the stranded pilots.”1

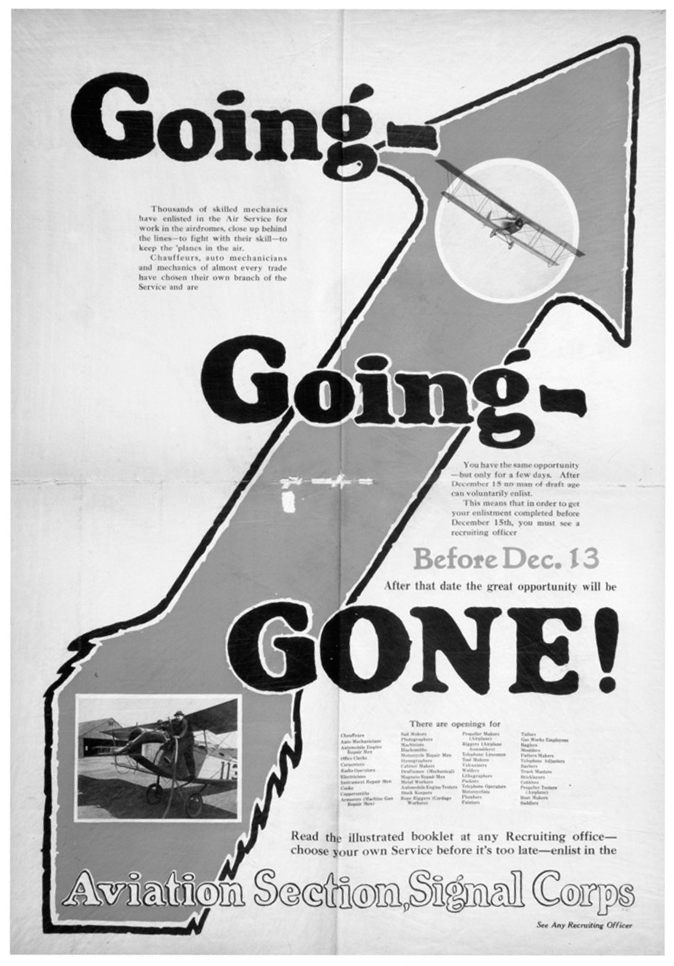

Sensing a major conflagration was about to erupt in Europe, Congress felt obligated in July 1914 to pass an Act to create the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps, but it was a desultory measure, and the unit’s strength was set at sixty officers and 260 enlisted men. To train this ancillary of a subordinate branch, the government grudgingly permitted only the smallest of grants, and when war broke out in Europe on August 3, 1914, the Aviation Section had just five aircraft.

Fortunately for the British, at least, their military wasn’t staffed entirely by men whose views were firmly entrenched in the past. Among those with foresight were Douglas Haig, chief of the general staff in India, and Lord Horatio Kitchener, appointed secretary of state for war in summer 1914.

One of Kitchener’s first acts was to order the nascent Royal Flying Corps (RFC), formed in 1912, to raise five more squadrons. Hugh Trenchard, officer commanding the military wing of the Royal Flying Corps—the man tasked with overseeing the expansion—was delighted, but he was also daunted. Creating five squadrons was a monumental challenge in a country where those who had even clapped eyes on an airplane were in the minority.

In late August 1914, Maj. Gen. Sir Sam Hughes, Canadian minister of militia and defense, suggested to Trenchard that North America might offer a fertile recruiting ground. After all, the United States was the birthplace of the airplane and there were many hundreds of aviation enthusiasts.

Lord Kitchener was open to the recruitment of pilots to the RFC from Canada but rejected the idea of enlisting Americans. But neither he, nor anyone in the British military, envisaged the extent of the carnage in the world’s first truly technological conflict. Between July and December 1916, the RFC lost 499 of its aircrew, with a further 250 incapacitated through physical or psychological wounds. Machines could be replaced—and by late 1916 “a rapidly expanding labor force had already reached 60,000 engaged in the manufacture of airplanes and another 20,000 in building aircraft engines”2—but finding the men to fly them was more of a challenge. Throughout 1916, scores of young men, many fresh out of school, were posted to combat squadrons in France undertrained and ill-equipped to take on the German air force. Most were shot out of the sky within days.

An early recruitment poster encouraging young Americans to enlist in the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. Library of Congress

In August 1916, as losses began to mount, the RFC began actively recruiting in Canada, placing advertisements in newspapers calling on men to “Enlist as an Air Pilot.” All tuition was free, the ads trumpeted, and from the date of enlistment, trainee aviators would receive $1.10 per day with 25¢ per day flying allowance. Provided prospective enlistees were between eighteen and twenty-five and possessed of a “good moral character with such an education and upbringing as would fit them for positions as officers,” they could be granted a commission at the end of a three-month course.

Early in 1917 the British finally turned to the United States. Lieutenant Colonel C. G. Hoare, the commanding officer of the RFC in Canada, persuaded the American military to allow him to visit cities including Chicago, Boston, St. Louis, and Minneapolis in search of manpower, while the British also opened a permanent recruiting mission at 280 Broadway, New York City. Within a short space of time Hoare had drafted in four more officers to deal with the demand. On June 9, 1917, the New York Times reported that the previous day, one hundred young men of “sound physique” and “considerable experience with machinery” had been accepted into the RFC. The paper described the recruits as “British and Canadian subjects,” which was hogwash, as the journalists well knew. The vast majority were young Americans “tired of waiting for their own country to take her place with the Allies.”3 They were willing to trade nationalities for a time if it meant the chance of seeing some adventure.

Americans had been made aware of the exploits of the RFC thanks to the efforts of anti-isolationist newspapers. In June 1916 the Connersville Evening News told its readers in Indiana of Britain’s “Birdmen Heroes,” glamorizing the RFC with tales of “unbelievable” skill and pluck in the skies over France. The following month the New York Tribune syndicated a feature to numerous regional papers that was pure propaganda for the British military. “Looping the Loop Over London” was the heading of the full-page article, which was accompanied by three photographs of England’s newest warplane and a breathless account of a trip over London by the Tribune’s Jane Anderson.4

Describing the thrill of “looping the loop” over London’s Hyde Park at seven thousand feet, an enraptured Anderson told her audience: “We circled toward the aerodrome. We dropped down, spiraling…the final evidence of the superb construction of his majesty’s biplane, designed for the destruction of enemy aircraft. I had full opportunity of discovering whatever weakness or fallibility might have been in her. There was none.”

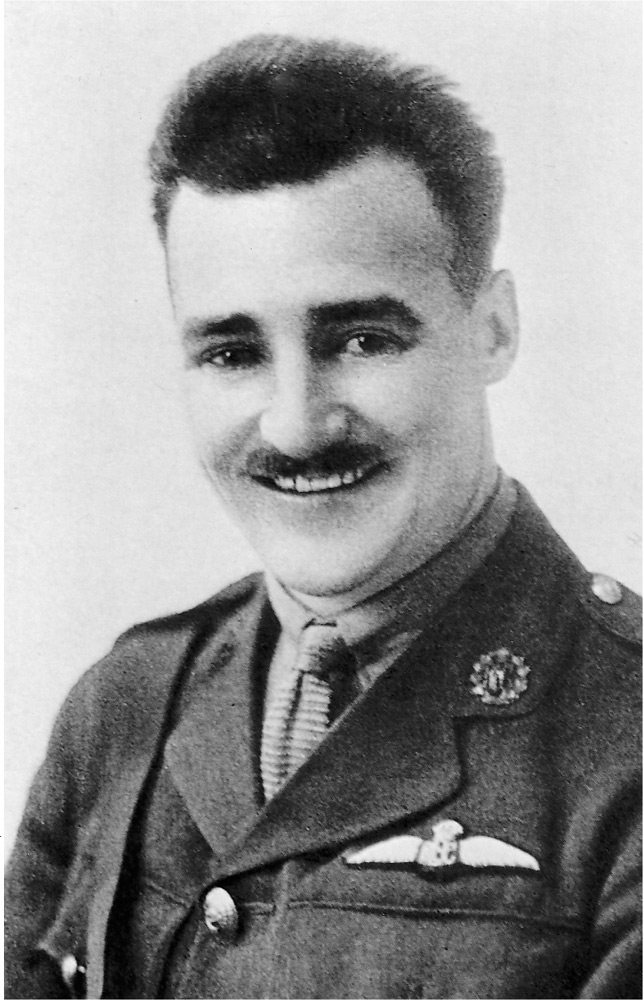

Illinois native Pat O’Brien initially joined the Aviation Section of the U.S. Signal Corps but, frustrated by the lack of action, he crossed to Canada and joined the RFC. After being shot down, O’Brien escaped and wrote a best-selling book about his experiences.

The British were delighted at Anderson’s puffery. What propaganda! What better way to sell the RFC to Americans than a stirring account of their very latest warplane? And so it proved, as dozens of restless young Americans, unable to resist the temptation of taking to the skies in combat, crossed the border into Canada and offered their services to the RFC. The volunteers received a medical examination and, once given a clean bill of health, were sent east to Camp Borden, Toronto.

Borden was surrounded by lakes—Huron to the north, Ontario to the south, and Simcoe to the east—but the thousand acres given the RFC by Canada’s Department of Militia and Defense were ideal for the business of flying.

Construction on transforming the area into an air base began in January 1917 with 1,700 laborers working furiously to level out the sandy soil, sew it with grass seed, and install “an excellent road system, a first rate water supply and electrical system…together with special telephone communications to Toronto and neighboring towns.” In time there would also emerge from the prairie a one-hundred-by-forty-foot swimming pool, tennis courts, and nine hole golf course, making it “the finest flying camp in North America.”5

Working by arc lamps throughout the night, often in temperatures as low as twenty-five degrees below zero, the laborers finished Borden so quickly that training could begin by April 1917. Three months later, the Boston Globe reported that Lt. Allan Thomas, a British combat veteran, had opened a recruiting office in the city and was inviting young men to present themselves for an interview and medical examination between the hours of 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. “He hopes to send at least 200 within the next few weeks to Camp Borden near Toronto,” explained the Globe. “At Camp Borden there are 120 airplanes for men to learn to fly with and almost daily as many as 50 machines are in the air at the same time.” Thomas was confident that the city of Boston would provide the RFC with more cadets than New York. On the day the correspondent from the Globe visited the recruiting office, four Americans passed muster and were dispatched to Canada, each dreaming of earning that most treasured of aviation titles—“ace.”