We have abolished pyramidal architecture to arrive at spiral architecture. A body in movement, therefore, is not simply an immobile body subsequently set in motion, but a truly mobile object.

• UMBERTO BOCCIONI, “PLASTIC DYNAMISM”

[The vortex is] the most highly energized statement that has not yet SPENT itself it [sic] expression, but which is the most capable of expressing.

• EZRA POUND, “VORTEX”

THE LIFE OF CURVES

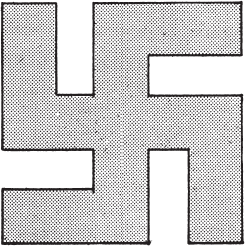

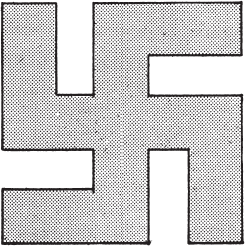

Perhaps no other scholar of spirals has ever evinced more enthusiasm for his topic than has Theodore Andrea Cook. In 1914, Cook, a London art critic and well-known former editor of The Field, an illustrated magazine appealing to gentlemen sportsmen, completed more than a dozen years of research into spiral forms of all kinds.1 In his sprawling (and sprawlingly subtitled) book The Curves of Life: Being an Account of Spiral Formations and Their Application to Growth in Nature, to Science, and to Art; With Special Reference to the Manuscripts of Leonardo da Vinci, Cook offers a detailed description of insect and conch shells, plant life, animal horns, various parts of the human body (thigh bone, umbilical cord, ear canal, hair), and spiral nebulae, often drawing on mathematical formulas to demonstrate what he views as the perfect proportion of his specimens. Cook, whose decided preference is for the miraculous logarithmic spiral (which he calls the “curve of life” and “essence of beauty”), then goes on to analyze examples from Renaissance and Baroque architecture, sculpture, and painting and, in addition to exploring spiral staircases, columns, and volutes, shows how both Leonardo’s pursuit of aesthetic perfection and Albrecht Dürer’s vaunted advances in the idea of perspective rely on spiral and helical formations. According to Cook’s preface, dated March 28, 1914, “Spirality (if the word may be allowed) is a generalization of far-reaching importance,” and to make the case for this generalized importance, The Curves of Life is “profusely illustrated” with 415 illustrations and 11 plates. One of these illustrations happens to be “The Lucky Swastika,” which, according to Cook, is “one of the most ancient and widespread of all symbols,”2 connected both to the orientation of the sun and to the growth of the lotus flower, the latter itself, according to Cook, considered a “sacred” spiral form (figure 8).

Within a few short months of the publication of The Curves of Life, much of Europe would be at war—the Great War, of course, which preceded the world war emblematized by the swastika—by the end of which few devotees of the arts would unequivocally espouse universal, triumphant notions of beauty such as Cook’s (whose next publication, not incidentally, concerned the Olympic Games). But these vitalist, unabashedly aesthetic notions had, of course, already been exposed to examination and attack for some time. Indeed, just as Cook’s ideas were coalescing, vanguardist European artists of diverse and even antagonistic allegiances had begun to draw on the figure of the spiral not to express “the profound significance … of mankind” as eternal beauty, but precisely as absurdity and hideousness.3

This chapter traces the spiral’s crucial role in articulating the foundations of Italian Futurism and the London-based literary and visual-art movement known as Vorticism. Its focus is on the way spirals shed their organicist, residually Euclidian, nineteenth-century associations of “life” and “growth” (Goethe and Hegel), and began to express a new kind of creative potentiality—one that explicitly embraces a destructiveness that is itself contrarily viewed as life-affirming. The chapter begins by briefly encountering Alfred Jarry’s terroristic theater and narrative: specifically the play Ubu Roi and the novel The Exploits and Opinions of Doctor Faustroll, Pataphysician, both of which prominently feature spirals of this new, destructive type, and both of which were acknowledged by Italian Futurists as important precursors. My focus then turns to some of the key writings and visual art of Futurism, in which spirals occupy a powerful position in articulating both speed and potentiality—ideas that for the Futurists are by no means to be confined to the aesthetic sphere but are by their very nature imbricated in the political sphere. The last part of the chapter explores how some of the prime movers of Vorticism—Wyndham Lewis, Ezra Pound, and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska—explain the vortices of Vorticism, itself ostensibly set firmly against the perceived effeminacy of Italian Futurism, and how spirals play a role in articulating some of the masculinist and racist presumptions of the movement. Throughout the chapter, we will be attentive to the ways the spiral image negotiates ideas of the vanguard, (anti-)aesthetics, and early-twentieth-century conceptions of history and the geopolitical.

UBU AND THE “UNFORESEEN BEAST”

In Alfred Jarry’s raucous play Ubu Roi (1896), the title character is depicted as a nonchalantly rapacious monster insatiably seeking food, land, money, and blood, destroying and absorbing everything and everyone he encounters. This cyclonic, destructive absorption is emphasized by Jarry’s own irreverent treatment of precursors, including Rabelais and, especially, Shakespeare, whose Macbeth is obviously a model for Ubu’s bloody power grab. When Jarry designed a woodcut of his “grotesque anti-bourgeois” hero, he depicted Père Ubu as a rotund, hooded dummy with an oddly blank, feline facial expression; thin arms under which he is pinning a kind of stick (that could be his oft-mentioned “green candle”); stubby little legs; and, most noticeably, a large Archimedean spiral splayed across his torso, emanating from, or perhaps ending at, his navel (figure 9). Although the rationale for portraying Ubu in this manner is never directly explained in the play—and has not been pursued by scholars—a glance at Jarry’s offhand articulations of “’pataphysics” provides an important clue.

In the book 2 of his “neo-scientific novel” The Exploits and Opinions of Doctor Faustroll, Pataphysician, written in 1898 but not published until 1911, four years after Jarry’s death at age thirty-four, the author of Ubu declares ’pataphysique to be “the science of that which is super-added to [se surajoute à] metaphysics, whether within or beyond the limits of metaphysics.”4 If metaphysics ostensibly studies that which is beyond the physical, ’pataphysics (whose little recoiling spiral apostrophe, Jarry claims, is used “to avoid a simple pun”)5 extends “as far beyond metaphysics as the latter extends beyond physics.”6 Yet despite this ostensibly long reach, ’pataphysics is turned not toward the universal, but toward the particular and, especially, the “accidental.” Accordingly, it “examine[s] … the laws that govern exceptions [les lois qui régissent les exceptions],”7 as will, eventually, the rather less facetious approaches to the question of exception taken by Carl Schmitt and Walter Benjamin.8

As if to set out such an “examination,” Jarry launches into a raunchy story of his Circassian-born hero, Faustroll, whose name seems to be an amalgamation of Goethe’s soul-selling Faust and the deflating “troll.”9 Chapter 33 of Faustroll’s saga is called “Concernant les termes” (Concerning the Termes)—termes in French referring not only to “terms” in a legal, contractual sense but to termites or “woodworms,” spiral-shaped and destructive. Here, Faustroll has met a woman curiously named Visité (Visited), a “bishop’s daughter” (!) who has a bed made out of elaborately hand-carved wood. On the wall over this bed, itself obviously a parody of Penelope’s Odysseus-carved bed in Homer’s Odyssey, is found a “spiral-painted tapestry,” under which Visité “desired to discover” whether Faustroll had a heart “capable of pumping out with its open and closed fist the projection of circling blood.”10 The potent and destructive eroticism of this set of spirals is made even clearer when, after at least two hours of what one hesitates to call “lovemaking,” Visité is unable to “survive the frequency of Priapus.”11 This multiply spiral motif (woodworms, tapestry, circulating blood, trajectory of seminal fluid) is then immediately extended in the following brief chapter, “Clinamen,” which, as we have noted, is what Lucretius called the unpredictable swerve of atoms. In Jarry’s text, one finds an astonishing description of a “Painting Machine” amid a “Palace of Machines” that is “the only monument left standing” in a deserted and razed Paris of the not-so-distant future. The machine, itself named Clinamen, dashed itself “like a spinning top” against the pillars and “followed its own whim blowing onto the walls’ canvas a succession of primary colors,”12 rather like a mobile automatic painting of the type that Damien Hirst employed a century later.

Faustroll’s little parable concludes, charmingly, “the unforeseen beast Clinamen ejaculated onto the walls of its universe.”13 In Jarry’s text, written (to paraphrase Jarry himself) in “the year –2” of the twentieth century, spiral forms are thus associated with sexuality and power, sexuality-as-power. This power would allow “’pataphysical” contemporary art-of-the-future to “dash itself” against the architecture of the decaying old and, unforeseen, “ejaculate against the walls” with its destructively primal, primary, priapic/pudendic colors. In this explosively violent vision, body limns machine: indeed, body is a kind of sex- and art-making machine.

It is far from incidental that the parable of Clinamen unfolds in a burned- or bombed-out Paris. Jarry’s aim, like that a generation of ’pataphysicians and ’pataphysical fellow travelers after him (including, as we shall see, Marcel Duchamp) was not merely to mock the presumptions of aestheticians and belle-lettrists, but to buzz energetically in the field of the political rather like Clinamen’s spinning top. This aim is apparent when one returns to Jarry’s play, which is subtitled ou, les Polonais. The action of Ubu Roi is said to take place in Poland, “c’est-à-dire, nulle part” (that is to say, nowhere): by the time of the writing and performance of the play, the nation had effectively been wiped off the geopolitical map after a century-long series of partitions by its more powerful imperial neighbors Prussia, Austria, and Russia. Of course, this notion of national extinction is rendered hyperbolically and absurdly in the play. Yet in giving incidental characters the names Jan Sobieski and Stanislas Leczinski, kings of Poland right before partition began, Jarry suggests that the Polish setting is far from insignificant; indeed, the trajectory of Ubu’s long, obscene, windy (in both senses) voyage is precisely from Poland to France—thus reversing the Napoleonic invasion of the early nineteenth century that Poles mistakenly believed would free them from fealty to their stronger neighbors, especially Russia.14 Accordingly, it could be suggested that spiral-fronted Ubu, like Clinamen, spins like a battling top from Poland “back” to France in anticipation of the destruction to come. And if one thinks ahead for a moment to the midcentury period emblematized by the not-so-“Lucky Swastika,” it is precisely Poland’s status as “nulle part,” or zone of exception beyond the pale, that allowed it to be the primary extermination arena of the Second World War.

ACCIDENTAL TOURISTS: ITALIAN FUTURISTS AND THE SPEEDING SPIRAL

Jarry’s ’pataphysics, thriving on the accidental, thus offers both spirally armored Ubu and spinning, ejaculating Clinamen as exceptionally exemplary models for destructive production. The Italian Futurists responded, in part to Jarry’s provocation, with a call to “wreck the cities pitilessly,” to torch libraries and museums, and to embrace the hard sleekness of the machine.15 First published in 1909 in Italy and France, and swiftly translated into numerous other languages (including Russian and Japanese),16 Filippo Tomasso Marinetti’s “Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism” begins with a prefatory, indeed foundational, description of an erotic-cum-anti-aesthetic absurdist reverie, one punctuated with spiral images. Marinetti describes an exhorting exclamation he makes to unnamed insomniac “friends”: “Let us break out of the hideous shell of Wisdom and hurl ourselves like pride-spiced fruit into the wide, contorted mouth of the wind! Let’s give ourselves completely to the Unknown, not in desperation but only to replenish the deep reservoirs of the Absurd!”17 Just as in Jarry, where the “unforeseen beast Clinamen ejaculated onto the walls of its universe,” here, the erotic nature of Marinetti’s justly famous exhortation is evident: breaking out of a “hideous shell”—gangue can also be translated as “matrix”—“we” should “enter” (entrons) the wide and contorted mouth (the adjective torse also invoking the noun form for “torso”) of the wind. The prosthetic vehicle through which this eroticized entry will take place is the racing automobile, which is later described, with phallic verve, as having “a hood that glistens with large pipes resembling a serpent with explosive breath [orné de gros tuyaux tels des serpents à l’haleine explosive].”18 The coiled destructiveness crucial to the Italian Futurists’ hyper-masculinized rhetoric is emblematized by this muscle-car’s serpentine hood, which stands in clear contradistinction to the feminized “hideous shell.”

Marinetti’s exhortation to hop in is almost immediately followed in the preface by a sudden swerve—a stylized description of the minor accident in which Marinetti claims to have steered his car into a ditch to avoid two bicyclists.19 The description begins, immediately after the torse/torso exhortation, with Marinetti’s macho out-skidding:

The words were scarcely out of my mouth when I spun my car around with the frenzy of a dog trying to bite its tail, and there, suddenly, were two disapproving cyclists coming towards me, shaking their fists, wobbling like two equally convincing but nevertheless contradictory arguments. Their stupid undulation [Italian, dilemma; French, ondoiement] was blocking my way—How boring! Auff! I stopped short—and in disgust rolled over into a ditch with my wheels in the air.20

The notion of speedily “swerving” to avoid two contradictory modes of reasoning—modes that would “disapprove” of the speeding automobilist (deux cyclistes me désapprouvèrent)—is crucial to Marinetti’s description not only of thinking, but of art practice, as it will be to the British Vorticists. Marinetti’s response to this “dilemma”—to skid out and then roll over into a ditch, wheels up—thereby implies an oxymoronically violent submission and a return to the canine metaphor of the previous sentence, in which a dog is portrayed chasing his tail.

Submission entails rebirth: describing how the accident threw him into a pit of dark industrial muck, Marinetti continues his prefatory outburst with a series of metaphors that again evoke the (possibly but not certainly feminine) sexualized body, connecting it through spirals with a specifically North African orientalism already invoked in the preface’s opening line (where the “friends” are introduced as standing “under mosque lamps” from the Marinetti family’s collection of knickknacks from Alexandria): “O maternal ditch, almost full of muddy water! Fair factory drain! I gulped down your nourishing sludge; and I remembered the blessed black breast of my Sudanese nurse!”21

The set of associations informing Marinetti’s oral-to-anal-to-oral reverie—mouth–ditch–sludge–mother–mud–wet nurse—catapults this primal scene of modernism from being one of speed to one of domesticity, and then to the colonial framework and toward the erotic, albeit erotic in a decidedly infantile sense: the Egyptian-born Marinetti’s dream of “hurling” into a breast is, post-crash, transmogrified and personalized into “la sainte mamelle noire de ma nourrice soudanaise.”

The specificity and miniaturization of Marinetti’s post-crash sucking dream does not by any means diminish the potential explosivity of spirals, which in the list of eleven manifesto “announcements” appear in the form of automobiles, planes, and trains, the last of which are portrayed (positively) as “smoke-plumed serpents” devoured by “famished railway stations [gares gloutonnés avaleuses de serpents qui fument].”22 The controlling force of the railway station links Marinetti’s loudly self-advertised “aggressive character” of art and “scorn for woman” together in a classically Freudian topos.

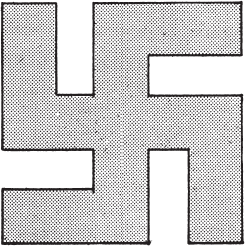

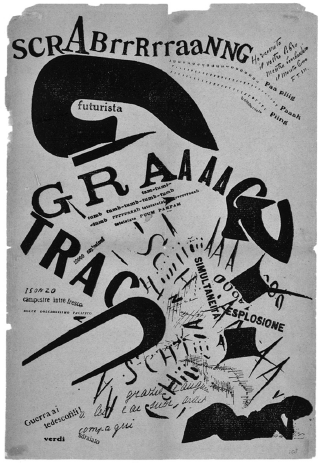

Spirals—as sign for “fire, hatred and speed,” for “spasms of action and creation,” and for the moment of exception—are found not only in the manifesto, but, frequently, in Marinetti’s drawings, including “SCRABrrRrraaNNG” (also called “In the Evening, Lying on Her Bed, She Reread the Letter from Her Artilleryman at the Front”) (figure 10), through whose multiple serpentine swerves—and especially those that surround the onomatopoetic bomb dropping (or scream of agony) “GRAAAAO”—one may easily picture the Marinettian skid-out. Indeed, this near-obsession with spiral forms spans the entirety of the Italian Futurist project, from Giacomo Balla’s Speed of a Motorcycle (1913), in which the movement of a practically invisible motorcycle is rendered as sequential spiral swirls (figure 11);23 to the same artist’s Mercury Passing Before the Sun (1914), which depicts the eclipse-like planetary transit as though it were swept up in a spiral cosmopolis (figure 12);24 and on to the later Futurist Vitorio Corona’s Dinamismo di elica e mare (1922), which connects the spiral motion of the sea to the power of machines. Yet among the Futurists, the most patient and elaborate articulation of the group’s approach to spirality is found in the writing and artwork of an early member of the Milan Futurist circle, Umberto Boccioni.

Like Marinetti, Boccioni sought to liberate Italian art from its fealty to past civilizational achievements; the past for him, as for Marinetti, is viewed as an inhibiting, constraining force. Yet, unlike the violent, spasmodic break with which Marinetti usually associated the spiral swerve, Boccioni found in spirals the form best able to express what he called “dynamic continuity.” In Pittura e scultura Futuriste: Dinamismo plastico (1914), Boccioni, using quasi-Einsteinian jargon, declares that “plastic dynamism is the simultaneous action of the motion characteristic of an object (its absolute motion), mixed with the transformation which the object undergoes in relation to its mobile and immobile environment (its relative motion).”25 Summarizing this claim of simultaneous action with the mathematical formula “environment + object,” Boccioni asserts that dynamism describes “the creation of a new form which expresses the relativity between weight and expansion, between rotation and revolution.”26 The new form, which he will go on to call “spiral architecture” (architettura spiralica) is “life itself caught in a form which life has created in its infinite succession of events.”27 This “caught” form, a form of life created by life, thus contains both a spatial (architectural) and a temporal (arrested succession) component, and the two components are as inextricable as energy, speed, and mass.

Sharply juxtaposing this project with that of the Cubists, whom he does not directly name—“this succession is not to be found in the repetition of legs, arms and faces, as many people have idiotically believed”28—Boccioni asserts the need of art to embody four dimensions: height, width, depth, and the kind of unfolding time that intersects with space: “dynamic continuity.” “We are not necessarily looking for pure form,” clarifies Boccioni, emphatically, in another jab at Cubism, “but for pure plastic rhythm, not the construction of an object, but the construction of an object’s action. We have abolished pyramidal architecture to arrive at spiral architecture. A body in movement, therefore, is not simply an immobile body subsequently set in motion, but a truly mobile object.”29 If pyramidal architecture, which must be “abolished,” implies both the static and the hierarchical, “spiral architecture,” which for Boccioni is also the foundation for painting, embodies movement and, through its rhythm, opposes the hierarchical with the fluid.

In 1913, Boccioni made several series of paintings expressing this quest for mobility, including Dynamism of a Human Body, Plastic Dynamism of Horse and Apartment Block, and a number of Spiral Constructions, including the one shown in figure 13. Here Boccioni’s painterly spiral architecture sets a purple humanoid (probably male) body, pictured headless, against what appear to be houseplants. The antipathy to Cubism is visually evident, primarily in the bright colors and softened contours in the form, which give a more organic impression than that of the clinical (and, for the Futurists, excessively Euclidian) geometry of Cubist painting. In the middle of the canvas appears a large hand/giant phallus, camouflaged by its similarity in color to what appear to be the houseplants’ pots. And yet, despite Boccioni’s theorization of bodily movement, and possible depiction of propelling phallus, the figure appears as though sitting and thus oddly static.

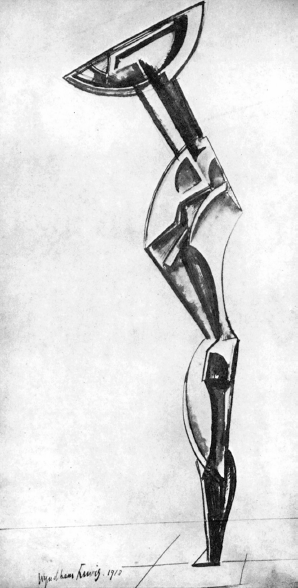

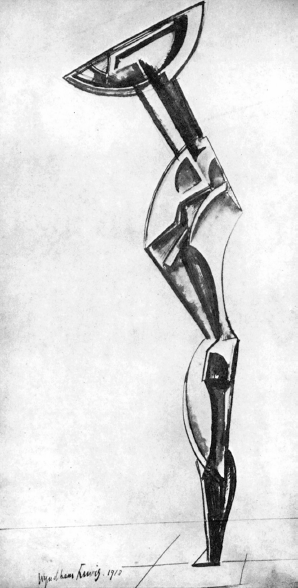

It is in Boccioni’s sculptures of this year that the principles of “dynamic continuity” are expressed most forcefully. In Spiral Expansion of Speeding Muscles and Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (figure 14), which appears to be a more finished version of Speeding Muscles, a body is depicted as if moving through space—“as if” because access to actual movement must remain imaginary and only notionally generational. Given Boccioni’s Marinettiesque extolling of newness and movement, it seems odd that his sculpture should appear at first so freighted with classical allusions (helmeted head, armored shoulders, Mercury-like winged feet) and so bulky. Yet the small, cyborg-like head; large, muscularly torsioned legs; “flaming” appearance; and square block feet manage to convey a spiralized tension between weight and expansion, between what Boccioni calls, with a clear nod to politics, “rotation and revolution.”

While Christina Poggi, laying out her thesis of the Futurists’ “artificial optimism,” identifies a potential source in Nietzsche—as did Wyndham Lewis in the Vorticist Manifesto, as we shall see30—other art historians have recognized that much of Boccioni’s vocabulary in Dinamismo plastico is actually drawn from the very different philosophy of Henri Bergson. Indeed, swaths of the Futurists’ writing on spiral architecture appear directly to quote from Bergson’s Matter and Memory and Creative Evolution, particularly their invocation of “extensity,” “vital energy” (élan vital), and the experience of time as “duration” as understood through creative intuition, as opposed to mere intellection. In L’évolution créatrice (Creative Evolution [1907]), Bergson writes, “La vie en général est la mobilité même,” and goes on to compare “the living [les vivants]” to “vortices of dust [tourbillons de poussière] carried aloft by the wind”: like these vortices, the “living turn on themselves suspended by the grand breath [or blast] of life [suspendus au grand souffle de la vie].”31 The spiral vortex, for Boccioni—and one can apprehend this in Unique Forms of Continuity in Space—tangibly represents these Bergsonian terms.

Yet by no means are these spiral effects (and affects) restricted to the philosophical, aesthetic, or quasi-scientific realms. Indeed, as art historian Mark Antliff has shown, Boccioni’s spirally mobile, striding “architecture” projects itself into space and can readily be seen as fusing with the loudly trumpeted Futurist program of national regeneration and imperialist expansion that reached its apotheosis in Mussolinism. “The Futurist correlation of the fourth dimension with a Bergsonian spatial-temporal flux made up of ‘force forms’ and ‘force lines,’ unfettered by the limitations of three-dimensional space or measured ‘clock’ time,” writes Antliff, “fused with a political program premised on intuition and an antimaterialist call for national regeneration and imperialist expansion.”32 Indeed, the very first page of Plastic Dynamism extols the “campaign to transform the consciousness of the Italian citizenry and inaugurate a political revolt against Italy’s democratic institutions,” institutions the Futurists believed to be slow, inefficient, and in thrall to bourgeois notions of individuality.33

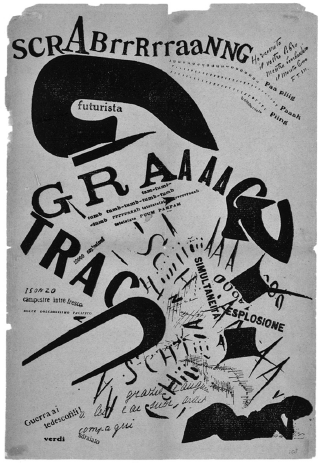

The deep connections among spirality, creativity, and territorial expansion are especially evident in Carlo Carrà’s multilingual, multimedia collage, Patriotic Celebration (also called Demonstration for Intervention in the War [1914]), in which linee-forza (an expression later associated with Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their “lines of flight”) travel in and shoot through a spiral form (figure 15). Said to have been inspired by the helical spinning of leaflets dropped from an airplane over Milan’s Piazza del Duomo, Carrà’s work, published in the Futurist magazine Lacerba, passionately sought to press Italy into a war with Austria-Hungary over disputed territory, including Trento and Trieste.34 Along with text taken from Marinetti’s Zang Tumb Tumb—in Carrà’s painting, it is called “Zang Tumb Tuuum”—and invocations of the speed of airplanes (“aviatore,” “ITALIA, battere il record,” and, especially interestingly, “eliche perforanti” [perforating propellers or helixes]), there are numerous Italian flags and as-if-vocalized declarations of “EVVIVAAA L’ESERCITO” (LO-ONG LIVE THE ARMY).35

The barrage of evidence thus clearly demonstrates that the spiral image allowed many of the most important Italian Futurists a means of expressing a belligerence intimately linked to creativity, a belligerent creativity that leads ineluctably from the very form of an object to an expression of temporality and historicity, to a willed outcome in the geopolitical realm—including Italy’s occupation and/or annexation of the former Austro-Hungarian–controlled areas of what is now eastern Italy and the former Ottoman-controlled areas of Ethiopia/Eritrea, Somalia, Libya, and parts of what are now Albania, Croatia, and Greece.

LAUGHING LIKE A BOMB: BRITISH VORTICISM AND THE EXPLOSIVE SPIRAL

The Futurists’ artistic production and, to an even greater extent, their widely broadcast swaggering pronouncements were to have almost immediate influence throughout vanguardist European literature and visual art. Futurist ideas of spiral movement and emanation gave both a name and a directionality to a would-be revolutionary literary and artistic British group, the Vorticists, who, in their organ Blast (1914–1915), railed against the perceived effeminacy and “automobilism” of the Marinetti circle but deployed many of their precursors’ central motifs and tactics.36 It is hardly surprising that a movement named Vorticism—from vortex, Latin for “whirling motion,” a term used by Descartes in his description of the origin of matter—should be concerned with spirality. But in the pages of Blast, the frequency with which spiral vortices serve as a figure for a specific kind of twisting, sucking, recoiling explosiveness is remarkable.

In “Great Preliminary Vortex,” the preface to the two “manifestos” of Vorticism, Wyndham Lewis, speaking for the collective of London-based artists, notoriously and hilariously “blasts” phenomena from “bourgeois Victorian vistas” to French “poodle temper” to the English climate (also cursing, with an “expletive of whirlwind,” British aesthetes) and then calmly and benevolently “blesses” English ships, ports, and hairdressers (for their “mercenary” war on “wildness”), ultimately asserting as the first principle of the manifesto, “Beyond action and reaction we would establish ourselves.”37 Here, with notable similarity to Marinetti’s swerving around two, or beyond two, bi-cyclic modes of thought, Vorticism will “set up” the “violent structure of adolescent clearness between two extremes.”38

In the pages of Blast, the primary means of expressing this elusive, conditionally posited adolescent “beyond” or “between”—a zone also reminiscent of the “’pata” in Jarry’s ’pataphysics—is through spiral images, both linguistic and visual. In Group, Cuthbert Hamilton depicts geometrically rigid and curved spaces with attention to, and a tension between, explosiveness and collapse. Radiation, by Edward Wadsworth, who elsewhere in the same issue of Blast favorably reviews Kandinsky’s On the Spiritual in Art (wherein the latter advocates “the abstract element” in art), conveys a frenzied sense of illumination with its multiple sources of incandescence, some machine-generated. And, although it did not appear in Blast, Vorticist fellow traveler Christopher R. W. Nevinson’s painting A Bursting Shell similarly emblematizes the Vorticist attachment to spiral incandescence, linking it to explosive destruction (figure 16).39

Lewis’s own sketch, in Blast, for a sculpture (figure 17) sharing the same title as his utterly radical play The Enemy of the Stars, looks like a slimmed-down version of the cyborg’s leg and head from Boccioni’s dynamically continuous Unique Forms of Continuity in Space. The Enemy of the Stars, whose name clearly draws on the Futurist Manifesto’s concluding “insolent challenge to the stars,” conveys a sense of drilling downward and broadcasting outward—two central motifs from Lewis’s manifesto. In his analysis of this image, art historian Hal Foster writes of two hardenings that “seem to converge: on the one hand, with a head like a receiver, the figure appears reified from without, its skin turned into a shield; on the other hand, stripped of organs and arms, it appears reified from within, its ossature turned into ‘a few abstract mechanical relations’” (the embedded quotation is from T. E. Hulme, an early translator of Bergson). “In either case,” Foster concludes, “it looks the part of an ‘enemy of the stars.’”40 Yet, bearing in mind Boccioni’s notion of dynamism, it is possible to view this sculpture less as “ossified” psychoanalytically or politically and more as an attempt to drive down, as though with a spiral screw, and to extend.

This alternative interpretation would put the sculpture more in line with Lewis’s writing in Blast, which everywhere draws on the figure of the spiral to express both concentration and extension. In the incantatory poem “Our Vortex,” which concludes the long section “Vortices and Notes,” in which Lewis writes of phenomena ranging from a recent exhibition of German woodcuts to his understanding of the “just so”-ness of Chinese feng shui, Lewis lays out the fundamental principles of the Vorticist movement. On behalf of the collective, Lewis begins with a setting of the temporal contours of “their” vortex:

Our vortex is not afraid of the Past: it has forgotten it’s [sic] existence.41

Our vortex regards the Future as as [sic] sentimental as the Past.

The Future is distant, like the Past, and therefore sentimental.

…

The new vortex plunges to the heart of the Present.42

If avoiding bathetic sentimentality is paramount, then, as Nietzsche suggests in “On the Use and Abuse of History for Life,” the Past must be actively forgotten so as not to be a hindrance to action. Meanwhile the Future, because it is no more tangible or proximate (or less “sentimental”) than the Past, is likewise not to be fetishized, as Lewis insinuates it is among Marinetti’s circle. According to Vorticist logic, only the Present, into whose “heart” the “new vortex” assertively “plunges,” as though either knowing carnally or killing anti-vampirically, can be the proper home for artistic production. Put succinctly: “Life is the Past and the Future./The Present is Art.”43

The “Present” of “Art” in this sense is antithetical to “Life,” the sentimental embrace of which Lewis associates both with a residual Romanticism and with the aestheticism of a humanist critic like Cook, with whom we began this chapter. Lewis himself had already emphatically dispensed with “Life” along with “Nature” in the sarcastically titled “‘Life is the Important Thing!’” an entry that appeared earlier in the “Vortices and Notes”:

NATURE IS NO MORE INEXHAUSTIBLE, FRESH, WELLING UP WITH INVENTION, ETC., THAN LIFE IS TO THE AVERAGE MAN OF FORTY, WITH HIS GROOVE, HIS DISILLUSION, AND HIS LITTLE ROUND OF HABITUAL DISTRACTIONS.44

Romantically conceived “NATURE,” like “LIFE” for the habit-bound man of forty, is not to be viewed as a wellspring or source of invention. Consequently, the “new vortex,” notwithstanding its vital energy, is not to be confused with Life itself or Nature. Rather, this new vortex is that force that is able to escape the “groove”—avoiding the kind of mechanized repetition associated with the record player (cue Eliot and Duchamp)—and to “plunge” into the heart of the not-Life of Art in the “Present.” The Vorticist is thus conceived as an active plunger toward a “heart,” art, but the plunging always results in a casting or spinning out.

The oft-cited definition of Vorticism as the “maximum point of energy,” coined by Pound in 1913, appears in the very next section of “Our Vortex,” where Lewis returns to the figures of the Past, the Future, and Nature. But the explicitly libidinal nature of this pointed energy is made clearer when one looks at the actual line in its first appearance in poetic context:

The Past and Future are the prostitutes Nature has provided.

Art is periodic [sic] escapes from this Brothel.

Artists put as much vitality and delight into this saintliness, and escape out, as

most men do their escapes into similar places from respectable existence.

The Vorticist is at his maximum point of energy when stillest.45

Whereas “most men,” presumably the grooved men-of-forty, “escape out,” inventively, to the “Brothels” of “the Past and Future,” the singularly saintly Vorticist, steadfastly avoiding sentimentality, periodically embraces the perpetually novel energy of the now. This “maximum point of energy,” a source of vitality and delight, is contrarily accessed when the Vorticist is “stillest.”

While Lewis was the most public spokesperson of the “group,” and its most vociferous advocate, the tension between compression and bursting up, “plunging” and remaining still also appears frequently in the Vorticist writings of Pound. One of the first poems in Blast is the surprisingly tender-seeming “Before Sleep,” which describes a liminal state of somnolence, in which a speaker imagines or envisions himself “caressed” by “lateral vibrations,” the source of which is not at first described:

The lateral vibrations caress me,

They leap and caress me,

They work pathetically in my favour.46

It eventually becomes clearer that these “lateral vibrations,” which at once leap and caress and work “pathetically”—Pound had already drawn on this kind of Latinate residue in the “apparition” of the Imagist “In a Station of the Métro”—owe to the intervention of “the gods of the underworld,” whose “realm is the lateral courses.”47 So the poem features an emanation coming from below, an emanation that necessarily precedes a journey out. The second half of the two-part poem reads, in part:

Light!

I am up to follow thee, Pallas.

Up and out of their caresses.

You were gone up as a rocket,

Bending your passages from right to left and from left to right

In the flat projection of a spiral.48

“Falling” asleep, which usually takes place in the dark, is here associated with light and is conceived as a kind of flight “up” on a rocket, a vehicle of transportation that in the context of the era in which the poem was written was associated not with space exploration but with potential destruction and “brilliant visual display.”49 The speaker in the poem claims to be “up” to follow Pallas. Whether this Pallas is the titan of warcraft and husband of Styx or, far less likely, the goddess of wisdom and protectress of Odysseus, is not clarified. In either case, Pound conceives pursuing Pallas’s rocket-like flight out of “the underworld” (the zone of dead souls that, elsewhere, Pound associates with backwater America or with the British or European poetic status quo) as taking place in the “projection of a spiral.” This flat projection, its “bending” but penetrating “passages” mimicked by the suddenly expanding and then contracting line-lengths in the stanza, links the shape of superhuman power, the power to escape, to the act of writing, a fundamentally “flat” act that nevertheless here is portrayed as lifting up and out.

Toward the end of the inaugural volume of Blast, Pound offers a quasi-poem, almost redundantly called “VORTEX,” that is less lyrical and more manifesto-like, less cursive and more incantatory. Working himself into a kind of rhetorical lather, Pound returns once again to Lewis’s stilled whirlpool figure:

The vorticist relies on this alone; on the primary pigment of his art, nothing else.

Every conception, every emotion presents itself to the vivid consciousness in some primary form.

It is the picture that means a hundred poems, the music that means a hundred pictures, the most highly energized statement that has not yet SPENT itself it [sic] expression, but which is the most capable of expressing.50

The sheer potentiality of the Vorticist “statement” swamps mere poem, picture, or musical composition, artistic modes ordered in quasi-Nietzschean hierarchy of their expressivity. Amplifying the earlier “maximum point of energy when stillest” formulation, Pound here sexualizes the statement, or rather portrays it in erotic terms and desexualizes it in the mode of tantric or Kantian proscriptions against the expenditure of semen: the most highly energized statement is that which “has not yet SPENT itself” in “expression.” (A moment later, Pound juxtaposes this “Anglo-Saxon” form of manly withholding from Italian profligacy, making clear the links between Jarry and Futurism discussed earlier: “Futurism is the disgorging spray of a vortex with no drive behind it,/DISPERSAL.”)51

MANLY WITHHOLDING AND THE VORTEX OF WAR

Given that Pound goes on to call the “primary pigment in poetry” “IMAGE,” and given that Pound’s and Lewis’s 1914 notions of “maximum energy” and “stillness” share structural similarities with Benjamin’s “dialectics at a standstill” (probably first articulated around 1927 and itself offered as a sort of definition of Benjamin’s conception of “image,” one that guides this book’s argument), it behooves us to address for a moment key distinctions between the “whirlpool”-like thinking of the men. Whereas Pound, Lewis, and Benjamin each suggest the potentially redemptive dimension of stilled dialectics of the “now,” Lewis advocates a Nietzschean active forgetting of the past, while Pound’s conception of the accessible past consists largely of architecture, art, and poetry—including what Eliot, in his famous and clearly Pound-influenced essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent” will call “great poetry” or “the greatest poetry.”52 For Benjamin, who is of course also passionately invested in the idea of cultural continuity, which he asserts is impossible under massified modernity, such notions of tradition are always inflected with the remnant of the Namenlosen, unnamed and unnamable people trampled in history’s narrative of progress. This remnant informs Benjamin’s terse but poignant quasi-Brechtian statement in thesis 7 of “Theses on the Concept of History”: “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”53

Pound’s intriguing figure for the “highly energized statement that has not yet SPENT/itself it [sic] expression” can further be usefully compared with Benjamin’s own juxtaposition of “historicism” and “historical materialism” in thesis 16. For Benjamin, “Historicism offers the ‘eternal’ image of the past; historical materialism supplies a unique experience with the past. The historical materialist leaves it to others to be drained by the whore called ‘Once upon a time’ in historicism’s bordello. He remains in control of his powers—man enough to blast open the continuum of history.”54 Benjamin’s oddly macho version of the “man enough” “historical materialist” may seem out of character when considered against the lasting impression of the melancholic Berliner, hand on anguished-but-ever-thinking forehead, but it has to be acknowledged and reckoned with. Indeed, note that the verb with which Benjamin associates what ought to happen to historical continuity is aufzusprengen (to blow out or explode), which translator Edmund Jephcott rightly renders as “blast.”

Yet the distinction between Pound’s and Benjamin’s priapic versions of stasis and potentiality emerges more clearly in Pound’s “THE TURBINE,” which follows immediately after “the most capable of expressing,” as if an enjambment:

THE TURBINE

All experience rushes into this vortex. All the energized past, all the past that is living and worthy to live. All MOMENTUM, which is the past bearing upon us, RACE, RACE-MEMORY, instinct charging the PLACID,

Pound distinguishes between a passé simple and an “energized past,” one “living and worthy to live”—the latter apparently overlooked by the Futurists. This kind of past, depicted as a voracious hunter, “bears upon” and “charges” the inert, feminized future. Clearly, for Pound, though not for Benjamin, the idea of the past is inherently linked to emphatic ideas of “RACE” and “RACE-MEMORY,” ideas that, for Pound, make life “worthy to live.” Benjamin’s investment in the past is precisely the redemption of what advocates of race and race-memory consider bare or mere life (on which they act, endlessly hunting). Thus, notwithstanding its structural similarities to Benjamin’s mode of a stilled, stormy dialectics, Pound’s momentous, totalizing turbine is headed in a quite different direction.

Pound’s direction will reveal itself clearly enough in the Cantos of the following decade, especially those cantos that, like the proclamations of Italian Futurists whose ideas he had excoriated, extol the leadership of Mussolini. But the militarism implicit in Pound’s previously rather abstractly Vorticist claims, and their direct connection to the geopolitical field, are amply evident in the Blast writing of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. In the concluding entry to Blast’s first volume, Gaudier-Brzeska offers still another “Vortex,” this one consisting of a series of vortices, through which he traces, à la Oswald Spengler, but over the course of a scant few pages, the whole history of civilizations understood in part through their conceptions of sculpture. Beginning with the “Paleolithic Vortex,” in which man’s “manhood was strained to the highest potential,” Gaudier-Brzeska considers the “Hamite Vortex” of Egypt, where the “use of the vertical” inspires awe.56 The Hamites, according to Gaudier-Brzeska, in turn influenced “the fair Greek”57 and, through the Greek, the “Indians,” who “felt the hamitie [sic] influence through Greek spectacles.”58 Here sculpture was produced “without new form perception,” the result being a “Vortex of Blackness and Silence.”59 Following then-current ethnographic and proto-eugenic notions that the German race descended from these wandering, conquering Aryans, Gaudier-Brzeska asserts, “The Germanic barbarians were verily whirled by the mysterious need of acquiring new arable lands.”60 Against their veritable whirling stood the “Semitic Vortex,” where “the lust of war” flourished; sculpturally, these Semites contrarily “elevated the sphere in a splendid squatness and created the HORIZONTAL.”61

Once this Vorticist classical-civilizational racist genealogy is established, Gaudier-Brzeska, an eager student at Pound’s self-styled “Ezuversity,” shifts his attention to China, land where “THE VORTEX WAS INTENSE MATURITY,” until the arrival of the “Neo-Mongols,” with their “VORTEX OF DESTRUCTION.”62 Meanwhile, in contrast to art of the “highly developed peoples,” there are the quickly surveyed inhabitants of Africa and Oceania, where the “VORTEX OF FECUNDITY” can be found.63 Here the one great cultural gift of these “inhabitants” is offered: those “masterpieces … knowns [sic] as love charms.”64

Ultimately, harnessing the energy of all these different geographical vortices are the “moderns”: Gaudier-Brzeska ranks himself alongside Jacob Epstein, Constantin Brancusi, Aleksandr Archipenko, Xawery Dunikowski, and Amedeo Modigliani—half of whom, surprisingly, might be traced, via Poundian race-memory at least, to the “Semitic Vortex”—who, with “the knowledge of our civilisation,” have “mastered the elements.” These six “moderns” have “made a combination of all the possible shaped masses—concentrating them to express our abstract thoughts of conscious superiority./Will and consciousness are our/VORTEX.”65

Reaching the bold vortex of “will and consciousness”—“will” understood in more Nietzschean than Schopenhauerian terms and “consciousness” in more Hegelian than Nietzschean terms—Gaudier-Brzeska’s cavalcade of vortices abruptly cuts off. “Their” vortex represents the consummation of the vortices, the “VORTEX OF THE VORTEX” that Gaudier-Brzeska trumpets elsewhere in the short essay-cum-sculptural manifesto. “Will and consciousness are our/ Vortex” constitutes the essay’s terminus, apotheosis, or ne plus ultra.

And yet this was not Gaudier-Brzeska’s final word on the matter. The second volume of Blast, the “War Volume,” featured Gaudier-Brzeska’s letter from the battlefields of the Great War, where he was fighting with the French army, in which he had enlisted (and been decorated for bravery), and where he would die, giving his final words even more resonance. This missive was also titled “Vortex,” though subtitled “(Written from the Trenches),” and in it Gaudier-Brzeska, after two months of fierce fighting, still shockingly asserts with Futurist verve that “THIS WAR IS A GREAT REMEDY,” though remedy for precisely what ailment—civilizational malaise?—is left unstated.66 He stubbornly concludes by affirming, “Nothing has changed. … MY VIEWS ON SCULPTURE REMAIN ABSOLUTELY THE SAME. IT IS THE VORTEX OF WILL, OF DECISION, THAT BEGINS.”67 This “vortex,” in which will and decision are paramount because generative—what this vortex “begins” Gaudier-Brzeska again does not say—repeats with a difference Gaudier-Brzeska’s own earlier demand for “will and consciousness”; “will and decision” would presumably excise the vagaries and undecidability generated by consciousness. In a spiral, what appears to be “THE SAME” is never quite the same.

While the amateur sportsman Theodore Andrea Cook—whose enthusiastic study of spirals, published in 1914, was addressed at the beginning of this chapter—stressed the connection between spiral curves and “life,” it is clear that Gaudier-Brzeska’s vortex of “decision,” coming “from the trenches” the following year, points deathward, dragging with it untold numbers of bodies, including his own. Yet it is a kind of death that Gaudier-Brzeska insists would be generative.68 Indeed, while the issue of Blast in which his missive appears effectively marked the death of the Vorticist project, “their” blasting vortex, a result of the impulses generated over a trajectory leading from Jarry through the Italian Futurists, would send aftershocks in (at least) two opposed directions, each with a distinct historical and geopolitical sensibility. On one hand, in one land, was W. B. Yeats’s grandiose, mystical-civilizational “vision” and, on and in another, Vladimir Tatlin’s equally grandiose scientific socialism. The next chapter will trace these opposed spiral directionalities and attempt to harness their energies into a productive constellation.