Outward-Bound Cargoes

Cutty Sark was, of course, built for the China tea trade. But her core purpose was to make profits. In her lifetime she carried a vast array of goods from a wide variety of sources. But these were not only homeward-bound cargoes. Cutty Sark never left London empty-handed. Unlike her ‘bulk’ cargoes of tea and wool, her outward-bound cargoes consisted of an extensive mixture of goods, which would be described as ‘general cargo’. Among the thousands of items she carried from London were pianos, jewellery, wine, beer and brandy, candles, cocoa and cutlery.

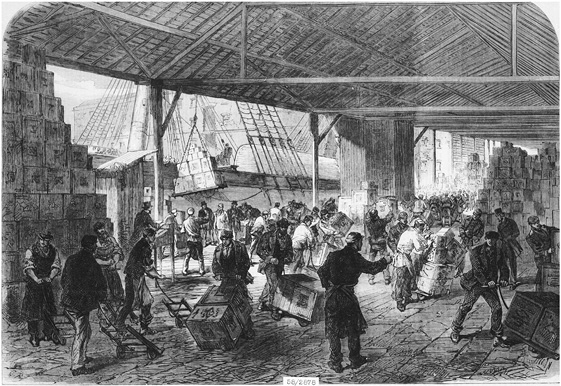

Invariably, Cutty Sark would load and unload her cargoes at the East India Docks, not far downriver from her permanent home in Greenwich. These docks opened in 1806 for the East India Company. They were composed of an import and an export dock, with an entrance basin linked to the River Thames. The docks could handle up to 250 vessels at a time, and from 1860 a rail link made access to the cargoes even quicker. As the volume of trade increased, the area became more developed, with warehouses, storage sheds, shops, pubs and cafés appearing for the benefit of the sailors and shipowners. Conveniently, Jock Willis’s home was located nearby.

Unloading tea at the East India Docks

National Maritime Museum, London (H3863)

While engaged in the China tea trade and then in the Australian wool trade, Cutty Sark took a general cargo to Australia, where she would unload before collecting a shipment of either coal for China or wool for Britain. A full breakdown of her varied cargo would be provided in Australian newspapers. Her outward-bound cargo, carried in 1874 and quite possibly catering for those recently settled in the southern hemisphere, is shown below.

3333 bars iron, 26 cases books, 35 casks wine, 173 drums oil, 170 trunks boots, 11 cases pianos, 25 cases vestas, 155 packages hardware…56 plates, 43 cases iron, 693 rails…20 cases perfumery, 4 cases machinery, 12 tanks malt, 71 cases confectionary [sic], 10 packages apothecary’s wares, 99 boxes tin, 49 hurdles wire…10 packages tobacco, 54 packets of hops…100 casks sulphur…15 casks olive oil, 1195 cases drapery, 1100 boxes candle…1462 packages.

Alcohol was often carried on board. Just over a month into her maiden voyage, with a cargo including wine, spirits and beer, Captain Moodie records a drunken incident with Able Seaman John Hanlon. The next morning, he records:

This morning I called John Hanlon into the Cabin to ascertain if possible how he came about the Drink that he got last night. But he denied having tasted any kind of drink since the Ship left London, he did not remember coming aft at all but said, that it might be a Fit that he … was subject to Fits at times. But there is little doubt that he had been drinking strong drink of some kind and there is as little doubt that it must have pilfered it from the cargo or stores.

This incident of stealing alcohol does not seem to have been an isolated event. John Lester Vivien Millet served as an apprentice on Cutty Sark in 1884. After a career at sea, he would later write his memoirs, Yarns of an Old Shellback, in which he recalls that the steward, 26-year-old Edward West, was ‘a young and very decent sort of chap, but I fear he was responsible for a good deal of pilferage’. He often shared a bottle of champagne with the apprentices, who were happy not to ask questions but horrified when they realised the total loss amounted to almost £300.

Gunpowder was an unpopular cargo with apprentice Clarence Ray. It was collected on a number of occasions from Gravesend, bound for Australian mines, and Ray wrote in one of his letters to his mother that because of the inherent danger in handling it, ‘when you are working Powder [unloading it], you can’t get any grub because the gally [sic] fire has to be put out’.

Homeward-Bound Cargoes

Cutty Sark was built to be a tea clipper. In her lifetime, she carried almost 10 million lbs of the exotic leaf. Yet she would make just eight voyages before being forced out of the trade by steamships and the Suez Canal. She would only carry tea once more in her career, from Calcutta (Kolkata) to Melbourne in 1881. This was not Chinese tea but Indian, and from the 1880s, Indian and Ceylon (Sri Lankan) tea would eclipse China and dominate the trade in Britain.

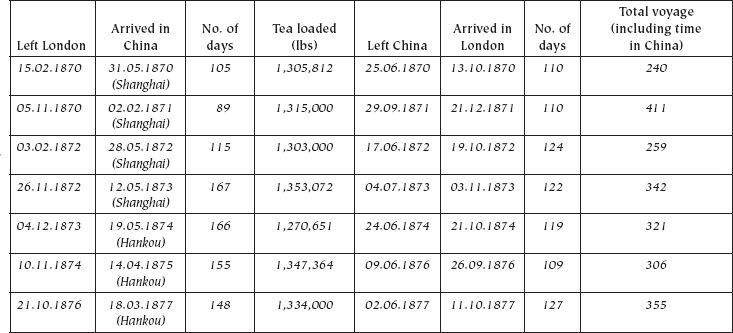

Cutty Sark’s Tea Years

Picking tea in China would begin in mid-April. A second harvest was gathered in July, but the two subsequent harvests were reserved for the domestic market. Drying was completed locally, and whether the tea was black or green would depend upon the drying method. Britain principally imported black tea, while green tea went to America. The best black teas were grown in the Fukien (Fujian) province, for which Foochow was the main port. In the 1860s, the bulk of the British tea fleet congregated here, at the Pagoda anchorage. Foochow was also the starting point of the Great Tea Race of 1866, and more than half of China’s tea was exported from there in this period. However, 25 miles up the narrow, shallow and twisting waters of the River Min, it was not easy to reach. Monkeys are said to have got tangled in the rigging of passing ships as they tried to make use of them to jump from one side of the river to the other. Foochow was also expensive: a ship of similar size to Cutty Sark paid £160 in tonnage dues in 1864. Added to towage and pilot fees, this could amount to a total of almost £650. It is for this reason that Cutty Sark concentrated instead on the ports of Hankow and Shanghai.

The interior of a tea-house, Hong Kong

Photograph by John Thomson, 1868/1871. Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London

Tea exports from China centred upon Hankow. At the heart of a number of tea districts and with a large network of inland waterways, it offered variety both in its exports and in the method of exportation. Like Foochow, however, it was not easy to reach. It was 600 miles upriver, necessitating a long and expensive tow. Because of this, it was considered to be largely inaccessible to sailing ships and became the preferred port for steamers. In what was perhaps a shrewd gamble, however, Cutty Sark’s owner decided to compete with the steamships at Hankow. In 1877 she secured a cargo of 1,334,000 lbs of tea at a freight rate of £4 5s. Her old rival Thermopylae secured a larger cargo and reached Britain in a quicker time, but having chosen to load at Shanghai, she only managed to secure a freight of £3.

For her first four voyages, prior to focusing on Hankow, Cutty Sark loaded tea from Shanghai. It was situated on the River Whangpoo (Huangpu), and in the right conditions a vessel could be navigated under canvas and without a tug. Shanghai was popular as a ‘top-off’ port where other high-value cargoes, such as silk, would be added to the tea cargo.

Tea was generally shipped from Foochow and Hankow in late May. After the tea had come down to port, the long process of valuing it would begin. Before telegraphy had reached the East, tea merchants in London might notify commission agencies such as Jardine, Matheson or Dent & Co, to instruct them as to the quantity and quality they sought to purchase. Haggling with the ‘tea men’ to agree upon a price could take up to a week. When deciding upon which ships to load first, there were many considerations to take into account, but those vessels that were judged to be capable of the quickest passage tended to be loaded first.

Loading the Ship

Skilled Chinese stevedores were employed to load the ship, a process that could take up to four days. Ballast of up to 100 tons of iron kentledge (scrap iron) and 250 tons of clean shingle would be needed to provide stability. After the ballast was laid, the stevedores would level it out and round it down to give the ship’s tiers the exact curve of the deck and beams. This was a meticulous process in which the stevedores would be able to detect the presence of even the smallest stone. The ballast would be covered with half-inch boards. Onto this, old tea or green tea would be placed before the tiers were built up. The tea chests themselves, consisting of wood with lead piping, were different sizes. ‘Congou’, a general word for black tea, and Souchong were the largest tea chests at 23 by 17 inches. Half chests and ‘catty boxes’ were also loaded to make the most of the space. Once the layers had been loaded, the work of the stevedores gave the appearance of a splendid deck, flush from stem to stern. On top of this, split bamboo in a trellis pattern, woven at a thickness of about three inches, and then canvas would sit on top. Great care was taken to ensure that the tea would be kept as dry as possible. If raw silk was to be carried, as it often was from Shanghai, this would be packed into bales, covered in matting and placed in the driest point of the ’tween deck.

Brokering a Deal

Once a price was agreed upon, the next thing would be to fix the loading freight, which would have to be decided at the beginning of each season. The master of a ship would often act for the owner to negotiate the right price. If the freights were too low, the decision might be taken to conduct more voyages up and down the coast, or even to India, to fill time before the next season commenced.

When it was known that ships had been reported in the English Channel, a great deal of excitement would ensue. Brokers acting for various consignees would rush to the docks and wait for the ships to arrive. Once they had, ships with over 10,000 chests of tea could be unloaded in as little as six hours. Samples were readily and rapidly taken and sent to those dealers whom the brokers considered would be likely to make a purchase. If the dealers’ offer was accepted, a financial transaction would take place through a broker, who would take commission from both the merchant and the dealer. The dealer would then offer his purchases at auction to a wholesaler. Most tea buyers and brokers had their offices in Mincing Lane in the City of London, once known as the ‘Street of Tea’. Such was the amount of tea that flooded the market that the tea auctions were increased from once a month to once a week.

Tramping

As we have seen, Cutty Sark was gradually forced out of the tea trade with the opening of the Suez Canal and the growing ascendancy of steamships. Tea chests carried by the steamers were often emblazoned with notices stating that they had come ‘via the Suez Canal’, thus providing assurance that they would contain the freshest tea in the trade. Clipper ships were diverted to trades in parts of the world where coaling stations were yet to be opened. For some, this meant the jute and sugar trades of the Philippines, for others, specialised commerce with India, and for some, like Cutty Sark, it meant taking whatever cargo she could find from port to port – in other words, tramping.

Owner Jock Willis was not confident that his ageing ship could still race with the best. Basil Lubbock suggests that he was deceived by the opinion within shipping circles that the tea clippers were too small for the big seas of the Southern Ocean. As a result, he took the decision to reduce Cutty Sark’s rig and send her tramping. Such a decision seems strange when it is considered that Thermopylae, a ship of very similar size, had entered the Australian wool trade as early as 1879. Indeed, Willis entered The Tweed and Blackadder in the same trade and so would have been aware of its possibilities. That he kept Hallowe’en in the tea trade perhaps indicates that he was hedging his bets and covering all trades with his fleet.

Cutty Sark’s tramping years were not a huge success, sending her across the globe with little return. The deaths of two masters and the ‘Hell-Ship Voyage’, which lasted for over two years, didn’t help matters. Once she was in the more stable hands of Master F. Moore, Willis opted to enter his ship in the Australian wool trade.

Wool Cargoes

Cutty Sark may have been built for the China tea trade but she forged her reputation as a record-breaking ship in the Australian wool trade.

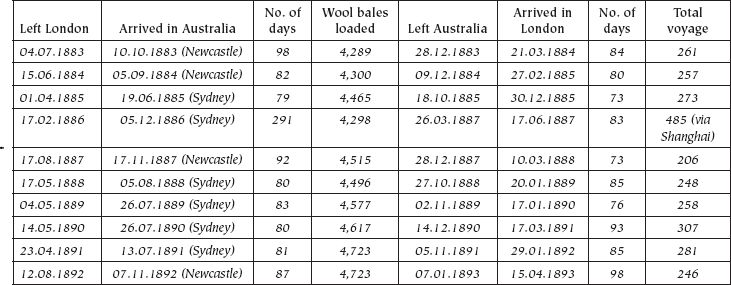

Cutty Sark and the Australian Wool Trade

By 1870 Australia had a sheep population of 42 million, surpassing Britain to become the world’s premier wool producer. Australian wool was also longer, softer and silkier than anything Europe was producing. Ships in the trade would leave Britain in the summer and return for the London wool sales in the first three months of every year. A number of clippers would berth at Sydney, Newcastle or Brisbane and await horse-drawn, wool-laden wagons. When they arrived, the wool would be loaded as quickly as possible. It would also be loaded as tightly as possible. A jack-screw press would force bales apart so that another could be squeezed in between. Captain Woodget was skilled at fitting as much in Cutty Sark as was feasibly possible. He always elected to supervise the loading himself, but in 1894 stevedores were employed to do so instead. In a keen demonstration of their skill, they managed to load over 5,000 bales, which was well over what Woodget had managed himself. Each bale was said to weigh around 400 lbs and the entire cargo would have been worth, according to Basil Lubbock, £100,000 (equivalent to almost £12 million today). As a relatively light cargo, wool offered shipowners the attractive prospect of using loading ballast that was also a profit-making cargo – namely, chrome nickel.

Cutty Sark in Sydney

National Maritime Museum, London (7366)