Cutty Sark had already come a long way since John Willis commissioned her in 1869. She was now ready to begin service, to join the great tea race, and to begin generating the profits that Willis had in mind when he discussed his plans for her with Hercules Linton.

Having sailed down the east coast of Britain after departing Dumbarton on 11 January 1870 with a temporary crew on board, Cutty Sark arrived in London on 26 January to receive her first cargo at the East India Docks. Willis had placed adverts for the outbound voyage in anticipation of the ship’s arrival using the good name of one of his other ships, Whiteadder, to ensure that a full cargo was secured. The reputation of Whiteadder was such that merchants would be more likely to trust a brand new ship with their goods, rather than relying on the good name of Willis alone. By the time Cutty Sark was in London and ready for loading, Willis had secured a general cargo bound for Shanghai of products such as wine, spirits and beer. Shortly after midnight on 15 February 1870, Cutty Sark left London on her official maiden voyage.

The Maiden Voyage

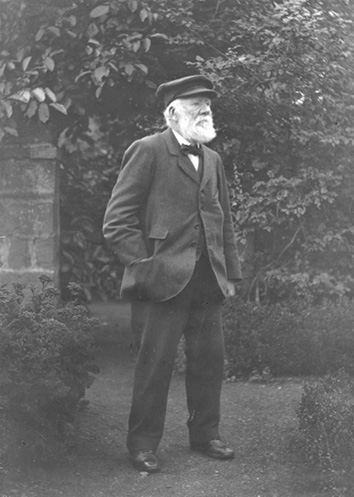

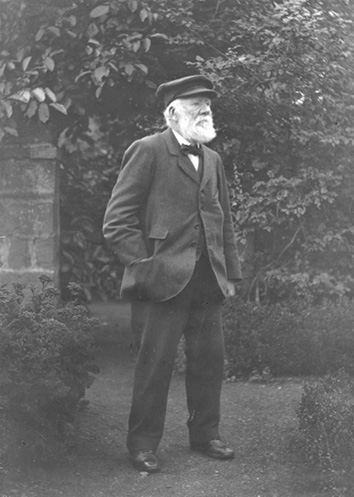

The crew for that first voyage numbered 27 in total. Cutty Sark’s first master was George Moodie, who had overseen the ship’s construction at Dumbarton and commanded her for her first three years. Moodie was one of Willis’s prized masters, serving for several years with the company and gaining a reputation as a reliable, conscientious and experienced captain under whose leadership a ship and its crew would prosper.

Crew

Moodie was served on the outbound journey to Shanghai by a crew of 26. It was one of only three voyages in Cutty Sark’s 26 years under the red ensign on which she carried no apprentices. The highest number of crew ever carried on a voyage was 30 – on the return voyage from Shanghai in 1870, and again in 1876.

Captain George Moodie

National Maritime Museum, London (7009)

The nationalities of the first crew on board Cutty Sark were very diverse, as was the case with most trading vessels of the time. However, signing crew of different nationalities inevitably resulted in cliques forming, causing friction among some of the crew and adding tension during the more difficult moments at sea. This would have a significant impact on some of Cutty Sark’s future voyages, including the return from Shanghai on this very voyage, when two crew members refused to report for duty.

Moodie’s Crew for Cutty Sark’s Inaugural Voyage

|

Crew |

Rank |

Country of origin |

|

George Moodie |

Master |

Scotland |

|

James Low |

First Mate |

Scotland |

|

James Guthrie |

Second Mate |

Scotland |

|

James Ferguson |

Steward |

Jamaica |

|

James Rae |

Cook |

Scotland |

|

Henry Henderson |

Carpenter |

Scotland |

|

Andrew Dryburgh |

Carpenter’s Mate |

Scotland |

|

William Frank |

Sailmaker |

Scotland |

|

John Korpi |

Ordinary Seaman |

Finland |

|

William Hegarty |

Ordinary Seaman |

England |

|

James Bain |

Able Seaman |

Scotland |

|

Robert Fisher |

Able Seaman |

England |

|

James Hanlon |

Able Seaman |

England |

|

Peter Swinson |

Able Seaman |

Sweden |

|

James Spears |

Able Seaman |

England |

|

John Wellesley |

Able Seaman |

England |

|

Hilton Davis |

Able Seaman |

Antigua |

|

Edward Vaughan |

Able Seaman |

Wales |

|

Charles Johnson |

Able Seaman |

London |

|

William Ambrose |

Able Seaman |

Antigua |

|

William Brown |

Able Seaman |

St Vincent |

|

James Cooper |

Able Seaman |

Scotland |

|

John Costello |

Able Seaman |

Chile |

|

Samuel Jackson |

Able Seaman |

Scotland |

|

Henrick Johnson |

Able Seaman |

Latvia |

|

Alexander Johnston |

Able Seaman |

Finland |

|

William Parker |

Able Seaman |

England |

The opportunity to sail around the world, even though it involved having to work long, hard hours, was one that many sailors relished. Upon arrival in Shanghai, however, three crew signed off and were replaced for the return voyage with five crew, at a greater cost for Willis in terms of wages than would have been the case had they signed on in London. This was to be a feature throughout Cutty Sark’s career; nearly 15 per cent of her entire crew deserted, mostly during her years in the Australian wool trade, forcing Willis to pay a premium for whatever skilled – or semi-skilled – hands the master of the ship could find at the time.

Slow Progress

Once out of the English Channel on her maiden voyage, Cutty Sark made for the Canary Islands, hitting a gale within three days of leaving London but making good time over the nine days of strong winds. It took her 12 days to reach Tenerife, whereupon she was becalmed. Once the winds picked up, Cutty Sark moved on to the wide expanse of the Atlantic Ocean. Heading for the South Atlantic, she became becalmed once again at 26°S 23°W, closer to Rio de Janeiro than to the Cape of Good Hope. Moodie’s log, while not detailed, shows his frustration at the lack of progress:

Distance 15 miles. Calm! Calm! Calm! Sea like a mirror.

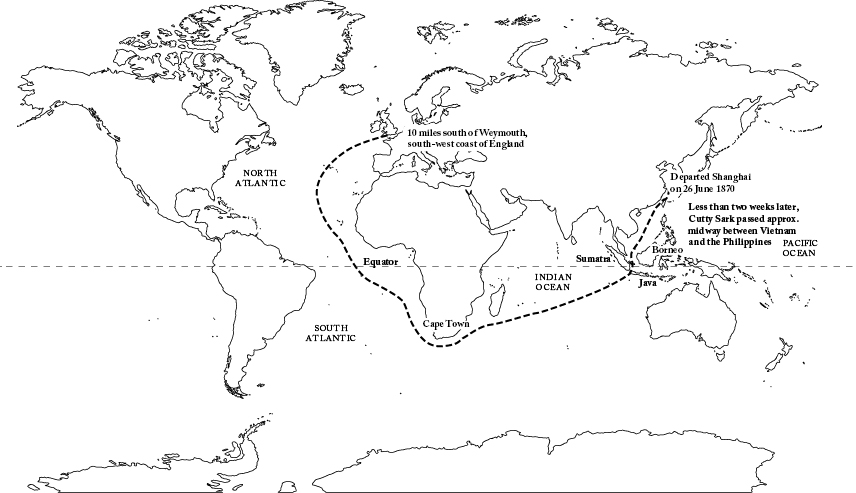

From here, Cutty Sark picked up the Roaring Forties, (latitudes 40–50° south), allowing her to breeze past the Cape of Good Hope and on towards the Sundra Strait across the Indian Ocean. Between 13 and 19 April, Moodie was able to record the following runs: 298 miles, 360 miles, 269 miles, 304 miles, 266 miles, 336 miles and 228 miles. Over the seven days she totalled 2,091 miles – a spectacular performance, and one that gave Moodie great confidence in the ship. After a brief stop at the Indonesian port of Anjer (Anyer), Cutty Sark then moved on to the South China Sea, reaching Shanghai after some three and a half months at sea. Between Anjer and Shanghai she passed Thyatira, which had left London a full fortnight ahead of her, and this was a sign of things to come.

Adjusting to Life at Sea

For any new ship, there were additional expectations of the crew. There were always bound to be issues with equipment, fixings, ropes, storage and sleeping conditions on a new vessel, and Cutty Sark was no exception. For the first two years of her life, the men were tasked with optimising the working conditions for all on board, with this first voyage requiring the most work as the rigging settled and the crew worked out the correct tensioning of the ropes and wires. While such work would benefit only the small handful of crew who served for more than one voyage, it would ultimately assist future crews in maintaining Cutty Sark’s reputation as one of the very best ships to serve on, and it is clear from her future passage times that the work carried out by Moodie and his crew on the voyage to Shanghai was expertly done.

Securing Cargo

On her later voyages, Cutty Sark sometimes spent as long as three months searching for cargo to bring back to London; in these early days, however, she spent only 25 days in China, which included unloading her general cargo from London and loading her tea cargo. Having taken on a new shingle ballast to compensate for the difference in weight after outbound cargo was unloaded, more than 10,000 tea chests were loaded onto Cutty Sark for the return leg of her maiden voyage. In these chests were some 600 tons of various blends of tea, enough to make around 200 million cups of tea; in other words, based on the census data of 1871, this one cargo alone equated to nine and a half cups of tea for every single one of the 21.4 million people alive in Britain at the time. Considering that at the same time Cutty Sark was making her first voyage there were 59 vessels bringing tea back from China, clearly demonstrating that tea was enormously popular in Britain – and that demand was not going to diminish.

This cargo, which in today’s money would be worth around £18.5m, completely filled Cutty Sark’s lower hold as well as all of the available cargo space on the ’tween deck. Willis’s agents in Shanghai secured a freight charge of £3 10s per 50 cubic feet, which no other ship that year was able to better, and which only one other ship, Serica, was able to match. This freight charge equated to a gross profit of around £2,000 for Willis – which would be the equivalent today of around £150,000. This was a considerable profit for Willis, representing a 12.5 percent return on his original investment. This means that, in addition to what he made from the outgoing cargo, around 20–22 per cent of Willis’s initial outlay would have been recouped after just one year.

Given the severe conditions Cutty Sark faced in the return journey to London, water coming through the main deck was unavoidable. To keep the tea dry, the Chinese stevedores tasked with loading Cutty Sark’s cargo packed the lower hold and ’tween deck tight with pebbles to ensure no movement between tea chests; bamboo matting was then laid over the top of the chests, and then covered again with canvas. No captain of Cutty Sark ever noted water damage to a tea cargo, meaning that these precautionary measures were clearly successful in keeping Cutty Sark’s valuable cargoes dry.

According to Basil Lubbock, the crew of Cutty Sark were among several crews in port at Shanghai taking part in a wager: the ship that made the quickest passage from Shanghai to the English Channel would win a month’s wages from each of the other ships. Considering that those other ships were Serica, Duke of Abercorn, Forward Ho, Argonaut, Ethiopian and John R. Worcester, this was a bet well worth winning. It is likely that the crews of those other ships were unaware of Cutty Sark’s intended speed and sleek design, and that her crew took advantage of those laying wagers, having witnessed first-hand her speed in the southern Atlantic a few weeks earlier. This gave the crew all the more reason to work hard for Moodie, and to get back home as quickly as the winds and currents allowed.

After loading her tea cargo, Cutty Sark departed Shanghai on 25 June. She was the first of the tea clippers to depart from Shanghai, but was already behind two other clippers, including Titania, which had a head start, having left Hankow a week earlier.

Early Tragedy

Early on the return voyage, Cutty Sark experienced her first tragedy when Able Seaman Robert Fisher became the first member of her crew to die while on active duty. Fisher succumbed to dysentery, which he may have contracted while in port in Shanghai, though he only developed symptoms once underway. Fisher suffered for some 20 days before passing away, with Moodie noting in the logbook that Fisher had suffered from the disease twice before and was of a ‘weakly constitution’. At 6.20pm on the day of his death, Fisher’s remains were committed to the sea.

As was the custom, Captain Moodie held an auction for Fisher’s personal effects. The account of Fisher’s possessions gives an indication of how Cutty Sark’s crew prepared for the conditions they were to face:

One chest, one suit blue flannel, one pair cloth trousers, one cloth vest, one pair drawers, one singlet, two pairs cotton trousers, two pairs socks, one pair stockings … one pair mitts, one pair sea boots, two caps, laid felt hat, one sou’wester, one pair braces, three linen collars, one pillow case, one razor, one pocket knife, two books, needles, thread and buttons, one palm, one sheath, one small looking glass, one comb.

With Fisher’s wages at the time of his death amounting to £13 7s. 6d., and the auction of those items above raising a further £5 9s. 10d., Moodie then sent a letter to Fisher’s only stated relative, his sister, Elizabeth. She was not easily reached, however: her address had been given to Moodie as ‘c/o John Melville of British Guiana’. The accompanying parcel contained the £18 17s. 4d. belonging to Fisher’s estate as well as the following items:

… a lock of hair, three small pieces of gold [apparently a broken earring], a small inkstand and a carte-de-visite of himself.

Costly Shortcut, Winning Voyage

After stopping briefly at Anjer on 2 August to allow letters to be sent ashore for posting, Captain Moodie took Cutty Sark across the Indian Ocean, using the trade winds to reach Madagascar. It had taken some 37 days to reach Anjer, which was around seven days slower than alternative routes would potentially have allowed. While Moodie may have been disappointed at the loss of a week’s progress, it is likely that he was attempting to calculate the quickest route home and the process lost time. It is also possible that the death of Fisher had an impact on the performance of the crew. Whatever the reason, the delay ultimately cost Willis a week but showed both Moodie and his successors that the more traditional route back from China, used by most ships in the tea trade, was the best route for Cutty Sark. Neither Moodie nor his successors ever attempted to find a shortcut on the route, staying with the tried-and-tested run that allowed the ship to make faster passages than this first voyage.

Rounding the Cape of Good Hope, she moved on to the Atlantic and finally returned to London after 110 days at sea. While it was a good performance, Cutty Sark’s passage that year was only the fourth fastest of the tea clippers and 13 days less than the year’s fastest passage by Windhover. Despite this, the crew were more interested in the wager they had laid while in port in Shanghai; Cutty Sark easily won, by some four days from Duke of Abercorn, and was surpassed only by similarly swift vessels such as her rival Thermopylae. Thermopylae had taken five days less in sailing from Foochow, setting her stall out early in the first of several ‘races’ between the two great ships; however, if Moodie had taken the traditional route home, Cutty Sark would almost certainly have beaten Thermopylae on her very first tea run. Willis was aware of the ship’s underlying performance and was pleased with her potential.

The route back from Shanghai

Return to China

Cutty Sark would prove to be a very profitable asset for Willis. One of the reasons for this was that her masters were frequently able to unload their cargo and load on her new cargo quicker than was possible for many of her rivals. Willis’s agents were also key to the process, as more often than not Cutty Sark arrived in port already contracted for her return cargo. Once back in London in October 1870 she spent just 23 days in her hometown port, departing quickly again for China with a cargo of general goods.

Moodie took a longer route on this occasion, passing Timor instead of the more westerly port of Anjer, yet the clipper ship reached China some 16 days faster than on her previous voyage. Indeed, so fast was Cutty Sark that she arrived in China before the first of the tea crop was ready for loading; this meant that Moodie could either sit in port and wait for weeks, or make use of the free time. He opted for the latter, and Willis’s agents, Jardine, Matheson & Co, secured a rice cargo from Bangkok to Hong Kong, then a cargo of poles from Foochow to Shanghai. However, those same agents, who had made Willis a good profit from those two passages, then made an unfortunate error.

The freight charge offered for the first of the tea cargoes in Shanghai was just £3 per 50 cubic feet, which was 10s. per cubic foot less than the previous year and therefore not enough to convince Jardine, Matheson & Co to agree to ship the cargo. Not wanting to waste any time, Cutty Sark was sent downriver to Foochow to pick up a cargo there instead. The rate was no better in Foochow, however, but Moodie was not inclined to return immediately to Shanghai, preferring to stay put in the hope that a better rate could be procured by waiting in Foochow. It could not, and Cutty Sark returned to Shanghai after three idle weeks in Foochow to take the original £3 rate and return to London.

A Taste of Success

After another journey of 110 days, following a similar route to the previous year, Cutty Sark arrived in London on 21 December. It was her first appearance in London for more than 13 months. Of the notable passages that year, Cutty Sark’s was still among the fastest, despite leaving much later in the year and missing some of the best winds. Titania clocked the fastest passage of 93 days, arriving much earlier in the first week of October, while Thermopylae achieved a run of 106 days and Thyatira 108 days. Those three were the only ships to surpass Cutty Sark’s tea run in 1871, and this again showed Willis that, with a better route and a dash more luck, Cutty Sark had a very good opportunity to set some fast times.

Moodie was to serve as master only once more, on a rather astonishing voyage that gave Cutty Sark her first real taste of success, albeit in the face of a disappointing failure. While he commanded other vessels throughout his career, Moodie remained in love with Cutty Sark. He once famously commented:

I never sailed a finer ship. At 10 or 12 knots she did not disturb the water at all. She was the fastest ship of her day, a grand ship, and a ship that will last for ever.

With two years’ sailing safely recorded in the ship’s logs, Moodie now knew the limitations of Cutty Sark, and had begun to get the best out of her in spite of those limitations. It would be some time, however, before Cutty Sark would again sail under as capable a master: after Moodie transferred from Cutty Sark to steamships in 1872, she passed from one master to another, never quite able to recapture those early signs of promise.

At the end of 1871, however, with two successful seasons under her belt, Cutty Sark appeared destined for many equally successful years to come in the China tea trade. Little did Willis, Moodie or her crew know then that Cutty Sark’s fate was about to be determined by one extraordinary voyage.