The Passages that made Cutty Sark Famous

1872: Shanghai to London

By 1872 Cutty Sark was becoming well known in the Far East. Her first voyages, while generating significant profits for Willis, had also been a period of settling in for the ship; the crew needed time to get to grips with how she handled, and the route to and from China needed some refinement by Captain Moodie to allow the clipper ship to achieve the best possible passage times. On her maiden voyage, her arrival back in London in 1870 after a passage of 110 days was one of the fastest of the season; it was by no means the quickest, but a new ship could not reasonably have been expected to have surpassed her rivals so soon after construction. Indeed it was not until her third tea run, having departed from London with a cargo containing yet more general goods, that she began to make a real name for herself in the tea trade.

Rivalry with Thermopylae

Jock Willis’s intention for Cutty Sark to not only rival Thermopylae but to surpass her was now about to come to pass. For when Cutty Sark departed Shanghai on 17 June 1872, her rival was sailing close behind her. What was about to take place was akin to a modern-day Formula One race, with two of the fastest vessels of the era engaging in a frantic battle to reach the finishing line of the River Thames, each with their own distinct characteristics that could affect the outcome.

Thermopylae was also a new ship, having been constructed by Walter Hood & Co in Aberdeen for the Aberdeen White Star Line in 1868. Thermopylae had achieved faster passages to and from China than Cutty Sark had; her two previous return journeys from Shanghai were 105 days and 103 days, significantly quicker than Cutty Sark’s twin 110-day passages. Thermopylae was therefore the ship to beat, and Moodie would have been conscious of the repercussions had Cutty Sark not performed well in such a close contest. Undoubtedly, the master would have been determined to please Willis, and so the crew of Cutty Sark were about to be put to their first true test – as was Cutty Sark herself. A race against the very best in the tea trade was about to commence.

The two ships were well matched. Thermopylae was also a composite-built clipper ship and her dimensions and capacity, as listed with Lloyd’s Register, were strikingly similar to those of Cutty Sark. She had been designed by Bernard Waymouth, the London senior surveyor for Lloyd’s Register, which had compiled the official rules for the construction of composite ships. Waymouth was a highly respected figure within the shipping community, and a ship of his design was always destined to attract attention.

Comparing Cutty Sark and Thermopylae

|

Measurement |

Cutty Sark |

Thermopylae |

|

Length |

212’ 5” |

212’ |

|

Breadth |

36’ |

36’ |

|

Depth |

21’ |

21’ |

|

Gross tonnage |

963 tons |

991 tons |

Thermopylae’s master was Robert Kemball, who was given command upon her launch in 1868 and who had served as master ever since. Kemball had been master of Yangtse, which had been known as a slower vessel until, under Kemball, she had beaten several ‘faster’ ships. Kemball was also the man responsible for Thermopylae’s excellent performance from the outset – including a record pilot-to-pilot passage from London to Melbourne of just 60 days in 1868–9, a record for the voyage under sail that remains to this day. With the nickname ‘Pile-on-Kemball’, Kemball and Thermopylae posed a significant challenge for Moodie. A comparison of the recent performance of the two ships, and of their captains, would have suggested that Thermopylae would have been the favourite to reach London first.

Sketch of Cutty Sark plan compared against Thermopylae plan

National Maritime Museum, London (CYS0144)

National Maritime Museum, London (MSA0170)

The Race Begins

The race between the two ships began immediately upon their departure from Shanghai, on 17 June 1872. Thermopylae, carrying approximately 200,000 lbs of cargo less than her usual load, left port two hours later than Cutty Sark, although fog and calms kept both crews on edge as the race began on a somewhat false start. It is quite possible that Kemball took less cargo to give Thermopylae as much advantage as possible against her rival. The race began in earnest on 23 June when the calms gave way to a gale that split Cutty Sark’s fore topgallant sail.

The two ships were within close distance of one another for some time, and on one occasion early in the race even hoisted their ensigns to signal the other vessel. On 26 June Cutty Sark, herself carrying a cargo weighing 20,000 lbs less than her normal load, had built up a slight lead. On 1 July Cutty Sark’s fore topgallant sail was split again by another strong gale, which then subsided into a light breeze for much of the following week.

By 15 July, Cutty Sark was around eight miles ahead of Thermopylae and was increasing her lead as they approached the Gaspar Strait, which was notoriously difficult to navigate. On 19 July both ships arrived at the port of Anjer, with Thermopylae having overtaken Cutty Sark due to challenging conditions for the latter: the passage through the Gaspar Strait had required Moodie to change course on more than one occasion to avoid waterspouts, which, had she been caught in one, would have been devastating for Cutty Sark. It was at Anjer that Cutty Sark carried out some brief business, mainly dealing with the crew’s letters. Thermopylae did not stop, and the two hours Moodie lost as a result of stopping allowed Kemball to build up a lead as the two ships left waters best suited to Thermopylae, and entered waters best suited to Cutty Sark.

Disaster Strikes

From Anjer it was a straight race back to London: across the Indian Ocean, round the Cape of Good Hope, and up through the Atlantic to the English Channel. As early as 20 July Thermopylae had extended her lead to around three miles; however, when the winds picked up, Cutty Sark soared past her, sailing more than 300 miles each day for three consecutive days. These trade winds continued to push Cutty Sark south and west, allowing her to have developed a significant lead by the time the winds calmed on 7 August.

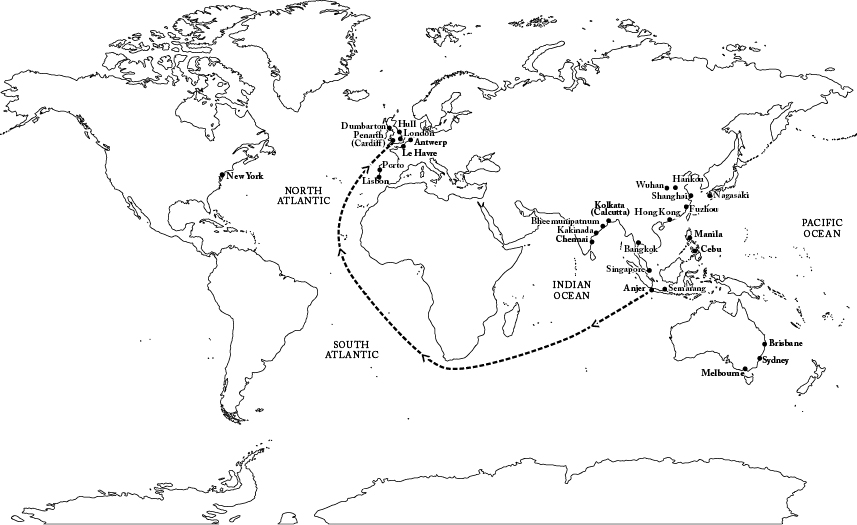

Map of route back from Anjer

When, on 11 August, a gale battered Cutty Sark off the coast of South Africa, she had built up a sizeable lead over Thermopylae – around 400 miles separated the vessels. This lead was not to last. The gale blew for four days, with some of the most furious winds Cutty Sark was ever to see during her career. They were strong enough to tear the fore and main lower topsails on 13 August, as well as to completely destroy the ship’s rudder on 15 August, leaving her unable to steer.

Saving the Ship

That same day, at a latitude of 34°26’S and a longitude of 28°1’E, Captain Moodie instructed the crew to put together a makeshift, or jury, rudder. The heaving seas made the tesk near-impossible and it would be six days before this jury rudder was finally fitted on 21 August. By the time Cutty Sark had begun to make good time again – 194 miles sailed on 23 August – she had fallen nearly 500 miles behind Thermopylae.

The jury rudder was a temporary fix designed to allow the ship to steer and thus resume her journey safely. Robert Willis, brother of Jock and the owner of 37.5 per cent of Cutty Sark, was on board, and had been opposed to the idea of the crew constructing a jury rudder, instructing Moodie instead to make for the nearest safe harbour – Port Elizabeth. Moodie was an experienced captain and knew that if he did so, any hope of finishing the voyage in a good time would disappear; indeed, it was unlikely that Port Elizabeth would be able to provide Cutty Sark with any more skilled labour or materials than the ship already carried on board. The relationship between the two men soured at this point, but it was undoubtedly Moodie’s determination to construct the jury rudder and thus continue with the voyage that contributed to one of Cutty Sark’s finest moments.

With rough seas hampering the efforts of the crew, the ship’s carpenter, Henry Henderson, set up an improvised forge on the main deck in order to fabricate the fittings required to attach the jury rudder to the stern post of the ship. In addition to the crew, Henderson was able to call on the assistance of two stowaways, one of whom, John Doile, was a carpenter, and the other was a blacksmith. The other crew member assisting Henderson was Moodie’s son, Alexander. At one point the makeshift forge constructed by Henderson was torn from the deck by the rolling seas; the fire from the dislodged forge struck the younger Moodie, causing lifelong scars.

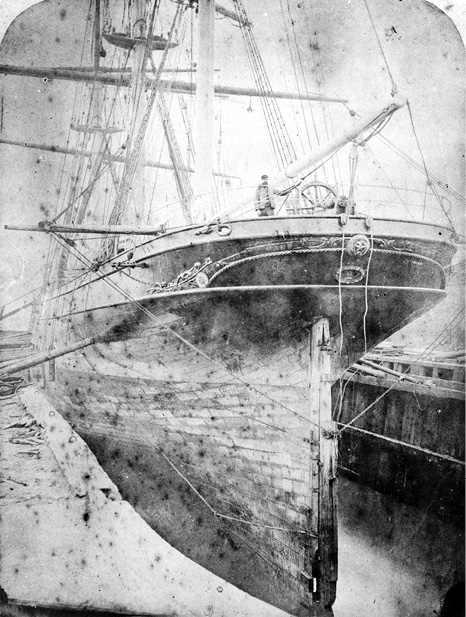

Henry Henderson with his jury rudder

National Maritime Museum, London (7795)

The four men took six days to construct the jury rudder, using one of Cutty Sark’s spare spars for the rudder post and blades, fashioning the fixings and attaching the jury rudder to the stern post. With a combination of rolling seas, wet weather and strong winds, the whole endeavour was fraught with danger. However, crews on board such vessels as Cutty Sark were well used to dealing with the elements, and that Cutty Sark was able to resume her journey again so quickly was testament to the resolve of her master and crew.

Getting Underway

Cutty Sark resumed her journey at a snail’s pace on 21 August, and Moodie was forced to take a conservative approach to the voyage as the jury rudder was not able to cope with strong winds and the accompanying heavy seas. Over an eight-day period towards the end of August, Cutty Sark sailed just shy of 500 miles. Limited to a maximum of 8–9 knots, Cutty Sark passed the island of St Helena on 9 September, some four days behind Thermopylae, and then the Equator on 15 September.

With the ship’s speed limited to ease the pressure on the jury rudder, it is surprising that the crew still managed to achieve runs of more than 200 miles on seven occasions in the first two weeks of September. However, this luck was not to last: on 20 September the jury rudder failed, leaving Cutty Sark helpless once more. A second jury rudder was constructed, using whatever spare material could be found on board, and a slower pace was kept for the remainder of the voyage.

Thermopylae arrived in the Downs off the coast of Kent on 12 October, seven to nine days before Cutty Sark limped home. If it hadn’t been for the six days lost while constructing jury rudders and the much slower pace necessitated by using the jury rudders, it is certain that Cutty Sark would have beaten Thermopylae to London by several days. It is also remarkable that, despite the lost time and limited speed afforded by the jury rudders, the passage made by Cutty Sark was not even the slowest tea run of 1872.

The Beginnings of Fame

While Thermopylae technically won the race, the accolades and praise of the shipping community went to Captain Moodie and Cutty Sark. Moodie’s achievement in limiting the amount of time Thermopylae arrived in London ahead of Cutty Sark to between seven and nine days was widely seen as more impressive than Thermopylae’s voyage of 115 days. The carpenter, Henderson, was awarded the princely sum of £50 – around £5,000 in modern terms – by Willis for his efforts, which the Board of Trade used as an example of how to fashion a jury rudder from that point on.

Sadly, it was to be Captain Moodie’s last voyage as master of Cutty Sark. His dispute with Robert Willis over the jury rudder led to his resignation upon his return to London. He moved on to steamships and was replaced as master of Cutty Sark by the former master of Willis’s ship Whiteadder, Francis Moore. Moore was not as competent a sailor as Moodie, and it was not until the appointment of Richard Woodget in 1885 that Cutty Sark once again had as talented a master as Moodie had been.

The race of 1872, laced with disaster as it was for Cutty Sark, laid the foundations for her future reputation as the greatest ship afloat. Thermopylae played her part in that, and for that reason alone should never be forgotten. Although Cutty Sark ultimately lost the 1872 race – which, because steamships now dominated the route, would turn out to be the last of the great tea races – it is to both ships’ credit that the two rivals are still regarded as the fastest ships ever built.

It was not the last time that these two great rivals would race: later in the same year, they left London 11 days apart, arriving in Melbourne exactly 11 days apart. The two would not compete seriously again until Cutty Sark joined Thermopylae in the wool trade in the 1880s.

1885: Sydney to London

Having been forced out of the tea trade by steamships, and barely making a profit of any description for a number of years, it was clear that a new path was needed for Cutty Sark, as Willis knew that her potential to generate revenue was not being achieved. He would undoubtedly have had many ambitious opportunities at his disposal around the globe, but with some of his fleet already serving in the Australian wool trade, he took the more cautious approach and entered Cutty Sark into a trade he knew well – a low-risk, high-reward industry that was already paying him handsomely. It was to be a pivotal decision in the ship’s life, and one that ultimately shaped the reputation she holds today.

In contemplating his options, Willis would have undoubtedly considered the differing economics of the tea and wool trades. The business of transporting wool cargoes was significantly different to that of transporting tea, the cargoes requiring different conditions and storage below decks, and holding differing values to their owners. The ballast used to right the ship when laden with tea generally consisted of worthless materials such as stones and shingle, while with a wool cargo, ships could use more valuable ballast. Cutty Sark was known to use chrome nickel, which doubled as a secondary cargo and brought additional revenue for Willis. It was ingenious moves such as this that allowed shipowners to generate the profits they did, demonstrating how commercially minded owners had to be to make a profit. Her entry into the wool trade, then, offered the potential for Cutty Sark to make up for lost time and to generate the kind of profits Willis had in mind when he commissioned her.

A Whole New World

Cutty Sark joined the wool trade full time in 1883, loading the first of what would be 12 wool cargoes from Australia. With Captain Frederick Moore at the helm – not to be confused with Francis Moore, Cutty Sark’s second master – she took on 4,289 bales of wool in Newcastle, New South Wales. The return journey took just 83 days, which turned out to be the fastest journey of the season of all the ships serving in the wool trade. This placed Cutty Sark among the elite cargo ships in the wool trade after just one season – indeed, it was not long before she was regarded as the absolute best of all the ships in the wool trade – and Willis must surely have then regretted the previous years spent tramping the world for cargo.

One of the reasons for her supreme success in the wool trade was the route taken by Cutty Sark back from Australia. Stronger and faster in heavy winds than in light, she was propelled back to London by the Roaring Forties, known the world over for their fearsome west-to-east winds. They took Cutty Sark through the South Pacific, past Cape Horn at the tip of South America and straight into the Atlantic. No other ship in the wool trade could have taken advantage of the strong winds the way Cutty Sark could, due in no small part to her 32,000 square feet of sail and the expert master at the helm.

In addition to this, during the passage from Australia to London, ships encountered the doldrums – a belt of low pressure around the Equator in which prevailing winds are calm – only once, rather than twice as on the route back from China. Conditions were ever changing in the doldrums, and typical delays crossing them ranged from a few days to a fortnight. Since every day spent at sea cost Willis money, the fact that Cutty Sark could return to London from Australia nearly a month quicker than she ever returned from China meant that she was able to be put to sea more often than before. Cutty Sark performed well in heavy weather, and this combined with a reduction in unavoidable delays at sea meant that she thrived on the route from Australia to London and very quickly built her reputation as the ship to beat each year.

It is therefore entirely unsurprising that the voyage of 1884 was even more profitable for Willis. Captain Moore took a whole four days off Cutty Sark’s previous best passage back from Australia, making it back to London in 80 days. Willis was so pleased with Moore’s performance that he removed him from Cutty Sark and placed him aboard his prize ship, The Tweed. Unfortunately for Willis, The Tweed suffered irreparable damage during a storm in 1888 as she was approaching the Cape of Good Hope. Totally dismasted, she was towed to Algoa Bay, two days’ sailing from the Cape, and there was blown by a gale onto the shore. By this time Cutty Sark was undeniably Willis’s flagship vessel, and the only vessel that could match her record passage achieved in 1884 was, of course, Thermopylae.

Maximising Cutty Sark’s Potential

While Jock Willis was pleased with Cutty Sark’s performance, he wanted her to be even faster in order to maximise her financial potential. By now he would undoubtedly have had one eye on the clock, as Cutty Sark was designed to last some 30 years and was now exactly halfway through her expected life. To that end, he appointed one of his rising stars, Richard Woodget, as Cutty Sark’s next master.

Captain Richard Woodget, unattributed photograph, late 1880s

b Courtesy of Mary Evans Picture Library

Woodget had impressed Willis with his handling of Coldstream from 1881 to 1885. Coldstream was an old ship, built in the same year Woodget was born, 1845, and was also as slow a ship as any in Willis’s fleet. That was, of course, until Woodget was given command. Woodget took the ageing ship and coerced every half-knot of speed out of her, returning her to profitable status and impressing a thankful Willis so much that he took Woodget to the East India Docks to appoint him as master of Cutty Sark. It was a considerable rise for Woodget, who had begun his career in 1861 and worked his way up through the ranks, moving from vessel to vessel, to become master of Coldstream in just 20 years.

Setting Records

With Woodget’s appointment, setting record passages became the norm for Cutty Sark, and some of them remain unbeaten to this day. His first voyage as master of the clipper ship was her sixteenth, and she reached Sydney in just 77 days, arriving considerably ahead of schedule on 20 June 1885. This remarkable voyage included a run of 931 miles in just three days, with several other days also seeing considerable distance covered. Of the nine ships that departed from London for Sydney, Cutty Sark was fastest of all, giving Willis an enjoyable victory over such ships as the well-known Samuel Plimsoll, as well as Sir Walter Raleigh and the iron ship Pengwern.

The return journey later in the year, with Cutty Sark arriving back in London on 30 December 1885, far surpassed the expectations of even the most optimistic spectators. This leg of her journey stands as the most famous of all Cutty Sark’s passages: a record journey taking just 73 days to sail back from Sydney. What made that voyage all the more noteworthy is that Woodget had never previously sailed round Cape Horn, and he earned great respect from the crew for doing so on this occasion.

That return journey was, of course through the Roaring Forties, which lived up to their reputation. Within a week of departing Sydney, she came up against a fierce squall that took the port-side lifeboat clear off its skids and overboard, along with all the gear stowed inside. Several sails were damaged, some beyond repair, as Cutty Sark took on significant amounts of water. Despite these horrendous conditions for the crew, Cutty Sark herself was flying: according to Woodget’s logs, she sailed some 306 miles over the course of that one day alone. It was days such as this, difficult though they were for the crew, that Cutty Sark was built for.

On 2 November, Woodget took Cutty Sark as far south as 60°47’S, which was very close to the most northern point of Antarctica (albeit significantly west of that point). The voyage took her through icebergs and storms, heavy rain, squalls and some remarkably clear skies en route to London. Woodget’s log for the journey mentions other vessels encountered, such as James Wishart and Windsor Castle, the latter of which was destined for Calcutta. It would only have been in the latter stages of the journey from Sydney that Cutty Sark would have come across other ships, as the Pacific Ocean was so vast that ships rarely saw each other while crossing it. It was only once a ship rounded Cape Horn that the crew would have seen other vessels on a more frequent basis.

The return voyage from Sydney was broken down into three distinct legs. First was the long haul from Sydney to Cape Horn; on this particular journey, it took Cutty Sark 23 days to round the Horn, a distance of more than 5,000 miles. Next came the leg from Cape Horn to the Equator, just shy of 4,000 miles, which took just 20 days to cover. This was then followed by the last stretch, from the Equator to London. Despite the comparatively short distance, this 4,750-mile leg took Cutty Sark some 30 days to cover and would undoubtedly have felt longer for the crew as they approached the end of their journey.

Seventy-three days and 14,000 miles later, Cutty Sark arrived in London in a new record time despite having faced horrendous conditions on the way. It was an astonishing achievement, and testament to the capabilities of both the ship herself and her master and crew. Cutty Sark’s great rival, Thermopylae, facing the same conditions, took a whole week longer to arrive in London.

Cutty Sark’s mast head vane

National Maritime Museum, London, Cutty Sark Collection (ZBA7752)

In 1886 Cutty Sark again comfortably beat her long-standing rival Thermopylae back to London. In recognition of this feat, Jock Willis presented her with a gilded weather vane in the shape of a ‘cutty sark’, rumoured to have been inspired by Thermopylae’s own weather vane, a golden cockerel. Willis’s show of celebration was fully merited; Cutty Sark was now at the very peak of the wool trade and had no serious rival. With Woodget continuing to serve as master, Willis as invested in the ship as he ever had been, and business booming, Cutty Sark was finally achieving what Willis had intended all along. Her commercial performance was strong, and her reputation was now far-reaching. It may have taken 16 years to achieve, but Willis now had the ship he had dreamed of, and she was in a position to build on her successes. The coming years were to be an exciting time for both owner and crew.