With the number of steamships serving the China tea trade steadily increasing since Cutty Sark’s launch in 1869, it was only a matter of time before Jock Willis would have a difficult decision to make. Unfortunately for Willis, the decision was made for him by the events of 1878.

Bound for Hankow

Departing London on 3 November 1877 under the command of William Tiptaft, Cutty Sark was bound for China via Sydney for her ninth season in the China tea trade. Tiptaft had been appointed master of Cutty Sark in 1873, following on from Francis Moore, who commanded her for one voyage in the wake of George Moodie’s resignation in 1872. Having already successfully completed five tea voyages for Willis, Tiptaft was considered a safe, dependable master, someone whom Willis trusted to bring cargo back from China in a quick but ultimately secure manner. The cargo on the outbound voyage was once again a general cargo, and included a variety of items, as the demand for quality British merchandise was high all over the world.

Cargo Aboard Cutty Sark on 1878 Outbound Voyage

|

Kegs of nails |

643 |

|

Bundles of wire |

387 |

|

Cases/casks of wine and spirits |

310 |

|

Boxes of candles |

300 |

|

Anchors |

67 |

|

Chains |

27 |

|

Other packages |

11,000 + |

No sooner had Cutty Sark reached the English Channel, however, than she ran into a huge gale. Over the course of the next two days, she lost both her anchors and cables, colliding with two other vessels and requiring a rescue from two small tugs. She returned to London for repairs, departing for China once again on 2 December, a full month later than originally scheduled. The late departure was to play a significant role in the events of the coming months.

When Cutty Sark finally arrived in Sydney on 13 February 1878, the Sydney Morning Herald made note of her performance:

Among the splendid fleet of vessels sailing out of the port of London … the clipper Cutty Sark is one of the foremost, particularly as regards speed. While employed in the China trade she placed her name on more than one occasion in the premier rank, and she still would appear to be keeping up her prestige … this vessel has made the crack passage of the season viz. 72 days.

For a ship that had struggled to perform to expectations, such a fanfare would have been the perfect fillip for her owner and crew. Little were they to know, however, that the next few months would be some of the most challenging of Cutty Sark’s career so far.

Tea Shortage

From Sydney, Tiptaft took Cutty Sark up to Hankow, arriving in May 1878. Due to her late arrival, there was only enough tea left in Hankow to fill up half of Cutty Sark’s hold. Tiptaft thus elected to make for Shanghai, where he was again unable to find enough tea to fill her hold. There were two reasons for the lack of tea: one was the month-long delay in departing London, in which time much of the available tea would have been procured for the ships ahead of Cutty Sark; the other was that steamships had now taken such a hold on the tea trade that sailing ships like Cutty Sark were simply no longer guaranteed tea cargoes, as they had been for so many years. With the Suez Canal now allowing steamships to take more than 3,000 miles off the return voyage to London, and steamship design developing over the years to allow more cargo to be stored, ships such as Cutty Sark were slowly being squeezed out of the trade – a sad fact that would by now have been clear to Tiptaft.

Tiptaft’s Last Voyage

After spending so long at sea, and needing to find a cargo to make the additional sailing worth his while, Tiptaft went on to Nagasaki in Japan, hoping to secure a coal cargo; he then planned to return to Shanghai in the hope that the delay would allow time for new tea cargoes to have been delivered to Shanghai’s docks by the time they arrived back there. However, this was to be Tiptaft’s last voyage; he fell ill on the return leg, passing away on the same day Cutty Sark arrived back in Shanghai, on 12 October 1878.

Tiptaft’s death at the age of 35 left Cutty Sark in a very difficult situation. She was thousands of miles away from her home port, could only find half a cargo of tea for her hold, and seemingly had no prospects of more tea becoming available. On top of all that, she now had no master and, having over the years faced some of the worst storms any ship could weather, Cutty Sark was now facing her most dangerous test to date.

End of an Era

James Wallace, Tiptaft’s first mate, was promoted to master and immediately made for Sydney for another coal cargo bound for Shanghai. Wallace intended to then pick up more tea and make for London. It was a desperate tactic, as Cutty Sark had by now spent more than a year in the Far East, and had already twice been unable to secure a sizeable enough tea cargo to head home. Unsurprisingly, upon Cutty Sark’s return to Shanghai there remained no tea available. After several passages around the Far East, it was now June 1879, more than 18 months since Cutty Sark had originally departed from London for what was expected to be another straightforward tea run.

Cutty Sark’s days in the tea trade were now essentially over. Willis’s agents in the Far East were left with little choice but to take an irregular stream of contracts to cover costs and to keep the ship in use and maintained. This marked a new era in the history of Cutty Sark and was a period of considerable insecurity for Willis, his agents and the crew. Some of her voyages over the next five years saw her less than half-loaded with cargo; she was also to carry her last-ever tea cargo in 1881, taking tea from Calcutta to Melbourne.

Telegraphy

None of this would have been possible without the complex network of telegraphy that had been set up between Britain and the Far East over the preceding decades.

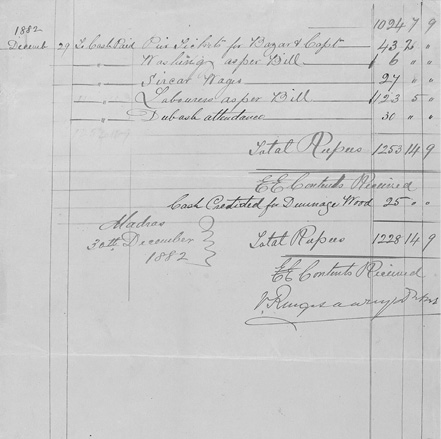

Telegram receipt

National Maritime Museum, London (LUB/12)

The telegram had been invented around four decades earlier by Samuel Morse, and it transformed the world. Communication was now possible from America to Britain, from Britain to China, and to many places in between. The system used Morse code, named after its inventor, to replace the letters of the alphabet with a series of dots and dashes. A message would be translated into Morse code, transmitted, then translated back into English; this was originally done in the form of marks on paper, but was eventually improved as operators receiving the message could decipher Morse code by listening on the receiver for the clicking. The message was sent through telegraph wires laid at the bottom of the sea, and was picked up at the other end in a matter of moments. This pioneering technology allowed Jock Willis to send messages to his agents all over the world quickly, rather than by much slower post – on average, a letter to Shanghai took around two months to arrive. Telegraphy changed the known world and allowed business owners such as Willis to capitalise on opportunities as they came up, rather than relying on agents on the other side of the world to make decisions on their behalf.

Early Tramping Days

The difficulties of tramping – carrying and delivering cargo wherever it was available, and not following any regular route – were already becoming evident to Willis. While the other ships in his fleet would likely have experienced some element of tramping throughout their careers, none spent as much time floundering for cargo as Cutty Sark. Already she had spent nearly a year longer at sea than she ought to have done, and had carried relatively little cargo during that time. The business of tramping for cargoes, while providing the means to keep a ship going, was neither profitable for the owner nor strategically sound in the long term. The risks associated with going from port to port, single cargo after single cargo, could see even a ship with Cutty Sark’s reputation become obsolete. A regular market of goods was needed, rather than risking such a valuable asset as Cutty Sark on the comparatively trivial profits generated by tramping.

With no hope of filling her hold with tea, Wallace left Shanghai on 12 June 1879 and made for Manila in the Philippines. Her hold filled with jute, and after a delay of some three months in port, Cutty Sark moved on to New York, her first foray into the North American market. The voyage took 111 days, taking the ship into unfamiliar waters and allowing the crew to experience new horizons.

New York

New York at this time was a thriving harbour, with 60–70 per cent of all imports to the United States coming through the city. As the pre-eminent city on the east coast of North America, it had become a hub for immigrants from all over the world, including Europe. It was also expanding its cultural influence, with Broadway and Times Square in particular becoming ever more popular and renowned. Cutty Sark is believed to have moored in the South Street quays, near Brooklyn Bridge, where only the most famous and important ships were permitted to berth.

The great East River suspension bridge, connecting the cities of New York and Brooklyn. Parsons & Atwater, del. New York. Published by Currier & Ives, c.1874. Image courtesy of Library of Congress

With the city’s textile industry growing exponentially, Cutty Sark’s cargo of jute, a cheaply produced natural fibre, was a good way for Willis to get back into profit, albeit not nearly enough to make up for the lack of income brought in by the ship over the previous two years. After delivering his cargo, Wallace was instructed to take a cargo from New York across the Atlantic and back to London. Cutty Sark left New York on 14 February 1880, and arrived back in London on 9 March. The passage of 19 days from New York to the mouth of the Thames was the year’s best passage by three days.

Home Sweet Home

Cutty Sark’s return home came 858 days after her aborted departure from London in November 1877. It was much needed. Such a long time away had meant that Cutty Sark was in dire need of maintenance; she spent more than two months being refurbished before setting sail in May 1880 for Penarth in Wales, to collect another coal cargo destined for Japan.

During these two months, Cutty Sark had her lower masts cut down by 9½ feet, along with a similar proportion being removed from her upper masts; her yards were also shortened, by 7 feet on the lower yards and by a smaller amount on the upper yards. This meant that she required a smaller crew on future voyages, but also meant that she lost some speed when sailing in light winds. It was a compromise Willis would gladly take, as Cutty Sark spent most of her time in strong winds, and the savings made, in terms both of maintenance and of pay for the seven or so crew who were no longer required, more than outweighed any lost time.

Hell-Ship Voyage

Throughout Cutty Sark’s career no other voyage was to cause as much controversy, or tragedy, as the voyage of 1880. Known as the ‘Hell-Ship Voyage’, and detailed in the next chapter, it resulted in the manslaughter of one member of the crew and the suicide of the ship’s first master on the voyage, James Wallace, and some exceptionally difficult times for Cutty Sark’s crew.

The ‘Hell-Ship Voyage’ took Cutty Sark not to Yokohama in Japan, as originally intended, but instead to Anjer, and then on to Singapore. In Singapore she welcomed on board her fifth master, William Bruce. Bruce was the least effective, and least popular, of all Cutty Sark’s masters, and caused significant hardship to his crew as well as to the pocket of Jock Willis. Maintenance of the ship was not carried out to a sufficient standard under Bruce, and Willis was not able to replace the necessary stores Cutty Sark required due to the losses he incurred during Bruce’s tenure.

The Crew Replaced

After a handful of cargo runs in the Far East, from Singapore to Calcutta (Kolkata) in India, to Melbourne in Australia, to Cebu in the Philippines and on again to New York, Cutty Sark came to the end of a tumultuous period lasting 697 days since she had left London to pick up Welsh coal bound for Japan. A furious Willis removed Bruce as master of Cutty Sark upon arrival in New York, and replaced the entire crew with the crew of his most reliable ship, Blackadder. With her crew now turned over to her sister ship, Blackadder sat in New York until 16 May 1882, some six weeks after first arriving in New York from Shanghai. For Willis to sacrifice Blackadder’s earning potential for that of Cutty Sark showed that, despite her recent troubles, Cutty Sark remained at the very forefront of Willis’s fleet.

Blackadder’s crew had included Frederick Moore, who now became the sixth master of Cutty Sark. Though he didn’t know it, Moore was about to usher in the greatest era in Cutty Sark’s history, as she had one final tramping voyage left in her before her fortunes were to finally turn. She left New York under Moore’s command on 4 May 1882, bound for Australia with a cargo containing nearly 27,000 cases of paraffin oil, totalling more than 120,000 litres. On arriving at Anjer – which was to be destroyed the following year by a tsunami caused by the eruption of Krakatoa – Moore received word from Willis to change course and instead head for Semarang in Indonesia.

Home Once More

From Semarang, after a stop of six weeks, Cutty Sark sailed to Madras (Chennai) without cargo, then on to Bimlipatnam with a cargo of palm sugar and redwood. From there, Moore took her on to Kakinada in India with a cargo that included more than 4,000 buffalo horns. Returning from India with another cargo of general goods, Cutty Sark arrived back in London in June 1883. It was only the second time in six years that she had spent time in her home port, where she had been berthed for just 65 of the previous 2,008 days. This was to be Cutty Sark’s last general cargo bound for London, and it included 115 bales of deer horns and nearly 5,000 bags of myrobalans, or cherry plums, to be used for dyeing fabric.

The years of tramping around the Far East for cargo had proved difficult for Willis’s agents. With regular tea runs, the process of securing cargoes had been relatively straightforward, but with Cutty Sark sailing from port to port without a long-term strategy, Willis’s agents were forced to coordinate plans from diverse ports around the world, which, even with the innovations in telegraphy, would have proved challenging. Cutty Sark was forced to spend more time in port than was normal, reducing her earning potential and allowing standards aboard to slip.

Lost Earnings

On the first round voyage of her tramping years – the 771 days from London through to her first arrival in New York – Cutty Sark spent more than 350 of those days, or nearly half of them, in port. This was due to the difficulty in securing a tea cargo and the untimely death of William Tiptaft, as well as the general delays in loading and unloading cargo. On the second long voyage of the tramping years, covering the 697 days between her calls to New York, she spent around 300 days in port, again due to difficulties involving cargo and also due to the replacement of crew. On her third and final leg, from New York to London via India, she spent around 140 of the 394 days of the voyage in port. Willis could not allow this trend to continue, as the longer a ship spent in port, the less cargo she transported, and the less effective her crew became as they grew more accustomed to the relative luxuries afforded on shore.

Cutty Sark’s Tramping Years

|

Voyage |

Master |

Departed |

Arrived |

Cargo |

|

11th |

J. S. Wallace |

Sydney 18.03.1879 |

Shanghai 02.05.1879 |

1,150 tons Wollongong coal |

|

11th |

J. S. Wallace |

Shanghai 12.06.1879 |

Manila ?.07.1879 |

Shingles (in ballast) |

|

11th |

J. S. Wallace |

Manila (Philippines) 23.09.1879 |

New York 12.01.1880 |

Unknown |

|

11th |

J. S. Wallace |

New York 13.02.1880 |

London 09.03.1880 |

Ballast |

|

12th |

J. S. Wallace |

London 13.05.1880 |

Penarth (Wales) 22.05.1880 |

Ballast |

|

12th |

J. S. Wallace |

Penarth 04.06.1880 |

Anjer 22.08.1880 |

Coal (amount unknown) for American fleet |

|

12th |

J. S. Wallace |

Anjer 05.09.1880 |

Anjer 12.09.1880 – ship turned back for Anjer following Wallace’s suicide on 9 September |

Coal (amount unknown) for American fleet |

|

12th |

William Bruce, joined the ship in Singapore |

Anjer? Received instruction from John Willis to proceed to Singapore |

Singapore 18.09.1880 |

Coal unloaded onto SS Glencoe |

|

12th |

William Bruce |

Singapore? |

Calcutta 11.11.1880 |

Ballast |

|

12th |

William Bruce |

Calcutta 05.03.1881 |

Melbourne 14.05.1881 |

Jute; castor oil; Indian tea and mail |

|

12th |

William Bruce |

Melbourne 05.06.1881 |

Sydney 15.06.1881 |

Ballast |

|

12th |

William Bruce |

Sydney 02.07.1881 |

Shanghai 17.08.1881 |

110 tons of coal |

|

12th |

William Bruce |

Shanghai ? |

Cebu 31.010.1881 |

Ballast |

|

12th |

William Bruce |

Cebu 06.12.1881 |

New York 10.04.1882 |

Jute |

|

13th |

Frederick Moore |

New York 04.05.1882 |

Semarang 20.08.1882 |

26,816 gallons of case oil |

|

13th |

Frederick Moore |

Semarang 05.10.1882 |

Madras 07.11.1882 |

? |

|

13th |

Frederick Moore |

Madras 28.12.1882 |

Bimlipatnam 08.01.1883 |

3,310 bags of jiggery (palm sugar); 100 tons of redwood |

|

13th |

Frederick Moore |

Bimlipatnam 21.01.1883 |

Kakinada ? |

6,240 bags of myrobolans (a kind of dye nut); 4,163 buffalo horns |

|

13th |

Frederick Moore |

Kakinada 31.01.1883 |

London 02.06.1883 |

4,781 bags of myrobolans; 115 bales of deer horns |

A New Dawn

After five long years of tramping, Willis was about to take a calculated gamble with the future of Cutty Sark. There is no question that the previous five years had yielded the ageing owner little by way of profit, and had almost certainly cost him more than he had earned. Cutty Sark was now nearly 15 years into her career, halfway through her original life expectancy, and Willis needed her to generate the profits he had always intended when he commissioned her. His next move was to usher in the era for which Cutty Sark would become most famous. Following in the path of another of Willis’s ships, The Tweed, Cutty Sark was about to enter into the Australian wool trade, and in so doing ensure enduring fame throughout the world.