Today, it is difficult for us to imagine what life on board a working sailing ship would have been like. Associations with a ‘bygone’ age may also prevent us from appreciating the ordered and complex machine Cutty Sark would have been. The average size crew for Cutty Sark in her tea years was 28 men. After the ship’s rig was reduced in 1880, her average crew was just 22. To man 11 miles of rigging, a maximum of 32 sails and a full sail area of 32,000 square feet in the face of merciless and relentless weather conditions required grit, determination and organisation.

Crew Responsibilities

The ship’s captain, the master of the ship, was a qualified officer with ultimate responsibility over the vessel. Each master was appointed by the owner, Jock Willis, and assumed charge over navigation, managing the crew and sourcing, loading and unloading the cargo.

Seven men served as masters of Cutty Sark in her 26 years as a British ship. They came from varied backgrounds and brought different strengths to their service. But each had progressed through the ranks of the merchant marine to become master mariners. Examinations and a system of certification were introduced by the Board of Trade in 1845 but did not become compulsory until 1854. For a fee, a mariner could make an application to be examined to attain, first, the position of second mate, then progressing on to first mate and finally master. In the earlier years of certification, those who had proof of their experience as masters were issued with a Certificate of Service and were excused from sitting exams. Certificates of Competency were issued to those who had passed their examinations, including all of the masters of Cutty Sark.

The majority of Cutty Sark’s masters appear to have been ambitious and talented young men. On average, it took them just three years to progress from second mate to master, with four of her masters achieving that position before the age of 30.

Cutty Sark’s Masters

|

Master |

Background |

Voyages |

|

George Moodie |

Born in 1831 in Fife. George Moodie oversaw the building of Cutty Sark. He was 39 when he took command of the ship for her maiden voyage. His wife christened the ship. |

1–3 (1870–72) |

|

Francis W. Moore |

Born in 1822 in Yorkshire. He was 50 when he took over from Master Moodie. He served on Cutty Sark for one voyage. |

4 (1872) |

|

William E. Tiptaft |

Born in 1843 in East London. He was 30 when he took command of Cutty Sark and served for six voyages. He fell ill when the ship reached Shanghai and died shortly afterwards in October 1878. |

5–10 (1873–78) |

|

James Smith Wallace |

Born in 1853 in Aberdeen. He was 25 and serving as Tiptaft’s first mate when he took command of the ship. Master Wallace committed suicide in September 1880 after the ill-fated ‘Hell-Ship Voyage’. |

10–12 (1878–80) |

|

William Bruce |

Born in 1838 in Aberdeen. Bruce was signed on to command Cutty Sark at Singapore, following Wallace’s death. He is generally thought to have been incompetent and was subsequently suspended. |

12 (1880–82) |

|

Frederick Moore |

Born in 1839. He was 43 when he was appointed master. |

13–15 (1882–85) |

|

Richard Woodget |

Born in 1845 in Norfolk. Woodget was 40 when appointed as master. He is generally acknowledged as Cutty Sark’s most successful and famous master. |

16–25 (1885–95) |

First and second mates provided support to the master. Both would be qualified to stand watches, take command of the ship when the master was not on deck and supervise the crew. Not all men signed on at their most recently attained rank. James Smith Wallace, for instance, had achieved his Master’s Certificate in October 1877, but the next month he signed on to Cutty Sark as first mate. Following the death of Master Tiptaft, Wallace was the most qualified man on board and was duly promoted.

Cutty Sark rarely employed a third mate. Of the seven to serve, five were apprentices, nearing the completion of their four-year indenture. Similarly, a sailmaker served on 12 of Cutty Sark’s 25 voyages and a bos’un on only seven. The former was responsible for mending the sails and all canvas work, while the latter bore responsibility for the general condition of the ship. It seems, therefore, that the crew of Cutty Sark were expected to ‘muck in’ and compensate for the absence of more suitably qualified men.

Of the petty officers, the carpenter and cook were roles of vital importance and positions that Cutty Sark always filled. The carpenter was responsible for the maintenance of the ship’s hull, rudder, masts and yards and for keeping the decks watertight. The cook produced all of the crew’s meals. Both were located in the forward deckhouse – the carpenter in his narrow workshop and the cook in his galley-kitchen.

Able seamen made up the majority of the crew on Cutty Sark. They were men who had several years of experience and a certificate to prove their competence in steering, working aloft in the rigging and handling sails. On average, 13 able seamen served per voyage. They ranged in age from 18 to 54 and came from all over the world.

Ordinary seamen were men with little or no experience of life at sea. They would complete the more menial tasks on board such as cleaning or painting. A couple of ordinary seamen served per voyage in Cutty Sark’s tea trade years. After that, hardly any served again. Instead, the number of apprentices taken on rose dramatically. In her tea years, a maximum of four apprentices served on every voyage. In her wool years, between five and nine served. As we have seen, both John Willis and Richard Woodget were shrewd operators. Given that apprentices were not paid for their service, it seems more than coincidental that the number of paid crew should drop while the number of unpaid apprentices rose. It certainly appears from the accounts of apprentices who served on Cutty Sark that rather than ‘learning the ropes’ they were often given the more menial tasks that others would not do.

A steward was employed for the majority of Cutty Sark’s voyages and was responsible for looking after the officers, serving their meals and maintaining their quarters at the stern of the ship in what was known as the Liverpool House. Often they would also help on deck, controlling the ropes of the sails and filling in where others were not available. Three ‘boys’ also served on the ship, gaining experience and being given free passage and a minimal wage before being discharged in the port of destination.

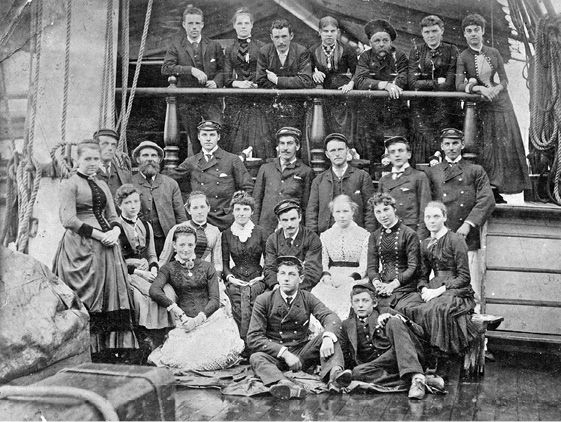

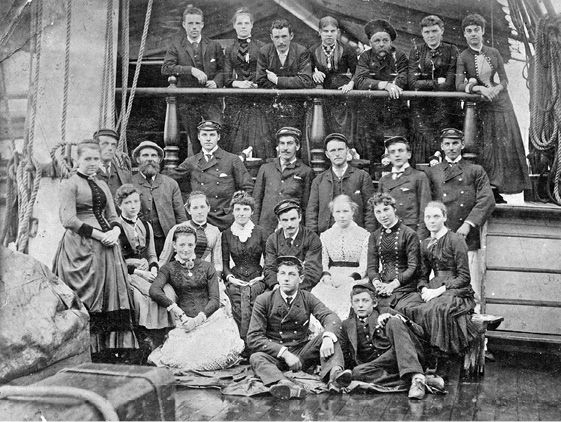

Captain Woodget, crew and friends on board, 1887

National Maritime Museum, London (A5473)

Apprentices

The Merchant Shipping Act of 1823 deemed that all vessels over 80 tons were obliged to carry at least one apprentice. In Cutty Sark’s day, apprenticeships in a vast array of occupations were a means of securing a trade for a young person. For many, there was little choice in what this trade may be. Apprentices in the merchant marine signed a four-year indenture (or contract) with a particular line, shipowner or master. Premiums for this service were fixed at what an individual thought he could persuade a parent or sponsor to pay. It could range from £20 to £100 for the four-year period. Apprentices agreed to serve ‘dutifully’ for the duration and in return they would be cared for and, in theory, gain experience that could set them on course for a career in the merchant marine.

The Marine Society was the world’s first charity dedicated to seafarers. It was founded to prepare poor or destitute boys for a life at sea. The boys were provided with clothing and received tuition on board the training vessels such as HMS Warspite (1862–76) on the Thames while waiting for a shipowner or master to apply for them to undertake an indenture. One Marine Society apprentice served under Jock Willis on The Tweed and another on the Hallowe’en. No records survive as to why he made that decision or decided not to take on any more for Cutty Sark, but perhaps we can infer that the experience was not a positive one and put paid to Willis’s charitable instincts.

Pay

Crew Lists and Agreements exist for all of Cutty Sark’s voyages. These state crew names, origins, their last ship of service, their ranks, their pay and the amount of food they should expect to receive on a daily basis. The list had to be signed or initialled by each man joining. It is estimated that 82 men (or 12 per cent) of the total to serve on Cutty Sark were unable to sign their own name. What the lists do not record, however, is how much each master earned. It seems highly probable that as this was a document that all men were expected to view (and the vast majority would be able to read), the wage of the master was deemed too sensitive to be readily available. Basil Lubbock suggests that Master Frederick Moore (1882–85) was paid £200 per year, but his source for this information is uncited. The average adult male wage in the UK in the 1880s and 1890s was £56 per annum. If we take Lubbock’s suggestion as fact, it would seem that the role of master mariner was an economically comfortable one. But what of the rest of the crew? The wages paid to ordinary seamen, able seamen, a petty officer (in the form of the ship’s cook) and the first mate are given in the table ‘Wages Paid by Rank’.

Wages Paid by Rank

|

Voyage number |

Ordinary seaman |

Able seaman pay |

Cook pay |

First mate pay |

|

1 (1870) |

£2-0-0 per month |

£2-10-0 per month |

£3-10-0 per month |

£8-0-0 per month |

|

5 (1873) |

£2-15-0 per month |

£3-5-0 per month |

£4-0-0 per month |

£8-0-0 per month |

|

10 (1877) |

£2-10-0 per month |

£3-5-0 per month |

£4-5-0 per month |

£8-0-0 per month |

|

15 (1884) |

£2-0-0 per month |

£3-0-0 per month |

£4-0-0 per month |

£7-10-0 per month |

|

20 (1889) |

No OBs served |

£3-0-0 per month |

£4-10-0 per month |

£7-0-0 per month |

|

25 (1894) |

No OBs served. |

£2-15-0 per month |

£4-10-0 per month |

£5-0-0 per month |

On average, Cutty Sark was at sea for more than ten months at a time. On this basis, an able seaman in the 1880s would have earned £30 for one voyage. Likewise, an ordinary seaman would have earned £20, the cook £40 and the first mate £71 for the same period. The better-paid men on board often allotted some of the wages, presumably to dependents at home. Very few allotments were made by the lesser-paid men. An able seaman was a skilled worker, comparable, perhaps, to a miner. It is estimated that a miner, in the same period, would have earned £4-16-0 to an able seaman’s £3-0-0. However, the latter would have been away for many months at a time, with scant opportunity to spend his wage. Furthermore, he did not have to worry about board for his time at sea. Perhaps, also, the prospect of seeing some of the world served as a useful lure, attracting some men away from better-paid occupations.

Joining a Ship

A man joined a ship by, first of all, combing the docks and identifying his preferred vessel, and then going along to see the master or first mate. He might already be familiar to the officers, or he could present his Certificate of Discharge to account for his credentials. This certificate served as a reference. It listed the last voyage a seaman undertook, on which ship, and his rank; at times, it would also provide a character reference. If the officer was happy for the man to join, he would instruct him to be at the local Shipping Office to sign the Agreement and Account of Crew, also known simply as the Crew List. If a master was particularly fortunate and there were more men in dock than ships, he could place an advert – most likely at the bottom of the ship’s gangway – and then take his pick from those who had expressed an interest. Often, however, this was not the case and a master had to make the best of the crew he had. On a number of occasions, men were demoted, either due to an instance of bad behaviour or because their skills did not match their claims. On Cutty Sark’s maiden voyage, Charles Johnson signed on as bos’un. He was almost immediately re-rated as an able seaman on the grounds that he did not understand the job.

Others appear to have chanced their arm. On Cutty Sark’s third voyage, 19-year-old Robert Williams from Liverpool attempted to join the crew at Gravesend. According to Moodie’s log, ‘He says that his clothes are on board but that he has no discharge to show what capacity he served in his last ship.’ Master Moodie decided to give him the benefit of the doubt. It was a decision he soon regretted. Two months later, he wrote: ‘I find that Robert Williams who presented himself to be an AB [able seaman] is quite incapable of filling that station.’ Williams was demoted to ordinary seaman, went missing for four days once they had arrived in Shanghai and was discharged once they returned to London.

The apprentices, like the rest of the crew on Cutty Sark, were from varied backgrounds and found their way to an indenture by differing means. If personal recommendations could not be relied upon, parents or masters could place an advert seeking an Agreement. Alexander Moodie, son of Cutty Sark’s first master, was the first apprentice to serve on board the ship. Three of Richard Woodget’s sons (Richard John, Harold and Albert Sydney) also served as apprentices. For others, a life at sea symbolised freedom and adventure. For John Lester Vivian Millett, who joined Cutty Sark in the third year of his indenture at the age of 19, a life at sea represented freedom and adventure. His father had died when he was just six, leaving his mother with four children to care for. Though enrolled at a naval school at the age of 15, Millett nagged his mother to allow him to leave school and go to sea. His persistence paid off. A chance meeting between his mother and the shipowner Richard Ellis secured Millett an apprenticeship for an unspecified amount, and his dream was realised. Millett would go on to achieve his Master’s Certificate at the age of 28 and enjoyed a life at sea, publishing Yarns of an Old Shellback in 1925.

Not all apprenticeships guaranteed a career in the merchant service. Clarence Ray was 16 when he joined Cutty Sark in 1894. Born in North London, Ray and his family had moved to Hastings when he was small. Like Millett, his father, who had been a merchant, had died. Clarence’s mother secured a clerk’s position for her eldest son and an indenture for Clarence. It is unclear how much Mrs Ray paid, but he completed his indenture and achieved his Second Mate’s Certificate just five years later. However, that’s as far as his career at sea took him. By the time of the 1911 census, he was married with three children and working as a farmer not far from Hastings.

A Day in the Life

Unfortunately, few contemporary accounts of life on board Cutty Sark survive. However, logbooks, Crew Lists, letters and memoirs combine to help us piece together a typical ‘day in the life’, if there could be such a thing. On the ship’s final voyage, the letters of Clarence Ray, the apprentice, sent to his mother between June and December 1894, paint a fascinating and invaluable picture of all aspects of his experience, as depicted in the following sections.

Watch System

We start work at 5.30 in the morning but that is every other morning of course because the other watch will be on deck from 4 to 8 the next morning, the dog watches from 4 to 6 and 6 till 8 at night, are so that we should not get the same watch on deck at the same time, we knock off work at 4 one day and 6 the next in our watch on deck at night we have to keep time and ring bells.

The crew were split into a starboard and a port watch. If ‘all hands’ were called on deck, they would take their positions on the relevant sides of the ship. The day and night was split into five main watches of four hours each and two shorter ‘dog watches’ of two hours. The dog watches ensured that the sailors changed which watch they stood from day to day. The ship’s bell, at the anchor deck, marked the passing of time and the start of a new watch.

Accommodation

We have a jolly lot of fellows in the ‘house’, there are six of us altogether, we are divided into two watches Wilcox, Tyrrer and Nibo (the scipper’s son) are in the Port and Webb Shuttleworth & I are in Starboard Watch.

After 1872, there were two wood-panelled deckhouses on the main deck as accommodation for the crew. The fore deckhouse – for the ordinary and able seamen – had 12 bunks. The apprentices and petty officers, of the aft deckhouse, were rewarded for their superiority of rank with ten bunks of a slightly larger size. According to the original profile and plan of John Rennie (draughtsman of Cutty Sark), a partition would have separated the apprentices from the petty officers so that the cook and carpenter had their own space. This may explain why they are not mentioned in Ray’s account, though, of course, it could also be down to 16-year-old Ray focusing on his contemporaries rather than his superiors. ‘Nibo (the scipper’s son) [sic]’ was Albert Sydney Woodget, youngest son of Master Richard Woodget. Like his brothers and Ray, Albert Sydney had begun his indenture aboard Cutty Sark.

Ray goes on to say: ‘Wilcox and Webb have served their time in the Sark but are coming this voyage to get their 2nd mates certificate.’ As third mate, Wilcox had made the normal progression from apprentice. Indeed, Wilcox received his discharge from the voyage on 26 March 1895 and received his Second Mate’s Certificate less than one month later.

Daily Tasks

Our first job at 5.30 in the morning is to wash the pigs and closets out. I always heard that pigs were unclean animals but now I know it for a positive fact.

Cutty Sark had a pigpen beneath the anchor deck and a chicken coop beneath the poop deck. Both were accounted for in the ship’s specification: ‘Four hen coops of Teak 8ft long. Pig houses covered with teak … placed where required.’ They were intended to supplement the diet of the crew, but washing the pigs was clearly an unpopular duty.

I chip, repair, paint and generally do up! ... I have to do my share of work on deck and aloft and a jolly lot more too ... which is generally overhauling and stopping buntlines, clew lines and leech lines and making the stay sails fast which is the worst of all especially if she is rolling at all.

The two main watches of the day were used to chip, repair and paint. Sail repair work and cordage were also key responsibilities. Not only was it essential for the crew to ensure that their vessel was always prepared for whatever the weather could throw at them, keeping on top of the maintenance also helped to ensure that a ship would retain its classification when surveyed.

Ah it is a hard life but you need not think I do not like it for I am enjoying myself very much … Last week I had to go to the wheel and learn to steer.

It is thought that little maintenance work was likely to have taken place during the dog watches. Instead, this time was used for training. Apprentices were providing their service for free in exchange for ‘learning the ropes’. Lessons in steering and navigation would be invaluable for their future career.

Discipline and Punishment

If we go to sleep in our watch on deck they make us ride the grey mare that is sit up on the upper topsail yard for the rest of the watch.

Master Woodget is also said to have dropped a nest of baby rats onto the face of an apprentice who had overslept. Discipline over a ship was unique to the man in charge. The risk of punishment was essential to ensure duties were fulfilled. But a draconian approach, such as that employed by Master William Bruce on the ‘Hell-Ship Voyage’, ran the risk of alienating a crew. Of course, a particularly effective method of punishment was to withhold pay. The Board of Trade provided guidelines as to the amount of pay that should be denied, depending upon the severity of the charge.

The Quirks of Master Richard Woodget

The old man has got 3 dogs, scotch collies, and when we go down in the cabin to see the time they go for us which makes it rather thick.

As we have seen, Richard Woodget was a remarkable character. It is perhaps a mark of the esteem with which Woodget was regarded by his crew that in one of his photographs of Cutty Sark he had been rowed out on the captain’s gig by an apprentice to set up his extensive equipment in order to take a port-side photograph of the famous ship, under sail. This would have meant leaving his crew to their own devices, something many a master would not have been willing to risk. Cutty Sark’s specification provided that a ‘time-piece’ be hung in the saloon of the Liverpool House. It was perhaps the fact that these animals were also kept in the salubrious settings of the saloon that proved unpopular, as, according to Ray, they went for any men who came in to check the time.

Food

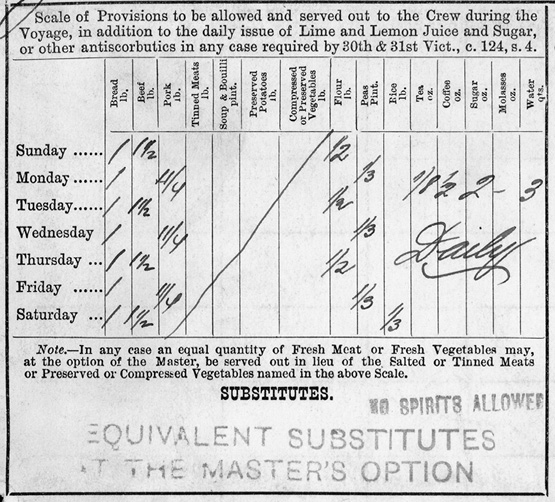

We get coffee at 5 o’clock every other morning coffee for breakfast and tea for tea. Monday, Wednesday, Friday pea soup and pork; Tuesday and Thursday Salt Tram Horse and bread; Saturday Junk and Spuds; Sunday Leu Pie. Sugar and butter we get 14 ozs every week. We get a pannikin of lime juice every day at 12 o’clock. Leu pie is my favourite dinner it is cooked altogether in a great kid, fresh meat and spuds all in a soup like, underneath and dough on top. Oh Lor, I could eat 3 whacks of it now, of course we get any amount of dog biscuit.

What food the crew could expect to eat had been set out in the Agreement & Account of Crew. Each member was expected to sign or mark the Crew List in acknowledgement.

Agreement and account of crew list, front page 63557, foreign going ship. National Maritime Museum, London (F5135)

The food on board had to remain edible for the whole voyage as there would be scant opportunity to pick up fresh supplies. Dried vegetables dominated the menu, along with salted meat kept in harness casks of salted water. Preserved in this way, the meat could last up to four months, though it would gradually turn an unappetising green. Hard tack, or ship’s biscuits, were long-lasting but tasteless crackers that were so hard they were capable of breaking teeth. Commonly, they were broken down and added to a stew for extra carbohydrates. Before the biscuits could be eaten, weevils (small beetles) would have to be shaken from them. A daily allocation of tea and water as well as flour for bread was also provided. Much was dependent upon the inventiveness of the cook to come up with something enticing. It is perhaps unsurprising that in a list of supplies that were picked up by Cutty Sark in 1882 from Madras (Chennai), two bottles of curry powder were included.

Fresh water was stored below deck in ten 400-gallon tanks. These were connected to a fresh-water pump on the main deck. Each member of the crew was entitled to six pints (just under 3.5 litres) of fresh water a day, but as this was also necessary for cooking the food, much of this water would go to the cook. A salt-water pump was used for washing and for flushing the toilets, or ‘heads’, which were located at the bow of the ship and did not have a flushing system, so were cleared by the same salt water.

Post

In another letter, Ray signed off:

‘Don’t forget to write to me. The address will be:

CE Ray

℅ Captain Woodget

SS Cutty Sark

Brisbane

Woodget is spelt get not gate.

Your loving son,

CE Ray’

Special mail ships delivered mail all over the world. The first transatlantic contract was given to the Cunard Line. When the crew knew where they were headed to, as in Ray’s case, it was relatively easy to provide an address. Ray also wrote: ‘the day I wrote a letter for the Pilot … I had to scribble whatever first came into my head.’ It seems from this that pilots were willing to take the crew’s letters with them once they were ready to depart a ship.

Crew Origin, Deserters and Stowaways

Cutty Sark’s crew came from all over the world. It was not until the First World War and the introduction of the Defence of the Realm Act that carrying a passport became imperative for crossing borders. Before that, freedom of movement was relatively unimpeded.

The majority of the crew were from London and the South East, but a large number came from the Scandinavian nations, Germany and the Netherlands. Ten men came from the West Indies, four from Australia, 24 from North America and Canada and two from Chile. Perhaps surprisingly for the period, two Frenchmen also served as able seamen.

A total of 681 names were entered on Crew Lists, of whom 28 then failed to join the ship for whatever reason. That leaves 653 people who actually served on board Cutty Sark. Of these, 95 (or 14.5 per cent) deserted and 82 (or 12 per cent) could not sign their own name. Desertions became much more frequent once Cutty Sark began to voyage to Australia. If a man was intent on desertion, the common language and relative ease of avoiding recapture or recrimination made Australia an attractive option. What was more attractive was that wages were higher and the cost of living cheaper in Australia. Thus a pattern emerged of crew being taken on in London, on London wages, and then deserting in Australia, with the result that new crew had to be taken on there to replace them, on higher Australian wages.

Just two men were recorded as stowaways on Cutty Sark during her British career. Both found their way onto the ship in Shanghai. Henry King was discovered on 26 June 1870, one day after the ship had set out for London from Shanghai. According to the logbook, he claimed he was willing to work but, from 18 August, he was reported as ‘idle’. John Doile was found an impressive seven days after the ship had left Shanghai in July 1873. He is listed in the Crew List as an able seaman and as being of good character, but is not mentioned again.