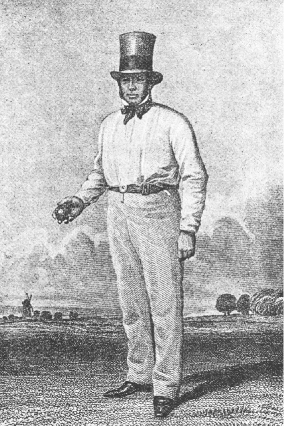

At the risk of turning this book into a history of millinery, our fourteenth object is also a hat. This hat is tall, black and fashionable, as worn by William Clarke’s All-England XI when they toured the country in the late 1840s.

Few people had as much impact on nineteenth-century cricket as William Clarke. Such was his influence that in Harry Altham’s 1926 book, A History of Cricket, the author bracketed Clarke alongside William Lillywhite and W.G. Grace when it came to cricket ‘immortality’.

So who was William Clarke? When William Denison published his Sketches of Players in 1846 he shed some light on the man. Born in Nottingham on 24 December 1798, he was 5 feet 9 inches and a touch under 14 stone. His sturdy proportions might have had something to do with the fact he was a ‘licensed victualler’. Denison continued: ‘He kept the celebrated Trent Bridge Cricket Ground, about a mile out of the town of Nottingham, and has long been known in the matches played in all the Northern and Midland districts of England, as a cricketer of no mean capabilities.’ Underarm bowling was Clarke’s forte, and Denison noted that in the 1845 season he had taken 106 wickets in twelve matches, ‘producing an average of 8¾ per match’.

Denison’s book was published in the same year, 1846, that Clarke found the team where he would make his name and warrant his place among cricket’s immortals. The seeds of the side had been sown the previous year when Clarke staged a match at the Trent Bridge ground he managed between his Nottinghamshire XI and a team billed as ‘England’. The game was a commercial triumph, and Clarke saw an opportunity not only to popularise cricket throughout England, but also to make himself rich. He moved to London, wheedled his way into the capital’s cricket community – even bowling to MCC members – and fine-tuned his plan for a touring team of professional players. Clarke called it the Eleven of England, but it soon came to be known as the All-England XI. ‘There had, of course, been England sides before,’ explained Altham. ‘But they had been elevens selected either by the MCC or by private backers… never before had anyone thought of organising and maintaining in the field for a series of matches, and over a period of years, a side that represented the very cream of English cricket.’

Clarke was a man of sturdy proportions, a ‘licensed victualler’

The idea took a while to gather momentum. Their first match was in August 1846, a five-wicket defeat against Twenty of Sheffield. It was another year until their next match, but then the All-England XI began to capture the public imagination, owing in no small part to Clarke’s promotional strategy. Asked by James Dark, proprietor of Lord’s at the time, why he was taking his team to Newcastle instead of playing all his matches in the south of England, Clarke replied: ‘I shall play sides strong or weak, with numbers or with bowlers given, and I shall play all over the country too – mark my words – and it will make good for cricket.’

The All-England XI did indeed ‘make good for cricket’. Clarke assembled the best players in the English game, described by John Major as ‘the forerunners of Kerry Packer’s cricket circus one and a quarter centuries later’ (see chapter 62). Among the players were: Alfred Mynn, nicknamed ‘The Lion of Kent’ and the Ian Botham of his day; Nicholas Felix, a brilliant left-handed batsman and the man credited with inventing batting gloves; an ageing William Lillywhite, signed up more for his reputation than his prowess; and John Wisden, the best all-rounder of his day and the man who founded the eponymous cricket almanack. The players dressed like the stars that they were, in white shirts with red stripes, black boots and tall fashionable hats.

Between 1846 and 1849 Clarke’s All-England XI toured the country, winning twenty-seven of its fifty-one matches and losing just eleven. As their fame spread so their fixture list became ever more crowded – by 1851 they were playing thirty-four matches in the season, and the demands on the players were becoming intolerable. In an age when the stagecoach was still the standard mode of transport for long distances, the travelling was prodigious. ‘Often the eleven would travel down from the North all through the night to play in one of the big fixtures in London, or find themselves condemned to a five or six hours’ coach drive in the dark through the muddy lanes of Devonshire and Cornwall, or over the bleak flats of Lincolnshire,’ wrote Altham.

The stagecoach was still the standard mode of transport travelling was prodigious

In return the players were paid between three and five guineas a match, not much considering they were the best in the land. They asked for more, but Clarke wouldn’t budge; he even took a cut from any sponsorship deal a player might land. Yet he was becoming a very rich man, acculmulating wealth from the thousands of cricket fans who paid to watch their heroes at grounds up and down the country.

Eventually the players revolted, led by John Wisden, who in 1852 established the United All-England XI to rival Clarke’s side. Most of the players Wisden recruited were those who had narrowly missed out on selection for the All-England XI – good enough, in other words, to pose a serious threat to the hegemony of Clarke.

Nonetheless, Clarke’s XI continued to tour. In 1854 they were in Bristol, and a five-year-old boy was taken by his father to watch them. All he remembered in his later years was that the players ‘wore top hats’. The boy’s name was William Gilbert Grace.

Clarke died two years later, two months after he had played his last game for the All-England XI against Whitehaven. Yet he had set in train an idea that continued for thirty more years until the emergence of an official England Test XI finally made the all-star teams redundant.

‘They were truly missionaries of cricket,’ wrote Harry Altham, ‘winning to knowledge and appreciation of the game whole districts where hitherto it had been primitive and undeveloped.’