England against Australia. The Ashes. Just the mention of the word gets the spine tingling. Yet it might have been so different had the subject of our next object, captured in this photograph, taken to cricket. Evidence exists that the United States of America were playing cricket decades before anyone in Australia picked up a bat with a New York XI beating a side from London as early as 1751.

Nearly a century later, in 1844, the United States met Canada in New York in what is generally accepted to be the first ever international cricket match. Canada batted first and were all out for 82, 18 more than the Americans made as David Winkworth and Freddy French ripped through the home side’s batting order.

An estimated 15,000 spectators watched the match, and the following year the USA travelled to Canada for the rematch.

In 1859 George Parr, who four years later would lead the second England touring party to Australia, skippered a side on a tour of Canada and the USA. The tour was three years in the planning, money being the primary issue at stake. Eventually the Montreal Club guaranteed to pay the twelve players £50 each plus all expenses.

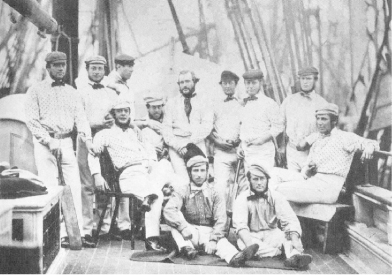

The party sailed out on the SS Nova Scotian, posing for a photo on deck which we’ve chosen as our seventeenth object. It wasn’t a particularly agreeable crossing; rough weather confined most of the squad to their quarters, but their mood was soon brightened upon landing in Canada. ‘The opening match at Montreal was well patronised,’ wrote Harry Altham in A History of Cricket, ‘especially by the fair sex.’

USA was playing cricket decades before anyone in Australia

The tourists were too strong for the home side, winning by eight wickets and, after a royal feast in the prestigious St Lawrence Hotel, they departed for New York. Two thousand people were waiting for the tourists when they arrived, and a further 23,000 came to the game to see England crush New York by an innings and 64 runs.

The excitement continued in Philadelphia, where a thousand young women looked on daintily from the ladies’ stand as the tourists won by seven wickets.

Parr’s side won their remaining two matches and reached Liverpool on 11 November after what everyone agreed was a successful tour. As well as winning all their matches and becoming acquainted with many wholesome young ladies, the players pocketed nearly £100 each from their two-month trip.

Cricket had clearly taken root in the United States, and more than a few of the tourists expected to return in the near future on a second tour. But within eighteen months of the tour, the USA descended into civil war. Instead, as we’ve just seen, England’s cricketers took up offers to tour Australia.

Peace returned to the States in 1865, but cricket never again enjoyed the levels of popularity that it had pre-war. John Major has suggested that ‘it was perhaps too leisurely a sport for such a young and thrusting nation’. But if this were true, why did cricket find such success in Australia, even younger and arguably more thrusting than America?

The truth is that more and more immigrants came to America in the second half of the nineteenth century. What self-respecting Irish, German or Italian would want to play cricket, a sport seen as representative of the British Empire? Instead they played baseball, and where cricket did survive in the States – notably in Philadelphia (the club was founded in 1854) – it was played by men of British descent. But even here cricket gradually died out, and in 1924 the Philadelphian club disbanded its cricket team.

Nearly three-quarters of a century later, the club was resurrected by the Philadelphia Sporting Club’s director of tennis – a New Zealander!