Hanif Mohammad was born and brought up in Junagadh, north of Bombay. That’s where, with his four brothers, he first played cricket, until in 1947 the family left India for the newly founded nation of Pakistan.

The Mohammads set up home in a disused Hindu temple in Karachi, and the boys continued to play cricket (four of them would be capped by Pakistan). ‘A small, low wall separated the garden from the road on the legside,’ Hanif recalled later. ‘If we lifted the tennis ball over it we were out. We seldom did. That was our secret.’

Five years after the formation of Pakistan Hanif was playing cricket for them aged just seventeen. Two years earlier he’d announced himself to the world as a ‘Boy Wonder’, scoring a century for Karachi Muslims against Punjab.

Now, on his Test debut for Pakistan, he again showed his class, scoring 51 out of a total of 150. The ‘Boy Wonder’ had graduated to the ‘Little Master’, and for the next two decades Hanif Mohammad broke cricket records at will. No other cricketer had ever shown such concentration as Hanif did match after match, and because of it he did more than anyone to establish Pakistan as a force in international cricket.

In 1954 Pakistan made their first tour to England led by Abdul Hafeez, who eight years earlier had been a member of the Indian party skippered by the Nawab of Pataudi (see chapter 45). The Indians had failed to win any Tests; but Pakistan won their fourth match of the series, beating England by 24 runs at the Oval, the only side to win a Test match on a first visit to England. In its account of the tour Wisden described Hanif as ‘by far the best batsman in the party. At first almost purely defensive, he later blossomed into a most attractive opening batsman, bringing off delightful all-round strokes with a power his slight build belied.’

Hanif continued to plunder runs against the best in the world, racking up centuries against India, New Zealand and the West Indies. But it was what happened at Bridgetown, Barbados, against the West Indies in January 1958 that elevated Hanif to a higher plane.

West Indies batted first and made a daunting 579. Then they skittled out Pakistan for 106 with paceman Roy Gilchrist taking four for 32. Pakistan went out to bat again requiring 473 to avoid an innings defeat. The helmetless Hanif, all 5 feet 4 inches of him, ducked under a bouncer for his very first ball, and then turned to watch as the ball kept on rising and rising, over the head of the wicketkeeper and into the sightscreen. For a Pakistani batsman, playing in his country’s first Test against the West Indies, it was a knee-trembling introduction to Caribbean cricket.

Hanif saw off Gilchrist, and then the fast-medium swing bowling of Denis Atkinson. Each hour he called for a drink, wrung out his neckerchief, and refocused his mind. Colin Smith came on with his off-breaks but failed to dislodge Hanif. Nor did the left-arm spin of Alf Valentine, nor even the trickery of Garry Sobers.

At the end of the day Hanif had reached an unbeaten 161, but Pakistan were still 200 shy of the West Indies’ total with two days to play. That night teammate Abdul Kardar, who had played for India under the name Abdul Hafeez, pushed a note under the door of Hanif’s hotel room: ‘Little One,’ ran the note. ‘You can still save us. Understand that they just cannot get you out. It is them that are becoming desperate now.’

The next day Gilchrist tried again to dislodge Hanif, but again he wouldn’t budge. By now the sun had burned three layers of skin from his face, but his mind remained intact. The penultimate day ended with Pakistan 525 for three (a lead of 52) with Hanif still there on 270. He was finally out the next day for 337, second only to Len Hutton’s 364 in the annals of Test-match batting. The sixteen hours and thirty-nine minutes that he batted was a new record – one that will probably never be broken.

But that wasn’t what mattered to Hanif. The match had been saved, and Pakistan had shown once again that they were a match for any team in Test cricket.

A year later Hanif set another record, batting for Karachi against Bahawalpur, when he was run out for 499 while attempting to reach the magical 500. This feat would stand until Brian Lara’s 501 for Warwickshire against Durham in 1994.

Each hour he called for a drink, wrung out his handkerchief, and refocused his mind

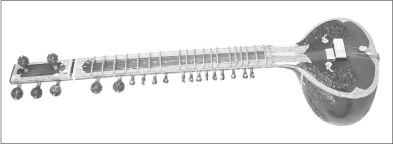

The last of Hanif’s magnificently obdurate innings was at Lord’s in 1967. Remembering it, the Independent wrote in 1992 that Hanif ‘clung to the crease like a leech until he ran out of partners at 3.24pm on the Monday’. But once more he had done enough to save Pakistan, his unbeaten 187 dragging his side from 99 for six to the safety of 354. It hadn’t been pretty; in fact it had been characteristically dour, with Hanif taking nine hours and 556 balls to compile his runs. Yet Pakistan’s honour was intact and Hanif could rest easy that night. ‘Indifferent to the ensuing trickle of adulation as he was to the torrent of criticism,’ commented the Independent, ‘the reluctant entertainer returned to his hotel room and lost himself in a soothing recording of his beloved sitar music.’