Anyone who knows anything about skiffle will tell you that its genesis occurred on 13 July 1954, when Lonnie Donegan recorded ‘Rock Island Line’, Lead Belly’s song about the wily train driver who fools the operator of a big tollgate just outside of New Orleans. Except the Rock Island Line doesn’t go to New Orleans and there never were any tollgates on American railroads. And Lead Belly didn’t write that song. So what is really going on here?

To get to the bottom of the story, we have to go back almost exactly one hundred years before that historic recording, to 10 July 1854, when the Chicago & Rock Island Railroad was officially opened. For two years, work gangs had been laying steel rails forged in England along a 181-mile route due west across Illinois from the city of Chicago to Rock Island on the banks of the Mississippi. The plan was to cross the mighty river and bring the iron road to the American west.

For the men who owned the railroads, the Mississippi presented a formidable physical barrier, still half a mile wide at Rock Island, a thousand miles upstream from the Gulf of Mexico. Beyond it, the western plains were beginning to be settled and, in 1846, the land across the river from Illinois became the state of Iowa. Riverboats had a monopoly on transport across and along the Mississippi, but the intentions of the owners of the Chicago & Rock Island Railroad became clear in 1851 when they asked the Iowa legislature to grant them land to build a depot in Davenport, directly across the river from Rock Island.

Based on a topographical survey conducted in 1837 by Lt Robert E. Lee, engineers had chosen a prime spot to build the first bridge across Big Muddy and construction began in July 1853. The largest island in the whole of the Mississippi, Rock Island offered a sturdy jumping-off point for the 1,528-foot wooden bridge, which was supported by six granite piers. The first train crossed over to the Iowa shore on 21 April 1856, linking up with the Mississippi & Missouri Railroad, which was making heavy going of building a track across Iowa towards Council Bluffs on the eastern bank of the Missouri River. Several other railroads had reached the Mississippi, but none had managed to cross it. The Chicago & Rock Island Railroad had brought the possibility of transcontinental trade a step closer.

Before the coming of the railroad, rivers provided the main form of transport in the American interior, with a network of canals connecting tributaries and lakes, ferrying goods and people inland from the coast. But this distribution network was subject to seasonal changes: rivers in the north would freeze in the winter; some in the south would run dry in the summer. Many were prone to flooding. The railroad offered an all-weather form of transport and, since 1830, tracks had been laid linking eastern cities to the Atlantic coast.

Their livelihoods threatened by the railroad, the riverboat owners opposed the bridge from the outset, arguing that it would cause an impediment to navigation. Informing their complaints was a struggle over trade routes across the US. The southern states had built their distribution networks on a north–south axis using riverine routes. In the north, the east-to-west expansion of the railroad threatened southern interests. Most vocal among those opposing the bridge was US Secretary for War Jefferson Davis, who would go on to lead the Confederacy during the Civil War. As the issue of slavery became increasingly divisive, southern legislators, fearful of being dominated by the more populous north, sought to ensure that any new states joining the union would be pro-slavery. Davis used his office to promote a southern transcontinental route for the railroads in the hope that the west would be settled by slave-owning southerners. When the notion of a river crossing in the upper Mississippi presented a threat to his plans, he took legal action to stop the Chicago & Rock Island Railroad from building their bridge.

He was ultimately unsuccessful, but other interests were more determined. Just two weeks after the bridge was opened, on the night of 6 May 1857, the steamboat Effie Afton had passed beneath the open draw of the bridge when she suddenly veered to the right. Her starboard engine stopped, power appeared to increase in the port engine and she hit the pier next to the open draw. A stove in one of the cabins was overturned and soon the entire boat was aflame, with fire spreading to the wooden superstructure of the bridge, destroying one of the spans. Immediately suspicion fell on the riverboat owners. What was the Effie Afton doing so far north from her usual route between Louisville and New Orleans? Why was she out on the river long after other boats had tied up? How did she burn so quickly? And was she drifting helplessly or deliberately driven into the pier?

When it took just four months to repair the bridge, the riverboat owners resorted to the courts, demanding damages for the loss of the Effie Afton and seeking to prove that the bridge was a hazard. The Chicago & Rock Island company hired an experienced Illinois railroad lawyer to be their lead counsel. Abraham Lincoln had handled a number of cases concerning rights of navigation around railroad bridges on other rivers, some of which had gone all the way to the Supreme Court.

The judge dismissed the case after a trial that lasted fourteen days and resulted in a hung jury. Seen as a moral victory for the railroad, the Rock Island Bridge case drew national attention, helping to establish Lincoln’s reputation ahead of his bid for the presidency in 1860.

The riverboat owners kept up their legal opposition for another decade, finally conceding defeat in December 1867. By that time there were several other bridges across the Mississippi and a transcontinental railway was being constructed between Sacramento, California, and Council Bluffs. The Mississippi and Missouri Railroad, in its attempt to cross Iowa ahead of competing railroads, had hit financial difficulties and was absorbed by the Chicago & Rock Island Railroad, whose track-laying gangs finally reached Council Bluffs on 10 May 1869.

This event was overshadowed by news that, just the day before, the final spike had been driven on the transcontinental railway at Promontory Point in Utah, uniting the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads. Where once wagon trains had taken six weeks to cross from coast to coast, the steam trains had now cut the journey to just six days.

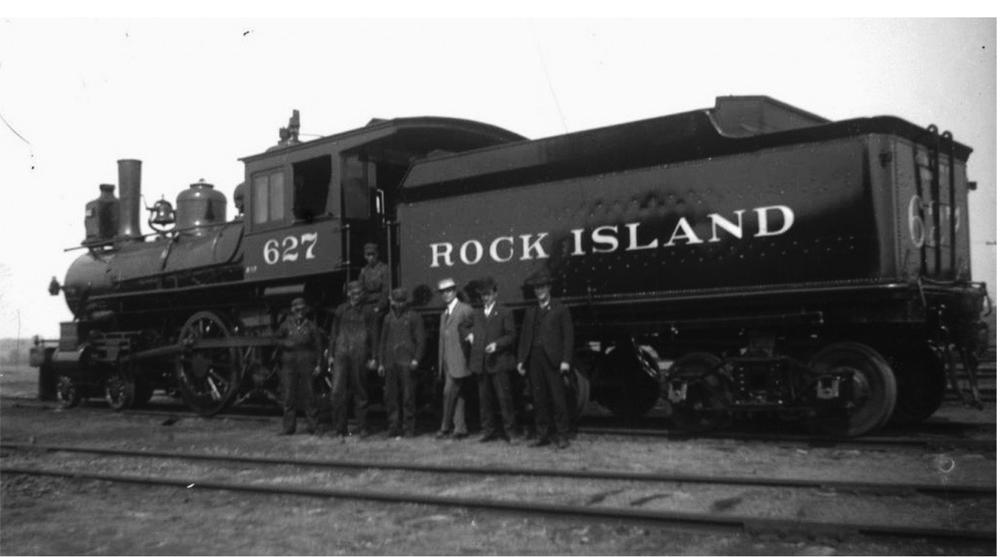

Ride it like you’re flying: a Rock Island locomotive, c.1880

In the railroad boom years that followed, the company, changing its name to the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad, began building lines that radiated out from the Rock Island crossing: north to Minneapolis, west to Denver and south across the Missouri River into Kansas. In 1882, a song appeared extolling the virtues of the network, written by one J. A. Roff:*

Now listen to the jingle,

The rumble and the roar

As she dashes through the woodland

And speeds along the shore;

See the mighty rushing engine,

Hear her merry bell ring out

As they speed along in safety

On the Great Rock Island Route.

Shortly after the song was published, the track gangs reached Herington, Kansas, where the line split, one branch heading southwest towards New Mexico while the other dived due south towards Oklahoma. This southern spur followed the Chisholm Trail, used by cattle herders to bring their stock to railheads in Kansas and Missouri. Crossing Oklahoma, the tracks reached the Texas border in late 1892. By the end of the century, the Rock Island Railroad operated 3,568 miles of track, all of it west of Chicago, and had an annual turnover of $20 million.

In the early years of the new century, the company pushed south across Texas, heading for the Gulf port of Galveston. In 1904, it purchased the Choctaw, Oklahoma and Gulf Railroad, allowing it to link Memphis, Little Rock and Oklahoma City with Tucumcari, New Mexico, from where passengers could transfer to Southern Pacific trains serving California. In the same year, the Rock Island Employees Club was founded at the company’s headquarters in Chicago and, within a decade, had expanded to involve all levels of workers across the network, from brakemen and porters to engineers working in train yards. With separate organisations for black and white employees, the clubs staged social events such as picnics and sporting competitions between various depots.

In 1920, the company was actively encouraging employees to ‘boost’ the Rock Island brand. Music was at the forefront of this effort, with choirs and singing groups sent to perform at public gatherings, their members encouraged to write material that promoted the railroad. One of these booster groups, the Rock Island Colored Quartet, was formed by workers from the company’s central freight yard and repair shops at Biddle,† just outside Little Rock, Arkansas. In January 1930, the Rock Island Magazine reported that a member of the Quartet, engine wiper Clarence Wilson, had composed a booster song entitled ‘Buy Your Ticket Over Rock Island Lines’, which was being performed in the Little Rock area. The verses spoke of the different characters that worked out of the Biddle depot, while the chorus extolled the virtues of the railroad:

Rock Island Line is a mighty good road

Passengers get on board if you want to ride

Ride it like you’re flying

Be sure you buy your ticket

Over the Rock Island Line

In the north-west of the state, straddling the Texas–Louisiana border, lies Caddo Lake. At the end of the nineteenth century, the area was home to rural communities of African Americans who made up 65 per cent of the local population. It was in this secluded area, near the town of Mooringsport, that Huddie Ledbetter was born in January 1888. From an early age he showed an aptitude for singing and playing guitar, making a name for himself as a ‘musicianer’ by performing at social gatherings. He also gained a reputation as someone who would never back down from a fight. In the early years of the twentieth century, Caddo Lake still had the aura of a frontier town, where men were expected to resolve their differences without recourse to the law. By the age of sixteen, Huddie carried a pistol as well as a guitar to local dances.

In 1910, he travelled to Dallas, where he teamed up with a teenage blues singer named Blind Lemon Jefferson. In the following decade, Jefferson would rise to fame as the first country blues artist, but during their time together, he and Huddie were just a couple of musicianers earning whatever they could by playing wherever they happened to be. A tall, well-built man with a strong singing voice, Huddie needed a powerful instrument to put his songs across, and during his time in Dallas he acquired the twelve-string guitar that was to become his trademark.

In 1915, Huddie was settled with his wife of seven years, Lethe Henderson, in Marshall, Texas, just across the state line from Mooringsport. Their lives were shattered when Huddie was involved in an altercation that resulted in him being convicted of carrying a pistol and sentenced to thirty days on the chain gang. Unable to countenance the treatment meted out to him, he escaped after just three days, heading eighty-five miles north to live with members of his extended family in De Kalb, Texas. There he worked as a cotton picker under the assumed name of William Boyd. While walking to a dance with a group of friends in December 1917, Huddie, never the most faithful of husbands, became involved in an argument with one of his companions, Will Stafford, over the affections of a young woman. The dispute quickly escalated, violence ensued and Huddie pulled out his pistol and shot Stafford down. Convicted of murder, Huddie was sentenced to serve seven to thirty years and soon found himself Sugarland bound.

The Central State Prison Farm, just west of Houston, took its familiar name from nearby Sugar Land, a company town built by the Imperial Sugar Company in the first decade of the twentieth century to process sugar cane from the surrounding fields. A humid, subtropical climate made labouring in the fields a challenge, but Huddie rose to become a team leader of a work gang. Realising that he would be at Sugarland for a long time, he used his talent as a performer to win a small degree of liberty within the prison regime. On Sundays, he was allowed to travel unaccompanied to other camps within the prison to entertain inmates with his songs and stories.

It was during this time that he picked up the nickname by which he would come to be known around the world: Lead Belly. Many of the songs that he later popularised came from his time in Sugarland. Most famous of them all was ‘Midnight Special’, which took its name from a Southern Pacific train that left Houston every night around 11 p.m., heading west for San Antonio. Its lights would sometimes flicker on the walls of inmates’ cells as the train passed the prison, giving rise to the belief that if the light from the Midnight Special fell on you, you would be next for parole.

In January 1924, Texas Governor Pat Neff visited the prison and Lead Belly was called upon to provide some evening entertainment. Desperate for his freedom, Lead Belly composed a song asking to be pardoned for his crime, singing, ‘If I had you Governor Neff like you got me, I’d wake up in the morning and set you free.’ Although he impressed the governor with his ability to write songs, Lead Belly had to wait a whole year before he got his pardon, signed by Neff on his last day in office. During his time as governor, Neff signed very few pardons, and the fact that he made an exception for Lead Belly is probably a sign of his generosity towards the convict musicianer – although any suggestion of excessive clemency is tempered by the fact that Lead Belly would have been eligible for parole just four months later, having served the minimum seven years demanded by his sentence.

Lead Belly headed back to Mooringsport, where the discovery of oil had created an economic boom. He worked as a roustabout, performing at night in local barrelhouses. He again found himself in trouble with the law in January 1930, when he was arrested following an altercation with a group of white men. According to the press report of his trial, the trouble began when Lead Belly came upon the local Salvation Army band playing on a street corner one Saturday night. When he began to dance in time to their music, some white bystanders took exception, presumably thinking he was being disrespectful. When they told him to move along, he did so, but carried on dancing, provoking a group of men to go after him. When knives were pulled, Lead Belly drew his in self-defence and, in the scuffle that followed, he received a gash to the top of his head, while one of his attackers, Dick Ellet, had his arm slashed.

When word spread that a ‘drunk crazed negro’ had attempted to murder a white man, an angry mob descended on the parish jail where Lead Belly was being held. Only the swift action of the law enforcement officers guarding the jailhouse saved him from being lynched. Knife fights had always been a part of Lead Belly’s life. His body bore the scars of many barrelhouse brawls. He’d often go and report what had happened to the local sheriff’s office, only to be told to stay out of town for a while. But this was different. Unlike his other victims, Dick Ellet was white and, as a result, Lead Belly would have to face the full force of the law. Convicted of attempted murder in a trial lasting just a day, he was sentenced to serve six to ten years’ hard labour.

At the age of forty-three, Lead Belly found himself in one of the most notorious prisons in the whole of the US – Angola State Penitentiary. Here, the regime made Sugarland seem easy by comparison. Slavery may have been abolished at the end of the Civil War, but sixty-five years later, its practices were still being employed at Angola. Shackled together with chains, working in the fields from dawn to dusk in sweltering heat and humidity, at night inmates slept on the floor of dormitories that held seven hundred men, where the lights were never switched off. Surrounded on three sides by the Mississippi River and the tangled forest of the Tunica Hills in the east, there was very little opportunity for escape.

As in Sugarland, Lead Belly soon gained a reputation as a talented performer whose skill on the twelve-string guitar drew the attention of prisoners and guards alike. When song collectors from the Library of Congress arrived at the prison in July 1933, looking to record vernacular material, Lead Belly was an obvious candidate for their project.

John Lomax was a sixty-six-year-old college professor and folklorist researching African American work songs for the Archives of Folk Music at the Library of Congress. Equipped with the latest portable recording technology and assisted by his eighteen-year-old son Alan, Lomax toured labour camps across the south in search of material. His focus soon turned to prisons, where incarceration isolated singers from the popular music of the day. At Angola Lead Belly impressed the Lomaxes with the breadth of his repertoire and his storytelling skills. Among the seven songs he recorded that day was the one that would become his signature tune: ‘Goodnight Irene’.

Believing that it had been his songwriting that got him out of Sugarland, Lead Belly resolved to try the same method to secure his release from Angola. When the Lomaxes returned to the prison in June 1934, Lead Belly recorded a song asking Louisiana Governor O. K. Allen for a pardon, which he asked John Lomax to take to Baton Rouge and present to Governor Allen himself. Lomax duly delivered the recording and within a month – on 1 August 1934 – Lead Belly was set free.‡

He immediately wrote to John Lomax, offering to work as his ‘man’ – driving his car and carrying the heavy recording equipment. Lomax was in need of assistance. About to set off on another field recording expedition, his son Alan had been taken ill and was unable to accompany him. He hired Lead Belly and soon the pair were headed for Arkansas. Immediately Lomax realised what an asset he had. Rather than have to explain the nature of his project in patrician tones to often bemused and sometimes hostile prison staff, who in turn would order inmates to comply, he was able to send Lead Belly into the dormitories to tell the prisoners what was happening and to play them examples of the kind of songs Lomax was looking for.

In the first week of October 1934, at Cummins State Farm near Pine Bluff, a twenty-one-year-old convicted burglar named Kelly Pace came before Lomax’s recording machine, leading a group of seven fellow convicts. In close harmony, they sang ‘Rock Island Line’ in a call-and-response style. This wasn’t the first time Lomax had heard the song. It was among those he had collected at Tucker State Prison, some fifty miles north, just the week before. In the five years since it was written by Clarence Wilson in the Biddle Shops, ‘Buy Your Ticket on the Rock Island Line’ had been transformed from a booster tune into a song offering redemption from sin. In Lead Belly’s hands, that process would continue.

In many ways, Lead Belly was more of a song collector than John Lomax. While the learned professor needed to record performances in order to study them, Lead Belly could play a song after hearing it just a few times, appropriating material as he needed it. ‘Rock Island Line’ soon joined others in his song bag, although with just two verses it felt a little short. A talented improviser, Lead Belly had no compunction in extemporising a few extra verses, borrowing from children’s nursery rhymes and the blues tradition.

When their work in the prisons ended, Lomax invited Lead Belly to come north with him to appear at an academic event in Philadelphia organised by the Modern Language Association. He would be required not only to perform the songs but to give some context to their origins. Over the next few months, Lead Belly would accompany John and Alan Lomax to such august venues as Harvard University, where folklorists were bowled over by the depth of his repertoire and the power of his performances. For many of them, Lead Belly was the first vernacular singer they had seen, and his back story of plantation and prison offered them an insight into the daily lives of the rural African American community.

Lead Belly realised that the academics wanted to hear the stories behind his songs. Some, like those he had learned in childhood, were simple to explain. A song like ‘Rock Island Line’, however, had no background. Neither he nor Lomax had bothered to ask Kelly Pace where he had first heard the song, nor enquired whether it was used for work or pleasure. Recalling that the recording sessions at Cummings had been held next to the log pile, Lead Belly introduced ‘Rock Island Line’ as a chopping song. In June 1937, when he first recorded ‘Rock Island Line’, Lead Belly, singing a cappella, explained how a gang of men preparing a log would use the song to time the swing of their pole-axes.

When Alan Lomax arranged for the Golden Gate Quartet, a popular vocal group, to back Lead Belly on a recording of ‘Rock Island Line’ in June 1940, he dispensed with any spoken introduction, performing the song in its original call-and-response style. Lead Belly’s January 1942 recording for Moe Asch featured a whole new introduction concerning a train driver and a depot agent. It contains the list of livestock familiar from later versions, but fails to explain their significance. Things became clearer in October 1944, when Lead Belly, out in Hollywood hoping to make a career in movies, recorded the song for Columbia Records, backed by Paul Mason Howard on zither. He begins the introduction by telling us that the Rock Island train is out of ‘Mule-een’ – possibly a reference to Moline, the largest city in Rock Island County, Illinois. The depot agent throws a switch over the track to send the train ‘into the hole’.§ Instructed to pull into a siding, Lead Belly tells us, the train driver explains to the depot agent that he’s carrying cows, horses, hogs, sheep and goats. Due to animal welfare considerations, trains hauling livestock were given priority over ordinary freight and so the agent lets the train pass. As he picks up speed, the driver calls back, ‘I thank you, I thank you.’

Five months later in San Francisco, Lead Belly records the song again, starting his introduction with the wood-chopping story before segueing into the tale about the train. This time, however, the driver fools the depot agent, calling back that he’s carrying ‘all pig iron’ – possibly a livestock pun. The definitive version of ‘Rock Island Line’ is recorded in the summer of 1947 in New York City. Again, Lead Belly mentions that the train is coming back from ‘Mule-een’. Again, the depot agent tells the driver to take the train ‘into the hole’. Told that the train is hauling ‘all livestock’, the depot agent waves it past, only to be told, ‘I fooled you! I fooled you! I got all pig iron.’

It’s highly likely that it was on this performance that Lonnie Donegan based his version of ‘Rock Island Line’. Folkways released the 1947 recording in 1953, four years after Lead Belly’s death aged sixty-one. It was the title track of the second in a series of Huddie Ledbetter memorial albums. According to Chas McDevitt, this 10" thirteen-track record was a key source of inspiration for skiffle groups. Listening today, it’s easy to imagine that Donegan could have mistaken ‘Mule-een’ for ‘New Orleans’, given that Lead Belly himself hailed from Louisiana. Not so easy to imagine is where Donegan found the idea of the ‘big tollgate’. Lead Belly never mentions it, nor does he ever suggest in any of his recordings that a payment may have been due. In fact, there never were any tollgates on American railroads. Trains were charged to use tracks owned by other companies, but this was part of a contractual ‘trackage rights’ agreement, not a train-by-train cash fee.

However, by extemporising a story that made sense to his audience, Donegan was doing no more damage to the song than Lead Belly did when he introduced it to the staid New England academics at Harvard. Kelly Pace had also taken someone else’s song and shaped it into something that made sense in his environment. Who is to say that Clarence Wilson, the engine wiper at Biddle Shops, didn’t base his lyric on a popular tune of the day? Before commerce made ownership the key transactional interest of creativity, songs passed through culture by word of mouth and bore the fingerprints of everyone who ever sang them.

Little of this story was available to the young Englishmen who avidly collected American jazz and blues records in the 1930s. For them, a single recording was definitive, offering an insight into a culture that seemed to offer more excitement than the bland music they heard on BBC radio. Like members of an underground cult, they collated details of recording sessions, trying to discern the landscape of a musical form that they found so invigorating, yet so distant. Frustrated in their attempts to understand what it was that so moved them, some began to pick up instruments in the hope of emulating the primal sounds of New Orleans jazz.

* In 1904, William Kindt would publish a version of the song, with the same tune and slightly changed lyrics, under the title of ‘Wabash Cannonball’. Over time, and with many more lyrical changes, it would become one of the most famous songs in American folk music.

† Biddle Shops served the Rock Island’s Arkansas–Louisiana Division as a central repair works and roundhouse for the trains that ran west to Memphis, Tennessee, and south to where passengers could catch the Southern Pacific’s ‘Sunset Limited’ train that ran from New Orleans to Los Angeles at Eunice, Louisiana.

‡ There is no evidence that Allen ever heard the record. Lead Belly was not pardoned; rather, he gained his release under a programme that sought to cut the sentences of well-behaved prisoners to save state expenditure during the Great Depression.

§ During the Golden Age of the railroad, before the post-war development of the interstate highway system made car travel more attractive, freight trains had to give way to the more lucrative passenger services, pulling into a siding – going ‘in the hole’ in railroad slang – to wait while the express thundered past.