The first singles chart of 1956 that appeared in the New Musical Express confirmed the continuing dominance of Bill Haley and His Comets. ‘Rock Around the Clock’ had been in the Top Ten since mid-October, and now it was back at number one for the second time, having seen off a seasonal challenge from Dickie Valentine’s ‘Christmas Alphabet’. As the Brylcreemed British crooner plummeted down to number nine, Haley’s follow-up single, ‘Rock a-Beatin’ Boogie’, leapt from twenty-one to five, one place ahead of Alma Cogan’s saccharine-soppy Latin novelty number ‘Never Do a Tango with an Eskimo’ (if you do, you’ll end up with a freeze-up, according to its author, English songwriter Tommie Connor, who also penned ‘I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus’).

As the festive-themed songs began to come down with the Christmas decorations, dust-covered cowboys from way out west rode into the charts. ‘The Ballad of Davy Crockett’ by Bill Hayes entered at number thirteen, while ‘Sixteen Tons’ by Tennessee Ernie Ford debuted at eighteen. Galloping along with them was a third hombre, toting a guitar and singing about riding on the railroad: Lonnie Donegan appeared in the charts at number seventeen with ‘Rock Island Line’.

Two weeks later, he was in the Top Ten, telling the NME that, despite this sudden success, he had no intention of leaving his secure job in the rhythm section of the Chris Barber Jazz Band. If anything, he sounded rather embarrassed that Decca had released the song. ‘I don’t think it’s a particularly good recording,’ he said somewhat scornfully, before adding, ‘I even asked to have it withdrawn when I first heard it.’

Donegan clearly had yet to grasp what was happening to him. On the same page as his interview, Starpic Studios were offering super-glossy photos of the latest stars for just 1/6 each. Top of the list was Tony Curtis – ‘a thrilling new pose’. Straight in at number two – just above Hollywood starlet Shelley Winters – was Lonnie Donegan, ‘a great shot of the sensational singer of “Rock Island Line”’. Had any trad sideman ever been given the glossy Starpic treatment? Was Donegan even a jazz musician any more?

Decca seemed to think so. The word ‘Jazz’ appeared twice, either side of the hole, in his 10" 78 rpm hit single. Yet the record was credited to a skiffle band, while the song came from the repertoire of a blues singer. The B side was even older. ‘John Henry’ tells the story of a steel-driving man who labours on the railroads. In one of the greatest of all American folk songs, when a steam-driven hammer is brought in to replace him, he challenges it to a contest. John Henry cuts more rock than the machine, but dies from the effort.

So jazz, skiffle, blues or folk? What kind of music was this and how did it get into the pop charts? There simply weren’t enough fans of these relatively obscure styles to propel a single into the Top Ten. Some other forces must have been in play.

Was it the song itself that captured the imagination of the public? Having just been enchanted by the prospect of doing a tango with an Eskimo (or not, as the case may be), were record buyers taken by the notion of a thrilling ride on the Rock Island Line? Probably not. George Melly had recorded the song with barrelhouse piano accompaniment in 1951 but failed to catch the attention of record buyers.

The first chart of 1956 was full of highly polished pop. Most of the songs were string-drenched ballads and even the so-called hillbilly singers offered slick recordings backed by players who were masters of their craft. Bill Haley may have been the new sensation, but his records were crisp and clean. In such company, ‘Rock Island Line’ sounded raw. Lacking the metronomic time necessary for ballroom dancing, Lonnie Donegan’s Skiffle Group threw a spanner in the works of mum-and-dad music by changing tempo, kicking up through the gears until their enthusiasm ran away with them. These cats were gone.

To young British listeners, whose cultural tastes had long been mediated by the beige instincts of the BBC, such musical mischief was infatuating. Where did it come from, this exciting sound? The answer knocked them for six. Used to hearing a mixture of sugary novelty songs, ersatz pop and white-bread rhythm and blues from their native artists, many had assumed Lonnie Donegan to be American. When news got round that he was born in Glasgow and had lived most of his life in the eastern suburbs of London, many teenagers experienced an epiphany that would change their lives. For those who were there in January 1956, the name of the first British artist to get into the charts singing and playing a guitar is as evocative to them as the name of the first man on the moon is for the generation that followed.

Lonnie Donegan broke the fourth wall of Britain’s pop culture, except rather than making the audience feel that the performer was talking to them personally, his suburban background made it possible for working-class British teens to suddenly imagine themselves stepping out of the audience and into the pop pantheon. Up until this moment, most believed you had to be a trained musician to play an instrument and that everything cool and exotic in popular culture came from America. Now something sprang from the streets they walked, with an energy that threatened to upset the drab conformity of post-war Britain. A folk song played at a rock ’n’ roll tempo, on instruments you could find in your home, ‘Rock Island Line’ took things back to basics and then made them all sound brand new, British and brash.

It wasn’t only the nation’s youth who were intrigued to find a Lead Belly song in the Top Ten. The American song collector Alan Lomax, who with his father John had been responsible for discovering Lead Belly singing in Angola Penitentiary some twenty years earlier, was living in London at the time and would certainly have pricked up his ears to hear ‘Rock Island Line’ on the radio.

Born in Mississippi in 1867, Lomax senior was very much an academic when it came to song collecting. His son Alan, born in 1915, had the energy of the Machine Age about him, always looking for new technological methods to record material. Both were respected folklorists, but Alan always sought out the political context that inspired the song. For him, folk music was the unedited voice of the people and he did everything in his power to amplify the messages it contained.

In 1937, Alan Lomax, aged twenty-one, was given the first paid position at the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. The money was lousy, a little over $30 a week, but the very fact that the government was willing to pay for the people’s songs to be collected and published marked a significant watershed in American political culture.

This change in attitude was thanks in great part to Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had been elected president in 1933, with the US in the grip of the Great Depression. In his inaugural address, Roosevelt made it clear who he thought was culpable and outlined how he intended to put things right: ‘The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilisation. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than mere monetary profit.’

Key among these social values was culture. ‘The American Dream’, said Roosevelt, ‘was the promise not only of economic and social justice but also of cultural enrichment.’ When the Works Progress Administration was set up to employ people in the creation of public works, it wasn’t only infrastructure projects that were funded. As part of Roosevelt’s New Deal programme, $27 million was spent on the employment of artists, musicians, actors, writers and historians under a WPA programme known as Federal Project Number One.

Beginning in July 1935, Federal One had five components: the Federal Art Project, the Federal Music Project, the Federal Theatre Project, the Federal Writers Project and the Historical Records Survey. In the spirit of the age, the work they produced tended to glorify the strength, craft and ingenuity of American labour. Federal One money allowed Alan Lomax to organise concerts by Aunt Molly Jackson, a singer of union songs from Harlan County, Kentucky. He used the funding to record long interviews with the great Creole pianist and composer Jelly Roll Morton. He was able to hire the nineteen-year-old activist and banjo player Pete Seeger to be his assistant. And in March 1940, Lomax coaxed a recalcitrant Woody Guthrie into the Library of Congress studio to make his first recordings. The only drawback to receiving public money was that it brought his work under political scrutiny.

When the US was drawn into the Second World War following Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, an atmosphere of paranoia descended on Washington. Such was the fear of Japanese invasion that Congress passed a series of laws depriving American citizens of Japanese descent of their constitutional right to due process. Almost all the Japanese American population, around 120,000 people, were forcibly removed from their homes on the west coast and interned in military camps during the spring of 1942.

Around the same time, Alan Lomax was asked to come to FBI headquarters in Washington for what he assumed was a routine matter of increased wartime security. Instead, after being put under oath, he was interrogated about his political beliefs, particularly with regard to his relationship with the Communist Party. It was the beginning of a dark period in American history, when anyone who spoke out about inequality, racism or workers’ rights could find themselves branded a traitor. Lomax was angered by the FBI’s insinuations, but he didn’t let them deter him from promoting the people’s music. However, when the war ended and the Soviet Union emerged as America’s rival for global hegemony, those perceived to be encouraging left-wing views in the arts came under further suspicion.

The House Un-American Activities Committee was set up to investigate subversion or propaganda that attacked or criticised ‘the form of government guaranteed by the US constitution’. In 1947, the committee opened hearings into alleged communist influence in Hollywood. As a result, some three hundred artists were blacklisted by the film industry. In June 1950, the right-wing magazine Counterattack published a pamphlet entitled Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television, listing 151 figures in the entertainment world who, it alleged, were subversives. Among those on the list were Leonard Bernstein, Dashiell Hammett, Yip Harburg, Gypsy Rose Lee, Arthur Miller, Dorothy Parker, Pete Seeger, Orson Welles and Alan Lomax.

When Congress began preparing the McCarran Act, a law that would require any citizen suspected of subversive activities to register with the government which also contained provisions to prevent them from leaving the country, the atmosphere in which Lomax worked became decidedly chilly. Speaking at the Midcentury International Folklore Conference at Indiana University in the summer of 1950, Lomax put forward the idea of a series of albums that would record the ethnic music of the world. When Columbia Records offered to fund the project, Lomax took the opportunity to leave the country, sailing for Europe on 24 September 1950. He always denied that he had left to avoid being blacklisted, but in notes he made during his Atlantic crossing he bid farewell to America and his family, declaring, ‘No more fear for me now.’

Lomax found a welcome in England, where his reputation as a song collector was well known. The United States Information Service in Grosvenor Square had a record library, open to public access, that contained everything released by the Library of Congress, including Lomax’s field recordings of blues singers. Ron Gould recalls he’d often ask to hear a particular record, only to be told that it had been taken out by a Mr Tony Donegan and never returned.*

Lomax traversed western Europe, recording folk artists and scouring national sound archives, seeking material for Columbia’s World Library of Folk and Primitive Music project. He had imagined it would take about a year to complete, but it was in fact to become his life’s work.

By late 1955, he was living in London, picking up what work he could as a freelance writer and broadcaster between forays recording folk music around Britain and Ireland. When his plans for a children’s television play based on the songs of Woody Guthrie and others fell through, he took the idea to Joan Littlewood, director of the Theatre Workshop, and together they turned his script into a western-themed Christmas pantomime at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East.

Based on American folk songs, The Big Rock Candy Mountain required someone to play the role of the Cowboy, who sat at the side of the stage, singing the songs that moved the plot along. For this role, Lomax was able to call upon an acquaintance who had recently arrived from New York, Jack (later Ramblin’ Jack) Elliott. To those who encountered him on the streets of London, Elliott was the epitome of the cowboy singer: Stetson hat, lumberjack shirt, Levi jeans and western boots, carrying an acoustic guitar. And the songs he sang projected the image of a life spent drifting around the States, picking up tunes and guitar licks as he went. For audiences who had never seen a pair of Levi’s, nor heard anyone play guitar in the style of Mother Maybelle Carter, Jack Elliott was the real deal. The truth was a little more prosaic.

The son of a doctor and an elementary school teacher, Elliott Adnopoz had been born in Brooklyn in 1931. When he was nine years old, his parents took him to the World Championship Rodeo, held annually in New York’s Madison Square Gardens. Amid all the bronco busting, steer roping and trick riding, the highlight was a performance by Gene Autry, America’s top singing cowboy, who had starred in six movies in 1940 alone. After dismounting from his trusty steed, Champion, Autry sang his signature tune, ‘Back in the Saddle Again’. By the end of the evening, young Elliott had abandoned any thoughts of becoming a doctor like his father. At the age of fifteen he ran away from home to join a travelling rodeo. His parents found him and brought him home, but not before he’d been introduced to the art of storytelling and folk singing by a rodeo clown named Brahma Rogers.

When he got back to Brooklyn, Elliott, with the help of a cowboy songbook, taught himself to play guitar and was soon spending his Sunday afternoons in Greenwich Village, where fans of ‘hillbilly’ music would gather to play songs on guitars, fiddles, banjos and dulcimers. It was in this milieu that he was introduced not only to the music of Woody Guthrie, but to the man himself.

Suffering from the onset of the debilitating Huntington’s Disease that would eventually kill him, Guthrie hadn’t been in a recording studio for four years when Adnopoz first met him in 1951. By then, the nineteen-year-old was calling himself Jack Elliott and had just hitchhiked home from a trip to the west coast, singing Woody’s songs at every stop on the way. Guthrie must have seen something of himself in the youngster, because Jack was soon living at Woody’s house on Mermaid Avenue, sleeping on the couch, part babysitter, part apprentice.

The arrival of Jack Elliott gave Guthrie a chance to secure his legacy. As his condition worsened, he revealed all of his songs, stories and playing techniques to Elliott, who was only too eager to learn everything he could about the life that Guthrie had led. There was no formal teaching as such, but by watching and listening intently to what Guthrie was doing and saying, Elliott perfected all of his mannerisms, both musical and verbal.

Elliott would never become a great songwriter like his hero, but his skill lay in his ability to evoke the spirit of the songs he performed, his laconic introductions giving the impression that you were listening to him while sitting around a campfire on some cattle drive in the Old West. Crucially, he’d also gleaned Guthrie’s ability to pick up a guitar and sing for his supper without any hint of embarrassment, a skill that would stand him in good stead when he arrived in England in September 1955.

Elliott had made a lot of contacts as Guthrie’s apprentice, but he had no career to speak of, relying on busking and the occasional gig for his income as he rambled around the US in the early 1950s. His trip to Europe was instigated by June Hammerstein, an aspiring actor he’d met in Topanga Canyon. Jack was smitten and June agreed to marry him if he would take her to Europe. She figured that if he could earn some money busking over here, he’d surely be able to earn some money busking over there.

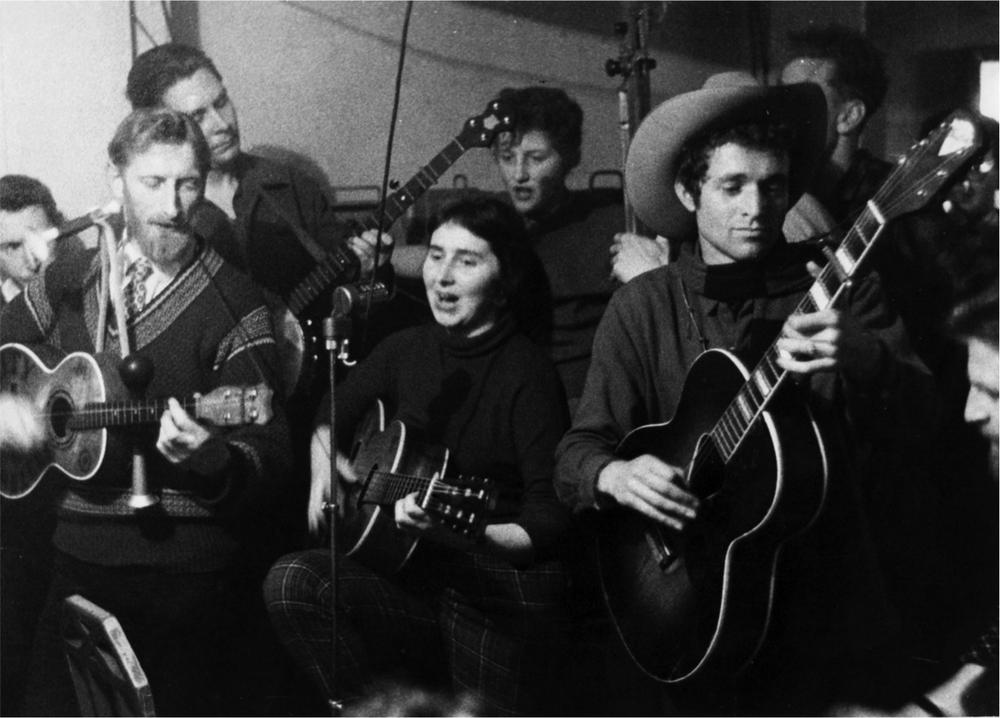

Jamming at the 44 Club, 1956: (front row, left to right) Russell Quay, Hylda Sims and Jack Elliott; John Hasted plays banjo behind Quay

With impeccable timing, the couple arrived in London at the height of the singing cowboy craze and Elliott soon found himself in demand. His first port of call was Alan Lomax, who had been one of Woody Guthrie’s earliest champions. By late 1955, the Dust Bowl Balladeer who had charmed Lomax in 1940 was a shadow of his former self, hospitalised with the incurable genetic disorder that affected his muscle co-ordination and mental function. Guthrie’s visible decline greatly distressed his friends. Powerless to help the man, they each did what they could to ensure that his music would live on. Jack Elliott, seen as Guthrie’s protégé, would be a key figure in this movement until Bob Dylan took the baton from him in 1961.

Lomax introduced Elliott to Bill Leader, who ran Topic Records, a tiny independent label that had begun life in 1939 as the record label of the Workers’ Music Association, the cultural arm of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Distributing its records by mail order, the label believed that music was a weapon to be utilised in the class struggle and featured artists such as A. L. Lloyd and Ewan MacColl. Although Topic had never released a long-playing record, Lomax convinced Leader to make an album of Jack Elliott singing the songs of Woody Guthrie. Recorded in October 1955 in the living room of Ewan MacColl’s mother’s house in Devon, the six-track Woody Guthrie’s Blues was Elliott’s first record and the only one to be released on an 8" disc.

In November, Elliott made a huge impression on music journalist Brian Nicholls, who ran into him at one of the National Jazz Federation’s monthly ‘New Orleans Encore’ concerts at the Royal Festival Hall. ‘We met a most intriguing character at the beginning of the month,’ Nicholls told the readers of Jazz Journal, ‘a real character, not one of the pseudo Bohemians one meets around town nowadays. We came across him quite by chance, singing folk blues and hillbillies. He certainly had the authentic touch, both in the material he was singing and in his appearance – a sort of non-dude cowboy outfit. The audience loved it and he certainly brought a fresh touch to the Recital Room.’

Jack’s role as the Cowboy in The Big Rock Candy Mountain garnered even greater praise. On 28 December, The Times contained a round-up of the Christmas pantomimes running in the London suburbs. There was praise for Dick Emery in Aladdin at the Golders Green Hippodrome, Puss in Boots was deemed sophisticated in Wimbledon, Arthur Askey shone in Streatham’s Babes in the Wood, and the Widow Twankey had a ‘blancmange-like resemblance to the Prince Regent’ in Aladdin at the Chiswick Empire. However, the review of The Big Rock Candy Mountain at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, was of a different magnitude altogether. Within the first paragraph, the pantomime was compared favourably with Waiting for Godot. The set has a ‘primeval quality’, the writer tells us, and the characters dream of escaping from what they love, Mother Nature. The whole thing ‘recalls the legend of the two tramps in Mr Samuel Beckett’s play’. Such high praise was somewhat tempered by the fact that the review was written by one Alan Lomax.

For his next project, Lomax was involved in a TV production of The Dark of the Moon, a play set in the Appalachian Mountains concerning two bewitched lovers. Based loosely on the folk song ‘Barbara Allen’, it had been a huge success on Broadway in the mid-40s and was now to be broadcast live in the London area as part of the ITV Television Playhouse series on 5 April 1956, starring Vivian Matalon, Paddy Webster and George Margo. In need of someone to play authentic Appalachian folk music, Lomax called on an old family friend who he knew was travelling in Europe at the time.

Peggy Seeger was the nineteen-year-old banjo-playing daughter of Charles Seeger, a pioneering ethno-musicologist and song collector, and Ruth Crawford, a composer and folklorist. Both had worked with Lomax and his father, John, at the Library of Congress in the 1930s. Peggy had grown up surrounded by folk music. Her parents’ house in Chevy Chase was always full of musicians – her half-brother Pete would come by and play banjo for her and her brother Mike when they were children; Lead Belly was a frequent visitor, as was Woody Guthrie; even the housemaid, Elizabeth Cotten, was a folk artist of considerable talent.

By the early 1950s, the McCarthyite witch-hunts had cast their shadow over the family. Pete Seeger was named in the Red Channels list of subversives, leading to his band, the Weavers, being blacklisted. Charles Seeger, who had been music critic for the communist Daily Worker in the 1930s, had the renewal of his passport turned down on the grounds that he was ‘a person supporting Communist movements’. Undeterred by such blatant Red-baiting, Peggy went to Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to study Russian. Following the death of her mother and her father’s subsequent remarriage, she was sent to Leiden in Holland to study for a year, by coincidence crossing the Atlantic on the same ship as Jack and June Elliott, the Holland America liner MS Maasdam.

Peggy was lodging with her eldest half-brother, Charles, but after falling out with her sister-in-law, she took her banjo and a knapsack and hit the road. ‘Around Christmastime 1955 I was picked up by a Catholic priest who saw the guitar and said, “I’m taking a travelling troupe of theatre performers to East Berlin. Would you like to come?” Well, I was a yes-girl and I said yes, definitely. So we picked up thirteen refugees who were fleeing communism. We brought them back to Belgium, where I was their little mother for three months. We had a tiny little two-up, two-down, and the priest started to convert me to Catholicism.’

Some friends became worried about the tone of Seeger’s letters, so they came to rescue her. ‘They found me at the table saying my rosary and they said, “We’re leaving tomorrow.” They had a little Fiat and took me to Denmark.’ She was staying in a youth hostel in Copenhagen when a call came through from Alan Lomax in London. ‘He said there’s a television programme, they’re doing Dark of the Moon, they’re on budget and they need a female who plays the banjo and, well, Alan Lomax had been in my life ever since I could remember, so that’s how I first came to England.’

‘Rock Island Line’ was still in the Top Twenty when Lomax met a thin and dishevelled Peggy Seeger at Waterloo Station on 25 March. Decca Records had a substantial hit on their hands but were unable to follow it up. They had failed to sign the Chris Barber Jazz Band to a formal record deal, preferring to pay the musicians a session fee of £75, which they split six ways, Lonnie picking up an additional fee of £3 10s. for his vocal performance on the skiffle tracks. Though his record sold over a million copies, under this deal Donegan never received a penny in royalties from the label.

Without an artist under contract, Decca were stymied. If anyone had been paying even scant attention, they might have realised that they had more material by the Lonnie Donegan Skiffle Group in their vaults – the versions of ‘Nobody’s Child’ and ‘Wabash Cannonball’ that had been recorded during the New Orleans Joys session some twenty months before. Instead, they decided to release a couple of live tracks from a Chris Barber Jazz Band concert at the Royal Festival Hall in October 1954.

Decca must have been desperate, because the A side, ‘Diggin’ My Potatoes’, was never going to get any airplay in mid-50s Britain. The song, written and originally recorded by Washboard Sam, uses euphemisms to tell the tale of a faithless wife discovered by her husband fellating another man. Not really the sort of thing you’d hear on Housewives’ Choice. It sank without trace, but not before being savaged in Jazz Journal, whose reviewer dismissed it as suffering badly in comparison to Lead Belly’s version.

What Jazz Journal failed to grasp was that the majority of teenagers who put ‘Rock Island Line’ into the charts weren’t using Lead Belly as their main reference point. To them, Lonnie Donegan was competing with the new generation of young, guitar-toting rockers coming out of the US, the latest of whom featured in an advert that ran alongside the Top Twenty in the NME during the week that Peggy Seeger arrived in Britain. Heralding the first UK release by the man the ad calls ‘The King of Western Bop’, the copy introduces Elvis Presley to British record buyers.

‘Take a dash of Johnnie Ray, add a sprinkling of Billy Daniels and what have you got? Elvis Presley, whom American teenagers are calling the King of Western Bop. He’s twenty, single, scorns Western kit for snazzy, jazzy outfits. Now he bids emotionally for recognition in Britain with “I Was the One” and “Heartbreak Hotel”.’

Snazzy? Jazzy? What kind of singing cowboy was this?

* Lonnie was unrepentant, admitting years later that he’d stolen a copy of Muddy Waters’ plantation recordings that Lomax had cut in 1941. ‘I borrowed it and never took it back. I told them I’d lost it and paid the fine … quite happily.’ The fact that he’d deprived blues fans like Ron Gould of access to Muddy’s first recordings never seemed to have troubled his conscience.