A four-engine propeller aircraft flying the London-to-New York route in the mid-50s could take fourteen hours to cross the Atlantic, with refuelling stops at Prestwick in Scotland, Keflavík in Iceland and Gander in Newfoundland, giving Lonnie Donegan plenty of time to consider how American audiences might react to skiffle. In his initial US publicity, Donegan was labelled the ‘the Irish Hillbilly’. This was a complete misnomer – ‘the Scottish Cockney’ would have been a fairer reflection of his roots – but the term linked him in the minds of the record-buying public to another guitar-strumming young artist who had just scored his first number one single.

Coming from poor white southern stock, Elvis Presley was referred to in early articles as ‘the Hillbilly Cat’. It was a fitting term. ‘Hillbilly’ suggested the old-time music much loved in Tennessee, where he was based, while ‘Cat’ implied a cool appreciation of black rhythm and blues. The label was borne out by the choice of songs that Elvis had cut for Sun Records – a mixture of bluegrass numbers like ‘Blue Moon of Kentucky’ and souped-up R & B romps such as ‘That’s All Right’. Like ‘The King of Western Bop’ and ‘The Memphis Flash’, these labels were conjured up by middle-aged music journalists trying to make sense of a new phenomenon. Sixty years after the event, the settled term for the music that Elvis was playing while he was at Sun Records is rockabilly.

In Go Cat Go!, his 1998 study of rockabilly music and its makers, author Craig Morrison produces a handy list of attributes that he believes helps to define the genre. It’s worth examining, if only for the fact that skiffle and rockabilly, exact contemporaries, had many features in common. His first criterion is that there should be an obvious Elvis Presley influence. Given that ‘Rock Island Line’ was recorded just a week later than Presley’s debut single, one can’t claim that Lonnie was looking to Elvis, but the King influenced many of the skifflers who followed in his wake.

Morrison believes that rockabilly performers should have a country music background and an awareness of the blues, and while it would be hard for British musicians to be as steeped in country as their American counterparts, Donegan, Dickie Bishop and Johnny Duncan all shared an appreciation of the old-time hillbilly music. The identifiable country and rhythm and blues inflections that Morrison cites were also present in skiffle, as were the blues structures that he highlights. Any band that numbered Ken Colyer, Lonnie Donegan and Alexis Korner among its members, as the original Colyer Skiffle Band did, was bound to contain those ingredients.

The next three items on Morrison’s list were all part and parcel of Lonnie Donegan’s style, attributes he passed on to his followers: strong rhythm and beat; emotion and feeling; a wild or extreme vocal style. Upright bass, especially if played in a slapped manner, was common to both rockabilly and skiffle, the percussive slap necessary as both Elvis and Lonnie had initially fronted trios without a drummer.

Moderate or fast tempo is another of Morrison’s criteria for rockabilly that is also a key aspect of skiffle. His narrow dating of rockabilly to the three-year period of 1954–6 echoes skiffle’s own window of success in the years 1956 to 1958. He also decrees that rockabilly must have southern origins. Is it stretching things a little to argue that skiffle emerged in the south-east of England?

That final point aside, out of the dozen rockabilly criteria that Morrison cites, only one is inapplicable to skiffle: use of echo effect. Such embellishments were available in Britain – producer Joe Meek, then a jobbing engineer, used echo on Humphrey Lyttelton’s 1956 single ‘Bad Penny Blues’ – but skifflers sought authenticity and echo sounded too much like a gimmick.

Interestingly, Morrison’s list of things that were a sure sign that a record was not rockabilly also apply to skiffle and are most helpful in identifying the pseudo-skiffle records that appeared on the market in the wake of Donegan’s success: obvious commercial intent; condescendingly juvenile lyrics; chorus groups, especially female; harmony singing; bland or uninvolved singing; saxophone; electric bass; piano, unless it is Jerry Lee Lewis; weak rhythm; black performers; slower tempos; every year later than 1957.

In early 1956, Elvis Presley and Lonnie Donegan had astounded the musical establishments in their respective countries by appearing, as if from nowhere, in the Top Ten. ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ and ‘Rock Island Line’ sounded like they came from an altogether different planet to the sugar-coated pop music of the day. In the UK, the two were perceived as rivals, and the British music papers, while somewhat sceptical of Donegan’s talents, felt they should get behind their boy, if only for patriotic reasons.

Just before Donegan left for the US, Record Mirror ran a full-page story to highlight the fact that, while Lonnie was a hit in America, Elvis Presley, whose first UK single had been released a week or two before, was failing to catch on over here. To rub in their sense of superiority, they ran a headline that parodied those beloved of US trade paper Variety: ‘Donegan Socko in States But Limeys May Say Nix on Elvis’.

Much of the British resistance to the newcomer was voiced by fans of Johnnie Ray, who felt that Elvis was a poor imitation of their idol. ‘How can Elvis Presley have the nerve to come into show business with no original ideas?’ raged Judith Marks from Edgware, Middlesex, in the NME. ‘He sings like JR, he stands like JR, but he can’t copy JR’s showmanship and sincerity.’

It would not be long before Elvis won over British record buyers, his macho swagger proving popular with young men in a way that Johnnie Ray’s tear-stained pleading never could. Meanwhile, Lonnie Donegan wasn’t quite as ‘Socko in the States’ as the NME had claimed. While sales of ‘Rock Island Line’ had taken him to a peak of number eight in mid-April, plays on radio and jukeboxes kept the single in the Billboard Top Twenty until he arrived in New York.

When Lonnie Donegan set foot in the States, Joe Boyd was a fourteen-year-old from New Jersey attending school in Connecticut and listening to Top Forty radio stations such as WINS New York and WPRO from nearby Providence, Rhode Island. In the 60s, Boyd would relocate to England, going on to work as a record producer for artists such as Pink Floyd, Nick Drake, Fairport Convention, REM and myself, but in the spring of 1956, he was intrigued to hear ‘Rock Island Line’ on pop radio. While happy to dance to Chuck Berry and Fats Domino along with his teenage contemporaries, Boyd was more interested in old blues and jazz records. As the owner of a red vinyl copy of Stinson Records’ Lead Belly Memorial Album, Volume Two, he was already familiar with ‘Rock Island Line’.

‘I had a bad attitude about white blues singers, but there was something about Donegan’s nasal voice and British accent that made it sound almost as exotic as the Lead Belly version.’ Boyd felt that the popular folk music of the period was devoid of real feeling. ‘American folk singers mostly sang corny harmonies. Lonnie’s attitude and strangely authentic sound was startling and refreshing. I was intrigued by the unselfconsciousness of his performance. I bought his LP and liked almost all the tracks. And when I heard where he was from, it helped fuel a desire to go to England.’

Boyd liked the way that Donegan inhabited the song, resisting the temptation to imitate Lead Belly. ‘Outsiders often have a more interesting take on a music than the middle class from the same culture. American artists had too many racial complexes to be that straightforward. It wasn’t until Dylan and a few of the Boston folkies like Eric von Schmidt and Geoff Muldaur that I heard white people singing black music in such an appealing way. I think it’s safe to say that from 1956 until about 1962, I resisted most white folk singers, except Lonnie Donegan.’

Other teenagers across the States were listening in too. In Queens, the first record Art Garfunkel ever bought with his own money was Donegan’s ‘Rock Island Line’. A seventeen-year-old Phil Spector performed Lonnie’s song – the first thing he learned to play on guitar – at his high-school talent contest in Fairfax, California. Down in New Orleans, Malcolm ‘Mac’ Rebennack, serving an apprenticeship with Professor Longhair that would later gain him the title Dr John, remembers being inspired by Lonnie’s hit. And Buddy Holly, whose band had already opened for Elvis and Bill Haley in his home town of Lubbock, Texas, was so impressed with ‘Rock Island Line’ that he immediately incorporated it into his set. His drummer, Jerry Allison, later said, ‘We thought it was a rock ’n’ roll record.’

The Perry Como Show was the highest rated TV show on the NBC network in 1956, regularly reaching 12 million viewers. Donegan, who’d never appeared on TV before, was thrown in at the deep end on his arrival. Having left the Chris Barber band and with no musicians of his own, he faced being accompanied by the house band wherever he was playing in the US. That was no great challenge – by upping the tempo of his guitar playing, he was usually able to drive ‘Rock Island Line’ to a rousing conclusion. But when he turned up for rehearsals at NBC, the show’s producers dropped a bombshell. The American Federation of Musicians had refused to grant him permission to play the guitar. The AFM/MU embargo may have ended, but there were still a few bumps in the road that needed to be ironed out. In the UK, this wouldn’t have been an issue. There simply weren’t enough guitar-playing singers for the Musicians’ Union to be concerned about, so when an artist like Slim Whitman toured, the union had no qualms about letting him play his instrument. The scene in the US was different. The popularity of guitar players was putting the big bands out of business. The AFM weren’t going to let some guy from England cause problems for their members.

Donegan was stunned. Here he was, about to make the biggest appearance of his career, and they weren’t even going to let him play guitar. ‘I feel naked without it,’ he complained. ‘Take away my guitar and I don’t know what to do with my arms.’ For the show, he was backed by a trio of guitar, bass and drums that included Al Caiola, who would go on to play the distinctive acoustic guitar riff that introduces ‘Mrs Robinson’. ‘They were sensational musicians and really wanted to help,’ recalled Donegan, ‘but they read my songs as country and western. They weren’t familiar with this strange music we called skiffle and just had to busk it, which was very difficult as I tend to speed up and get frantic.’

Perry Como’s star guest that Saturday night was Hollywood actor Ronald Reagan. The format of the show required Donegan to join Como and Reagan in stilted comedy sketches. The man who would go on to become the fortieth president of the United States appeared baffled by his encounter with the King of Skiffle, asking a question that may have been repeated in a number of households across America that tuned into The Perry Como Show that evening: ‘What is a Lonnie Donegan?’

The following day, Lonnie flew to Cleveland to appear on The Bill Randle Show, broadcast live on WEWS-TV every Sunday night. Randle was a hugely influential DJ who did much to introduce northern audiences to rockabilly. When Elvis Presley made his first TV appearance in January 1956 on the Dorsey Brothers’ Stage Show, the compère, fifty-year-old Tommy Dorsey, called on Bill Randle, twenty years his junior, to introduce Presley, the old bandleader seemingly fearful of taking the responsibility for unleashing the Memphis Flash into the living rooms of middle America.

Randle had cut his teeth in Detroit during the late 40s as host of a radio show called The Interracial Goodwill Hour, aimed at introducing black artists to white audiences. Randle continued in this vein after moving to Cleveland, promoting concerts at which black and white artists appeared on the same bill. The city had been a hotbed for rock ’n’ roll since local DJ Alan Freed began popularising the term on his show. Such was the appetite for rock ’n’ roll that Elvis Presley had played his first gig north of the Mason–Dixon Line in the city’s Circle Theater in February 1955.*

For his performance on The Bill Randle Show, Lonnie was backed by the Jonah Jones Quartet, led by a forty-seven-year-old jazz trumpeter from Louisville, Kentucky. Featuring piano, bass and drums, the quartet were quite at home playing the boogie-woogie and jump blues that had inspired so many of the early rock ’n’ rollers, making it much easier for Donegan to sing in his own loose style. The next day, they backed him again at a benefit concert for the Girl Scouts of America.

Returning to New York, Donegan took up a two-week engagement at the Town and Country Club, on Flatbush Avenue, where artists such as Judy Garland, Harry Belafonte, Tony Bennett and Sophie Tucker were regular attractions. The owner, Ben Maksik, liked to promote the club as the ‘Copacabana of Brooklyn’ and it had a Las Vegas feel, from the modern-art decor right down to the mob connections. During the mid-50s, Bill Graham, who would go on to find success as a promoter of rock concerts, waited tables there. He described Maksik as ‘a wiry guy with that intense Murder, Inc. face … always had six or eight half-dollars in his hand, like Captain Queeg’s ball-bearings in The Caine Mutiny. His wife Doris dressed like she was sixteen years old and the party they were having was for her. Like that year’s version of a Barbie Doll. She was at least forty years old.’

Refused permission to play his guitar, Donegan had to find a guitarist familiar with blues and American folk music who could accompany him for the two-week run. Someone came up with the idea of hiring Fred Hellerman, which, on paper, made total sense. Twenty-nine-year-old Hellerman had been a member of the Weavers, America’s premier folk band until they were blacklisted in the early 50s for their left-wing views. The group had disbanded and Hellerman found work as a record producer, arranger and publisher. Fred took the gig but came to regret it. He knew Lead Belly, and had a huge respect for him and his songs – he’d even sung at Huddie’s funeral. He was a close friend of Woody Guthrie, too. He didn’t appreciate what this Brit upstart was doing to their material: messing with the lyrics, rocking it up, ignoring the context. He didn’t much care for the audiences Donegan drew either, kids with no appreciation of roots music who saw him as one of those flashy guys with a guitar promising a break with the past.

‘They were not a folk music crowd,’ Hellerman recalled of the teenagers who came to see Donegan at the Town and Country. ‘They were less primed than the audiences who came to see the Weavers. They just listened, they didn’t join in.’ As for Donegan, ‘He had little sense of what these songs meant. He was looking for a pop audience and doing it very badly.’ Lonnie may have been selling coals to Newcastle when he got American teenagers to buy ‘Rock Island Line’, but in Fred Hellerman he found himself confronted by a local collier who didn’t take kindly to seeing his wares being hawked in such a trashy manner each night.

There were others who also questioned Donegan’s intentions in recording old blues songs. On 9 July 1956, Billboard reported that NBC’s National Radio Fan Club had initially refused to play his new single, ‘Lost John’, on the grounds that his delivery of the lyrics amounted to racial stereotyping. Under the headline ‘Intent Saves Donegan Disc’, the report went on to explain that producer Parker Gibbs was able to convince the network’s censorship department ‘that the English singer is on the level and not doing an Amos ’n’ Andy’. The story was deemed serious enough to merit appearing on the front page.†

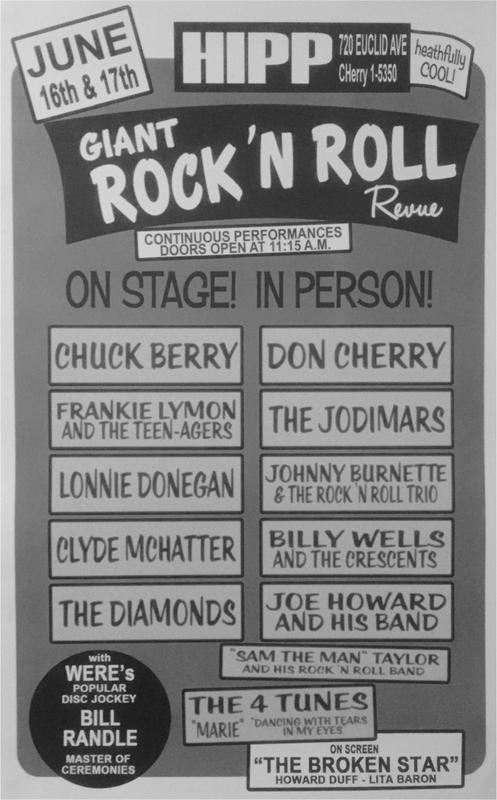

Hellerman declined the opportunity to accompany Donegan on a ten-week tour of the States that saw him playing on a rock ’n’ roll package show with artists such as Chuck Berry, Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers and Clyde McPhatter. By this time, Lonnie had received permission to play his guitar but he still had a mountain to climb. ‘All the coloured acts were backed by an orchestra but I had no parts [for the musicians to play] as I’d come from a jazz band. I was alone with a little Martin guitar.’ The show was run as a continuous revue, doors opening at 11.15 a.m., five performances each day, with Donegan singing ‘Rock Island Line’ and ‘Lost John’. ‘It was ridiculous, I felt like a human sacrifice.’

A poster for Lonnie Donegan’s June 1956 gig in Cleveland, Ohio

During a five-day stint at the Fox Theatre in Detroit, Donegan finally found some kindred spirits. Also on the bill were the Rock ’n’ Roll Trio, a rockabilly band from Memphis. Led by Johnny Burnette, they are now considered the only real rivals to Elvis Presley during his Sun Records days. Johnny played guitar and sang with a holler and a growl, his brother Dorsey played bass and the line-up was completed by Paul Burlison, the king of the rockabilly guitarists. Their performance consisted of a three- or four-song set, usually containing their one regional hit, ‘Tear It Up’, along with ‘Your Baby Blue Eyes’, ‘Tutti Frutti’ and ‘Train Kept a-Rollin’’, which featured Burlison’s trademark lick – playing a solo by plucking both the highest and lowest strings at the same fret.

On the second day of the show, Johnny Burnette approached Donegan. ‘We love what you’re doing, man. Can we come out and play with you?’ Ever conscious of the bottom line, Donegan told him it was a great idea but he couldn’t afford to pay them. ‘Who said anything about money?’ replied Burnette. ‘Man, we just want to play with you.’ Donegan was flattered. ‘I said, “Great,” and from then on, they were my backing group. Dorsey Burnette played slap bass and Paul Burlison played like Elvis’s guitarist, Scotty Moore, and Johnny slashed the guitar like me and sang like a cross between me and Elvis. We enjoyed ourselves after that.’

During that week in Detroit, skiffle and rockabilly met on equal terms and were amazed to discover that, although they were born on opposite sides of the ocean, they were so alike as to be brothers. When Donegan finished his first round of touring, he flew Maureen out to the States and together they visited Johnny and Dorsey Burnette in Memphis. They were taken on a fishing trip, held a midnight barbecue where guitars were pulled out and songs sung, and Johnny even took Lonnie to meet his old pal, Elvis, who, sadly, was out of town. After Memphis, the Donegans made a pilgrimage to New Orleans, seeking out the old-style jazz still played in the French Quarter.

His American manager, Manny Greenfield, wanted Donegan to join another ten-week package tour, but he had had about as much as he could take of the five-shows-a-day treadmill. In comparison with the UK – a country which, at the time, had one radio station and two TV channels – the promotional demands of US television and radio were exhausting. Having begun by chatting with the future president of the USA, Donegan had ended up being introduced by a ventriloquist’s dummy named Knucklehead on a Saturday-morning kids programme hosted by Paul Winchell, a popular act who, in another life, would provide the voice of Tigger in Walt Disney’s Winnie the Pooh. It was all too much. And anyway, his British management were desperate for him to come home. ‘Lost John’ was headed for the top of the singles charts.

* Eight months later, Presley returned to play a show organised by Randle at the Brooklyn High School in Cleveland’s south-western suburbs, a gig that some Elvis scholars cite as a catalyst for his meteoric rise to fame. Randle was being filmed for a documentary entitled The Pied Piper of Cleveland: A Day in the Life of a Famous Disc Jockey and, sensing that Presley was on the verge of becoming a national sensation, he had them film Elvis, backed by Scotty Moore and Bill Black, as he whipped the crowd of high-school teens into a frenzy with ‘Mystery Train’, ‘That’s All Right’, ‘Blue Moon of Kentucky’ and ‘Good Rockin’ Tonight’. Randle mentioned the film when introducing Presley on the Dorsey Brothers’ show, yet it never saw the light of day. Rumours abound as to why the film was never released. Some even question its existence. The Pied Piper of Cleveland has become something of a holy grail for Elvis fans.

† Amos ’n’ Andy was the title of a radio comedy that ran from 1928 to 1955, concerning the adventures of two poor, uneducated African Americans who had left the south to seek work in New York. Written and performed by two white actors, it took its cues from the minstrel tradition, relying on negative racial stereotypes for comedic effect. Donegan’s spoken introduction to ‘Lost John’ was his respectful homage to Lead Belly, but, in his attempt to imitate his hero’s delivery, he had unwittingly strayed into a racial minefield. Fortunately for him, cooler heads prevailed and the people at NBC recognised his sincerity.