Lonnie Donegan began 1957 on a wave of popularity. If the appearance of his debut album in the singles charts seemed incongruous, then Tin Pan Alley must have been dumbfounded when he came second in the NME’s annual popularity polls. Elvis had only managed third behind Frank Sinatra and Johnnie Ray in the American Male Singer category, but Lonnie snuck in between big-band leader Ted Heath and crooner Dickie Valentine, who took the title of Most Outstanding British Musical Personality.

It wasn’t just Donegan who was suddenly outstandingly popular. The Daily Herald reported jam-packed crowds of ‘duffel-coats and horsetails’ gathering in Orlando’s, Johnny Grant’s deli/coffee bar just a few doors along Old Compton Street from the 2 I’s. The article carried a picture of the Ghouls skiffle group performing among the salami and olive oil. Bearded boho Fath Maitland, the group’s leader, explained how he and some friends had asked Grant if they could play in his shop for fun, only to find a few weeks later that they now needed a doorman to keep the crowd outside from blocking the pavement.

Despite complaining that all the songs sounded the same, the journalist reported that there were now four other skiffle bars in Old Compton Street alone, with about twenty in Soho and more further afield. Nineteen-year-old Joan Pike, who was taking the hat around for the Ghouls, told the Herald that the attraction of Orlando’s was that it provided teenagers with ‘a place of our own, where dreary, old middle-aged people in their thirties won’t bother us’.

The Ghouls perform amid the salami at Orlando’s

Ken Sykora, writing in Music Mirror, noted approvingly that the Ghouls were known to nip next door to the 2 I’s and borrow a spare guitar string from the Vipers. The emergence of Tommy Steele from the skiffle scene and Donegan’s continued success meant that doors began opening for skiffle groups, and the Vipers were among the first to benefit. Having passed on signing Tommy Steele, George Martin, the youngest record company executive in town, signed the Vipers to his Parlophone label in October 1956 and produced their debut single at Abbey Road.

Martin’s genius was to resist bolstering the group’s sound with professional sidemen from the swing bands that provided the pool of session musicians working on the pop records of the day. There were no jazzy guitar chords seeking to soften the sound for the Light Programme on the Vipers’ records, just three fiercely strummed acoustics, backed by a rockabilly bass line and John Pilgrim’s lap-played washboard. Martin created the first record to contain the real sound of skiffle, as heard in the basements and cafes of Soho. The Vipers were much admired by skiffle fans, not least because their no-frills approach to recording conveyed the idea that anybody could make this music.

Lonnie Donegan’s success had catapulted him from the back of Chris Barber’s Jazz Band to the top of the bill at ATV’s prime-time variety show, Sunday Night at the London Palladium. He was seen on TV dressed in a dark suit and bow tie, playing his acoustic, but now backed by an electric guitarist and a jazz drummer. By contrast, the Vipers looked like they’d just been busking outside the Palladium. Twenty years before punk rock made a fetish of the DIY approach, the Vipers’ authenticity endeared them to a generation of skiffle fans in their early teens.

Like Donegan, the Vipers plundered Lead Belly’s repertoire for their first single. The A side was an up-tempo run through the old spiritual ‘Ain’t You Glad’, backed with the African American work song ‘Pick a Bale of Cotton’. The latter had first been recorded by John and Alan Lomax at Sugarland prison farm in December 1933, performed by a sixty-three-year-old inmate named James ‘Iron Head’ Baker, whose ability to both recall and improvise a vast number of songs led John Lomax to dub him a ‘black Homer’.

The Vipers’ debut single didn’t trouble the charts, but in January 1957 they released a song that would come to define the skiffle movement. With its infectious chorus and call-and-response verses, ‘Don’t You Rock Me Daddy-O’ had been transformed by George Martin from a sea shanty into a clarion call for the coming war of the generations.

Now that it had been commercially released, there was nothing to prohibit Lonnie Donegan recording his own version. Featuring a brief drum solo and a burst of jazzy lead guitar from Denny Wright, this was a polished pop song and duly rose to number four in the charts. The Vipers’ original, sounding, by contrast, like it was recorded in the invigorating confines of a crowded coffee bar, only managed to reach number ten, but this was enough to put them on the map. The second skiffle group to make the charts, they soon found themselves in great demand, following Donegan and their erstwhile bandmate Tommy Steele onto the variety circuit, where they were welcomed with open arms.

As the independent television network was becoming more populist in order to differentiate itself from the highbrow BBC, it naturally began to feature more variety comedians in its lighter programming. The effect was soon felt in the theatres. Why go out on a wet Wednesday to a draughty old music hall and pay to sit through a series of antiquated vaudeville acts when you could watch them all in the comfort of your own home for free? Desperately in need of new blood, the variety promoters grabbed skiffle with both hands.

The Vipers first trod the boards at the Prince of Wales Theatre, just off Piccadilly, where for two weeks they shared a spot just before the intermission with the Bob Cort Skiffle Group. Top of the bill was blonde bombshell and TV singing star Yana, a former hairdresser’s assistant from Billericay in Essex whose real name was Pamela Guard. The rest of the bill was filled with the usual comics and animal acts, although history doesn’t record whether Bob Hammond ‘and his Feathered Friends’ were the former or the latter. Being placed in the middle of the batting order allowed the skifflers to carry on with their regular gigs in the late-night cafes and clubs of the West End.

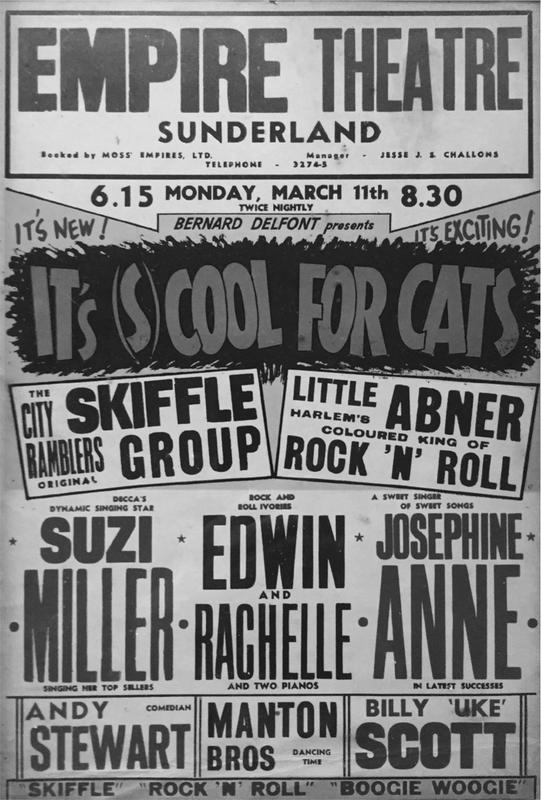

Around the same time that the Vipers were commencing their engagement at the Prince of Wales, the City Ramblers, returning from their European jaunt to find the skiffle craze in full swing, undertook a national variety tour under the banner ‘It’s (S)Cool for Cats’.* Promoter Bernard Delfont was trying hard to draw the teenage audience into his theatres. The poster advertising the City Ramblers’ week at the Sunderland Empire promised ‘Skiffle’, ‘Rock ’n’ Roll’ and ‘Boogie Woogie’. When the tour reached Hull in mid-March, it had become ‘Britain’s First Ever Rock ’n’ Roll Tour’. In truth, it was just another variety bill, albeit one without any dog acts or trick cyclists: the Manton Brothers did the soft-shoe shuffle, Billy ‘Uke’ Scott strummed his ukelele and comic Andy Stewart was the MC. The only real hint of rock ’n’ roll on the bill came from Little Abner, a singer and boogie-woogie pianist in the style of Big Joe Turner, born Abner Kenon in Florida in 1917. As a subtle warning to those of a nervous disposition, Delfont made sure audiences realised that they were about to see a black man on stage by billing Little Abner as ‘Harlem’s Coloured King of Rock ’n’ Roll’.

(S)Cool for Cats. Skiffle on the variety circuit, 1957

On 21 January, a new combo, the Chas McDevitt Skiffle Group and Nancy Whiskey, made their debut in variety at the Metropolitan in London’s Edgware Road, on a bill which included three comedians, a juggling duo, a balancing act and the 3 Quavers, intriguingly described in the programme as ‘instrumentally different’. McDevitt was born in Glasgow in 1934 and had been playing banjo with the Crane River Band, Ken Colyer’s original outfit, recently re-formed with new members and performing regularly at Cy Laurie’s. Chas led the breakdown group.

In late 1956, McDevitt’s skiffle group entered a talent contest on Radio Luxembourg and came top for four weeks in a row. Nancy Whiskey, who had taken over running the folk and skiffle night at the Princess Louise while the City Ramblers were rambling across Europe, also appeared on the programme, and the group’s manager duly took note. Bill Varley – he who had snaffled a co-writing credit on ‘Don’t You Rock Me Daddy-O’ for simply introducing Wally Whyton to a publisher – understood that, if they were to make their mark, the McDevitt group needed a gimmick. And, in the exclusively male world of skiffle, what better gimmick than a girl singer?

McDevitt wasn’t enamoured of the idea, feeling it suggested that Bill Varley had no confidence in the act, while Whiskey preferred to sing traditional Scottish songs. However, it was clear to everyone in the Soho scene that skiffle was taking off, so Whiskey agreed to join McDevitt’s group for six months.

Their first joint recording was a song that McDevitt had originally heard performed by Peggy Seeger. As a result of her folk-infused upbringing and her time at university, Seeger’s repertoire differed from those of performers on the London skiffle scene, who had mostly learned their material from commercial recordings. ‘Both my brother Pete and I went and looked up songs when I was at Radcliffe, which was the female section of Harvard. I would go into the Harvard Library and get out all the old anthologies and I’d learn songs from them.’

However, one of the stand-out songs in her repertoire hadn’t come from the anthologies compiled by her musicologist parents, nor from the library at Harvard. Seeger had learned ‘Freight Train’ from an African American woman who was housemaid at her family’s Washington, DC residence. Born in North Carolina in 1895, Elizabeth Cotten was hired by the Seegers in 1945, after she found Peggy wandering alone in Woodward and Lothrop, Washington’s largest department store, and returned her to her mother. ‘Libba would have come probably when I was ten,’ recalls Seeger, ‘but it wasn’t until I was about fourteen that I came into the kitchen and found her playing the guitar that always hung on the wall. Up until then, whenever you came in the kitchen she was ironing or she was cooking or she was putting dishes away or whatever.’

Cotten had played since childhood, initially mastering the banjo and then moving on to the guitar. Being left-handed, she developed her own distinctive picking style to allow her to play guitars strung for right-handed people. However, she had ceased playing after joining the church in the early 1920s. Working in a house full of musicians had encouraged her to pick up the instrument again, and she began entertaining the Seeger children with songs she’d played as a child, among them one she’d composed herself, ‘Freight Train’. With its mournful lyrics concerning the killing of a friend, a hanging and a burial, it must have sounded like a classic American murder ballad when Peggy Seeger played it in the coffee bars and skiffle clubs of Soho. And in the febrile atmosphere that followed Lonnie Donegan’s runaway success with what everyone assumed to be a traditional railroad song, it was only a matter of time before someone exploited Seeger’s repertoire.

Denny Carter, one of the guitarists in the McDevitt group, told Pete Frame how he ‘collected’ it one evening at the Princess Louise. ‘I’ve got a very good ear for a melody – once a song has been sung, I know it. So I concentrated on the tune, Chas noted the chord shapes and sequences, and the girlfriend scribbled the words down.’

Chas McDevitt had already recorded a version of ‘Freight Train’ in late 1956, before Nancy Whiskey came onboard. At Bill Varley’s suggestion, they recut the song, playing the tune in double time. With Nancy’s chirpy vocal and Chas whistling a harmony line between each verse, they transformed a dark tale of evil deeds into a catchy pop song.

‘Freight Train’ was released as a single in January 1957 and initially got little attention, but during March the band took part in an extensive tour of British theatres, opening for Slim Whitman. There were no variety artists on this bill, just Slim, the McDevitt Skiffle Group and Nancy Whiskey, and Terry Lightfoot’s Jazzmen, a blues-influenced trad band. This was enough to propel ‘Freight Train’ into the charts by mid-April, beginning a run of seventeen weeks that saw the single peak at number five.

They followed the Whitman tour by joining with Lightfoot again to open for American sensations Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, touring on the back of their UK number one hit, ‘Why Do Fools Fall in Love?’. Again, there were no cheesy variety artists to get in the way of the stars. This was a bill aimed exclusively at those under twenty: nothing but trad, skiffle and rock ’n’ roll.

But the big sensation of early 1957 was the arrival from the US of Bill Haley and His Comets for their first UK tour. The Daily Mirror took a bunch of teenagers to Southampton to meet the band at the dockside and chartered a special train to take them to London, where fans thronged the station to see their hero. But what they saw puzzled them. In the flesh, Bill Haley was a portly, middle-aged father of five who looked more like one of the square teachers in Blackboard Jungle than one of the too-cool-for-school kids. He didn’t seem to have realised that James Dean had reset the image of the teen idol as a potent mixture of moody, sexy and rebellious. Haley was none of these and, although the tour was a huge success, it all but killed his career.

Since ‘Rock Around the Clock’ reached number one in October 1955, Haley had scored nine Top Twenty hits in the UK; after his British tour, he didn’t manage to get another single in the charts until March 1974 – ironically, a reissue of his original hit. For all the tumult he had caused, Bill Haley wasn’t the King of Rock ’n’ Roll after all. He was the herald, and ‘Rock Around the Clock’ the clarion call, alerting the first generation of British teenagers to the coming of the One True King, Elvis Presley.

Now that Tommy Steele had shown that English kids could play rock ’n’ roll too, everyone wanted a piece of the action. Paul Lincoln, at the 2 I’s, kept his ear out for another teenager who could sing like Elvis among the crowds who thronged to his cafe every night. Terry Williams, a seventeen-year-old from south London, had been singing rock ’n’ roll songs in the boiler room of the HMV record plant where he worked. He liked the way the natural echo made his voice sound like Elvis. One night he took his guitar along to the 2 I’s and asked if he could sing a song. His version of ‘Poor Boy’ from the soundtrack of Presley’s first movie, Love Me Tender, so impressed Lincoln that he took Williams under his wing, changing his surname to Dene (after James Dean).

Quickly finding an agent for his new charge, Lincoln staged what may have been the first all-British teenage package show, at Romford Odeon, on the outskirts of London, on 31 March 1957. Terry Dene made his debut supporting the Chas McDevitt Skiffle Group and Nancy Whiskey, backed by rockers Rory Blackwell and the Blackjacks. Lincoln astutely used the popularity of skiffle to blood his would-be rock ’n’ roll idol.

The fact that skiffle had crossed over into the mainstream was evidenced on Easter Monday 1957, when ‘London’s First Big Skiffle Session’ was held at the Royal Festival Hall. The afternoon event featured a number of artists who had emerged from the jazz scene following the success of ‘Rock Island Line’.

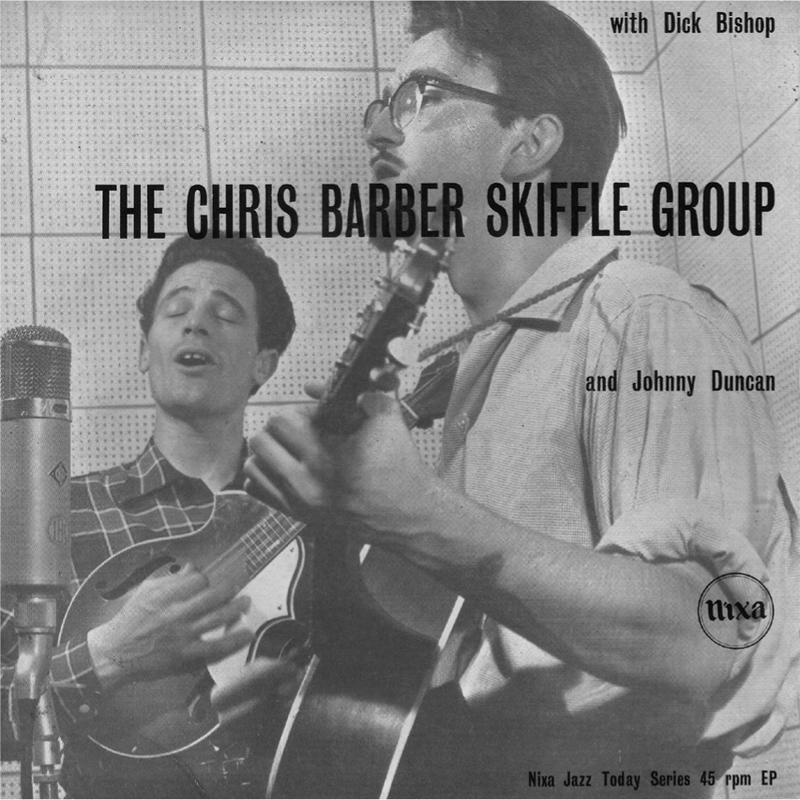

After Lonnie Donegan left the Chris Barber Jazz Band in May 1956, Barber had been wondering how to replace him, when, one night, Johnny Duncan walked into the 100 Club looking like a younger Lonnie and wearing almost exactly the same clothes. Johnny was born in Oliver Springs, Tennessee, in 1932 and had married an English girl while stationed in East Anglia with the US Air Force.† He played guitar and mandolin and sang in the high-pitched tones of a traditional bluegrass singer. He was soon sharing vocal duties with Dickie Bishop in the Chris Barber Skiffle Group.

In September 1956, Denis Preston took them into the studio to record an EP for the Nixa Jazz Today series, with pleasing results. The closeness of the harmonies and Duncan’s mandolin playing pushed the songs in the direction of bluegrass duos such as the Louvin Brothers and the Blue Sky Boys. It sounded great, but was it really skiffle? Barber didn’t think so. He’d booked a tour with Big Bill Broonzy and Brother John Sellers and needed his skiffle group to sound more bluesy.

In February 1957, Duncan jumped ship before he was pushed. Having lost Bishop to Donegan’s band some three months before, Barber, who had been midwife to the skiffle boom, decided not to replace either guitarist, quietly dropping the skiffle interludes in his set just as the craze was taking hold. However, his commitment to American roots music remained undimmed, and in the following decade he brought over the finest American blues musicians to tour with his band, acting as midwife again, this time to the blues boom of the early 1960s.

By the time of the Easter Monday Skiffle Session, Dickie Bishop had left Lonnie Donegan’s Skiffle Group after just three weeks in the job and formed his own group, the Sidekicks. Another escapee from Donegan’s band, guitarist Denny Wright, had joined Johnny Duncan and His Blue Grass Boys. Both groups were on the bill at the Festival Hall that afternoon, along with Bob Cort, a bald and bearded twenty-seven-year-old advertising man from Loughborough. Despite being also-rans in the skiffle craze, the Bob Cort Skiffle Group included key figures from the scene. Guitarist Ken Sykora would go on to host Guitar Club on the BBC Light Programme from July 1957, encouraging listeners to play in styles ‘from Spanish to skiffle’, and the washboard player was none other than Bill Colyer, the Godfather of Skiffle himself.

Bob Cort’s claim to fame is that he recorded the original title song for Six-Five Special, but for my money his cover version of Chuck Berry’s ‘School Days’ deserves recognition for sheer chutzpah alone. ‘Hail, hail, skiffle and roll, deliver me from the days of old!’ he cries, unconvincingly, while Ken Sykora fires off jazz runs on electric guitar. ‘Long live skiffle and roll, the beat of the washboard loud and cold!’ The kids weren’t biting. Cort looked like an off-duty geography teacher and sang like one too.

Also on the bill were the Avon Cities Jazz Band, who, like the Colyer and Barber outfits, had their roots in the late 1940s. The band’s clarinettist, Ray Bush, led the skiffle group that recorded eight tracks for Decca subsidiary label Tempo in June 1956. Hailing from Bristol, they differed from the standard skiffle group by featuring both banjo and mandolin.

Chas McDevitt, whose group were headliners that day, recalls the Avon Cities provided a much-needed rhythmic anchor during the final ensemble number, ‘Momma Don’t Allow’. After the sound of a dozen or so heavily strummed guitars and the metallic scrape of the half-dozen washboards involved in the encore had subsided, it was the Avon Cities who played a passable version of the National Anthem to close the event, something beyond the capabilities of many of the assembled skifflers.

In the spring of 1957, Chas McDevitt had emerged as the first real rival to Lonnie Donegan for the title of King of Skiffle. But while ‘Freight Train’ reached number five in the charts in April, the following month saw the first skiffle number one.

Cumberland Gap is the name of the only pass through the Cumberland Mountains, long known to Native Americans and discovered by European settlers in the 1670s. It provided a route through the Appalachians to Kentucky from Virginia, and the song of the same name is thought to have originated in the area around the end of the nineteenth century. The earliest recording of the song with lyrics, made by Gid Tanner and his Skillet Lickers in 1926, still evidenced its roots as a fiddle song, with Tanner throwing in the occasional stanza between longer instrumental passages. By the time Woody Guthrie recorded the song in 1944, the chorus declared that Cumberland Gap was seventeen miles from Middlesboro, Kentucky.

In early 1957, the Vipers got hold of the tune and declared that the distance to Middlesboro was in fact nineteen miles. The discrepancy may be down to how fast you’re travelling – Lonnie Donegan’s high-tempo version, released just after the Vipers’ single, claimed the distance was only fifteen miles. Using his trademark runaway-train style of delivery and with his backing group frantically skipping between the two chords that make up the entire song, Donegan accelerated past the Vipers to score his first number one.

He followed it up with a live single taken from his week’s residence at the London Palladium with the Platters. ‘Gamblin’ Man’ offers some insight into the intensity with which Donegan performed during this period. The song begins with a slow introduction but soon takes up a relentless rhythm, which has Donegan gasping for air at the start of each line. Halfway through his voice pushes up a gear as the tempo of the song gathers. He calls up a guitar solo that threatens to run out of control, before returning to sing with raucous abandon. The audience go wild.

If Lonnie dipped into the repertoire of skiffle hero Woody Guthrie for this tour de force, the song he paired it with as a double A side was much more in the variety tradition. ‘Puttin’ on the Style’, first recorded by Vernon Dalhart in 1926, is a sardonic commentary on the youthful fashions of the day. Donegan updated the lyrics and struck a chord not only with the teenagers in his audience, but also with the parents accompanying them to the Palladium show. Their teenage years had been lived during the Great Depression and the Second World War, when style had been on ration. Donegan, already pushing thirty and perhaps eyeing a potential audience of mums and dads beyond the skiffle craze, gave them a wink to let them know that he too looked askance at the fashions and fandom of the children they’d raised. The single duly went to number one, becoming both the first double A side to top the charts and the first live recording to do so.

Between these successive number ones, Donegan had returned to the States for a second tour. The reciprocal touring agreement between the UK Musicians’ Union and the American Federation of Musicians required a like-for-like swap of artists, so when Bill Haley and His Comets were booked for their British tour, there was only one act who could be sent to America in exchange. But while Haley was met with adulation wherever he went, Lonnie found himself providing a half-time show for sports fans, performing on a nationwide tour by the Harlem Globetrotters. In basketball arenas with dreadful acoustic properties, Donegan played to ten thousand people buying popcorn, some of whom complained that the Globetrotters didn’t have their usual comedian entertaining the crowds. The schedule was gruelling – nineteen cities in nineteen days, each of them hundreds of miles apart.

Donegan wasn’t the only skiffler to visit the US in the summer of 1957. ‘Freight Train’ proved just as irresistible to Americans as it did to Britons. The Chas McDevitt Skiffle Group with Nancy Whiskey reached number forty in the Billboard charts in the second week of June. Fresh from a cross-Channel skiffle and rock day trip organised by Paul Lincoln and billed as ‘The 2 I’s Rock Across the Channel’, Chas and Nancy found themselves performing on The Ed Sullivan Show in New York – fronting a group of US musicians insisted upon by the AFM, among them Hank Garland, who would later play on a string of Elvis Presley’s singles, including ‘(Marie’s the Name) His Latest Flame’. Without the necessary work permits, the only appearance they made was at Palisades Park, just across the Hudson from New York City, where they had to follow a guy who jumped off an eighty-foot tower into a pool of water – on a horse.

The success of ‘Freight Train’ in America caused the inevitable copycat versions to be released, just as Donegan had experienced with ‘Rock Island Line’. But unlike Lonnie, the McDevitt Group was not able to hold off the competition, most notably from carrot-topped country crooner Rusty Draper, who reached number eleven with the song.

The song’s popularity caused a good deal of consternation in the Seeger family, who were surprised to hear a song written by their sixty-two-year-old housemaid being played on the radio and TV, given the fact that she had no publishing deal with which to collect royalties. Their concerns grew when, on looking at the record label, they found the song was credited not to Elizabeth Cotten but to Paul James and Fred Williams, a songwriting team from England.

Ed Sullivan meets skiffle, New York, 1957: (left to right) Marc Sharratt, Ed Sullivan, Nancy Whiskey and Chas McDevitt

This wasn’t the first time British skifflers had run into trouble with US publishers. Legend has it that Lonnie Donegan’s American manager, Manny Greenfield, went to see the boss of Folkways Records, Moe Asch, to complain that one of Folkways’ artists, a certain Mr Lead Belly, was recording Lonnie’s songs without permission or payment. Moe threatened to break the allegedly offending records over Manny’s head.

Pete Seeger led the campaign to get proper recognition and royalties for Elizabeth Cotten and, in the ensuing litigation, it transpired that the pair who claimed to have written the song, James and Williams, were none other than Chas McDevitt and his manager, Bill Varley, for whom purloining credits was becoming something of a habit. The case was eventually settled amicably out of court, and Elizabeth Cotten went on to record an album of original material in 1958, produced by Mike Seeger.

Problems with visas prevented the Chas McDevitt Skiffle Group from playing concerts in the US, but they returned home to a record-breaking tour of the Moss Empires variety circuit, during which their second single, ‘Greenback Dollar’, edged into the Top Thirty. By the time the tour ended, Nancy Whiskey felt she’d come to the end of her six-month commitment to skiffle and returned to singing traditional Scottish material, complaining to the music press that she never liked skiffle anyway.