If the number of skiffle acts reaching the charts and crossing the Atlantic can be counted on the fingers of one hand, then those playing skiffle at grassroots level were legion. It is estimated that there were between thirty thousand and fifty thousand active skiffle groups at the height of the craze in 1957. ‘Skiffle’ guitars could be purchased by mail order for as little as £6 6/-. The difference between a regular guitar and a ‘skiffle’ model was never explained in the adverts, but if you couldn’t afford the full price, the guitar would be mailed to you for five shillings up front (plus five shillings postage and packaging), to be followed thereafter by twenty-two fortnightly payments of six shillings and sixpence.

Ben Davis, managing director of one of Britain’s biggest wholesale and retail musical instrument firms, told the News of the World that demand for guitars had increased tenfold since September 1956. ‘At Christmas people were walking around Charing Cross Road with bundles of notes in their hands looking for guitars. At the moment I have twenty thousand on order and wish I could get more. I estimate that this year over a quarter of a million will be imported into this country, compared with about six thousand in 1950.’

The craze reached far beyond the capital. Jim Reno, owner of Reno’s music store in Manchester, one of the largest in the north of England, declared, ‘I cannot cope with the demand for guitars, with young lads in here every day asking for them. One day last week I sold one hundred guitars.’ Bell Music of Surbiton in Surrey offered a ‘Skiffle Basselo’, a cello-sized double bass with two strings, for just £3 down and twenty-four monthly payments. Hidden in the small print was the full price, twenty-nine guineas (£30 9s.) – an expensive piece of kit in 1957, when the average weekly take-home pay for a manual worker was just over £20.

For those not able to stretch to a basselo, John Hasted printed a handy guide to constructing your own tea-chest bass in the pages of Sing magazine. The same December 1956 issue carried an article entitled ‘How to Build a Lagerphone’. An Australian invention – with, it was claimed, roots in medieval Turkey – the lagerphone consisted of three hundred lager bottle tops attached to a broom pole in such a way that they rattled when the bottom of the pole was bounced on the floor.

Hasted used his columns in Sing to defend skiffle from ‘supercilious critics who clutter up the newspapers and magazines’. He argued that it was a people’s music, with its own momentum, independent from the commerciality of the music business, and that playing guitar had empowered youth to find its voice. ‘There must be over four hundred skiffle groups in London alone,’ he reported with glee in spring 1957. ‘Local competitions receive entries from about ten groups in every borough.’

Hasted also understood that, to overcome its limitations, skiffle had to progress beyond its original canon, presciently predicting how it would lead to the British blues boom. ‘Unlike the older skiffle groups, the new ones make no distinction between a rock ’n’ roll number and a folk song and I think this is only to be expected and is not a bad thing anyway. The groups will get very tired of the rock ’n’ roll up-tempo twelve-bar and turn to the real blues if they’ve got it in them.’ He also cautioned those who, gripped by the skiffle craze, looked to take the short cut to guitar playing. ‘Don’t take the easy way out with your guitar by fixing that German machine to the neck, to get the press button chords. Within a few months you’ll find that it limits your style severely.’ He was referring to an oblong contraption that clamped onto the fretboard of the guitar, near the headstock. On top were a series of buttons marked with the names of half a dozen guitar chords in the same key. When you pressed a particular button, felt pads would hold down the strings in the correct shape for the chord, allowing you to strum a song without learning how to actually play the guitar.

Others were not so enthusiastic about the rise of this do-it-yourself music. On 9 March 1957, Melody Maker put skiffle on trial: ‘What IS skiffle? Is it a creative music, a menace or just a form of rock ’n’ roll?’ Chris Barber gave the purist’s view: ‘I regard skiffle as important only in so far as it relates to the origins of jazz.’ Tommy Steele opined that, although he once played skiffle in coffee houses, what he was playing now was something else. ‘People say skiffle appeals to the same audience as rock ’n’ roll. That’s not true. Skiffle is more intellectual.’ Bill Colyer, now playing occasional washboard with the Bob Cort Group, pleaded guilty to giving skiffle its name, but warned the critics not to look down on the craze. ‘It’s well known that today skiffle sells to rock ’n’ roll and Presley fans. That’s no reason though for anyone to get smug and self-righteous.’

Unfortunately, Melody Maker journalist Bob Dawbarn’s horse was far too high for him to hear Bill Colyer’s words. ‘Skiffle is the dreariest rubbish to be inflicted on the British public since the last rash of Al Jolson imitators,’ he fumed, sounding like Tommy Steele’s grandad. ‘Let’s face it, skiffle has as much to do with jazz as rock ’n’ roll, Guy Lombardo and ballroom dancing. Like the other three, it is a bastardised, commercialised form of the real thing, watered down to suit the sickly, orange-juice tastes of musical illiterates.’ Dawbarn was no doubt mumbling that last phrase under his breath five years later when, as editor of Melody Maker, he had Bob Dylan thrown out of the paper’s office.

The summing up for the defence came from Lonnie Donegan: ‘I did it from the beginning because I believed in it. Chris Barber, Ken Colyer and I forced it on the public in the face of early hostility. We felt that it illustrated the origins of jazz. None of us did it to make easy money.’

Since he had been crowned King of Skiffle, defensiveness had become a reflex action for Lonnie. Many of the jazzers who used to respect him during his Barber band days were bemused by his sudden elevation to matinee idol. Melody Maker itself wasn’t sure how to handle him. One week he was on the front cover with banner headlines announcing his season at the London Palladium, then a few weeks later he found the paper accusing him of being conceited. ‘It’s all very well, some say, for a star to act like a star – but [Donegan] is a mere skiffler, a man swept to accidental fame by a teenage craze.’

The old sweats at Melody Maker, unsettled by a music industry increasingly dominated by teenage tastes, were constantly on the lookout for a new dance craze to come along and sweep skiffle and rock ’n’ roll away. In the spring of 1957, calypso was hotly tipped as the next big thing and MM ran a full-page feature entitled ‘Will Calypso Knock the Rock?’ The article centred on the only artist who seemed able to resist the inexorable rise of Elvis Presley – Harry Belafonte, whose album Calypso had vied with Presley’s eponymous debut for the number one position in the Billboard charts throughout 1956.

Teen magazines pitted them against one another, the King of Rock ’n’ Roll vs the Calypso Champion. The subtext of this contest was the growing generation gap. Belafonte was a highly talented twenty-nine-year-old nightclub singer, his smooth delivery popular with fans of swing who had, since the war, been the taste-makers for the music industry. They had driven the mambo mania of 1955 and calypso looked a likely candidate to push rock ’n’ roll back to the juke joints from which it had sprung. Elvis, aged just twenty-one, represented the teenagers and their burgeoning spending power. Among the predominantly album-buying adults, Belafonte won the popularity contest, spending more time at the top of the charts than his rival. However, it was in the crucial singles market that Elvis cleaned up. Belafonte scored a big hit with ‘Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)’, which reached number five in the US and two in the UK, but Presley’s run of hit singles in 1956–7 made him unassailable. The failure of calypso to ride to the rescue seemed to rile Bob Dawbarn, who, looking for someone to take it out on, penned an eviscerating article for Melody Maker entitled ‘Has Trad Jazz Had It?’ (His answer? I bloody well hope so.)

Tommy Steele’s assertion that skiffle was more intellectual than rock ’n’ roll seemed to be borne out by an article that appeared in highbrow Sunday broadsheet the Observer in June 1957 under the title ‘Skiffle Intelligentsia’. ‘Hardly a week goes by without some denigration of skiffle in the musical magazines,’ wrote Hugh Latimer. ‘But skiffle refuses to die. A year ago there were only about twenty groups around London. Now there are nearer 400, with one to ten groups in every English-speaking centre from Glasgow to Cape Town. Sales of guitars have broken all records; shops in Surbiton display them hanging in rows like so many turkeys for Christmas. You can buy washboards, tea-chests, lagerphones, all the paraphernalia of a down-and-outs band. Skiffle has taken by storm the youth clubs and the public schools, and the Army has carried it to Germany. The remarkable thing is that in an age of high-fidelity sound, long players and tape recorders, the young should suddenly decide to make their own music.’

Latimer also proffered evidence that, far from resisting calypso, the skiffle kids were incorporating it into their DIY music along with all the other musical styles that got them dancing. ‘The newer skiffle groups do not distinguish between skiffle and rock ’n’ roll, submerging them all in the same breathless din; if a folksong or a calypso achieves commercial popularity, it goes into the repertory too.’

A month later, The Times suggested that skiffle might represent a new popular art among young people. Their correspondent astutely observed that music hall, the last great popular art to arise in England, had begun with ‘amateur performers singing in modest public houses, conditions which one might, without exaggeration, compare to the sudden appearance of the skiffle singers in the cellarage of coffee bars’.

Fred (later Karl) Dallas attested to the energising effect the skiffle craze was having on the fledgling folk scene. ‘For nearly a decade, my wife and I played and sang folk songs to small, select gatherings. But the “folk” didn’t want to know. Now when my skiffle group plays in the open air at Walton Bridge on Sundays, we can hold crowds of over a hundred with the same songs we’ve been singing all these years.’

The popularity of skiffle as a national phenomenon had been heightened by the arrival in February 1957 of Six-Five Special, a TV pop programme aimed at teenagers, broadcast live by the BBC on Saturday evenings. BBC television had already dabbled in pop music, starting in January 1952 with Hit Parade, on which popular songs of the day were covered by artists such as Petula Clark and Dennis Lotis. This was followed in May 1955 by Off the Record, introduced by Jack Payne, who had served in the Flying Corps during the First World War and led the BBC Dance Band from the 1920s onward. Both shows were aimed at adult audiences, with Payne in particular resisting any move towards skiffle or rock ’n’ roll. When Elvis arrived on the scene, Payne used his Melody Maker column to fulminate against the new movement. ‘Are we to let youth become the sole judge of what constitutes good or bad entertainment? Are we to move towards a world in which the teenagers, dancing hysterically to the tune of the latest Pied Piper, will inflict mob rule on music?’

ITV’s attempt to cater for the teenage audience, Cool for Cats, was a fifteen-minute show hosted by the avuncular Radio Luxembourg DJ Kent Walton, who played popular records while a troupe of dancers interpreted them for viewers. It was broadcast twice weekly at 7.15 p.m., the earliest time slot available for young adults that wasn’t part of children’s programming.

Thanks to a broadcasting regulation known as the ‘Toddler’s Truce’, both BBC TV and ITV left a gap in their schedules every night between 6 and 7 p.m., ostensibly to give parents the opportunity to usher their little ones off to bed. While this may have made sense within the public service ethic upheld by the BBC, for their commercial rivals it meant an hour of lost revenue. And when the independent channels began to struggle financially, the government moved to lift the restriction, much to the annoyance of the BBC, to whom the hour gap represented an opportunity to save costs.

The date agreed for the lifting of the Toddler’s Truce was Saturday 16 February 1957, and the BBC chose to fill the new time slot with a show featuring live music aimed at a teenage audience. The programme was the brainchild of Jack Good, a twenty-five-year-old Oxford graduate who had been president of both the University Debating Society and the Balliol Dramatic Club. Since coming down to London, Good had acted on the West End stage and been part of a comedy duo telling gags between the nude tableaux at the Windmill Theatre in Soho. Finding the commercial pop of the day boring, he fell in love with rock ’n’ roll after witnessing the frenzied dancing of the Rock Around the Clock audiences in a London cinema. By his own admission, he wasn’t overly keen on the music, but he loved the sense of chaotic energy that it generated among the teenagers.

Good wanted to bring some of that energy to the TV screen and approached the BBC with a proposal for a rock ’n’ roll show that would take the audience out of the stalls and place them between the cameras and the artists, giving the viewer the impression that they were watching a teenage party. Realising that they needed to provide something for the growing audience of young adults, the BBC agreed to let Good make six programmes. A number of titles were suggested, among them Start the Night Right, Take It Easy, Don’t Look Now, Hi There and Live It Up, before the producers settled on one that reflected skiffle’s obsession with trains: Six-Five Special.

The paternalistic BBC wouldn’t give Good free rein with the content, insisting that anything aimed at young people should have some educational value. The resulting programme was a mixture of music and magazine, as variety performers shared the screen with boxers and features on outdoor pursuits followed Blue Peter-style demonstrations of how to make a handy item from a cardboard toilet-roll holder and some egg boxes.

Host Pete Murray kicked off the first programme, welcoming viewers aboard the Six-Five Special with some jive talking: ‘We’ve got almost a hundred cats jumping here, some real cool characters to give us the gas, so just get with it and have a ball.’ His co-presenter Jo Douglas, who along with Jack Good also produced the show, followed that by declaring, ‘Well I’m just a square, it seems, but for all the other squares with us, roughly translated, what Peter Murray just said was, we’ve got some lively musicians and personalities mingling with us here, so just relax and catch the mood from us.’

While the screen was filled with young people, it still felt as if the mood was being dictated by the grown-ups. The closest thing to rock ’n’ roll on the bill that first Saturday evening was the King Brothers, a doo-wop-style trio from Essex who had graduated from children’s TV. Crooner Michael Holliday sang some big-band ballads and a sixty-five-year-old Ukrainian-born concert pianist named Leff Pouishnoff played selections from Beethoven and Chopin. Kenny Baker’s jazz band opened and closed the show.

By week three, things had begun to change – Tommy Steele topped the bill. And the following week, Jack Good really got into his stride, producing a show that featured Steele, the Vipers and Big Bill Broonzy. With little competition from the other teenage pop programmes, Six-Five Special was soon drawing a regular 10 million viewers, but Good was hampered by his relatively skimpy budget – just £1,000 per show, much too low to attract big American artists – and the lack of genuine British rock ’n’ rollers. As a result, the music featured on the show tended to be a mixture of pop ballads, trad jazz, skiffle and indigenous rock ’n’ roll, with a sprinkling of classical music and calypso thrown in.

When Tommy Steele first appeared on the show on 2 March 1957, he found himself sharing the bill with a steel band, a classical guitarist and comedy duo Mike and Bernie Winters. Lonnie Donegan was a regular performer, as was Humphrey Lyttelton with his jazz band. Jack Good even managed to squeeze a member of the aristocracy onto the show in the shape of the fourth Earl of Wharncliffe – twenty-one-year-old Alan James Montagu-Stuart-Wortley-Mackenzie was only the drummer for the Johnny Lenniz Group, who appeared on the show on 27 April, yet his title merited a picture in the Radio Times.

Looking to generate excitement with limited resources, the producers took the programme out on the road, presenting live broadcasts from Scotland, Wales, the north, Paris and the NAAFI, a canteen for servicemen, in Plymouth. The most famous of these came on 16 November, when the programme took over the 2 I’s coffee bar in Soho. The Chas McDevitt Skiffle Group with Shirley Douglas were featured, as were the Worried Men Skiffle Group, one of whom, singer Terry Nelhams, would top the charts two years later as Adam Faith.

Such was the lack of space, artists were thrown in to do their piece to camera, only to be ejected back out onto Old Compton Street once they had performed, where television vans blocked the road and the pavement was full of nervous young lads wearing make-up, trying to keep their quiffs intact for their spot on national TV. Terry Dene was prominent among them, but the show also featured Larry Page, the Teenage Rage, who would go on to produce records by the Kinks and the Troggs in the mid-60s; Jim Dale, later an actor in the Carry On movies; and thirteen-year-old Laurie London, who, within six months, would find himself at the top of the US charts with a chirpy version of ‘He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands’ and gain immortality in the opening sentence of Colin MacInnes’s 1959 novel Absolute Beginners.

Despite the conditions, it was by all accounts great TV, but, as all of the Six-Five Special shows were broadcast live – including those filmed at its Lime Grove Studios home in west London – there is no surviving footage to confirm that Gilbert Harding, the fifty-year-old fuddy-duddy broadcaster, no doubt invited by Good to cast his irascible eye over proceedings, was referred to as ‘Daddy-O’ by Wee Willie Harris. The fact that the BBC never taped any episodes of Six-Five Special also deprives us of the sight of Harris, five foot two, red hair, oversize Teddy Boy drape, big bow tie, pink socks and massive crepe-soled creepers, singing his theme tune, ‘Rockin’ at the 2 I’s’, with Mike and Bernie Winters and the King Brothers.

If the chaotic broadcast from the 2 I’s was Jack Good’s finest hour, it was also his swansong. Within two months he’d jumped ship to ITV, leaving the programme in the hands of self-confessed ‘off-duty Mozart fan’ Dennis Main Wilson. Good re-emerged eight months later at the helm of Oh Boy, the rock ’n’ roll show that he’d always wanted to make. Broadcasting in direct competition to Six-Five Special, he set the tone from the first show, which featured the TV debut of Cliff Richard, whose explosive performance of ‘Move It’ propelled him into the charts and caused the Daily Mirror to ask ‘Is This Boy Too Sexy for Television?’ The show was 100 per cent rock ’n’ roll, no skiffle or trad, no comedians goofing around, no films about orienteering or how to apply make-up. The audience were missing too, sat back in the stalls (of the Hackney Empire in London’s East End), although their screams of delight could be heard throughout the broadcast.*

Despite the loss of its founder, Six-Five Special continued to get good viewing figures and its first anniversary was celebrated by a front-page feature in Melody Maker. A month later, a movie spin-off was released, featuring performances from Lonnie Donegan, Dickie Valentine and the ever-present King Brothers, among others. The fact that there were no recognisable rock ’n’ roll acts in the film reflected the problem Six-Five Special faced. Its commercial rival, Oh Boy, had both the budget and the format to attract British rockers. Six-Five Special – never sure if it was a teen pop show or a variety programme – just couldn’t compete for the likes of Cliff Richard.

Instead, while Oh Boy became the nursery for Britain’s would-be rock ’n’ rollers, Six-Five Special embraced skiffle in the form of Stanley Dale’s National Skiffle Contest. The skiffle contest was a phenomenon that harnessed the momentum of the craze, putting the spotlight on amateur players, most of whom were under twenty. The skifflers who enjoyed chart success in the 50s – Donegan, McDevitt, the Vipers – were all born in the 1930s and came out of the jazz clubs. The kids they inspired were almost all born in the 40s and got together in village halls, school gyms and scout huts. Too young to play in pubs and clubs and mostly living out in the provinces, their stage was the skiffle contest.

As many groups were formed from competitive cliques at school, the idea of competing against other skiffle outfits was part of their culture. For fourteen- and fifteen-year-old boys, skiffle had an even greater attraction than football. Sure, being in the school team might impress your mates, but playing skiffle attracted girls, who, more than anything, wanted to jive to up-tempo music (often with each other, much to the chagrin of local lads).

The heats of the skiffle contest were held at the local cinema or variety theatre, with winners decided by the reaction of the crowd. Victory in the local heats would send groups through to semi-finals against outfits from around the country and success could bring national recognition – in November 1957, the BBC broadcast the finals of the World Skiffle Championship on prime-time TV as part of the popular ballroom dancing show Come Dancing. The Daily Herald newspaper offered a prize of £175 to the winners of national weekly skiffle contests held during the summer of 1957 at Butlin’s holiday camps across the country, later claiming that around eight hundred groups had taken part.

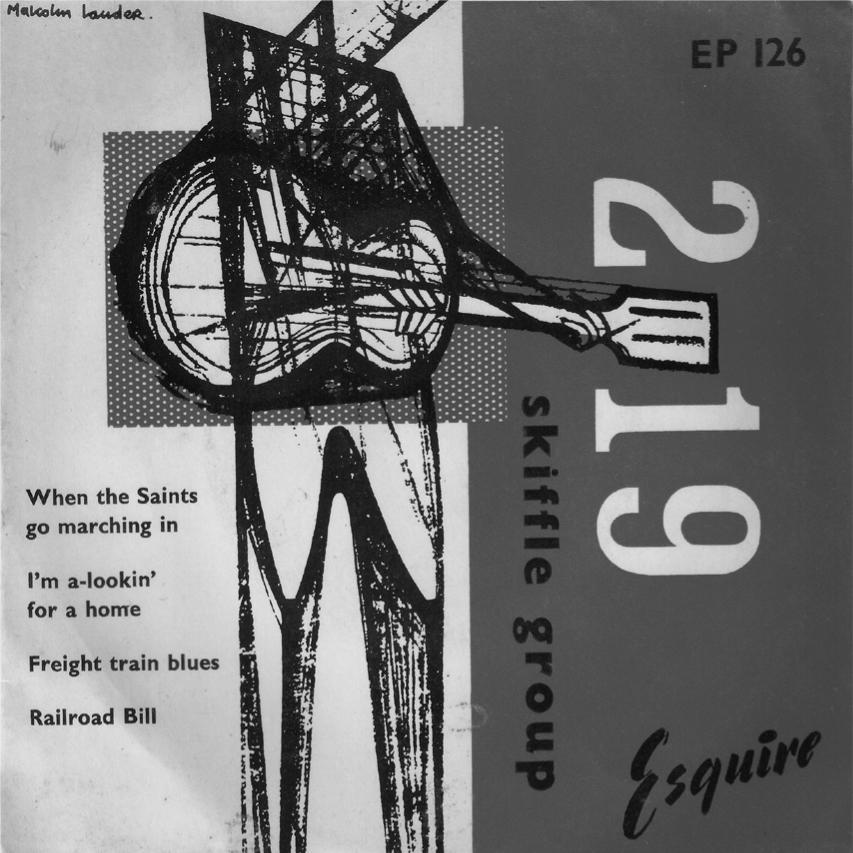

Whit Monday, the public holiday that heralds the beginning of the summer season, had traditionally been the date on which the Round Table in Bury St Edmunds, a sleepy town in rural Suffolk, held their charity fete. In 1957, it fell on 10 June and they decided to hold a one-day national skiffle contest in conjunction with the International Jazz Club. Groups came from as far afield as Swansea and Glasgow, one determined bunch – the Skiffle Cats from Paddington – walking the seventy-five miles from London to Bury St Edmunds. Once the non-skifflers had been weeded out from the hundreds of groups that tried to enter, forty-four were chosen to participate. In the event, only thirty-four turned up, the outdoor venue and the classic British Bank Holiday downpour discouraging the more faint-hearted. Each group was given six minutes to perform two songs before the judging panel of Johnny Duncan, blues and skiffle authority Paul Oliver and jazz critic Graham Boatfield. There were prizes to be won and the promise that winners would be recorded by Esquire Records.

In an article for Jazz Journal, Boatfield described the groups as predominantly acoustic, with an average of three guitarists each. If he detected a unifying characteristic among the youths who gathered under the trees, trying to keep their instruments dry on that damp Bank Holiday, it was one of class. ‘If one must categorise skiffle, it seems on this showing to be a very thriving music of young workers from the towns.’

Boatfield detected the ‘pernicious influence’ of Lonnie Donegan on the material chosen by performers, with some Elvis Presley thrown in for good measure. He even found some ‘deep diggers looking for their own native folk music’. Sixty years later, his description of the crowd will resonate with anyone who has ever attended an English charity fete on a wet weekend: ‘A surprisingly large crowd stood in the steady rain watching the performers, gently exuding a sort of damp unconcern and that inspired melancholy with which the Anglo-Saxons take their pleasures.’ The fact that the MC was a young clergyman seals the scene.

Boatfield’s main complaint was the paucity of original material. Again and again the same songs were thrashed out in the rain: ‘Wabash Cannonball’, ‘Worried Man’, ‘Cumberland Gap’ and the ubiquitous ‘Don’t You Rock Me Daddy-O’. ‘After the tenth repetition of any opus one’s spirits flagged and it was refreshing to hear a few others which, if not original, at least showed some acquaintance with a wider field.’ The youngest musician was just twelve years old.

Each group was given marks for style, originality, ease of performance and musical ability. Independently from these scores, points were awarded for original compositions, of which more than a dozen were performed. The eventual winners – ‘not difficult to spot, but it took a long time to get there’, lamented Boatfield – were the 2.19 Skiffle Group from Gillingham, Kent, who doubtless impressed the old jazz journalist by taking their name from Louis Armstrong’s ‘2.19 Blues’. Second came the Station Skiffle Group from Fulham, and in third place were the winners of the All Scottish Skiffle Contest, the Delta Skiffle Group.

Yet as the damp crowds dispersed at the end of a long day’s skiffling, spirits among some of the victors were even damper. Having made a 750-mile round trip from Glasgow – in a Britain that had yet to build any motorways – the Deltas were angry that, despite the advert for the contest promising cups and cash prizes, they were given just £5 and no trophy for coming third. Promised a gig in London to tie in with their Esquire recording session, all they received was £1 between them and their train fare home to Glasgow. And although an album featuring all three bands duly appeared on Esquire Records, in hindsight the impartiality of the organisers is put into question by the fact that, before the contest was held, the 2.19 Skiffle Group had already released two EPs on the Esquire label.

The skiffle contests were run almost entirely on enthusiasm, and it wasn’t long before someone hit on a way to make money from the phenomenon. Stanley Dale, a middle-aged variety promoter and manager of the Vipers, shrewdly noted that, if a contest was judged on audience reaction alone, then competing groups would be likely to bring as many people as possible to the gig, in the hope of getting the loudest applause. In August 1957, Dale sent the Vipers out as headliners on a traditional variety tour billed as ‘The Great National Skiffle Contest’. Just before the interval, following the usual selection of variety acts, four skiffle bands would compete for a place in the final at the end of the week-long residency, the winners receiving cash prizes and the promise of an appearance in a big championship show ‘sometime in 1958’. When the Vipers closed the evening with their three guitars, washboard and bass, they were more or less guaranteed a packed house of enthusiastic skiffle fans – the most ardent of whom would all come back on Saturday for the ‘finals’.

Despite the obviously exploitative nature of the whole enterprise, the popularity of playing skiffle in front of an audience was so attractive to young groups that Dale was able to run the tour all the way to the spring of 1958. During the one-week stand at the Finsbury Park Empire, fifty amateur skiffle groups performed, with twenty-eight others being invited to participate in later local contests. In his most audacious move, Dale booked Barking Odeon for what Fraser White, writing in the Weekly Sporting Review & Show Business, described as ‘the cheapest Sunday concert that has ever been known in London’ – cheap for the promoter, that is. Such was the popularity of skiffle in the working-class suburbs of the outer East End that Dale – dispensing with the entire variety bill for this one show, and retaining only the contest’s MC, Jim Dale (no relation) – was able to find four dozen eager skiffle groups to fill the stage. White was beside himself with admiration. ‘On the bill was only one paid artist … Jim Dale. The rest of the bill, in both houses, was made up of 48 unpaid skiffle groups who clamoured at the door to make money for Stanley Dale. All the know-alls said he’s nuts. He’ll lose a packet. But they were wrong. Dale gained a packet – a packet of five hundred crisp one-pound notes, which was the clear profit he carried away from one night at Barking!’

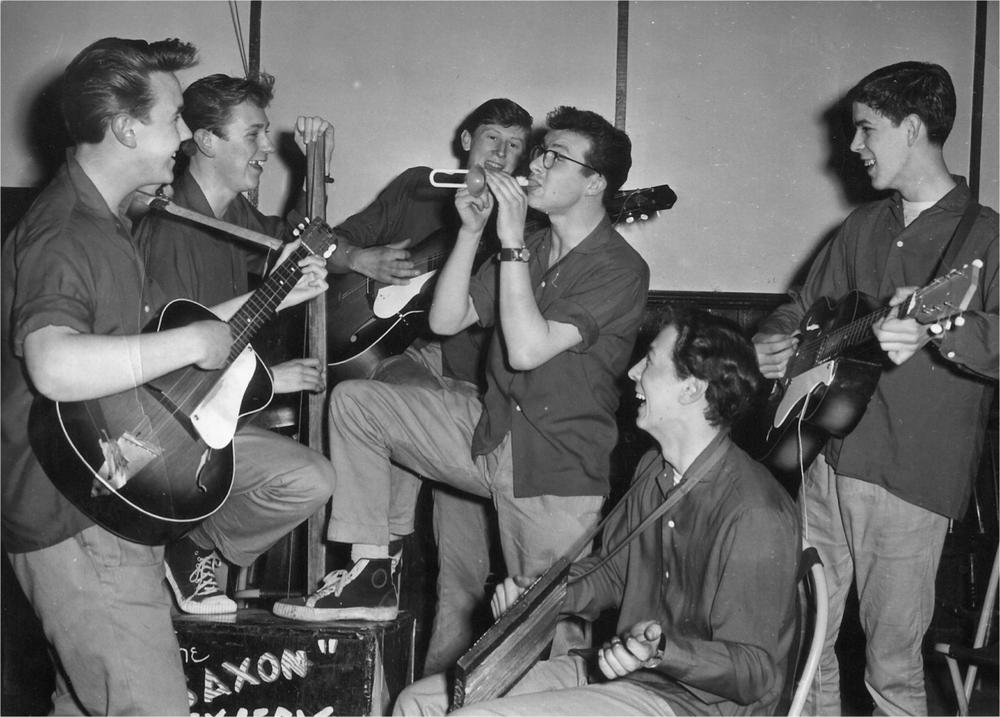

The contest was won by the Saxons, who, in keeping with what seemed to be a trend among amateur skiffle bands, took their name from an aspect of local history, in their case the founding of Barking Abbey in ad 666 by Erkenwald, the Saxon bishop of London. That a local band should win might seem obvious, given that they could rely on supporters to turn up on the night, but some background to their brief career offers an insight into what was a flourishing amateur skiffle scene.

The Saxons were comprised of Keith Jacks, eighteen years old, on banjo and guitar; Denis McBride, seventeen, on banjo; Michael Platt, sixteen, on guitar; David Bruce, sixteen, guitar; Alan Taylor, seventeen, on washboard; and Thomas Clatworthy, eighteen, on tub bass. They were all members of the youth club that met at St Thomas’s Church on the Becontree Estate, the largest housing project in Europe, constructed between the two world wars. The local paper described them as by far the best group in the competition, a view supported by the fact that they had won first place in a similar contest held at the Gaumont on Dagenham Heathway just a week before, first place in a contest in Holborn, and had triumphed in the Southern England finals of the World Skiffle Contest that had aired on BBC TV’s Come Dancing. A report in the local paper noted that these busy boys were also making frequent appearances at the Skiffle Cellar in Soho.

By February 1958, Stanley Dale’s National Skiffle Contest had turned into Groundhog Day. The same lame comedians telling the same tired jokes, dozens of skiffle bands thrashing out their own frenzied version of ‘Don’t You Rock Me Daddy-O’, and the Vipers themselves locked into a straitjacket of a seventeen-minute set, twice a night, every night. And the tour just kept on rolling, with no real end in sight. Every time they pulled in to a new town, a crowd of local skifflers appeared, eager for their moment in the spotlight.

Dale had one final trick up his sleeve. In January, he announced that the final rounds of his National Skiffle Contest would be broadcast live on TV. The first heat took place on Six-Five Special on Saturday 1 February, with viewers being encouraged to send in postcards in support of the contesting groups. By the time that the Saxons appeared on the programme on 26 April 1958, Six-Five Special had given up any pretence of being a rock ’n’ roll show. The main act that Saturday was Ronnie Aldrich and the Squadronaires, a big band of former RAF musicians. Mick Mulligan’s trad jazz band had a spot, as did the Lana Sisters, a vocal trio that included one Mary O’Brien, later to find fame as Dusty Springfield. The only teenage music on the show was provided by the skiffle contest.

The Saxons rehearse for their Six-Five Special appearance at St Thomas Youth Club, Dagenham, July 1956

The Saxons defeated the Sinners from Newcastle and went through to the second of three semi-finals on 19 July, where the middle-aged, middle-of-the-road Ted Heath Band was top of the bill. The boys from Barking performed their version of ‘I’m Satisfied’, which had been the B side of the Chas McDevitt Skiffle Group’s third single, ‘Greenback Dollar’. One of their opponents that evening was the Station Skiffle Group from west London, who had come second at the wet Whit Monday contest in Bury St Edmunds a year before. Both they and the Moonshiners from Sheffield performed songs from Lonnie Donegan’s repertoire, ‘Tom Dooley’ and ‘The Grand Coulee Dam’ respectively. Again the Saxons were victorious and made it through to the final.

Broadcast on 23 August, almost a year to the day after Stanley Dale had first sent the Vipers out on the road with the National Skiffle Contest, the finals were won by the Woodlanders from Plymouth, with the Saxons coming a close second. Derek Mason, who played washboard for the Station Skiffle Group, later commented that ‘we felt that was an injustice as [the Saxons] were by far the better of the three finalists’.

The skiffle contests blooded a new generation of amateur musicians who were able to get a shot at national recognition without having to surrender their personalities to the demands of music business impresarios such as Larry Parnes who would single out a boy, change his name and hairstyle, provide his clothes and tell him what to say. The skiffle groups were bands of brothers, self-realised and answerable only to one another, a trait that would give these young teens the confidence to write their own songs and take on the world in the decade that followed.

* Oh Boy was Jack Good’s masterpiece and its influence can be seen in the production values of 60s shows like Ready, Steady, Go! and Top of the Pops. Good went on to work in America, where he created Shindig for the ABC network in 1964.