‘Skiffle on the Skids’, proclaimed the front page of Melody Maker on 17 May 1958, atop a report on the declining fortunes of artists who, just a few months before, had been filling theatres across the land. Skiffle had swept all before it during 1957, with the Vipers, Johnny Duncan and Chas McDevitt all scoring several hits. Head and shoulders above the competition stood Lonnie Donegan, with five Top Ten singles, two of which had reached number one. But as 1958 progressed, only Donegan continued to have hits, and when, in October, Saturday Skiffle Club was relaunched on the BBC Light Programme as the more pop-oriented Saturday Club, it became clear that the skiffle boom had passed its peak. Yet just as the British were beginning to tire of hearing American folk songs in their charts, a folk song reached number one in the US.

Originally performing as the Calypsonians, the Kingston Trio took their name from Kingston, Jamaica, and hoped to hitch a ride to fame on the calypso craze that was gathering momentum in 1957. Gaining an audience on the Californian folk circuit, they released an album of mostly traditional songs in June 1958. Their clean-cut image and college-boy harmonies made them easy on the ear and, unlike other American folk singers of the late 50s, they avoided any overtly political references in their material. Popular with DJs, their wholesome version of ‘Tom Dooley’ reached the top of the Billboard charts in November.

The song tells of the murder of Laura Foster in Wilkes County, North Carolina, in 1866 by former Confederate soldier Tom Dula, for which crime he was tried and hanged. The version recorded by the Kingston Trio was first collected from an old-time Appalachian banjo player named Frank Proffitt, of Pick Britches Valley, North Carolina. Born in 1913, he learned the song from his immediate family, some of whom had known both killer and victim. Donegan, perhaps sensing his chance to get revenge on those American artists who had recorded copycat versions of ‘Rock Island Line’, swiftly released his own take on ‘Tom Dooley’, which reached number three in the UK charts in December 1958, topping the efforts of the Kingston Trio, who only managed to get to number five.

The contrast between their arrangements of the song underscores the differing manner in which the musicians of the American folk revival and British skiffle boom handled roots material. Where the Kingston Trio are sombre, as if playing at Laura Foster’s funeral, Donegan employs a relentless rhythm, yelping and growling the lyrics, constantly pushing the pace of the song. Both versions have their merits, but Donegan’s is closer in style and delivery to that of fiddle and guitar duo Grayson and Whitter, who made the first recording of the song for Victor in 1929.

Despite the transatlantic success of ‘Rock Island Line’ and ‘Freight Train’, skiffle never took hold in the US. There were those around the fringes of the music industry who used the term, but their efforts bore little resemblance to what was happening in the UK. In April 1957, crooner Steve Lawrence released a single called ‘Don’t Wait for Summer’, backed by Dick Jacobs and His Skiffle Band. Jacobs was a thirty-nine-year-old New York A & R man who had introduced string arrangements to Buddy Holly’s recordings. The sleeve of his 1957 EP Dig That Skiffle features washboard, banjo, bongos and guitar, but a cursory listen reveals that Jacobs had never heard the Vipers in full flight. The title track comprises a male chorus simply repeating the words ‘Dig that skiffle’ over a hokey electric guitar phrase, while the rest of the tracks are schmaltzy easy listening. You don’t rock me, daddy-o.

Milt Okun was another music industry back-room operator, a successful arranger and producer of folk artists in the 50s and 60s. He was the moving force behind the Skifflers, who sounded more like the Weavers than anything a British teenager might recognise as skiffle. American jazz archive label Riverside sought to cash in on the craze by reissuing some Roy Palmer recordings from 1931 that featured the word ‘skiffle’ prominently on the sleeve. However, this was Chicago skiffle, barrelhouse piano instrumentals of the kind played by Dan Burley and His Skiffle Boys.

The water was further muddied when, in 1957, Folkways issued an album entitled American Skiffle Bands, which featured archive recordings by the Memphis Jug Band, Cannon’s Jug Stompers and the Mobile Strugglers. It was a good enough collection of music that had been popular in the 1930s, but the fact remained that, before Lonnie Donegan hit the Billboard charts, no one in America would have referred to this music collectively as skiffle.

Which is not to say that some American artists weren’t influenced by what was going on in the UK. In his autobiography, The Mayor of MacDougal Street, folk singer Dave Van Ronk reveals that the first record he made was inspired by Donegan’s success with ‘Rock Island Line’. Released on a small-time New York label named Lyrichord, Skiffle in Stereo featured a group of young jazz fans, including Van Ronk and Samuel Charters, who would go on to become one of the great authorities on African American roots music. Despite the title, this was more of a jug band record, a fact recognised by the name the group chose to appear under – the Orange Blossom Jug Five.

American youth may not have been bitten by the skiffle bug in quite the same way as their British contemporaries, but some US teens were becoming interested in the kind of material that skifflers were drawing on. Greenwich Village was the epicentre of this scene on the east coast and Washington Square was its Ground Zero, a place where young amateur folk singers and players could gather freely at weekends to perfect their skills among supportive souls.

The opening of the Folklore Center on MacDougal Street in February 1957 provided a focal point for teenagers hungry to learn more about old-time music. Proprietor Izzy Young offered advice and information, as well as organising concerts. By the late 50s, the old guard of American folk, artists who had promoted music with a left-wing consciousness during the 30s and 40s, were beginning to fade away. In their place rose a new generation of musicians who, like the skifflers in the UK, were drawn to the old-time music. The New Lost City Ramblers – Tom Paley, John Cohen and Mike Seeger, brother of Peggy and Pete – were multi-instrumentalists who specialised in banjo, fiddle and guitar. The same age as Ken Colyer, Chris Barber and Lonnie Donegan, they shared the anti-commercial instincts of their British counterparts.

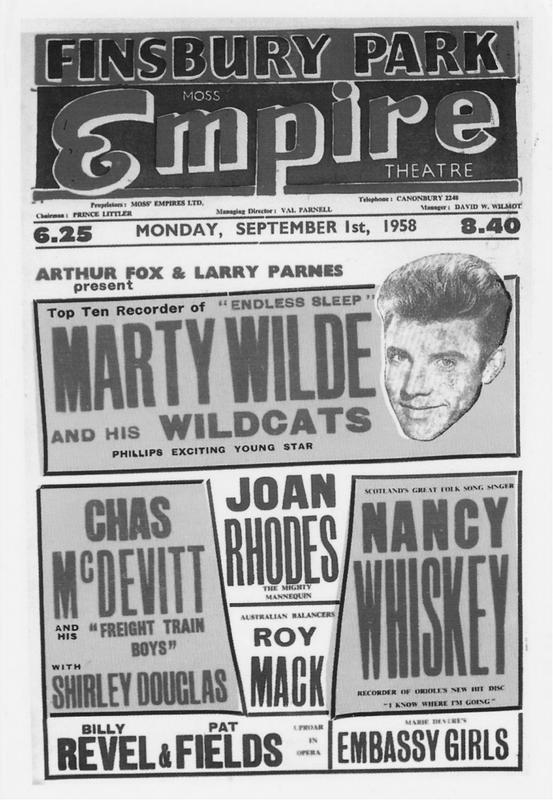

Skiffle is pushed down the bill by British teen stars

In the sleeve notes to their eponymous debut album, released on Folkways in 1958, Tom Paley outlined the group’s philosophy. ‘Our principal reasons for playing together are a liking for the sound of old-timey string bands, perhaps best exemplified by the North Carolina Ramblers and Gid Tanner’s Skillet Lickers, and a feeling that this sound has just about disappeared from the current folk scene. There are many fine individual performers about and quite a number of good groups too, but the groups have virtually all followed either the Bluegrass trend of Scruggs & Flatt and Bill Monroe or the slick, modernized, carefully arranged approach of the Weavers and the Tarriers. We have no objections to either of these schools, but the older style seems deserving of resurrection.’

Like Ken Colyer, the members of the New Lost City Ramblers individually sought out the ageing artists who still played the music that they loved, although unlike Colyer they didn’t have to cross an ocean to do so. Old-time players like Doc Watson, Roscoe Holcomb and Clarence Ashley were still active in their Appalachian communities, and in the years that followed, Paley, Cohen and Seeger would be instrumental in bringing these artists to national prominence. But whereas skiffle’s back-to-basics ethic had inspired hundreds of thousands of British kids to pick up a guitar, the example of the New Lost City Ramblers went largely unheeded. In the first year that their album was on sale, it sold fewer than 350 copies. The American folk revival would instead be inspired by the slick, modernised and carefully arranged Kingston Trio. By the end of 1959, they had four albums in the Billboard Top Ten, a feat never equalled before or since. Four years after Lonnie Donegan had charted with an old Lead Belly song, American musicians had begun to find similar success in mining their own past for hits.

As more folk-style songs entered the American charts in the wake of the Kingston Trio’s success, Donegan sensed a new source of material. After releasing his take on Skeets McDonald’s regional hillbilly hit ‘Fort Worth Jail’, Lonnie scored his biggest hit for two years, reaching number two with ‘The Battle of New Orleans’, which Johnny Horton had recently taken to the top of the American charts.

Peter Sellers would mercilessly satirise this switch from singing Lead Belly material to recording US hits in a sketch on his best-selling album Songs for Swinging Sellers. Purporting to be an interview between a clipped BBC type and the skiffle star ‘Lenny Goonigan’, Sellers – doing both voices – brilliantly captures Donegan’s whiny voice and notoriously defensive nature. When the BBC type asks where he discovered his current hit single, Goonigan replies, ‘It was an obscure folk song hidden at the top of the American hit parade.’ Donegan was not amused, especially when it turned out that Wally Whyton of the Vipers had a hand in the script.

When Johnny Horton scored another hit single with an old country number called ‘Sal’s Got a Sugar Lip’, Donegan swiftly followed suit. The song was originally performed by the Carlisle Brothers, Cliff and Bill, two Kentucky singers whose material often relied on sexual innuendo. Their version of the song, recorded in the 1930s, was entitled ‘Sal’s Got a Meatskin’, which, the lyric informs us, she keeps ‘hid away’ – her hymen, in other words. The audience at the Royal Aquarium, Great Yarmouth, were doubtless unaware of this fact when Donegan performed the song for them during his 1959 summer season there, but the live recording of ‘Sal’s Got a Sugar Lip’ made during the run got to number thirteen in the UK charts that September.

Donegan’s final single of the year was another of the Kingston Trio’s run of hits, this time from the pen of their most favoured songwriter, Jane Bowers. ‘San Miguel’ found Lonnie crooning in a cod-Spanish accent, rolling his ‘r’’s for all he was worth while mispronouncing the ‘Meeg-el’ of the title as ‘Mig-well’, making it sound like a village in Bedfordshire rather than some distant Mexican pueblo.

‘San Miguel’ was the last of Donegan’s singles to be credited to his skiffle group. Chris Barber’s old banjo player was now a bona fide star with his own weekly TV show. Putting On the Donegan made its debut in 1959 as a half-hour variety show screened in a weekly prime-time 8 p.m. spot. The man who had been horrified to discover his blues hero, Lonnie Johnson, performing in a white tuxedo when he shared a stage with him at the Festival Hall in 1952 was now seen in tux and bow tie every Friday night on commercial television.

In truth, skiffle had been mutating for some time. One thread of this process can be discerned in the pages of a fanzine produced by a fifteen-year-old working-class Londoner. Michael Moorcock would go on to become one of Britain’s greatest science-fiction writers, but his first publications were fanzines that he typed, illustrated, duplicated and distributed himself. One was entitled Jazz Fan, ‘an irregular publication circulated mainly in fandom but chucked at anyone who is interested. Articles or art work connected with jazz, skiffle and r&r welcomed.’

Born in 1939, Moorcock was a regular face on the Soho teen scene. Legend has it that it was he and fledgling jazz drummer Charlie Watts who first suggested to Tommy Steele that he should try his luck at the 2 I’s. Available by post from the Moorcock family home in Norbury, SW16, and distributed free at gigs, Jazz Fan number 7, produced at the height of the skiffle boom in May 1957, contained a couple of pages reviewing the newest skiffle releases. The following issue found Moorcock declaring the Cotton Pickers – regulars on the West End circuit and featuring Tommy Steele’s old mucker Mike Pratt – to be performing ‘the most authentic interpretation of American folk-songs ever to appear under the name SKIFFLE’.

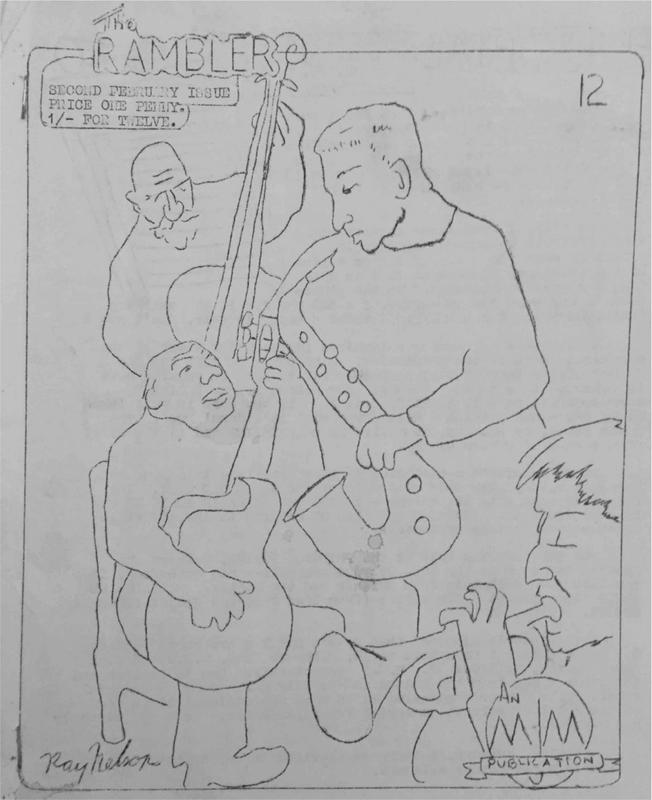

But by February 1958, the magazine had changed its name to The Rambler and, although the cover illustration depicted a jazz quartet, the focus of its content had moved towards traditional folk music. An article written by Sandy Paton, a twenty-eight-year-old folk singer visiting from the US, bemoans the fact that America has no equivalent to the Soho coffee bar where teenagers could nurse a cappuccino all night long while listening to live guitar music, maybe even get up and play themselves. Paton also complains that skifflers don’t know any traditional British folk songs. By March 1958, The Rambler had become a fanzine about the burgeoning London folk scene, with an enthusiastic young Moorcock encouraging his readers to hear folk music at former skiffle strongholds such as the Breadbasket, the Round House and the Princess Louise.

The Rambler fanzine, February 1958

Ewan MacColl had been intermittently hosting events at the Theatre Royal in Stratford in east London under the banner of ‘Ballads and Blues’ since 1954, latterly billing the event as ‘folk music, jazz, work songs and skiffle’. In late 1957, he moved to the Princess Louise, where, on 24 November, he opened one of the first folk clubs in Britain. Four months later, Eric Winter described the pub as ‘overflowing with refugees from the skiffle craze … indistinguishable in dress or appearance from a Tommy Steele fan club, drinking in and applauding large instalments of the Child Ballad Collection’.

The club retained some of skiffle’s infectious enthusiasm. ‘There are generally about thirty bods with guitars and when they remember, performers shout out the chord sequences and everyone joins in,’ wrote MacColl in a letter to Peggy Seeger in 1957.

While MacColl was willing to accommodate the inclusive spirit of skiffle, which insisted that anyone could pick up a guitar and play, he was less tolerant of the skifflers’ tendency to sing in an Americanised accent. MacColl saw the commercial onslaught of American culture as a threat to the indigenous folk music of the UK. He was not alone in this concern – it was even shared by some folklorists in the US – but few went as far as he did to counter it. As early as March 1958, he was arguing that singers who performed at the Ballads and Blues Club should sing material from their own culture. English singers should sing English songs, Irish singers Irish songs, and so on. Only American singers were allowed to sing the blues. Peggy Seeger explains how the policy came about:

‘I think it was Long John Baldry singing “Rock Island Line” that brought matters to a head. His accent just cracked me up. I was laughing so hard they had to take me out of the room. The next week I was hauled before the club’s Audience Committee, who took me to task saying no matter how funny you think it is, you don’t start laughing in the middle of a performance. I said what was so funny was that Lead Belly used to visit our house, I’d listened to Lead Belly from the time I was little, so I know what that song should sound like. We had a French guy on the committee and he said, “Well, in that case I would be very grateful if you did not sing any French songs, Peggy.” Then another member of the committee said, “Well, that guy who came a while ago” – referring to Theo Bikel – “who sings Russian songs? I speak Russian and his Russian accent is dreadful.”

‘Bert Lloyd sang Australian songs but he’d been down there and he could mimic an Australian accent very well. Ewan could do a Scots accent beautifully, but when someone said to me that I shouldn’t sing French songs, I kind of got a bit irritated by that and I turned to Ewan and said, “Well, I wish you’d stop singing ‘Sam Bass was born in Indiana, it was his native home’ with a fake American accent,” and we should’ve tumbled around laughing because it was so funny.

‘Instead, we decided that on stage, only on stage, you sang in a language you understood and a language the vowels of which you used in your speech. This immediately hauled Bert back to Australian and English, Ewan to Scots and English. He had to stop singing Irish songs and I was to stop singing all those songs that Pete [Seeger] sings, which I had been singing for a long time, and concentrate on American songs mostly from the east coast. I could never sing Woody Guthrie because I didn’t have that Oklahoma accent.’

This prescriptive approach was full of glaring contradictions. How could MacColl, an internationalist by conviction, impose a nationalist policy on those who came to sing at his club? And if there were to be restrictions based on regional and national identity, then why not also recognise gender, class and religion? ‘The Policy’ did have the effect of sending young singers off to explore their own cultural heritage, but was it really necessary for MacColl and Seeger – two great artists who spent their lives challenging authority – to set themselves up as the Folk Police?

Across the UK, young people who had been inspired to play American folk music by Lonnie Donegan were starting to explore their own tradition. Norma Waterson, born in 1939, had been taught to play guitar by her first husband and formed a skiffle group with brother Mike, sister Lal and banjo player Pete Ogley. Called the Mariners, they played anywhere they could in their native Hull: coffee bars, street corners, pubs and at the Albion Jazz Club. On a trip to London, Norma and her husband, a guitarist in a Dixieland jazz band, visited the Studio 51 club in Soho, where Ken Colyer held court with his Jazzmen. Norma was surprised to find traditional folk musicians in a jazz club: ‘In the interval, we thought it would be skiffle, but this man and woman got up – the woman looked like my granny with jet-black hair. The guy played the fiddle and she played the banjo. She began singing and I was lost. She sang “She Moves Through the Fair”. It was Margaret Barry and Michael Gorman.’

At the instigation of their banjo player, the Mariners had been playing mostly American folk music. ‘Pete Ogley used to play a long-neck banjo and all the songs in our set were Pete Seeger songs, so when Pete O’s wife told him he couldn’t play with us any more, the whole set was gone and we were left with an English-only repertoire. We were lucky in that the local library had a good music section and we went and had a look, and there was one of Frank Kidson’s books [of English folk songs collected in the 1890s] and we took it out and thought, “This is really what we want.”’

Renaming themselves the Folksons and making a point of singing in their own accents, they opened Hull’s first folk club, the Folk Union One, in the city’s Baker Street Dance Hall. They soon made contact with a group of young men in Liverpool who were also making the transition from skiffle to folk.

On a visit to Paris, Alan Sytner had been highly impressed with the jazz clubs on the Left Bank of the Seine, especially one built into an underground cave, Le Caveau de la Huchette. Returning home to Liverpool, he began searching for a venue with a similar ambience, opening the Cavern Club in August 1956. The first night featured music from the Merseysippi Jazz Band and the Coney Island Skiffle Group, among others. The Cavern was a jazz club, but the popularity of skiffle meant that Sytner was soon running a whole night dedicated to this teenage music.

Among the popular skiffle acts at the Cavern was the Gin Mill Skiffle Group, comprising friends who had met at teacher training college. Tony Davis and Mick Groves began their career playing during the intervals in the Merseysippi Jazz Band’s set, but soon drew their own devoted audience. They were introduced to English folk music by Redd Sullivan, at that time a regular singer with John Hasted’s skiffle group at the Forty-four Club in Soho.

Redd Sullivan (centre) sings with the John Hasted Skiffle Group, 1956. Hasted on banjo (right)

‘Redd was a stoker on the Elder Dempster Line and came into Liverpool occasionally with the boat, and that’s how he came across us,’ recalls Mick Groves. ‘It was Redd that actually said to Tony and I, “What are you two English schoolteachers doing singing these American things? Nothing wrong with them but why are you doing that? Why don’t you sing your own songs from here, from Liverpool?” We said, “What do you mean?” And he said, “Sea shanties, songs about the sea,” and we just went on from there to start looking at sea shanties, which became part of our early repertoire.

‘The local members of the English Folk Dance and Song Society used to meet every week in the Friends’ Meeting House, right across the street from the Empire. Tony and I went along, and they used to sit around a baize table, the old men in their suits and the women in their best coats and hats, and sing traditional folk songs from a book. Sullivan arrived for a few days and we said, “It’s this folk thing tonight, do you want to come along and talk to them about the songs that you do?” So he came, and they started by doing their usual singing rounds and then welcomed him, and he said his piece and sang a couple of music-hall songs and shanties. When he finished they all applauded and this woman said, “I don’t know what we are doing here trying to sing folk songs when surely we have to listen to people who have lived it.”’

Inspired by the new material they discovered at Sullivan’s suggestion, Tony and Mick opened a folk club in a basement below Sampson and Barlow’s restaurant on London Road in Liverpool city centre in September 1958.

Leon Rosselson was a member of one of several skiffle groups that had splintered off from the left-wing London Youth Choir. The Southerners eschewed the skiffle songs that they heard on the radio, preferring material that reflected their political beliefs, such as ‘Union Miners Stand Together’, Joe Glazer’s ‘Put My Name Down’ and anything by Woody Guthrie. Otherwise, they followed the classic skiffle group path, entering a national competition – albeit in their case one organised by the Daily Worker – and auditioning unsuccessfully for Saturday Skiffle Club. They were ideally placed to participate in the Aldermaston Marches, having already performed at numerous peace rallies with the London Youth Choir.

Rosselson has long maintained that skiffle plus CND led to an outpouring of new topical songs at the end of the 1950s, long before the American protest song boom began. ‘For a short time, skiffle, musically primitive as it was, broke the power of the commercial music industry, which didn’t happen with Elvis Presley, Bill Haley and all that,’ he recalls. ‘It was, as they say, empowering, turning consumers into participants, and indirectly, I think, leading to the new song boom. If you could make your own music, you could write your own songs.’

The skiffle boom may have been over, but for a generation of youngsters empowered by learning to play guitar, their adventure was just beginning.