In 1927 Little Rock witnessed two seemingly contradictory events, occurring only a few miles apart. Together, they help illustrate how, even thirty years later, the city could be a place of both lofty aspirations and deep-seated intolerance. The paradox was, in fact, nothing new: Little Rock was also where, in 1889, Frederick Douglass was welcomed by the state legislature, but turned away by a local restaurant.

In May 1927 a thirty-five-year-old black man named John Carter, the married father of five, fled into the woods after supposedly assaulting a white woman and her daughter on the road to Hot Springs. A search party tracked him down, and before long a lynch mob had gathered around him. The men tied together a rope and chain, placing one end atop a telephone pole and the other around Carter’s neck before forcing him to climb onto the hood of a Ford roadster. “Start praying, nigger, because you are getting ready to go!” someone shouted. Strictly as a matter of visual dramatics, this lynching was a bust; when the car pulled away, Carter dangled only five feet off the ground. But it sufficed. He hung there for two minutes—just long enough to die. Then fifty men riddled him with some two hundred bullets.

The corpse was tied to a rear bumper, and a procession of thirty or forty cars, filled with howling men and boys, made its way into Little Rock, passing undisturbed by the police station and courthouse en route. After driving around for an hour, the mob placed the body on the trolley tracks at West 9th Street and Broadway, in the heart of the black part of town, then doused it with gasoline. Four or five thousand people, including women with babies, converged on the scene, and for the next three hours or so, they celebrated around the blaze. Whenever the fire died down, more gasoline, along with boxes, doors, windows, and furniture, some of it lifted from nearby black homes and a black church, brought it back to life. The police stood by; the mayor showed up only after Carter was but a charred crust. His bones became prized souvenirs.

Little Rock’s blacks, who had huddled in terror as the events unfolded, slowly emerged from their homes and businesses as the furor died down. (Those who had stuck around, that is: Elizabeth’s grandfather had hidden his children under a bed, then spirited them via the Rock Island Line to Forrest City, ninety-five miles to the east.) Afterward, from the relative safety of the North, the black press recapitulated what had happened. To the crowd, the Chicago Defender related, Carter’s culpability hadn’t really mattered: “All they wanted was to see human blood—hear human cries for mercy—smell human flesh as it burned itself out. They wanted their children to grow up with the memory of a human being hanging from a tree, his head almost shot away, blood streaming from a hundred holes in his body!” When it was all over, the Defender reporter wrote, “the crowd, tired from its exertions, hungry but happy, dispersed. Some went back to their businesses, some returned to their pulpits, some to finish their housework, and the children to their classrooms. It was a perfectly gorgeous affair, and everyone was happy. That is a picture of Arkansas.”1

Over the next few weeks, the Missouri Pacific sold record numbers of tickets to blacks fleeing Little Rock. The lynching, the city’s first in thirty-six years, horrified respectable whites—“a Saturnalia of savagery,” the Arkansas Gazette called it—but only to a point: no one involved was ever prosecuted, nor was any official ever removed from office (though both the Defender and another leading black weekly, the Pittsburgh Courier, were soon banned from Little Rock because, in the words of the local censorship board, “they agitated the state of mind of the colored populace of the city”). In the next thirty years nothing remotely similar had happened. But how many eyewitnesses, including all those children who’d either looked on or cowered in corners, remained part of Little Rock, circa 1957? How quickly or completely could such hatred, and fear, ever dissipate? How much, in fact, would it only have been stoked as blacks, however tentatively, began pressing for their rights, including the right to have their children attend the same schools as whites?

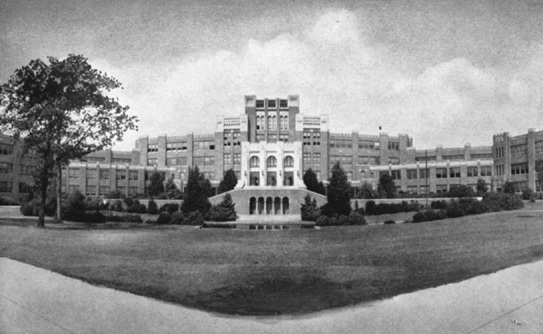

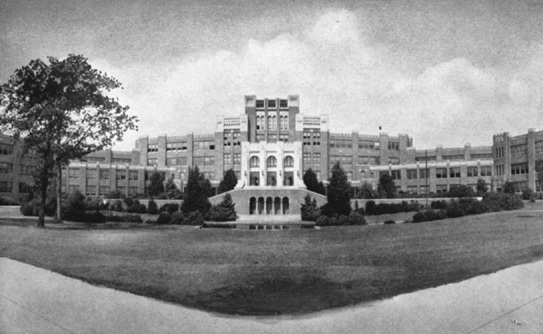

The glow from the funeral pyre that night surely illuminated the glorious new home for Little Rock High School—the “Central” part came much later—that was rising only a few miles away, on Park between 14th and 16th Streets. A Gothic structure of buff-colored brick enveloping two full city blocks, it was monumental, stately, self-confident—emanating what the Arkansas Democrat called “an almost ancient cathedral permanence.” Clearly, it was too big and grandiose for its present purposes, but the city fathers were thinking epic thoughts: one day and soon, it all but shouted, progressive, forward-thinking Little Rock would grow into it. In a region so wedded to, and crippled by, its past, here was a building that looked resolutely forward. “Helping to Make Little Rock Famous,” the Little Rock Gas and Fuel Company said of the school in an advertisement that ran when the building formally opened that November. And this turned out to be prophetic. It would prove an ideal backdrop to epochal events.

Central High School

Five thousand people—presumably a very different five thousand from those who’d gathered around the trolley tracks at Ninth and Broadway a few months earlier—attended the dedication. The day’s speeches abounded with those superlatives Americans so love: the biggest this, the most expensive that. One even graced the new letterhead: “The most beautiful high school in America.” Another could have said: “the most archetypal.” Could there ever have been a high school that looked, well, so much like a high school? Most striking were the four stone sentinels above its monumental entryway, each symbolizing one of the values to be imparted inside: “Ambition,” “Personality,” “Opportunity,” and “Preparation.” Another of Central’s tenets went unrepresented, though it, too, could have been depicted in stone, perhaps by a figure with its hands held up, palms out: “Exclusion.” Little Rock’s new high school was, naturally, for whites only. Built like a fortress, for the next three decades it proved impregnable to Little Rock’s black children. For them, its manicured grounds might just as well have been a moat.

When Central was built, blacks in Little Rock had their own primitive, ramshackle school; another few years would pass before Dunbar High School—largely funded, as were thousands of schools for blacks throughout the South, by the Jewish philanthropist Julius Rosenwald—would open. It was designed by the same local architects who’d done Central, and, standing only a few blocks away, was modeled consciously, almost poignantly, after it. Not surprisingly, it was far smaller and less sumptuous, with fewer classes to take, fewer frogs to dissect, fewer fields to play on. Its textbooks were hand-me-downs from Central, bequeathed after many years’ use, sometimes arriving—the white students knew where they were destined—with racial epithets on their pages. But Dunbar, too, was considered the best of its kind, “the most modern and complete public high school building in the United States erected specifically for Negroes,” as a Works Progress Administration guide put it. “The dream of the colored people of Little Rock has come true … far beyond in beauty, modernity and size what the boldest had ever hoped for,” the local black paper declared when it opened.

Of all the states in the Old Confederacy, Arkansas was probably, on racial matters, the most enlightened. In the ferment following World War II, several graduate departments of the University of Arkansas admitted black students; when Silas Hunt entered its law school in 1948, he was said to have been the first black student at any state university in the Old Confederacy since Reconstruction. A handful of smaller towns peacefully integrated their schools following the Brown decision; Fayetteville so decided within a week of the ruling. (It was part the relative open-mindedness of a college town, part economic necessity: without a black high school of its own, the cash-strapped city had spent five thousand dollars the previous year to put up the nine black students it shipped off to segregated schools in Fort Smith and Hot Springs, fifty and two hundred miles away.) Faubus had been elected governor in 1954 as a racial moderate, someone who idolized Lincoln and, he liked to boast, would have backed the Union during the Civil War.2 Little Rock, population 100,000 at the time, was one of the most progressive cities in the region. Things had settled down since the lynching, in part because blacks had resumed their traditional places. “Accustomed since birth to characteristically Southern environmental factors, the Negroes of Little Rock and North Little Rock accept them with little outward evidence of resentment,” stated a WPA report from 1941.3

By the mid-1950s, though, blacks could use some parks and, on certain days, the zoo; some of the “whites only” and “colored” signs had been removed from drinking fountains. Thanks to court cases and protests, black schoolteachers earned as much as whites; black policemen patrolled 9th Street.4 In 1954, the year before Martin Luther King, Jr., led his famous boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, Little Rock quietly desegregated its buses. So when Elizabeth’s mother set off to clean the houses of wealthy white families in Pulaski Heights, she could sit wherever she pleased. The handful of white professors at the local black college, Philander Smith, could eat at the “strictly colored” Charmaine Hotel without being prosecuted, as they would have been in Mississippi. Little Rock boosters noted with pride that white salesmen now waited on black women when they bought shoes. Even the conservative Arkansas Democrat had come to use “Miss” and “Mrs.” when writing about black women.5 With his “Land of Lincoln” Illinois license plates, the NBC newsman Sandor Vanocur was terrified to enter places like Jackson, Mississippi, or Birmingham, Alabama, but in Little Rock he felt just fine.

But beneath this comparatively tolerant façade, Jim Crow was alive and well in Little Rock. Newspaper policy notwithstanding, whites invariably called blacks by their first names. The train and bus stations still had separate waiting rooms, though more now by custom or habit than by stricture, integrated whenever some oblivious outsider stumbled into the forbidden realm. “Sometimes a white person drinks from the ‘wrong’ fountain, discovers his mistake and ambles away with a sheepish grin,” one reporter noted. Blacks could not patronize local soda fountains and coffee shops, or the restaurants in the downtown department stores; the first lady of the black press, Ethel Payne of the Chicago Defender, couldn’t find a place to eat, at least in the white part of town, while seated; like other blacks, she had to order her victuals through the back door. (To Payne, who’d traveled all over the segregated South, Little Rock was “the crummiest corner on the map.”) Harold Isaacs of MIT, who came to study race relations in Little Rock in November 1957, learned that there wasn’t a single establishment where he could have a cup of coffee with a black man. Were a white man to sit with a black woman in one of the colored establishments on 9th Street, he was told, there would inevitably be trouble, requiring police intervention.6 No hotel would accommodate Carl Rowan, then a young reporter for the Minneapolis Tribune. Daisy Bates, who besides running the Arkansas NAACP copublished (with her husband, L. C. Bates) the weekly black newspaper the State Press, effectively turned her home into a rooming house for visiting black reporters. (Their paper barely scraped by, threatened by both black penury [and timidity] and fickle white patronage. “Can you vision [sic] what it takes to build up a newspaper in the deep south, contrary to the white man’s wishes and way of thinking among a bunch of ‘Uncle Toms’ who do not even know that the Emancipation Proclamation has been signed?” L. C. Bates once wrote to an impatient black creditor.) For all the rules, written and unwritten, guiding relations between the races, there were dangerous areas of gray. As one local black lawyer, Robert Booker, told Isaacs, sometimes one was lured into them by an ostensibly friendly gesture.7

Even in her insular and constricted world, Elizabeth had had brushes with southern racial reality. To get ice cream—and eat it before it melted—she and her family had to go to the colored waiting room of the Little Rock train station. Though the main library was officially integrated, blacks had to read the books somewhere else. She could watch movies only in the (segregated) Gem Theater or, as in the Lee, from the balconies of a few white theaters. The one time Elizabeth prepared to sit down and eat with the family for whom she did occasional housework, the mother—a Girl Scout troop leader—had quickly found something else for her to do. For a white neighbor, Elizabeth waxed the floors the woman’s own daughters refused to do. As payment, she was given two old hand-me-down skirts.

Because the Eckfords traveled little, Elizabeth had been spared the segregated (or nonexistent) restrooms, restaurants, and hotels she would have encountered on the road. But she came instinctively to recognize the invisible borders of Jim Crow culture. She noticed that white and black children played together easily until around age ten, when the word “nigger” crept into the white kids’ vocabularies. She learned that white people were to be feared: they could hurt you and your parents, without cause or cost. She saw that white children were more spontaneous and uninhibited than black children, perhaps because they didn’t fear the white man’s wrath. She noticed, too, that black children from the North felt freer than children like her. That became painfully apparent with the notorious case of Emmett Till, the young black boy from Chicago who’d been murdered in Mississippi in 1954 after supposedly whistling at a white woman; Till had been barely a year older than Elizabeth. She remembered seeing the famous picture of him in his casket, his body beaten and bloated, that appeared in Ebony. But that was Mississippi, and Mississippi, she believed, was a different world from Arkansas.