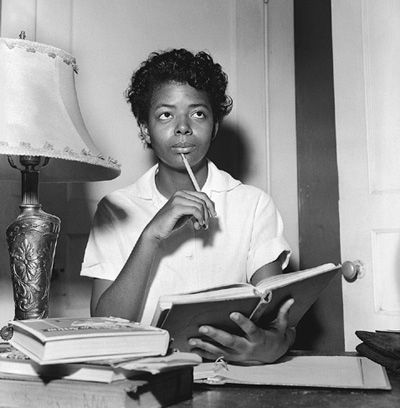

Officially, the NAACP discouraged what its executive secretary, Roy Wilkins, called “sideshows and exhibitions” involving Elizabeth or the other black students. Their education—that is, once it resumed—was to come first. But Elizabeth was produced to selected reporters, who made their way to the Eckford home, which they tended to describe as some variant of “—— but ——.” (Ted Poston’s “spic-and-span but much used” was typical.) She knew that going to Central wouldn’t be easy, Elizabeth told Walter Lister of the New York Herald Tribune, but her pastor had urged her once to take advantage of every opportunity. “I believe in being independent,” she said. “I don’t like to wait for somebody else.” A picture of her, book in hand and pencil at the ready, appeared alongside the story on the front page. “It helps to know we have such support,” Elizabeth—“her lips in a trembling smile”—told Virginia Gardner of the Daily Worker. Elizabeth was slighter than Gardner had anticipated, and her hands felt tiny. “She was terribly upset for a while, but she is pulling out of it,” her step-grandmother told Gardner.1

Al Nall of the New York Amsterdam News asked the “cute little lass” what people had shouted at her. “I wouldn’t want to repeat those words,” Elizabeth replied. “Some of them I never heard before, but I don’t like them.”2 So in awe of Elizabeth was Moses Newson of the Afro-American that sometimes he stopped taking notes while interviewing her, the better to contemplate her courage. (Her voice quiet and muffled, Elizabeth often had to repeat what she’d just said; to spare herself that, she cultivated a precise, articulate speaking style she was never to lose.) “Elizabeth Ann Eckford, 15, is the most sensitive of the children,” a New York Post reporter wrote. “She’s pensive, the kind of person who loves deeply and can be hurt deeply.”

Elizabeth studying at home, September 1957 (Bettmann/Corbis)

Elizabeth quickly wearied of all these reporters, however sympathetic they might be. “I wish they could get together and have one press conference and get it over with,” she complained. The others in the Nine teased her that she should charge for interviews. Seeking to protect her, Daisy Bates told the press that she had sent Elizabeth out of town for the weekend, and rumors flew that the girl had gone to San Francisco for a speaking engagement. The St. Louis Argus reported “particular spirited bidding” for such appearances. But of course, that was quite impossible; even now, Birdie Eckford would have never let her leave home.

Virginia Gardner asked Birdie how she had prepared Elizabeth for desegregation, only to realize “that that is what Negro mothers in the South have been doing for generations.” To the Associated Press, Elizabeth’s mother was calm, and sanguine. Did she believe school integration would lead to socially awkward situations? “See that vacant lot across the street?” she replied. “Negro and white children play ball there and they get along fine.” Long-distance telephone calls for Elizabeth came into her grandfather’s store from Chicago, Detroit, New York, even Oklahoma. Though all of the Nine got letters, usually sent via Daisy Bates, Elizabeth got far and away the most, as many as fifty a day. Things got so lopsided that Bates—who’d publicly called Elizabeth the “star of the show”—privately urged NAACP branch presidents to send messages to the other eight. When the Today show devoted a program to the events in Little Rock, it felt compelled to ask for anyone but Elizabeth.

One letter, from a sixteen-year-old in Japan, was addressed simply to “Miss Elizabeth Eckford, Littol Rocke, USA.” Another, from New Zealand, arrived with just her name and the picture. So much mail came from Germany that a schoolmate of German descent was recruited to translate it for her. (Elizabeth, characteristically, hoped for letters from France, so that she could work on her French.) An Englishman living in Zurich sent her a hundred dollars. She saved everything she received, putting it all in a cardboard box. Only from Arkansas was there was no mail: detractors would have been too ashamed, and supporters perhaps too fearful. But a few sympathetic whites left cash for her at her grandfather’s store. And on her sixteenth birthday in early October, a white man whose name Elizabeth never learned stopped by her home with a Girard-Perregaux watch belonging to his dying wife. (Elizabeth used it for many years.) Not every gesture was so positive: someone threw a brick through the window of Eckford’s Confectionary, and the filling station where her father bought gas for his truck cut off his credit.

Faubus, too, received an enormous amount of mail. Many of his correspondents praised him, but several who didn’t enclosed the picture of Elizabeth for emphasis. “It is with real shock that I see the face of an otherwise beautiful girl distorted by arrogant hatred as in the inclosed [sic] picture. The serene dignity displayed by the negro girl whom the white girl is jeering is mute evidence of where real Christian virtue and superiority reside,” stated Josephine Gomon of Detroit. “What ugly white women you have in Little Rock,” Adelaide Forbush wrote from Los Angeles. “The Negro girl shows much more dignity and courage.” Penny Rover of Chicago proposed a monument in Elizabeth’s honor. Several cited Scripture. “I also saw the picture of the colored girl leaving the school—by order of the Guard—walking alone,” went one. “Reminded me of the picture of Christ—he, too, walked alone on his trip to Gethsemane.” “IT IS A SAD COMMENTARY FOR THE LEADERSHIP OF ARKANSAS WHEN A 14 YEAR OLD NEGRO CHILD HAS MORE DIGNITY AND COURAGE THAN THE GOVERNOR OF ARKANSAS,” wired a man named Raymond Burks.

Because she’d rarely been identified by name, Hazel got little mail. A few letters—all from the North, all critical—were sent to her care of Central. One simply had the picture pasted to the envelope. “To this girl,” it was addressed. Hazel read them, found their critical tone surprising, then gave them little mind.

Some criticism went directly to the newspapers:

Miss Hazel Bryan:

I have often been told by my friends that I am the world’s worst correspondent, but to you I will take the time to write this letter. I have just read the paper in which your name was mentioned, as having acted as a leader in persecuting a colored girl (not nigger) in connection with this mess you have down there.

I can only say that you are a disgrace to the female sex, a terrible American and, I am sure, a sore disappointment to God.

Maybe when you grow up, if you ever do, you will be ashamed of yourself. I hope so for your sake. I could say much more, but I won’t bother.

A Disgusted Reader of the Milwaukee Journal

P.S. I am white.

Anyone favoring what Hazel had done was probably disinclined to say so. But in one letter to the governor, Hazel came in for a bit of sympathy. “One feels compassion for the white children who have been handicapped with hatred by alleged adults,” wrote Lucille Toll of Long Beach, California.

Around Hazel’s church there was embarrassment over the photograph but little surprise: Hazel, they knew, didn’t do anything halfway. But at Central, there were repercussions. Mrs. Huckaby didn’t recognize the screaming girl in the picture at first, nor did any other school officials. “Small wonder,” she later wrote. “We weren’t used to seeing our pupils like that.” But she soon realized it was Hazel Bryan, that girl who had tried to poison herself a few months earlier. She promptly hauled Hazel into her office. Hazel hadn’t a clue why; she thought that maybe it was to hand over some more letters.

“I told her that I was distressed at the picture because hatred was a feeling that destroyed the people that hated,” Mrs. Huckaby later wrote. “She shrugged. Well, that was the way she felt, she said. I hoped, anyway, that I would never see her pretty face so distorted again. I certainly hadn’t recognized that that ugly face was hers. More breath wasted.” Sure enough, the following Monday Hazel was at it again, telling the Democrat—in a line cribbed from her preacher—that had God meant for whites and blacks to mix, he’d have made them the same color. “The boys and girls pictured in the newspapers are hardly typical and certainly not our leading students,” Mrs. Huckaby wrote her brother in New York. “The girl (with mouth open) behind the Negro girl is a badly disorganized child, with violence accepted in the home, and with a poor emotional history.” She returned to Hazel in a postscript. “Don’t think I haven’t reprimanded this child!” she added.

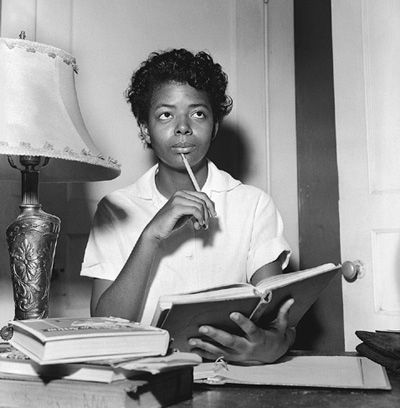

Mrs. Elizabeth Huckaby (Central High School Pix, 1958)

Hazel’s parents found her sudden notoriety sufficiently alarming to pull her out of Central: whatever educational advantages it offered paled next to concerns for her safety. Only recently having been so intent upon keeping Elizabeth out of Central, Hazel soon ceased to be a part of Central herself. For a few days she attended a small high school near Redfield. But staying there meant living with her grandparents, who were poor and had neither a car nor indoor plumbing. For Hazel, accustomed to a doting father and the creature comforts of home, that wouldn’t do. So she quickly transferred to Fuller High School in rural Sweet Home, on Little Rock’s outskirts, which was actually closer to her house than Central had been. As linked as she became to the Little Rock Nine, then, Hazel Bryan did not in fact spend a single day inside Central with any of them.

The decision to move Hazel did protect her from a great menace: herself. Had she remained at Central, she would surely have joined in the despicable deeds to come. Instead, she returned to pursuits that mattered far more to her than race relations. While registering at Fuller, she spotted a handsome, dark-haired boy named Antoine Massery. “That one’s mine,” she told her sister, who had transferred with her. And before long, he was. Hazel traded in the airman’s ring for a stereo.

America had seen its last of Hazel for the next forty years—except, that is, for the Hazel of the picture, which appeared with ever-increasing frequency as the Little Rock story evolved from current events to old news to history. In 1960 the picture graced the cover of its first textbook, a collection of materials on the schools crisis. With each iteration, her image increasingly became the official face of intolerance.